by Deep Green Resistance News Service | Dec 26, 2017 | Colonialism & Conquest

Featured image: The Guarani continue fighting for their land rights despite continuous attacks. © Fiona Watson/Survival International

by Survival International

Ten years ago the Brazilian government signed a landmark agreement with the Guarani tribe, which obliged it to identify all their ancestral lands.

The core objective of the agreement, which was drawn up by the public prosecutors office, was to speed up the recognition of the Guarani’s land rights in the southern state of Mato Grosso do Sul.

However, one decade on, most surveys have not even been carried out and the authorities’ failure to recognize the Guarani’s land rights continues to have a terrible impact on the tribe’s health and well-being.

With no immediate hope of recovering their land and rebuilding their livelihoods, thousands of Guarani are trapped in overcrowded reservations where the prosecutors say there is so little land that “social economic and cultural life is impossible.”

Other Guarani communities live along busy highways or on fragments of their ancestral land, hemmed in by vast sugar cane and soya plantations. They cannot plant, fish or hunt and have no access to clean water.

A Guarani-Kaiowa couple sit outside their makeshift roadside settlement of the Apy Ka’y community, near Dourados, Mato Grosso do Sul, Brazil. © Paul Patrick Borhaug/Survival

Health workers report that these communities are suffering from severe side effects of pesticides used by agribusiness. Some communities say their water resources and houses are deliberately sprayed by the ranchers.

A recent study estimated that 3% of the indigenous population in the state could be poisoned by pesticides, some of which are banned in the EU.

Malnutrition especially among babies and young children is common. According to Gilmar Guarani: “Children cry and cannot put up with this situation any more. They are really suffering and are very weak. They are practically eating earth. It’s desperate.”

Mato Grosso do Sul is home to the second largest indigenous population in Brazil, with 70,000 Indians belonging to seven tribes.

Much of their ancestral land has been stolen from them by cattle ranchers and agribusiness, and now they occupy a mere 0.2 % of the state.

John Nara Gomes says: “Today the life of a cow is worth more than that of an indigenous child… The cows are well fed and the children are starving. Before we were free to hunt, fish and gather fruits. Today we are shot by gunmen.”

The despair among the Guarani at the loss of their lands and self sufficient life is reflected in extremely high rates of suicide . In the period 2000-2015 there were 752 suicides. Statistics collected since 1996 reveal a rate that is 21 times greater than the national one. This is probably under-estimated as many suicides are not reported.

Damiana Cavanha, leader of the Apy Ka’y community, has seen the deaths of three of her children and her husband. She is determinedly planning a reoccupation of their ancestral land where they are buried. © Paul Patrick Borhaug/Survival

The Guarani also face high levels of violence and are constantly targeted by ranchers’ gunmen whenever they attempt to take back parts of their ancestral land. Recent data shows that 60% of all the assassinations of indigenous people in Brazil occurred in Mato Grosso do Sul state.

With a government and congress dominated by the powerful agribusiness sector, the landowners in Mato Grosso do Sul will not cede an inch. Many have resorted to the courts as a delaying tactic, to challenge the identification of Guarani territories. One core Guarani territory has had 57 legal challenges.

Despite this bleak scenario many Guarani vow to fight on: “Brazil was always our land. The hope that feeds me is that our land will be recognized, for without it we cannot care for nature and feed ourselves. We shall fight and die for it” says Geniana Barbosa, a young Guarani woman.

by Deep Green Resistance News Service | Dec 24, 2017 | The Problem: Civilization

by Derrick Jensen

When I’m on the road, I always carry a baseball bat in the back of my truck to use each time I see a snake. If the snake is sunning herself, I stop the truck and use the bat to shoo her to safety. Sometimes, if the snake is especially sluggish, I loop her over the bat and carry her out of traffic. If she’s already dead I don’t use the bat at all, but carry her to my truck, then take her to some quiet spot where she can lie to decompose with dignity.

But most often when I stop I have to use the bat not to save the snake but kill her. Too many times I’ve seen them live and writhing with broken backs, flattened vertebrae, even crushed heads.

I hate cars, and what they do. I do not so much mind killing, if there is a purpose; if, for example, I’m going to eat what I kill. But I despise this incidental killing that comes each time a soft and living body happens to be in our way. Such a killing is without purpose, and often even without awareness. I have driven through swarms of mating mayflies, and have seen a windshield turn red blotch by blotch as it strikes engorged mosquitos. I once saw a migration of salamanders destroyed by heavy traffic in a late evening rain. I leapt from my car and ran to carry as many as I could from one side of the road to the other, but for every one I grabbed there were fifty who made it not much further than the first white line.

A couple of years ago someone dropped off a huge white rabbit near my home. Knowing the cruelty of abandoning pets into the wild and the stupidity of introducing exotics did not lessen my enjoyment of watching him cavort with the local cottontails a third his size. But I often worried. If at one hundred yards I could easily pick him out from among the jumbled rocks that were his home, how much more easily would he be seen by coyotes or hawks? Each time I saw him I was surprised anew at his capacity to live in the wild.

I needn’t have worried about predators. One day I walked to get my mail, and saw him dead and stiff in the center of the road. I was saddened, and as I carried him away to where he could at last be eaten by coyotes, I considered my shock of recognition at his death. I had, as I believe happens constantly in our culture–in our time of the final grinding away at what shreds of ecological integrity still remain intact–been fearing precisely the wrong thing. I had been fearing a natural death. But in one way or another, most of us living today–human and nonhuman alike–will not die the natural death that has been the birthright of every being since life began. Instead we will find ourselves struck down–like the rabbit, like the snakes, like the cat whose skull I had to crush after his spine was severed by the shiny fender of a speeding car–incidental victims of the modern, industrial, mechanical economy. This is no less true for the starving billions of humans than it is for the salmon incidentally ground up in the turbines of dams, and no less true for those who die of chemically-induced cancers than it is for the mayflies I killed by the thousands, blithely driving from one place to another.

All of us today stand as if transfixed by the headlights of the hurtling machine that inevitably will destroy us and all others in its path. Oh, we move slightly to the left or slightly to the right, but I think, as I carefully place the rabbit in a tufted hollow at the base of a tree, that even to the last, most of us have no idea what it is that’s killing us.

Originally published in the September/October 1998 issue of “The Road-RIPorter.” Republished in the January-March 2007 issue of “Carbusters.”

by Deep Green Resistance News Service | Dec 23, 2017 | Lobbying

Private landowner on Kaua’i legally recognizes nature’s rights

by Community Environmental Legal Defense Fund

HAWAII: For the first time, ecosystems and natural communities on eight acres of land on the island of Kaua’i possess legal rights to exist, thrive, regenerate, and evolve. This is the first Rights of Nature conservation easement on the Hawaiian Islands.

The effects of pollution and climate change wrought by corporate practices are devastating habitats and destabilizing communities on Hawaii and other Pacific islands. For many residents, waiting for government to protect them is no longer an option.

“Rights of Nature is already in the air, the sea, and the people of Hawaii, so recognizing legal Rights of Nature on land that is in my name came quite easily for me,” explained Joan Porter, the Kaua’i landowner who recognized nature’s rights through the conservation easement. “I established the easement in hopes that other landowners and governments will also understand the need to change the status of nature from property to bearing rights.”

The Community Environmental Legal Defense Fund (CELDF) has pioneered the Rights of Nature movement in the U.S. and globally. The Rights of Nature conservation easements are a growing part of that movement.

CELDF assisted Porter in the drafting of the easement, making Kaua’i the second locality where a private landowner in the U.S. changed the status of nature through an easement to recognize the rights of ecosystems and natural communities in perpetuity. The Kaua’i easement contains provisions on climate change, genetic engineering, restriction of corporate rights, and enforcement language.

A key partner in the Rights of Nature work in Hawaii has been the Kaua’i-based organization Coherence Lab. Prajna Horn, co-founder and executive director, stated, “There is a fundamental shift happening across our planet today, where more people are beginning to understand Indigenous wisdom and the inseparable relationship between humans and the Earth. Rights of Nature is rooted in Indigenous wisdom and is based on aligning with Natural Law. Thus, the legalization of the Rights of Nature is really about a remembering of how to live a harmonious, balanced and respectful life for the sake future generations. I’ve been engaged in the Rights of Nature movement for close to a decade. Through this conservation easement and other Rights of Nature work, I am grateful to have had the chance to bring CELDF to Kaua’i.”

For over a decade, CELDF has been assisting communities, countries, and tribal nations to transform the legal status of nature. In 2006, Tamaqua Borough, Pennsylvania, became the first government in the world to legally recognize nature’s rights. Since then, more than three dozen communities in more than 10 states in the U.S. have secured nature’s rights. In 2008, CELDF assisted Ecuador to draft constitutional provisions recognizing the Rights of Nature. The new constitution was overwhelmingly adopted by citizens. Most recently, the General Council of the Ho-Chunk Nation in Wisconsin approved an amendment to their tribal constitution to recognize the Rights of Nature.

As the Rights of Nature builds momentum, in the past year, courts in India and Colombia have issued decisions recognizing the rights of rivers and glaciers. In its decision securing rights of the Atrato River, the Colombia Constitutional Court wrote:

“…[H]uman populations are those that are interdependent on the natural world – not the other way around – and…they must assume the consequences of their actions and omissions in relation to nature. It’s about understanding this new socio-political reality with the aim of achieving a respectful transformation with the natural world and its environment, just as has happened before with civil and political rights…economic, social and cultural rights…and environmental rights.”

“The Rights of Nature easement is a bold first step in a broader legal and cultural paradigm shift,” says Kai Huschke, Northwest and Hawaii organizer for CELDF. “For generations, the people and ecosystems of Hawaii have endured ‘legalized’ colonization, toxic pollutants, and GMOs. People are saying ‘Enough!’ Many residents in Hawaii – and around the world – are moving towards law being used to protect the rights of coral reefs or the rights of tropical forests, rather than law being used to destroy them.”

The Community Environmental Legal Defense Fund is a non-profit, public interest law firm providing free and affordable legal services to communities facing threats to their local environment, local agriculture, local economy, and quality of life. Its mission is to build sustainable communities by assisting people to assert their right to local self-government and the Rights of Nature. www.celdf.org.

by Deep Green Resistance News Service | Dec 20, 2017 | Strategy & Analysis

by Max Wilbert / Deep Green Resistance

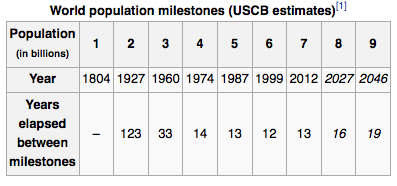

According to an article in the Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences in July, the planet is in the midst of the 6th mass extinction event. Strikingly, the scientists who wrote the article call this a “biological annihilation.”

This isn’t a random sequence outcome of a natural societal development. The dominant global culture (industrial civilization) is a culture of imperialism. We can define that as a culture that colonizes and extracts resources as a standard way of operating.

Industrial civilization has become the dominant culture by violence, and violence maintains it.

Timber is ripped from forests and shredded for sale. Rivers are enslaved to irrigate fields and power cities. Oil is burned to propel commerce. Fracking injects poisons into the planet in order to extract even more petrochemicals. Traditional ways of life and sustainable relationships with the land are destroyed, so the only alternative is the toxic (and profitable) cycle of wage labor, debt, and poverty. Patriarchy teaches men to objectify and dominate women, and women to acquiesce. The result is a loss of bodily autonomy to the point that half of all children are unwanted by the mother, and a culture in which eating disorders are a leading cause of death among young women and teenage girls. The legacy of slavery underlies the modern prison system, where vast profits are made by locking up the powerless and oppressed.

As a friend put it, “oppression is always in service of resource extraction.”

The shiny gadgets used to enthrall us are made possible by child miners in the Congo, by workers toiling to the point of mass suicide in Foxconn factories in China, and by the exportation of e-waste to conveniently isolated locations.

And of course, the military, police, and private security (mercenaries) are ready to beat, imprison, or kill anyone who stands in the way of this system. Finally, this culture’s atomized families and recent trends like the rise of neo-liberalism help ensure we remain isolated physically and emotionally, without the strength that comes from being part of a community.

Between the threat of violence, bribery, and the sense of helplessness that comes from isolation, most people aren’t willing to resist. American culture has been built on genocide for 500 years; at this point, most settlers can’t even imagine a society not based on violence.

For those who can, we need to get serious about our strategies.

MYTHICAL STRATEGIES

In the west, and especially in the United States, most activists operate within a mythic framework of non-violent resistance that’s far different than the liberation politics of the 1960’s and 70’s. In this mythology, violence doesn’t solve anything, and non-violence has a magical ability to win conflicts—even if those victories only occur in hearts and minds.

“We win through losing,” a friend says (sarcastically) of this mindset.

Don’t get me wrong. Non-violence can be a supremely elegant and effective technique for social change. Applied correctly—forcefully—non-violence can immobilize a repressive regime or corporate power, making it impossible to move in any direction. Violence should, of course, be avoided anytime it can be.

But non-violent resistance doesn’t always work. As another friend writes in his excellent multi-part series, “The destruction of our world isn’t an ‘environmental crisis,’ nor a ‘climate crisis.’ It’s a war waged by industrial civilisaton and capitalism against life on earth–all life–and we need a resistance movement with that analysis to respond…the decision about what strategy and tactics to use depends on the circumstances, rather than being wedded to one approach out of a vague ethical dogma…the choice between using non-violence or force is a tactical decision. Those who advocate for the use of force are not arguing for blind unthinking violence, but against blind unthinking nonviolence.”

So what’s next? What happens when non-violence doesn’t work? What should you do when you have voted, petitioned, demanded, protested, raised awareness, locked down, blockaded, and it hasn’t worked?

Do you keep using the same tactics that have failed again and again, hoping they’ll work this time?

Do you give up?

This is not a theoretical question.

It’s a situation that has been faced by many resistance movements throughout history. Lately I’ve been reflecting on one in particular; the Oka Crisis that went down near Montreal in 1990.

After 400 years of gradual land theft, the Kahnesetake band of the Mohawk Nation was left with a fraction of a fraction of its traditional territory. With land “development” encroaching continuously, tensions came to a head in 1990 when plans began moving forward to expand a golf course into an extremely important site: a pine forest next to the tribal cemetery.

Members of the Kahnesetake community went through various channels to fight the expansion, including petitioning local government and the federal Indian Bureau. Nothing worked, so they began a non-violent occupation of the golf course. After a gradual escalation—police beatings, threats from masked assailants—many of the Mohawks began carrying weapons. Special police forces were called in to raid the camp, and women stood them down. Someone began shooting—from which side is impossible to say—and a policeman was killed. After a weeks-long standoff during which many more shots were exchanged, the Mohawks were eventually evicted—but the land was protected from development.

Are we committed to winning as much as those Mohawk warriors?

Species extinction, fascist and Nazi extremism, global warming, police violence, sexual assault, human trafficking, resource extraction, industrial expansion, the prison industrial system. Are we committed to stopping these injustices?

If so, we must consider all means, including the use of force and violence.

This is an emergency.

HOW A REVOLUTION MIGHT BEGIN: THE CUBAN PRECEDENT

Perhaps one of the more important lessons of revolutionary history comes from Cuba, where in 1956, a small group of revolutionaries landed near the Sierra Maestra mountains. Almost immediately, the rebels were attacked and routed. Of the original group of 80, only about 20 regrouped in the mountains.

Nonetheless, over the next several years, their movement grew. They recruited locals, coordinated with underground cells in Havana and other urban areas, and built support networks elsewhere in Latin America. By January 1959, the revolutionaries had overthrown the rule of the Batista government.

Marx informs any revolutionary, but I am not a Marxist. Like China and the Soviet Union, Cuba followed a highly centralized, industrialized development path that contains much to criticize (while still representing an inspiring alternative to the capitalist model). The events that took place after the Cuban revolution are, to me, less interesting than the methods used to carry out the revolution itself. Che’s guerilla warfare techniques were well suited to the rural countryside and have influenced every revolutionary group since. And there is much to learn from how the Cuban underground organized.

The most important lesson, I think, is that the revolutionaries just got started. They didn’t wait for the perfect conditions, which they knew would never appear. They suffered major setbacks, but they persisted, and they had unshakeable confidence that they would prevail. Despite their lack of numbers, they had a good foundational strategy. By playing to their strengths, avoiding unwise confrontations, and by gradually building strength, they defeated a force that was initially much superior and initiated a tectonic political shift from capitalist vassal state to socialist nation-building experiment.

DAKOTA ACCESS PIPELINE SABOTAGE

On July 24th, two women—Ruby Montoya and Jessica Reznicek—publicly admitted to sabotaging the Dakota Access Pipeline in an attempt to stop the desecration of native territory, the ongoing destruction of the climate, and threats to major rivers.

In an interview with them shortly after, they explained their motivations. Ruby, who was a kindergarten teacher before quitting her job to fight the pipeline, was in tears as she explained that those kids would have no future without action.

Jessica and Ruby have repeatedly called for others to take similar actions of eco-sabotage.

Last year, I published a call for ecological special forces:

“Small forces of ecological commandos that could target the fundamental sources of power that are destroying the planet. We have seen examples of this. In Nigeria, commando forces have been fighting a guerrilla war of sabotage against Shell Oil Corporation for decades. At times, they have reduced oil output by more than 60%.”

As we noted, “no environmental group has ever had that level of success. Not even close. In the U.S., clandestine ecological resistance has been relatively minimal. However, isolated incidents have taken place. A 2013 attack on an electrical station in central California inflicted millions of dollars in damage to difficult-to-replace components used simple hunting rifles. The action took a total of 19 minutes, displaying the sort of discipline, speed, and tactical acumen required for special forces operations.

“Our situation is desperate. Things continue to get worse. False solutions, greenwashing, corporate co-optation, and rollbacks of previous victories are relentless. Resistance communities are fractured, isolated, and disempowered. However, the centralized, industrialized, and computerized nature of global empire means that the system is vulnerable. Power is mostly concentrated and projected via a few systems that are vulnerable.

“Even powerful empires can be defeated. But those victories won’t happen if we engage on their terms. Ecological special forces provide a method and means for decisive operations that deal significant damage to the functioning of global capitalism and industrialism. With enough coordination, these sorts of attacks could deal death blows to entire industrial economies, and perhaps (with the help of aboveground movements, ecological limits, and so on) to industrialism as a whole.

“Implementation of this strategy will require highly motivated, dedicated, and skilled individuals. Serious consideration of security, anonymity, and tactics will be required. But this system was built by human beings; we can take it apart as well.”

That strategy, while not sufficient on its own, would help us move towards a more effective, forceful movement. Read that article here.

This may sound drastic to you. But consider: the planet is being destroyed. We’re living through the sixth great mass extinction event. The most powerful nation in the world just elected Donald Trump. There is no sign of a looming political shift, and alternative parties and movements are largely sidelined or co-opted.

CHARLOTTESVILLE COMES HOME

As I write this, I’m at my sister’s house; she’s just given birth to my (first) nephew, who has beautiful brown skin and is what’s called “mixed race.” Before long, he will emerge into the world, and he will be perceived as a black child, and then as he grows, a black man.

White supremacy is experiencing a resurgence. Days before I write this, at a neo-Nazi rally in Charlottesville, Virginia, hundreds of virulent racists marched, chanting “blood and soil” and “white lives matter.” In front of studiously inactive police, they severely injured more than two dozen anti-racist protestors and one fascist plowed his car into a crowd of anti-racist protestors, killing a woman and severely injuring others.

The day after, as my sister lay in bed nursing her new beautiful baby boy, more white supremacists were gathering in downtown Seattle, about two miles away. Later, the Amerikkkan president defended the supremacists, saying there were “great people” involved in the white supremacist protests.

To anyone who is paying attention, this isn’t a surprise. Our nation has been built on foundation of systematic white supremacy in service of the extraction of resources. Those are the roots of this society, and the trend continues today. The everyday violence of this culture fuels its operation. The system is functioning perfectly, exploiting every possible method for economic, social, and political gain while funneling wealth to the top.

How can I make a better world for my nephew? How can I make a survivable world? My answer—at least one part of it—is by halting that everyday violence.

It’s time that we organized and carried out a revolution.

—

Max Wilbert is a writer, activist, and organizer with the group Deep Green Resistance. He lives on occupied Kalapuya Territory in Oregon.

To repost this or other DGR original writings, please contact newsservice@deepgreenresistance.org