by Deep Green Resistance News Service | Apr 24, 2018 | Alienation & Mental Health

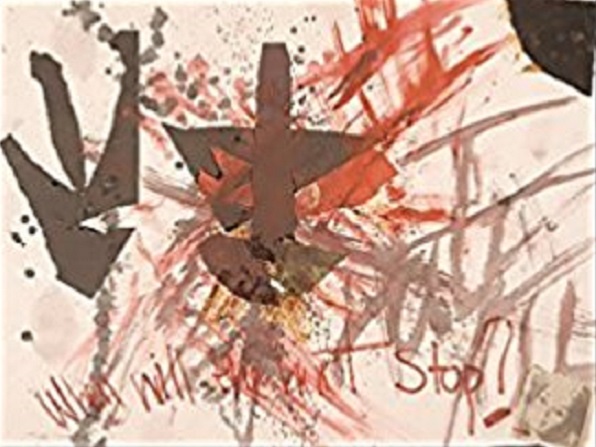

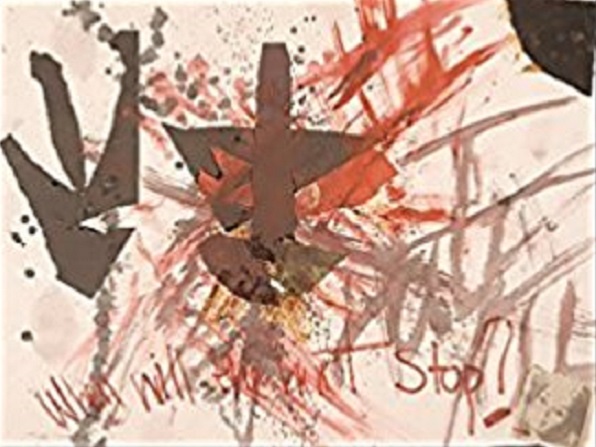

Featured image: Painting by Kaipo, age 4

by Boris Forkel / Deep Green Resistance Germany

Since the beginning of history, attempts have been made to develop power techniques with which our moral sensitivities can be undermined, so to speak, which activate less resistance in the people. These power techniques are now often referred to as soft power. Soft power is the full range of techniques to manipulate public opinion. Intermediaries for these forms of exercising power are supported by foundations, think tanks, elite networks and lobby groups — in particular private and public media, schools and the entire education and training sector as well as the cultural industry. The effects of soft power techniques are largely invisible to the public, so protests against these forms of indoctrination are unlikely. Economic reasons speak in favor of primarily using soft power and refining and optimizing these technologies for manipulation purposes on the basis of scientific research of our cognitive and affective characteristics. This has happened over the past hundred years in a very systematic and consequential manner.

—Rainer Mausfeld

Along with destroying livelihoods and community, one of the most important things our “culture” needs to do to function is the destruction of the self. Because if our very selfs wouldn’t have been destroyed, we wouldn’t put up with any of this shit. We wouldn’t go to work to sell eight hours or even more of our lifetime each day. We wouldn’t let our world be destroyed by rich, pathological, insane men. We wouldn’t inflict daily violence, even if oftentimes in a quite “soft” form, on our own children.

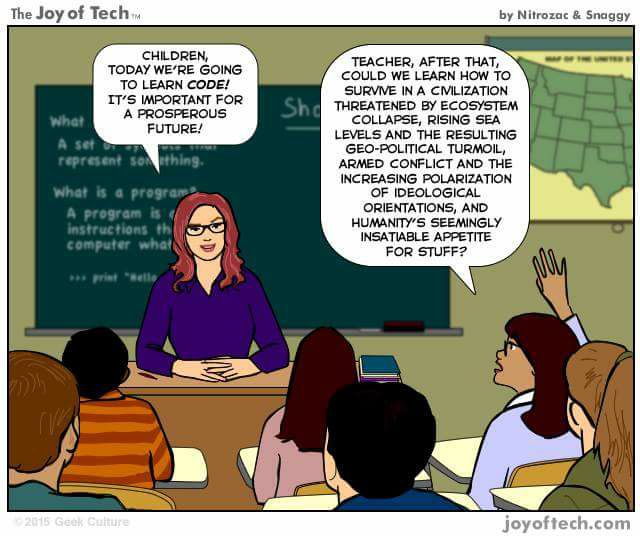

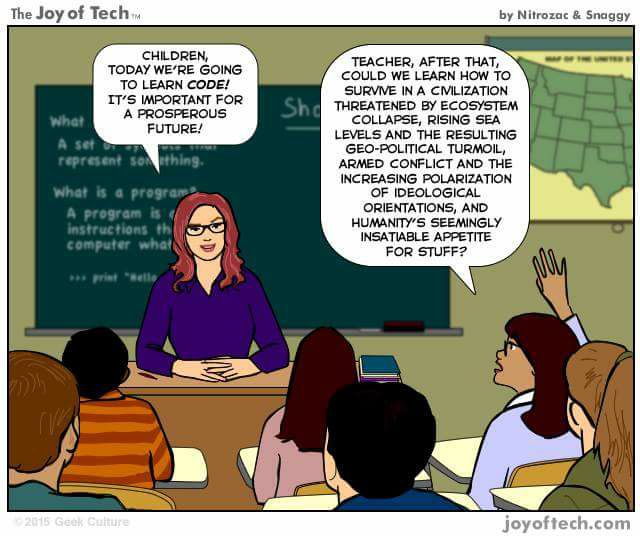

Of course, the destruction of the self is a very long and painful process, and therefore has to start at an early age. Rainer Mausfeld, professor of psychology and cognition research at the Kiel University, stated that the term competence (or skill) is one of the most ideological inflicted terms of our time. “The question those in power have been asking,” Mausfeld says, “is ‘how do we disassemble the self of the individual into a bundle of skills.’” He also states that “School is the most important soft-power instrument of the state.”

After all, what children learn in school are skills and competences; at the very best they would learn some form of social competence. What they don’t learn is to be a human being, to evolve, to think, to feel, to just be.

This concerns me a lot, because I’m the father of a little loving sunshine named Leonard, who will start attending school this summer.

When Leo started going to kindergarten, for me that started a process of remembering my own early childhood. I remembered how much I hated kindergarten as well as school, and it got me thinking about these forms of soft power.

Leo’s kindergarten is indeed a very good one. It is one of the famous German “forest kindergartens,” which means that the kids will be outside in the forest all day. Still, we had to go through what they call acclimatization phase, because a child of three has to be accustomed to being left alone by its parents. During the two weeks of this phase, one of us had to stay with our son at the kindergarten, leaving now and then for a while to get him used to being without us.

So often I have seen little children cry, when his or her mother would hand him or her over to one of the preschool teachers and leave. “Don’t go mom, don’t leave me!” the little ones would scream in sheer panic. “I’m so sorry my little darling, I have to go to work” was the usual answer.

I live in a pretty decent social environment. Most of the middle-class people here are kind and gentle; they love their kids and care for them. Some of them even told me that it breaks their heart to leave them. But they have been conditioned–like all of us–to believe that this is the way things are.

One time a child, whose mom had just left with the usual explanation, cried and just wouldn’t stop. Ian, who was at that time the oldest boy in kindergarten because he hasn’t been considered “ready” for school (seriously, who is?), commented with one of the smartest lines I’ve ever heard:

“We have to go to kindergarten because they have to go to work; If they don’t work, they won’t earn money; without money, they can’t buy groceries, and we’ll have to starve; starvation is worse than kindergarten.”

That morning I went home and cried. Seven year old Ian had just covered most of the internal violence of our culture in one sentence with a few semicolons.

Today, I had to wake Leo early at 6:00 in the morning, because I needed to bring him to his mom who would drive him to kindergarten. He hates to be woken up, as much as I did as a kid and still do. He was crying and resisting a lot. I hate it when I have to do this, because I know I’m inflicting a “soft” form of violence on him.

I love the quote by Smohalla, the Wanapum dreamer-prophet: “My young men shall never work, men who work cannot dream; and wisdom comes to us in dreams.”

I indeed believe that it is very unhealthy to be woken up early on a regular basis, because natural cycles of sleeping and dreaming are disturbed. That most of us have to get up early from an early age on, for kindergarten, school, work, is very bad for our mental health and therefore must be considered as part of the destruction of the self our “culture” is inflicting on us.

Usually, I wake him for kindergarten as late as possible. With everybody busy working, there is no community and no kids to play with in the neighborhood. This is the reason I want him to attend, because kindergarten is the only chance for him to regularly get in contact with other kids and gain some social competence.

We’ve had some meetings at the elementary school he’ll attend. I went there with him, and we stood with a bunch of kids from different kindergartens waiting for the teacher, with school kids playing around us. “Class 2b, to the classroom!” a teacher shouted. Immediately, about 25 children would run after her. It is amazing, I thought, how they are conditioned at a very young age to follow military-style orders.

Our teacher came and called us to follow her to the gym. At the door, she took Leo’s hand, smiled at me and said: “Daddy is going to wait outside.” While everybody else went in, I was the only one who had to stay in the cold schoolyard. After a short startling moment I understood. I’d been the only parent, while all others where preschool teachers.

The system needs to separate us very early, to destroy the strongest bonds of relationships, to make us weak and compliant. Of course, most of the teachers are nice and well-meaning people, at least at the elementary school near where I live. But they’ve gone through the very same process of conditioning. They learned that the most important thing is to follow orders. And that is what they do. Especially here in Germany, we should know that this in itself is very, very dangerous.

It terrifies me.

“Indian children are never alone. They are always surrounded by grandparents, uncles, cousins, relatives of all kinds, who fondle the kids, sing to them, tell them stories. If the parents go someplace, the kids go along,” said John (Fire) Lame Deer. Schools have been used in the US in a systematic and fierce way to destroy the kind of community Lame Deer describes. Of course, school has been much harder for them then it is for us civilized people. One reason for this is racism, another the systematic destruction of their native languages, that was largely done through school. But it is also because they just weren’t used to it. That time, they still knew how freedom and genuine community feels like. They still had something that we’ve lost long ago.

I’ve been asking myself why school is taking so long. I attended school for 12 painful years, and seriously, most of the time was wasted. Learning to read and write is not that hard; neither is learning some basic math. There are thousands of great books out there that cover much more than the things they teach you in school. Any average intelligent person could prepare for graduation in one or two years.

So, why all the wasted time?

Because the function of the school system is, first and foremost, to condition us with the experience that our lifetime doesn’t belong to us, but to a system. We have to be conditioned to sell eight hours or even more of our lifetime each day. We have to be conditioned, and broken, to identify with the company we work for instead of identifying with a community of family and friends, or even the land.

This is why they destroy all of it. The community, the land, and even the self.

Otherwise, we’d never put up with any of that shit. We’d resist, just like the American Indians did, until death.

by Deep Green Resistance News Service | Apr 8, 2018 | Alienation & Mental Health

by Boris Forkel / Deep Green Resistance Germany

The most basic commandment of our culture: Thou shalt pretend there is nothing wrong.

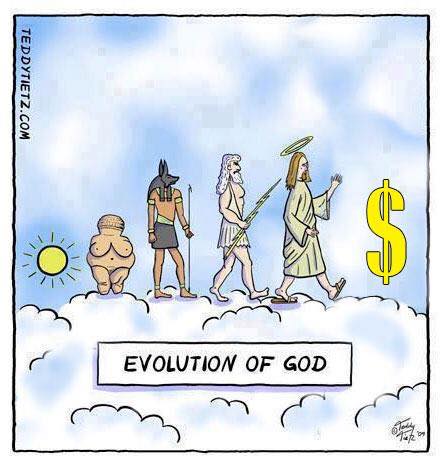

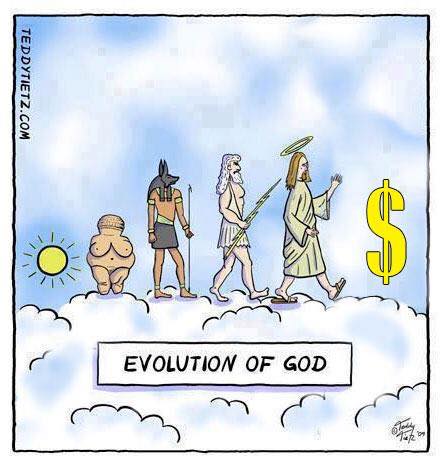

Indigenous cultures, uncivilized societies that did not build cities and lived as hunters and gatherers or from small scale subsistence farming, were land-based cultures. Their livelihoods were based on the land and the ecosystems.

Our culture–in the broadest sense civilization, in the narrower sense western, more recently industrial civilization–is based on faith. In terms of livelihoods, our culture is no longer based solely on the exploitation of its land base, but on the hyper-exploitation of almost all parts of the world, including the oceans.

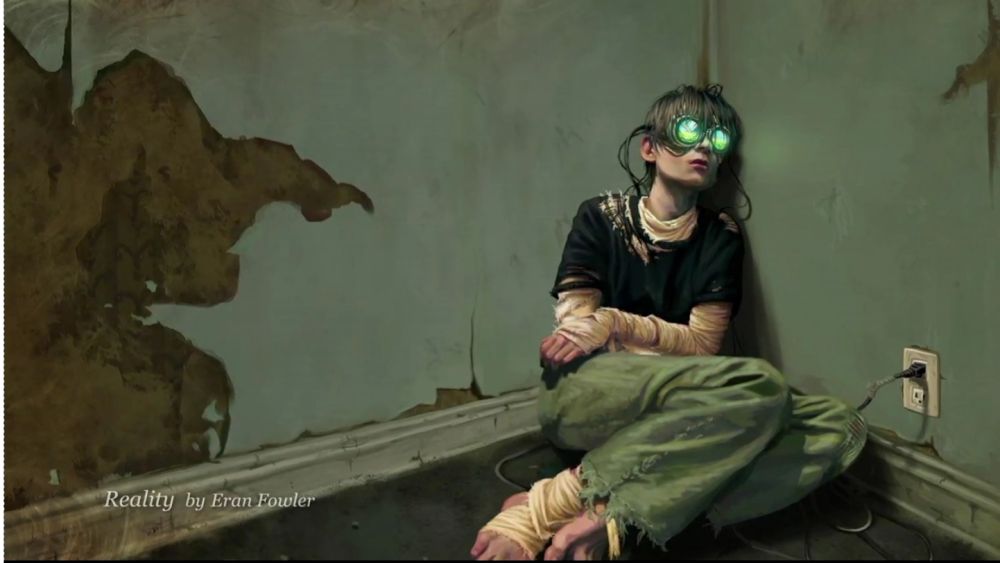

The people of our culture do not live in the real physical world. With their cities they have built their own world and with their beliefs their own artificial reality, with which they have largely sealed themselves off from the real world and the truth. Our culture is characterized by an increasingly complex technology. People are proud of it, identify with it and trust technology with an almost unshakable faith. Last but not least, they regard technology as synonymous with progress. Cultures without complex technology have for our culture about as much value as ecosystems. They are exploited, assimilated, “developed” and ultimately destroyed.

Our culture is based on faith, because only with strong belief systems coupled with the corresponding propaganda machinery can a potentially volatile mass like our modern society, with its unprecedented number of people, be managed, controlled and kept reasonably stable. Mass propaganda has always been of great importance for civilization. From the invention of writing to book printing, newspapers, mail, telegraphy, telephone, fax, radio, television and the internet; mobile phones and smartphones; to social media that gives us the illusion of contact with other people, while in reality we are sitting lonely in front of the screen of a machine. Technology is never neutral. Our form of technology is not so much a sign of a particularly advanced culture as a necessary instrument with which the rulers want to keep us under control. The current IT technology with its screen culture and digital hallucinations is the most effective opium for the masses ever invented, and at the same time the most perfect surveillance device of all time.

We have no culture and we have no society. Although I use these terms for lack of alternatives, our form of society is actually a kind of anti-culture that destroys any form of original culture and community. A culture would be a set of social rules, values and norms, aimed at organizing a stable and sustainable society. Essentially, culture regulates the relationship between human and non-human beings, i.e. the interaction with the land base as well as the relationships between humans themselves.

The current form, of liberalism, capitalism, consumerism, individualism, techno cult and popculture, neither knows rules for a meaningful interaction with the land base nor for the people between themselves. The only rule is the often unspoken, but very strong hierarchy with money as a synonym for power. Money has no value in itself. Yet for most people, money is like a religious fetish in which they believe and for which they do almost everything.

The beliefs of our culture have direct and profound effects on the real world and my own life. Why do you pay rent? I pay rent because I know that if I didn’t, ultimately the police would force me out of my apartment and I‘d be homeless. So I pay rent because I have to bow to structural violence. That the landlord owns my apartment and I have to pay for the right to live here is not based on any natural or physical laws, but is a purely social convention. It only works because the majority of the population believes in the right of the owners to exploit those who don’t own. De facto, I have to work for my landlord, for the only purpose of making him even richer than he already is.

Many of the beliefs on which our culture is based are not particularly credible in themselves and have a quasi-religious character, so the people of our culture must be indoctrinated from an early age. Without permanent indoctrination, our “culture” would immediately fall apart. That is why the rulers were so afraid of the ‚60s hippie culture and drugs such as cannabis and LSD: because they are able, in a sense, to resolve social conditioning. Obviously that wasn’t enough.

Our economic system is based on the belief in infinite growth on a finite planet. We act on the belief that we can make infinite use of finite fossil fuels. We believe that our transport system is more important than our breathing air, and we act as if a transport system based on fossil fuels and poisoning our air will last forever. We believe in infinite technological progress and consistently ignore the dramatic effects this belief has on the real world. We believe that we can destroy not only the climate and the oceans, but practically the whole planet and still live on it. We actually know better; yet we–or rather the rulers–act according to this faith. And we have been so polite and believe that the rulers have the right to diligently destroy our future and that of our children in order to increase their wealth.

Almost all the beliefs of our culture are bare lies that are not even particularly credible. Therefore, they must be constantly repeated through propaganda in order to permanently condition people. Out of these lies, the credulous people of our “culture” assemble their small, cozy, intact worlds, which they vehemently defend against the truth. Those who have a glimpse of the fact that not everything is all right will build even more defenses, choosing between New Age esoteric, the myth of the hundredth monkey, the hope of a collective paradigm shift, the belief in digital man as the consciousness of the universe, the golden age, etc., in order not to have to see the truth. Here too, the more absurd the faith, the more fervently it is believed and defended against all evidence.

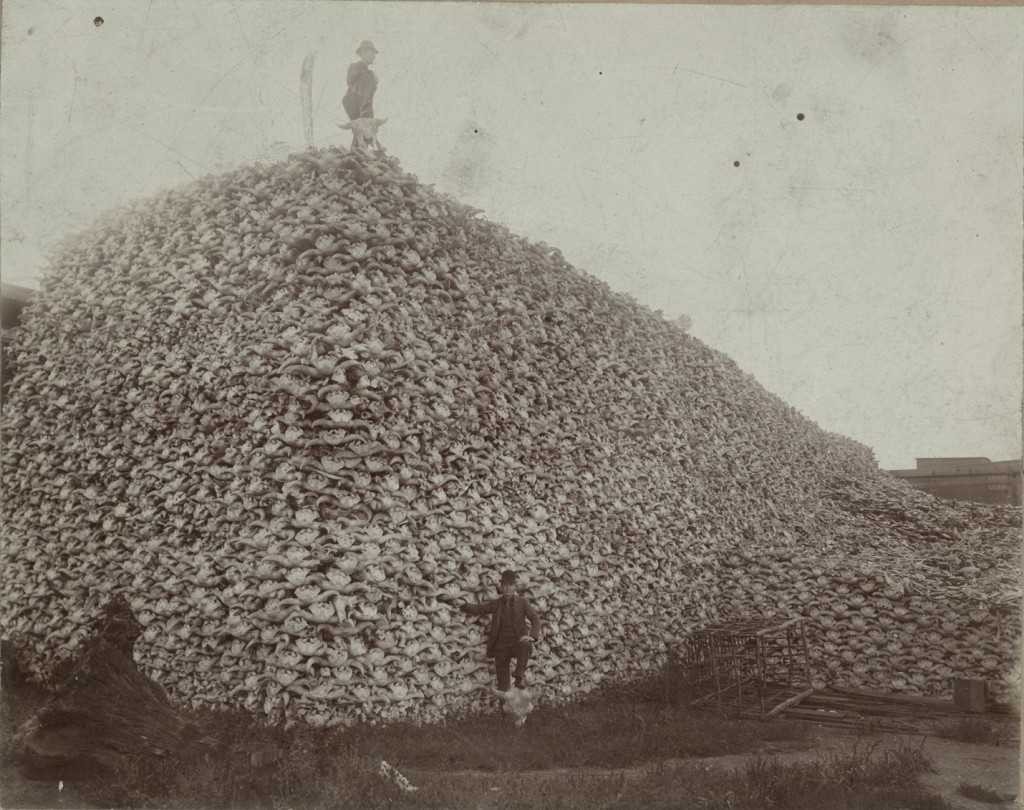

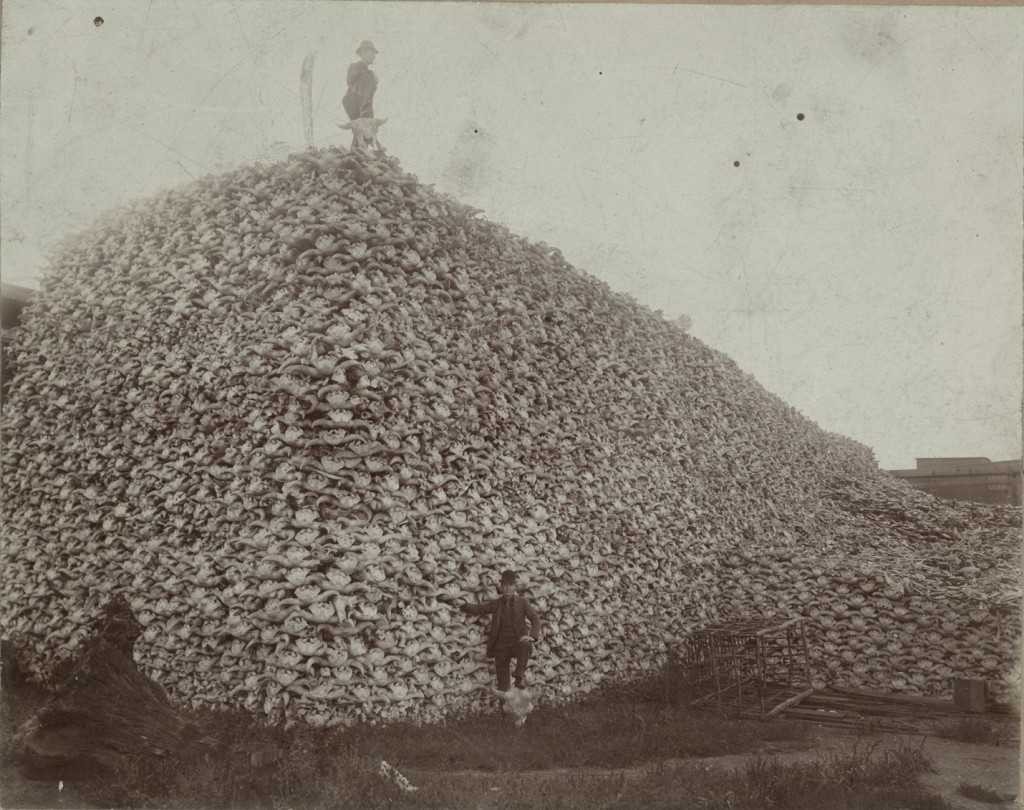

It is no exaggeration to state that this culture is pathologically insane. Our self-perception as “culture” is the self-perception of a madman. We believe that we are the most highly developed culture that ever existed, and that the cultures before us were primitive and regressive. Therefore, we also believe that it is justified to brutally eradicate “primitive” indigenous cultures all over the world. Progress has its price and you can’t make an omelet without breaking eggs. Racism, that is, the belief that a “race” of people (usually those with the lighter skin) are better, smarter, more progressive, stronger, higher developed than others–along with a distorted version of Darwin’s theory of evolution, the idea of the survival of the fittest, that applied to human societies forms the ideology of social Darwinism–has created a justification that has already proven itself in numerous genocides. Racism naturally refers to beings of other species (we do not use the term here, although it would be much more appropriate, since they actually are different races). My point is that indigenous people, just like wolves, bison, salmon, bears, lynxes, whales, gorillas and many other creatures, have been and continue to be victims of the Holocaust. And all this is based on the belief that we, as the crown of creation, have the right to eradicate all others and thus deny them the right to life.

“In order for us to maintain our way of living, we must, in a broad sense, tell lies to each other, and especially to ourselves. It is not necessary that the lies be particularly believable. The lies act as barriers to truth. These barriers to truth are necessary because without them many deplorable acts would become impossibilities. Truth must at all costs be avoided. When we do allow self-evident truths to percolate past our defenses and into our consciousness, they are treated like so many hand grenades rolling across the dance floor of an improbably macabre party. We try to stay out of harm’s way, afraid they will go off, shatter our delusions, and leave us exposed to what we have done to the world and ourselves, exposed as the hollow people we have become. And so we avoid these truths, these self-evident truths, and continue the dance of world destruction.”

Derrick Jensen, A Language Older Than Words

It is actually not difficult to see that our culture is based on violence and destroys all life on this planet. All we have to do is to take off the numerous cultural eyeglasses that guide our perception. Then we will lose faith in all these lies and realize the truth. This automatically puts us outside our culture and we cannot go back, because we have recognized it and all the lies for what they really are. Only from the outside do we see our civilization as the terrible monster that consumes and destroys all living things.

What remains is actually only the faith in Mother Earth and the land base on which you live. And that makes sense, because behind all of these collective hallucinations, it is still Mother Earth who keeps us alive. Nature has produced an incredible variety of creatures and continues to do so if we only let her. So it is the moral duty of every person who no longer identifies with this culture but with the real world, to defend life on the planet against the monster that is civilization.

by Deep Green Resistance News Service | Feb 15, 2018 | Alienation & Mental Health

Featured image: JD Lasica, Flickr, c.c. 2.0

by Steven Gorelick / Local Futures

Tucked within the pages of the January issue of the Agriview, a monthly farm publication published by the State of Vermont, was a short survey from the Department of Public Service (DPS). Described as an aid to the Department in drafting their “Ten Year Telecom Plan”, the survey contains eight questions, the first seven of which are simple multiple-choice queries about current internet and cell phone service at the respondent’s farm. The final question is the one that caught my eye:

“In what ways could your agriculture business be improved with better access to cell signal or higher speed internet service?”

Two things are immediately revealed by this question:

(a) The DPS believes that the only possible outcome from faster and better telecommunication access is that things will be “improved.”

(b) If you disagree with the DPS on point (a), they don’t want to hear about it.

A cynic might conclude that the DPS is only looking for survey results that justify decisions they’ve already made, and that’s probably true. But the department’s upbeat, one-dimensional outlook on technological change is actually the accepted norm in America. In his book In the Absence of the Sacred, Jerry Mander points out that new technologies are usually introduced through “best-case scenarios”: “The first waves of description are invariably optimistic, even utopian. This is because in capitalist societies early descriptions of new technologies come from their inventors and the people who stand to gain from their acceptance.” [1]

Silicon Valley entrepreneurs have made an art of utopian hype. Microsoft founder Bill Gates, one of high-tech’s most influential boosters, gave us such platitudes as “personal computers have become the most empowering tool we’ve ever created,”[2] and my favorite, “technology is unlocking the innate compassion we have for our fellow human beings.”[3]Other prognosticators include Facebook founder Mark Zuckerberg, who informs us that social media is “making the world more transparent” and “giving everyone a voice.” Needless to say, Gates, Zuckerberg and many others have become billionaires thanks to the public’s embrace of the technologies they touted.

The DPS survey reveals another shortcoming in how we look at technology: we tend to evaluate technologies solely in terms of their usefulness to us personally. Jerry Mander put it this way: “When we use a computer we don’t ask if computer technology makes nuclear annihilation more or less possible, or if corporate power is increased or decreased thereby. While watching television, we don’t think about the impact upon the tens of millions of people around the world who are absorbing the same images at the same time, nor about how TV homogenizes minds and cultures… If we have criticisms of technology they are usually confined to details of personal dissatisfaction.”

The DPS survey demonstrates this narrow focus: it only asks how faster telecommunications will affect the respondent’s “agriculture business”, while broader impacts – on family and community, on society as a whole and on the natural world – are out of bounds. A narrow focus is especially problematic when it comes to digital technologies, because the benefits they offer us as individuals – ultra-fast communication, the ability to access entertainment and information from all over the world – are so obvious that they can blind us to broader and longer-term impacts.

Recently, though – despite decades of hype and a continuing barrage of advertising –cracks are beginning to appear in the pro-digital consensus. The illusion that technology “unlocks compassion for our fellow human beings” has become harder to maintain in the face of what we now know: digital technologies are the basis for smart bombs, drone warfare and autonomous weaponry; they enable governments to conduct surveillance on virtually everyone, and allow corporations to gather and sell information about our habits and behavior; they permit online retailers to destroy brick-and-mortar businesses that are integral to healthy local economies.

We’ve also learned that social media doesn’t just enable us to connect with family and friends, it also provides a powerful recruitment tool for extremist groups – from neo-Nazis and white supremacists to ISIS. And all but the most die-hard Trump supporters acknowledge that social media was used to disrupt the democratic process in 2016, and that it is effectively used by authoritarian political leaders all over the world – including Mr. Trump – to spread false information and “alternative facts.”

People are even beginning to see that social media is not all that “empowering” for the individual. We recognize the addictive nature of internet use, though most of us don’t yet take it seriously: a friend will say, “I’m totally addicted to Facebook!” and we’ll just laugh. But it’s not a laughing matter: according to The American Journal of Psychiatry, “Internet addiction is resistant to treatment, entails significant risks, and has high relapse rates.”[4]The risks are highest among the young: a study of 14-24 year-olds in the UK found that social media “exacerbate children’s and young people’s body image worries, and worsen bullying, sleep problems and feelings of anxiety, depression and loneliness.”[5] Not surprisingly, a 2017 study in the US found that the suicide rate among teenagers has risen in tandem with their ownership of smartphones.[6]

Little of this should have been surprising within the digital design world. Facebook’s founding president, Sean Parker, now admits that the company knew from the start that they were creating an addictive product, one aimed at “exploiting a vulnerability in human psychology.” [7] Nir Eyal, corporate consultant and author of Hooked: How to Build Habit-Forming Products, acknowledges that “the technologies we use have turned into compulsions, if not full-fledged addictions… just as their designers intended.”[8]

These addictions have serious consequences not just for the individual, but for society as a whole: “The short-term, dopamine-driven feedback loops that we have created are destroying how society works. No civil discourse, no cooperation, misinformation, mistruth.” This is not the opinion of some left-leaning Luddite, but Facebook’s former vice-president for user growth, Chamath Palihapitiya.[9]

Digital technologies are a threat to democracy in ways that go deeper than even Vladimir Putin might hope. According to former Google strategist James Williams, “The dynamics of the attention economy are structurally set up to undermine the human will. If politics is an expression of our human will… then the attention economy is directly undermining the assumptions that democracy rests on.”[10]

There is also evidence that a child’s use of computers negatively affects their neurological development.[11] Tech insiders like Sean Parker may not know for certain “what it’s doing to our children’s brains,” but Parker isn’t taking any chances: “I can control my kids’ decisions, which is that they’re not allowed to use that shit.”[12] Lots of other Silicon Valley technologists are keeping their children away from screens, in part by sending them to private schools that prohibit the use of smartphones, tablets and laptops.[13] Meanwhile, the companies they work for continue to push their addictive products onto children worldwide: Alphabet, Google’s parent corporation, provides “free” tablets to public elementary schools, while Facebook recently launched a new app called Messenger Kids – aimed specifically at pre-teens.[14]

Much of the “best case scenario” for digital technology rests on its supposed environmental benefits (remember the “paperless society”?) But illusions about “clean” technology are dissolving in the horrific toxic wasteland of Boatou, China, where rare earth metals – needed for almost all digital devices – are mined and processed.[15] Another dirty secret is the cumulative energy demand of all these technologies: it’s estimated that within the next couple of years, internet-connected devices will consume more energy than aviation and shipping; by 2040 they will account for 14% of global greenhouse gas emissions – about the same proportion as the United States today.[16]

What does all this mean for ordinary citizens? For one, we need to begin looking beyond the immediate convenience that technologies offer us as individuals, and consider their broader impacts on community, society and nature. We should remain highly skeptical about the utopian claims of those who stand to profit from new technologies. And, perhaps most importantly, we need to allow our own children to grow up – as long as possible – in nature and community, rather than in a corporate-mediated technosphere of digital screens. Doing so will require us to challenge school boards and administrators who have been sold on the idea that putting elementary school children in front of screens is the best way to “prepare them for the future.”

As for the Department of Public Service, my survey response will say that the costs of improved telecom access would far outweigh the benefits. It would be of no consequence to my farm business, which by design only involves direct sales to nearby shops and individuals. More importantly, our farm is not only an “agriculture business” it is also our home, and that’s where the impact would be greatest. Better digital access would make it easier for me and members of my family to engage in addictive behavior, from online gambling and pornography to compulsive shopping, video games and internet “connectivity” itself. It would consume the attention of my children, leaving them more vulnerable to insecurity and depression, while displacing time better spent in nature or in face-to-face encounters with friends and neighbors. There are broader impacts as well: we would be increasingly tempted to buy our needs online, thus hurting local businesses and draining money out of our local economy. And almost everything we might do online would add a further increment to the growing wealth and influence of a handful of corporations – Amazon, Google, Facebook, Apple, and others – that are already among the most powerful in the world.

These are significant impacts. But the DPS doesn’t want to hear about them.

Notes

[1] Mander, Jerry (1991) In the Absence of the Sacred, Sierra Club: San Francisco.

[2] Speech at University of Illinois Urbana-Champaign, Feb. 24, 2004.

[3] “Bill Gates: Here’s my plan to improve our world – and how you can help”, Wired magazine, November 12, 2013

[4] Konnikova, Maria, “Is Internet Addiction a Real Thing?” The New Yorker, November 26, 2014.

[5] Campbell, Dennis, “Facebook and Twitter ‘harm young people’s mental health’”, The Guardian, May 19, 2017.

[6] “Teen suicide rate suddenly rises with heavy use of smartphones, social media,” Washington Times, Nov. 14, 2017.

[7] Solon, Olivia, “Ex-Facebook president Sean Parker: site made to exploit human ‘vulnerability’”, The Guardian, November 9, 2017.

[8] Lewis, Paul, “’Our minds can be hijacked’: the tech insiders who fear a smartphone dystopia”, The Guardian, October 6, 2017.

[9] Wong, Julia Carrie, “Former Facebook executive: social media is ripping society apart”, The Guardian, December 12, 2017

[10] Lewis, P. op. cit.

[11] Carr, Nicholas (2010) The Shallows: What the Internet Is Doing to Our Brains, W.W. Norton.

[12] Wong, Julia Carrie, op. cit.

[13] Lewis, P. op. cit.

[14] Kircher, Madison Malone, “Facebook Releases App for Kids Under 13. What Could Possibly Go Wrong Here?” New York Magazine, December 4, 2017.

[15] Maughan, Tim, “The dystopian lake filled by the world’s tech lust”, BBC Future, April 2, 2015.

[16] “’Tsunami of data’ could consume one-fifth of global electricity by 2025”, The Guardian, December 11, 2017.

by Deep Green Resistance News Service | Feb 8, 2018 | Alienation & Mental Health

by John F Schumaker / New Internationalist

Our descent into the Age of Depression seems unstoppable. Three decades ago, the average age for the first onset of depression was 30. Today it is 14. Researchers such as Stephen Izard at Duke University point out that the rate of depression in Western industrialized societies is doubling with each successive generational cohort. At this pace, over 50 per cent of our younger generation, aged 18-29, will succumb to it by middle age. Extrapolating one generation further, we arrive at the dire conclusion that virtually everyone will fall prey to depression.

By contrast to many traditional cultures that lack depression entirely, or even a word for it, Western consumer culture is certainly depression-prone. But depression is so much a part of our vocabulary that the word itself has come to describe mental states that should be understood differently. In fact, when people with a diagnosis of depression are examined more closely, the majority do not actually fit that diagnosis. In the largest study of its kind, Ramin Mojtabai of Johns Hopkins Bloomberg School of Public Health sampled over 5,600 cases and found that only 38 per cent of them met the criteria for depression.

Contributing to the confusion is the equally insidious epidemic of demoralization that also afflicts modern culture. Since it shares some symptoms with depression, demoralization tends to be mislabelled and treated as if it were depression. A major reason for the poor 28-per-cent success rate of anti-depressant drugs is that a high percentage of ‘depression’ cases are actually demoralization, a condition unresponsive to drugs.

Existential disorder

In the past, our understanding of demoralization was limited to specific extreme situations, such as debilitating physical injury, terminal illness, prisoner-of-war camps, or anti-morale military tactics. But there is also a cultural variety that can express itself more subtly and develop behind the scenes of normal everyday life under pathological cultural conditions such as we have today. This culturally generated demoralization is nearly impossible to avoid for the modern ‘consumer’.

Rather than a depressive disorder, demoralization is a type of existential disorder associated with the breakdown of a person’s ‘cognitive map’. It is an overarching psycho-spiritual crisis in which victims feel generally disoriented and unable to locate meaning, purpose or sources of need fulfilment. The world loses its credibility, and former beliefs and convictions dissolve into doubt, uncertainty and loss of direction. Frustration, anger and bitterness are usual accompaniments, as well as an underlying sense of being part of a lost cause or losing battle. The label ‘existential depression’ is not appropriate since, unlike most forms of depression, demoralization is a realistic response to the circumstances impinging on the person’s life.

Resilience traits such as patience, restraint and fortitude have given way to short attention spans, over-indulgence and a masturbatory approach to life

As it is absorbed, consumer culture imposes numerous influences that weaken personality structures, undermine coping and lay the groundwork for eventual demoralization. Its driving features – individualism, materialism, hyper-competition, greed, over-complication, overwork, hurriedness and debt – all correlate negatively with psychological health and/or social wellbeing. The level of intimacy, trust and true friendship in people’s lives has plummeted. Sources of wisdom, social and community support, spiritual comfort, intellectual growth and life education have dried up. Passivity and choice have displaced creativity and mastery. Resilience traits such as patience, restraint and fortitude have given way to short attention spans, over-indulgence and a masturbatory approach to life.

Research shows that, in contrast to earlier times, most people today are unable to identify any sort of philosophy of life or set of guiding principles. Without an existential compass, the commercialized mind gravitates toward a ‘philosophy of futility’, as Noam Chomsky calls it, in which people feel naked of power and significance beyond their conditioned role as pliant consumers. Lacking substance and depth, and adrift from others and themselves, the thin and fragile consumer self is easily fragmented and dispirited.

By their design, the central organizing principles and practices of consumer culture perpetuate an ‘existential vacuum’ that is a precursor to demoralization. This inner void is often experienced as chronic and inescapable boredom, which is not surprising. Despite surface appearances to the contrary, the consumer age is deathly boring. Boredom is caused, not because an activity is inherently boring, but because it is not meaningful to the person. Since the life of the consumer revolves around the overkill of meaningless manufactured low-level material desires, it is quickly engulfed by boredom, as well as jadedness, ennui and discontent. This steadily graduates to ‘existential boredom’ wherein the person finds all of life uninteresting and unrewarding.

Moral net

Consumption itself is a flawed motivational platform for a society. Repeated consummation of desire, without moderating constraints, only serves to habituate people and diminish the future satisfaction potential of what is consumed. This develops gradually into ‘consumer anhedonia’, wherein consumption loses reward capacity and offers no more than distraction and ritualistic value. Consumerism and psychic deadness are inexorable bedfellows.

Individualistic models of mind have stymied our understanding of many disorders that are primarily of cultural origin. But recent years have seen a growing interest in the topic of cultural health and ill-health as they impact upon general wellbeing. At the same time, we are moving away from naïve behavioural models and returning to the obvious fact that the human being has a fundamental nature, as well as a distinct set of humanneeds, that must be addressed by a cultural blueprint.

In his groundbreaking book The Moral Order, anthropologist Raoul Naroll used the term ‘moral net’ to indicate the cultural infrastructure that is required for the mental wellbeing of its members. He used numerous examples to show that entire societies can become predisposed to an array of mental ills if their ‘moral net’ deteriorates beyond a certain point. To avoid this, a society’s moral net must be able to meet the key psycho-social-spiritual needs of its members, including a sense of identity and belonging, co-operative activities that weave people into a community, and shared rituals and beliefs that offer a convincing existential orientation.

We are long overdue a cultural revolution that would force a radical revamp of the political process, economics, work, family and environmental policy

Similarly, in The Sane Society, Erich Fromm cited ‘frame of orientation’ as one of our vital ‘existential needs’, but pointed out that today’s ‘marketing characters’ are shackled by a cultural programme that actively blocks fulfilment of this and other needs, including the needs for belonging, rootedness, identity, transcendence and intellectual stimulation. We are living under conditions of ‘cultural insanity’, a term referring to a pathological mismatch between the inculturation strategies of a culture and the intrapsychic needs of its followers. Being normal is no longer a healthy ambition.

Human culture has mutated into a sociopathic marketing machine dominated by economic priorities and psychological manipulation. Never before has a cultural system inculcated its followers to suppress so much of their humanity. Leading this hostile takeover of the collective psyche are increasingly sophisticated propaganda and misinformation industries that traffic the illusion of consumer happiness by wildly amplifying our expectations of the material world. Today’s consumers are by far the most propagandized people in history. The relentless and repetitive effect is highly hypnotic, diminishing critical faculties, reducing one’s sense of self, and transforming commercial unreality into a surrogate for meaning and purpose.

The more lost, disoriented and spiritually defeated people become, the more susceptible they become to persuasion, and the more they end up buying into the oversold expectations of consumption. But in unreality culture, hyper-inflated expectations continually collide with the reality of experience. Since nothing lives up to the hype, the world of the consumer is actually an ongoing exercise in disappointment. While most disappointments are minor and easy to dissociate, they accumulate into an emotional background of frustration as deeper human needs get neglected. Continued starvation of these needs fuels disillusion about one’s whole approach to life. Over time, people’s core assumptions can become unstable.

Culture proofing

At its heart, demoralization is a generalized loss of credibility in the assumptions that ground our existence and guide our actions. The assumptions underpinning our allegiance to consumerism are especially vulnerable since they are fundamentally dehumanizing. As they unravel, it becomes increasingly difficult to identify with the values, goals and aspirations that were once part of our consumer reality. The consequent feeling of being forsaken and on the wrong life track is easily mistaken for depression, or even unhappiness, but in fact it is the type of demoralization that most consumer beings will experience to some degree.

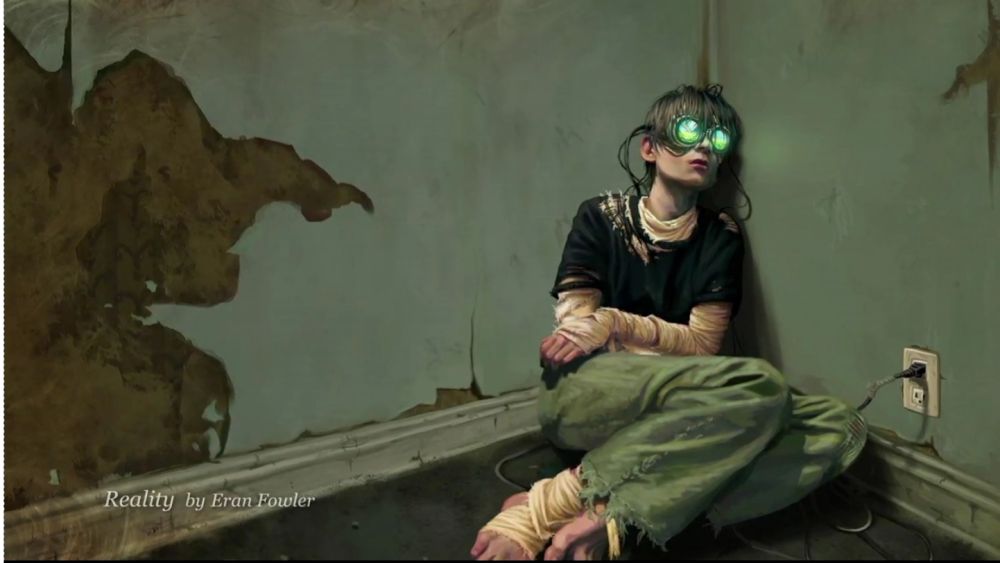

For the younger generation, the course of boredom, disappointment, disillusion and demoralization is almost inevitable. As the products of invisible parents, commercialized education, cradle-to-grave marketing and a profoundly boring and insane cultural programme, they must also assimilate into consumer culture while knowing from the outset that its workings are destroying the planet and jeopardizing their future. Understandably, they have become the trance generation, with an insatiable appetite for any technology that can downsize awareness and blunt the emotions. With society in existential crisis, and emotional life on a steep downward trajectory, trance is today’s fastest-growing consumer market.

Once our collapsed assumptions give way to demoralization, the problem becomes how to rebuild the unconscious foundations of our lives. In their present forms, the psychology and psychiatry professions are of little use in treating disorders that are rooted in culture and normality. While individual therapy will not begin to heal a demoralized society, to be effective such approaches must be insight-oriented and focused on the cultural sources of the person’s assumptions, identity, values and centres of meaning. Cultural deprogramming is essential, along with ‘culture proofing’, disobedience training and character development strategies, all aimed at constructing a worldview that better connects the person to self, others and the natural world.

The real task is somehow to treat a sick culture rather than its sick individuals. Erich Fromm sums up this challenge: ‘We can’t make people sane by making them adjust to this society. We need a society that is adjusted to the needs of people.’ Fromm’s solution included a Supreme Cultural Council that would serve as a cultural overseer and advise governments on corrective and preventive action. But that sort of solution is still a long way off, as is a science of culture change. Democracy in its present guise is a guardian of cultural insanity.

We are long overdue a cultural revolution that would force a radical revamp of the political process, economics, work, family and environmental policy. It is true that a society of demoralized people is unlikely to revolt even though it sits on a massive powder keg of pent-up frustration. But credibility counteracts demoralization, and this frustration can be released with immense energy when a credible cause, or credible leadership, is added to the equation.

It might seem that credibility, meaning and purposeful action would derive from the multiple threats to our safety and survival posed by the fatal mismatch between consumer culture and the needs of the planet. The fact that it has not highlights the degree of demoralization that infects the consumer age. With its infrastructure firmly entrenched, and minimal signs of collective resistance, all signs suggest that our obsolete system – what some call ‘disaster capitalism’ – will prevail until global catastrophe dictates for us new cultural directions.

John F Schumaker is a retired psychology academic living in Christchurch, New Zealand/Aotearoa.

Reprinted by kind permission of New Internationalist. Copyright New Internationalist. www.newint.org

by Deep Green Resistance News Service | Dec 14, 2017 | Alienation & Mental Health

by Max Wilbert / Deep Green Resistance

Last night, I dreamt that I was trapped in a box.

I was in high school again, sitting at an antique desk with a wraparound writing surface (right-handed of course, for a left-handed child) and I was more bored than any person should ever be. As the teacher played out their sanctioned role, trying to make compulsory education “fun” and “engaging,” I sat in a stupor, craving some stimulation lest the torpor become permanent and turn me into a compliant drone for life.

I refused to be turned into a cubicle occupant. In the dream, my solution was to stand up and start removing the bug screens from the windows. My boredom was temporarily cast aside, and the fresh air flowed into the classroom, enlivening the other occupants, reminding them of the real world. The teacher frowned in annoyance.

It was a win-win. A small act of rebellion, no doubt, but I would not be cowed into sitting meekly.

This dream could have been a flashback. I behaved this way in high school, pushing the boundaries as far as I could, ignoring teachers unless they earned my respect (and even then ignoring rules that seemed silly to me), giving friendship only to those teachers who in turn pushed the boundaries. I respected them as people, but after all, they were being paid to attend school. I was legally obligated.

Education can be a great experience, but at least here in the United States, the school system exists entirely to serve the dominant economic system. Grades separate out those with the combination of traits—intelligence (defined in the most culturally blinkered and capitalist terms) and obedience—that make them suitable to be the next managers. Those who fail will make up the poor and working class from which wealth will be extracted. Punitive measures and the brutal, relentless school-to-prison pipeline enforce and inculcate white supremacy.

It’s the Prussian educational model, barely modified in the last 250 years.

Industrial schooling also deepens the damage caused by abuse, homelessness, and neglect. Children in distress, far from receiving the love and care and attention that they need, are expected to sit still, shut up, and play nicely. The school system’s academic framework not only fails to serve these kids; it makes everything worse. Bullying, social competition, stigmatization, criminalization, and social cliques that mature in full-blown xenophobia are the inevitable results of a framework designed for one demographic: white, bourgeois, nuclear-family, patriarchal households.

As a system of education and social control within a brutal empire built on slavery, imperialism, and land theft, our schools function perfectly.

I’m all for reform. Small improvements are meaningful where they can be made. My 10th grade journalism teacher kept me—and countless others—thinking critically with his hard-hitting analysis of how advertising and mass media manipulates thought to encourage racism, nationalism, warmongering, consumerism, and objectification. There were a few other bright spots, islands of sanity in an ocean of conformity to the status quo.

But by itself, reform is never enough. The school system isn’t broken; it’s functioning exactly as it was meant to. Liberalism’s incessant focus on education as the solution to social problems channels endless streams of idealistic young people into the school system, where they are almost inevitably broken by endless bureaucracy and 50-hour work weeks. Otherwise that energy could be put to revolutionary purposes, and that doesn’t suit the system.

My dream last night reminded me of the truth. School, far from enlightening us, is stultifying. The school system—like capitalism, like American empire, like industrial civilization—is functionally irredeemable. Beyond a certain point, it’s incapable of being meaningfully reformed. Sure, improvements can (and should) be made. But might we be better off just scrapping the whole thing and starting from scratch?

I’ve been told that in Mohawk culture, children are treated as “miniature adults,” and are expected to learn mainly through participation in the activities of the community. Real learning comes from being embedded in a functional community engaging in the tasks of survival and self-governance—not from being trapped in a box.

This is taken so seriously that children remained beyond the barricades during the Oka standoff near Montreal in 1990, standing with the warrior societies as the Canadian military flexed its colonial muscle to stifle indigenous sovereignty. We can learn from this level of commitment to teaching children things that have real value, and exposing them to the real world.

In a world flush with refugees, overwhelmed by neo-colonialism, sweltering under global warming, sweating in fear of rising fascist elements, and yoked with the chains of sex and race oppression, perhaps it’s time we gave up on the school system and started working to tear it, and the system it supports, down.

***

Max Wilbert is a writer, activist, and organizer with the group Deep Green Resistance. He lives on occupied Kalapuya Territory in Oregon.

To repost this or other DGR original writings, please contact newsservice@deepgreenresistance.org

by Deep Green Resistance News Service | Nov 26, 2017 | Alienation & Mental Health

Violence and Its Aftermath

by Derrick Jensen

A different version of this interview appeared in A Language Older Than Words

Derrick Jensen: What is the relationship between atrocity and silence?

Judith Herman: Atrocities are actions so horrifying they go beyond words. For people who witness or experience atrocities, there is a kind of silencing that comes from not knowing how to put these experiences into words. At the same time, atrocities are the crimes perpetrators most want to hide. This creates a powerful convergence of interest: No one wants to speak about them. No one wants to remember them. Everyone wants to pretend they didn’t happen.

DJ: In Trauma and Recovery, you write, “In order to escape accountability the perpetrator does everything in his power to promote forgetting.”

JH: This is something with which we are all familiar. It seems that the more extreme the crimes, the more dogged and determined the efforts to deny that the crimes happened. So we have, for example, almost a hundred years after the fact, an active and apparently state-sponsored effort on the part of the Turkish government to deny there was ever an Armenian genocide. We still have a whole industry of Holocaust denial. I just came back from Bosnia where, because there hasn’t been an effective medium for truth-telling and for establishing a record of what happened, you have the nationalist governmental entities continuing to insist that ethnic cleansing didn’t happen, that the various war crimes and atrocities committed in that war simply didn’t occur.

DJ: How does this happen?

JH: On the most blatant level, it’s a matter of denying the crimes took place. Whether it’s genocide, military aggression, rape, wife beating, or child abuse, the same dynamic plays itself out, beginning with an indignant, almost rageful denial, and the suggestion that the person bringing forward the information–whether it’s the victim or another informant–is lying, crazy, malicious, or has been put up to this by someone else. Then of course there are a number of fallback positions to which perpetrators can retreat if the evidence is so overwhelming and irrefutable it cannot be ignored, or rather, suppressed. This, too, is something we’re familiar with: the whole raft of predictable rationalizations used to excuse everything from rape to genocide: the victim exaggerates; the victim enjoyed it; the victim provoked or otherwise brought it on herself; the victim wasn’t really harmed; and even if some slight damage has been done, it’s now time to forget the past and get on with our lives: in the interests of preserving peace–or in the case of domestic violence, preserving family harmony–we need to draw a veil over these matters. The incidents should never be discussed, and preferably they should be forgotten altogether.

DJ: Something I wonder, as I watch corporate spokespeople utter absurdities to defend, for example, the polluting of rivers or the poisoning of children, is whether these people believe their own claims. I’ll give an example: I live less than three miles from the Spokane River, in Washington state, which begins about forty miles east of here as it flows out of Lake Coeur d’Alene. Lake Coeur d’Alene, one of the most beautiful lakes in the world, is also one of the most polluted with heavy metals. There are days when more than a million pounds of lead drains into the lake from mine tailings on the South Fork of the Coeur d’Alene River. Hundreds of migrating tundra swans die here each year from lead poisoning as they feed in contaminated wetlands. Some of the highest blood lead levels ever recorded in human beings were from children in this area. Yet just last summer the Spokesman-Review, the paper of record for the region, wrote that concern over this pollution is unnecessary because “there are no dead [human] bodies washing up on the river banks.” To return to the original question, to what degree do both perpetrators and their apologists believe their own claims? Did my father, to provide another example, really believe his claims that he wasn’t beating us?

JH: Do perpetrators believe their own lies? I have no idea, and I don’t have much trust in those who claim they do. Certainly we in the mental health profession don’t have a clue when it comes to what goes on in the hearts and minds of perpetrators of either political atrocities or sexual and domestic crimes.

For one thing, we don’t get to know them very well. They aren’t interested in being studied–by and large they don’t volunteer–so we study them when they’re caught. But when they’re caught, they tell us whatever they think we want to hear.

This leads to a couple of problems. The first is that we have to wend our way through lies and obfuscation to attempt to discover what’s really going on. The second problem is even larger and more difficult. Most of the psychological literature on perpetrators is based on studies of convicted or reported offenders, which represents a very small and skewed, unrepresentative group. If you’re talking about rape, for example, since the reporting rates are, by even the most generous estimates, under twenty percent, you lose eighty percent of the perpetrators off the top. Your sample is reduced further by the rates at which arrests are made, charges are filed, convictions are obtained, and so forth, which means convicted offenders represent about one percent of all perpetrators. Now, if your odds of being caught and convicted of rape are basically one in one hundred, you have to be extremely inept to become a convicted rapist. Thus, the folks we are normally able to study look fairly pathetic, and often have a fair amount of psychopathology and violence in their own histories. But they’re not representative of your ordinary, garden-variety rapist or torturer, or the person who gets recruited to go on an ethnic cleansing spree. We don’t know much about these people. And the one thing victims say most often is that these people look normal, and that nobody would have believed it about them. That was true even of Nazi war criminals. From a psychiatric point of view, these people didn’t look particularly disturbed. In some ways that’s the scariest thing of all.

DJ: Given the misogyny, genocide, and ecocide endemic in our culture, I wonder how much of that normality is only seeming.

JH: If you’re part of a predatory and militaristic culture, then to behave in a predatory and exploitative way is not deviant, per se. Of course there are rules as to who, if you want to use these terms, might be a legitimate victim, a person who may be attacked with impunity. And most perpetrators are exquisitely sensitive to these rules.

DJ: To your understanding, what are the levels of rape and childhood sexual abuse in this country?

JH: The best data we have is that one of four women will be raped over a lifetime. For childhood sexual abuse I like to quote Diana Russell’s data, which I believe is still the standard by which these studies are measured. She asked a random sample of 900 and some women to participate in a survey of crime victimization. The interviews were in-depth, and conducted in the subjects’ native languages by trained interviewers. She found that 38 percent of females had a childhood experience that met the criminal code definition of sexual assault. Some people have said that because Russell’s study was done in California, it’s not representative, but the results from other studies have been, while slightly lower, still in the same ballpark. It’s a common experience. It’s less common for boys, but there is still a substantial risk for them as well.

DJ: I remember reading something like 7 to 10 percent.

JH: I’d say a fair estimate would be around ten percent for boys, and two to three times that for girls. It is a little more difficult to determine levels of sexual abuse for boys, because most are victimized by male perpetrators, which adds a layer of secrecy and shame to the child’s experience.

DJ: This is a huge percentage of the population which has been severely traumatized. Why isn’t this front page news every day?

JH: Actually there is a point to be made here as well. One of the questions Diana asked her informants who disclosed childhood abuse was: What impact do you think this has had on your life? Only about one in four said it had done great or long-lasting damage. Virtually everyone said, “It was horrible at the time, and I hated it.” But half of the women considered themselves to have recovered reasonably well, and didn’t see that it had affected their lives in a major way. I say this not to minimize the importance of what happened, but to give due respect and recognition to the resilience and resourcefulness of victims, most of whom recover without any formal intervention.

Part of the reason for this is that not all traumas are equal. Diana and I took a look at the factors that seemed to lead to long-lasting impact, and they were the kinds of things you would expect. Women who reported prolonged, repeated abuse by someone close–father, stepfather, or another member of the immediate family–abuse that was very violent, that involved a lot of bodily invasion, or that involved elements of betrayal were the ones who had the most difficulty recovering.

But you were asking why this isn’t front page news. The answer is partly that this isn’t new. And it’s also not something unique to this country. Wherever studies of comparable sophistication are carried out, the numbers are pretty much the same. We may have a lot more street and handgun violence than, for example, Northern Europe and Scandinavia, but private crimes are an international phenonemon.

DJ: But they aren’t ubiquitous to all human cultures. I’ve read in multiple sources that prior to contact with our culture there have been some indigenous cultures in which rape and child abuse were rare or nonexistent. I know that the Okanagan Indians of what is now British Columbia, for example, had no word in their language for either rape or child abuse. They did have a word that meant the violation of a woman. Literally translated it meant someone looked at me in a way I don’t like.

JH: I think it would be hard to establish that rape was nonexistent in a culture. How would you determine that? But you can certainly say there is great variation. The anthropologist Peggy Reeves Sanday looked at data from over one hundred cultures as to the prevalence of rape, and divided them into high- or low-rape cultures. She found that high rape cultures are highly militarized and sex segregated. There is a lot of difference in status between men and women. The care of children is devalued and delegated to subordinate females. She also found that the creation myths of high rape cultures recognize only a male deity rather than a female deity or a couple. When you think about it, that is rather bizarre. It would be an understandable mistake to think women make babies all by themselves, but it’s preposterous to think men do that alone. So you’ve got to have a fairly elaborate and counterintuitive mythmaking machine in order to fabricate a creation myth that recognizes only a male deity. There was another interesting finding, which is that high rape cultures had recent experiences–meaning in the last few hundred years–of famine or migration. That is to say, they had not reached a stable adaptation to their ecological niche.

Sadly enough, when you tally these risk factors, you realize you’ve pretty much described our culture.

DJ: I’d like to back up for a moment to define some terms. Can you tell me more about the phenomenon of psychological trauma?

JH: Trauma occurs when people are subjected to experiences that involve extreme terror, a life threat, or exposure to grotesque violence. The essential ingredient seems to be the condition of helplessness.

In the aftermath of such experiences it is normal and predictable that traumatized people will experience particular symptoms of psychological distress. Most people experience these transiently, and recover more or less spontaneously. Others go on to have prolonged symptoms we’ve come to call Post Traumatic Stress Disorder (PTSD).

It’s important to note, by the way, that PTSD doesn’t merely affect “helpless” women and children. We see it in combat veterans. We see it in prisoners of war. Concentration camp survivors. We see it with survivors of natural disasters, fires, and industrial and automobile accidents. We see it in cops. Sophisticated police departments now include traumatic stress debriefing for their officers involved in any sort of critical incident such as a shooting. They had discovered that within two years of involvement in a critical incident, enormous numbers of well-trained, valuable, experienced police officers were being lost to disabilities, physical complaints, substance abuse, or psychiatric problems. We see it in firefighters who have to rescue people from burning buildings, and who sometimes have to bring out dead bodies. We see it in rescue workers who have to clear away bodies after a flood or earthquake. We see it most commonly in the civilian casualties, if you will, of our private war against women and children, that is, the survivors of rape and domestic violence.

DJ: What are the symptoms?

JH: It’s easiest to think about symptoms in three categories. The first are called symptoms of hyperarousal. In the aftermath of a terrifying experience people see danger everywhere. They’re jumpy, they startle easily, and they have a hard time sleeping. They’re irritable, and more prone to anger. This seems to be a biological phenomenon, not just a psychological one.

The second thing that happens is that people relive the experience in nightmares and flashbacks. Any little reminder can set them off. For example, a Vietnam veteran involved in helicopter combat might react years later when a news or weather helicopter flies overhead.

DJ: All through my teens and twenties when someone would ask me to go water skiing, my response externally would be to say, “No, thanks,” but my internal response was, “Fuck you.” I never could figure out why until a few years ago I asked my mom, and she said that there were beatings associated with water skiing trips when I was a small child. I never knew that. I just always knew that water skiing pissed me off.

JH: Sometimes people understand the trigger, but sometimes they won’t have complete memory of the event. They may respond to the reminder as you did, by becoming terrified or agitated or angry.

DJ: And it doesn’t have to be so dramatic as the stereotypical Vietnam vet who goes berserk when he hears a car backfire.

JH: A lot of times it’s more subtle. Someone who was raped in the backseat of a car may have a lot of feelings everytime she gets into a car, particularly one that resembles the one in which she was raped.

This reliving, these intrusions, are not a normal kind of remembering, where the smell of cinammon rolls, for example, may remind you of your grandmother. Instead, people say it’s like playing the same videotape over and over. It’s a repetitive and often wordless reexperiencing. People remember the smells, the sounds, or if it was raining, if it was cold. The images. It was dark. Sexual abuse survivors often say, “I felt like I was smothering. I thought I was going to choke.” But it’s very hard for people to remember it in a kind of fluid verbal narrative that is modifiable according to the circumstances. People can’t give you the short form and the long form, and describe it differently and understand it differently over time. It’s just a repetitive sequence of terrifying images and sensations.

DJ: Is that symptom also physiological?

JH: Oh, yes. Studies have shown that traumatic memories are perceived and encoded in the brain differently from regular memories.

The third group of symptoms that people have–and these are almost the opposite of the intrusive nightmares and flashbacks, the dramatic symptoms–is a shutting down of feelings, a constriction of emotions, intellect, and behavior. It’s characteristic of people with PTSD to oscillate between feeling overwhelmed, enraged, terrified, desperate, or in extreme grief and pain, and feeling nothing at all. People describe themselves as numb. They don’t feel anything, they aren’t interested in things that used to interest them, they avoid situations that might remind them of the trauma. You, for example, probably avoided water skiing in order to avoid the traumatic memories. Water skiing may not be much to give up, but people sometimes avoid relationships, they avoid sexuality, they make their lives smaller, in an attempt to stay away from the overwhelming feelings.

In addition, one finds all kinds of physical complaints. In fact, the more the culture shames people for admitting psychological weakness, the more these symptoms manifest themselves physically. Rather than seeking psychological help, people go to the doctor seeking sleeping pills, or go to the neighborhood bar to get the number one psychoactive drug available without prescription, which is alcohol. We see a lot of alcohol and substance abuse as a secondary complication of PTSD.

DJ: Where does dissociation fit into all this?

JH: It’s central. Dissociation itself is really quite fascinating, and I don’t think any of us can quite pretend to understand it. We all seem to have the capacity to dissociate, though for some people the capacity is greater. And certain circumstances seem to call it up: it involves a mental escape from experience at a time when physical escape is impossible.

When I teach, I quite often use automobile accidents to exemplify this. I’ll ask people, “Can you describe what it was like in the moment before impact, the moment of impact, and the moment after?”

People often describe a sense of derealization: this isn’t happening. They also describe depersonalization: this is happening, but to someone else, while I sit outside watching the crash and feeling very sorry for the person in the car. They may feel as though they’re watching a movie. They describe a slowing of time. They describe a sense of tunnel vision, where they focus only on a few details such as sounds or smells or imagery, but where context and peripheral detail fall away. Some people describe alterations of pain perception; we’ve all heard stories of people who walk on broken legs until they get to safety, and then collapse, or people who are able to ignore their own pain while they rescue others. And then, of course, some people have amnesia. Memory gaps in the aftermath. They’ll say, “I remember the moment before, and then the next thing I know I was on the shoulder outside the car.” Even with no head trauma and no loss of consciousness, there will often be a loss of memory. All of these, of course, are not specific to car wrecks, but happen with all sorts of psychological trauma.

DJ: Dissociation sounds like a very good thing.

JH: You’d think so. But more and more of the research is zeroing in on dissociation as a predictor of more longlasting symptoms. For example, some studies were done after the San Francisco earthquake, and the Oakland fire, two big disasters that happened in the last decade. Each is a single event that affected lots of people, and invoked large-scale responses by emergency personnel. So researchers had a couple of chances to interview and examine many survivors, and then to call them up three, six, and more months later to see how they were doing. Well, the folks who dissociated during the earthquake turned out to be more likely to have PTSD later. There seems to be something about that altered state of consciousness that is protective at the moment, but gets you into trouble later on. By the way, people who dissociated at the time of the fire also tended to lose some of their adaptive coping in the moment. They either behaved helplessly, almost like zombies or as if they were paralyzed, or they lost the capacity to judge danger realistically. The rescue people had the most trouble with this latter group, because they would insist on going back into burning houses to rescue possessions or animals. They exposed themselves to danger, seemingly heedless of the consequences.

DJ: What’s the difference between trauma and captivity?

JH: Trauma can emerge from a single event like a fire, earthquake, or auto accident, where you’re in the situation, you survive it, and then you get on with your life. You may continue to relive it in fantasy, but it’s not happening over and over. Even if you live in an earthquake or flood zone you still have a choice as to whether to rebuild or move away.

Based on my work with domestic abuse survivors, as well as victims of political terror, I began to ask: What happens when a person is exposed not to a single terrifying incident, but rather to prolonged, repeated trauma? I came to understand the similarities between concentration or slave labor camps or torture situations on the one hand, and on the other hand, the situation of domestic or sexual violence, where the perpetrator may beat or sexually abuse his wife or children for years on end. We see this also in the sex trade, where there’s a criminally organized traffic in women and kids, and we sometimes see this sort of captivity in some religious cults, where people are not free to leave.

In situations where the trauma happens over and over, and where it is imposed by human design (as opposed to the effects of weather, or some other nonhuman force), one sees a series of personality changes in addition to simple PTSD. People begin to lose their identity, their self-respect. They begin to lose their autonomy and independence.

Because people in captivity are most often isolated from other relationships–that this is so in normal captivity is obvious and intentional, but it is overwhelmingly the case in domestic violence as well, as perpetrators often demand their victims increasingly cut all other social ties–they are forced to depend for basic survival on the very person who is abusing them. This creates a complicated bond between the two, and it skews the victim’s perception of the nature of human relationships. The situation is even worse for children raised in these circumstances, because their personality is formed in the context of an exploitative relationship, in which the overarching principles are those of coercion and control, of dominance and subordination.

Whether we are talking about adults or children, it often happens that a kind of sadistic corruption enters into the captive’s emotional relational life. People lose their sense of faith in themselves, in other people. They come to believe or view all relationships as coercive, and come to feel that the strong rule, the strong do as they please, that the world is divided into victims, perpetrators, bystanders, and rescuers. They believe that all human relations are contaminated and corrupted, that sadism is the principle that rules all relationships.

DJ: Might makes right. “Social Darwinism.” The selfish gene theory. You’ve just described the principles that undergird our political and economic systems.

JH: And there are other losses involved. A loss of basic trust. A loss of feeling of mutuality of relatedness. In its stead is emplaced a contempt for self and others. If you’ve been punished for showing autonomy, initiative, or independence, after a while you’re not going to show them. In the aftermath of this kind of brutalization, victims have a great deal of difficulty taking responsibility for their lives. Often, people who try to help get frustrated because we don’t understand why the victims seem so passive, seem so unable to extricate themselves or to advocate on their own behalf. They seem to behave as though they’re still under the perpetrator’s control, even though we think they’re now free. But in some ways the perpetrator has been internalized.

Captivity also creates disturbances in intimacy, because if you view the world as a place where everyone is either a victim, a perpetrator, an indifferent or helpless bystander, or a rescuer, there’s no room for relationships of mutuality, for cooperation, for responsible choices. There’s no room to follow agreements through to everyone’s mutual satisfaction. The whole range of cooperative relational skills, and all the emotional fulfillment that goes with them, is lost. And that’s a great deal to lose.

DJ: It seems to me that part of the reason for this loss is not simply the physical trauma itself, but also the fact that the traumatizing actions can’t be acknowledged.

JH: And much more broadly, because they take place within a relationship motivated by a need to dominate, and in which coercive control is the central feature.

When I teach about this, I describe the methods of coercive control perpetrators use. It turns out that violence is only one of the methods, and it’s not even one of the most frequent. It doesn’t have to be used all that often; it just has to be convincing. In the battered women’s movement, there’s a saying: “One good beating lasts a year.”

DJ: What constitutes a good beating?

JH: If it’s extreme enough, when the victim looks into the eyes of the perpetrator she realizes, “Oh, my God, he really could kill me.”

What goes along with this violence are other methods of coercive control that have as their aim the victim’s isolation, and the breakdown of the victim’s resistance and spirit.

DJ: Such as?

JH: You have capricious enforcement of lots of petty rules, and you have concomitant rewards. Prisoners and hostages talk about this all the time: if you’re good, maybe they’ll let you take a shower, or give you something extra to eat. You have the monopolization of perception that follows from the closing off of any outside relationships or sources of information. Finally, and I think this is the thing that really breaks people’s spirits, perpetrators often force victims to engage in activities that the victims find morally reprehensible or disgusting. Once you’ve forced a person to violate his or her moral codes, to break faith with him- or herself–the fact that it’s done under duress does not remove the shame or guilt of the experience–you may never again even need to use threats. At that point the victim’s self-hatred, self-loathing, and shame will be so great that you don’t have to beat her up, because she’s going to do it herself.

DJ: That reminds me of something I read about those who collaborated with the Nazis: “A man who had knowingly compromised himself did not revolt against his masters, no matter what idea had driven him to collaboration: too many mutual skeletons in the closet. . . . There were so many proofs of the absolute obedience that could be expected of men of honor who had drifted into collaboration.”

JH: Perpetrators know this. These methods are known, they’re taught. Pimps teach them to one another. Torturers in the various clandestine police forces involved in state-sponsored torture teach them to each other. They’re taught at taxpayer expense at our School of the Americas. The Nazi war criminals who went to Latin America passed on this knowledge. It is apparently a point of pride among many Latin American torturers that they have come up with techniques the Nazis didn’t know about.

DJ: We’ve spent a lot of time delving into the abyss, and I think what I would like to do now is emerge on the other side. But first, there’s something else about victims I would like to explore. You’ve written that symptoms of PTSD can be interpreted as attempts to tell their story.

JH: People not only relive the experiences in memory, but sometimes behave in ways that reenact the trauma. So a combat vet with PTSD might sign up for especially risky duty, or reenlist in the special forces. Later he may get a job in another high risk line of work. A sexual survivor may engage in behaviors likely to result in another victimization. Especially regarding revictimization after child abuse, the data are really very sobering. One way to view all this is that the person is trying desperately to tell the story, in action if necessary. That’s a bit teleological, but we do know that when people are finally able to put their experiences into words in a relational context, where they can be heard and understood, they often get quite a bit of relief.

DJ: You wrote in Trauma and Recovery that “When the truth is finally recognized, survivors can begin their recovery.” How does that work? What happens inside survivors when the truth is recognized?

JH: I wish I knew. It’s miraculous. I don’t understand it. I just observe it, and try to facilitate it. I think it’s a natural healing process that has to do with the restoration of human connection and agency. If you think of trauma as the moment when those two things are destroyed, then there is something about telling the trauma story in a place where it can be heard and acknowledged that seems to restore both agency and connection. The possibility of mutuality returns. People feel better.

The most important principles for recovery are restoring power and choice or control to the person who has been victimized, and facilitating the person’s reconnection with her or his natural social suports, the people who are important in that person’s life. In the immediate aftermath, of course, the first step is always to reestablish some sense of safety in the survivor’s life. That means getting out of physical danger, and that means also creating some sort of minimally safe social environment in which the person has people to count on, to rely on, to connect to. Nobody can recover in isolation.

It’s only after safety is established that it becomes appropriate for this person to have a chance to tell the trauma story in more depth. There we run into two kinds of mistakes. One is the idea that it’s not necessary to tell the story, and that the person would be much better off not talking about it.

DJ: It’s over. Just get on with your life.