by DGR News Service | May 16, 2021 | Alienation & Mental Health, Biodiversity & Habitat Destruction, Building Alternatives, Climate Change, Culture of Resistance, Strategy & Analysis

This article originally appeared on Roarmag.

Editor’s note: Asking questions, questions that emerge from your empathy if you care for life on the planet, and questions that emerge from your confusion if you see that so many things are going so badly wrong, is a very important, crucial step. We completely agree with the last paragraph of this article and our answer is DGR’s Decisive Ecological Warfare strategy.

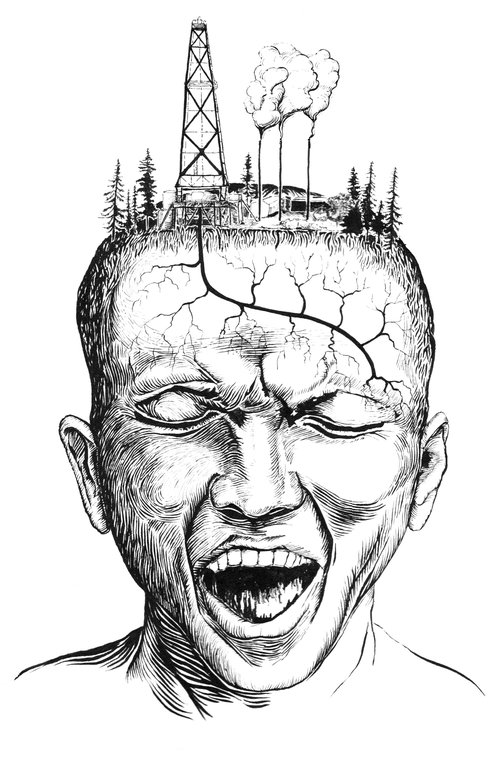

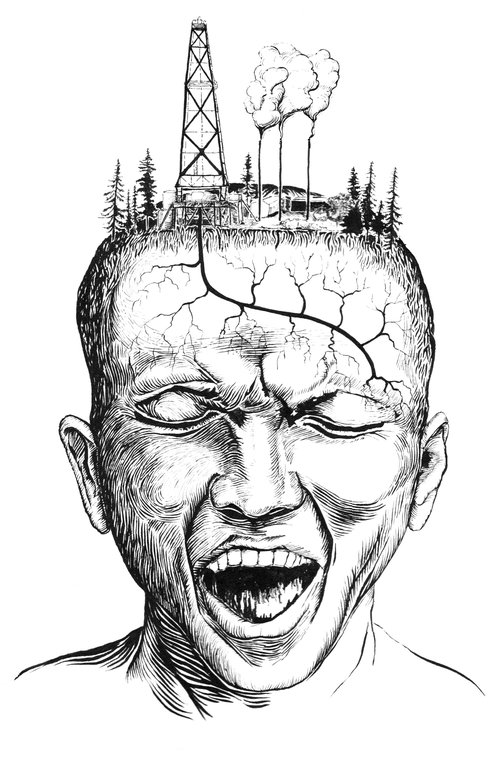

Featured image: “Frack Off” by Nell Parker.

By John Holloway

This is an adapted version of John Holloway’s presentation at the “Crisis of Nation States — Anarchist Answers” conference.

We do not know how to stop the planetary destruction caused by capital — but by asking the right questions we can find our way forward together.

We live in a failed system. It is becoming clearer every day that the present organization of society is a disaster, that capitalism is unable to secure an acceptable way of living. The COVID-19 pandemic is not a natural phenomenon but the result of the social destruction of biodiversity and other pandemics are likely to follow. The global warming that is a threat to both human and many forms of non-human life is the result of the capitalist destruction of established equilibria. The acceptance of money as the dominant measure of social value forces a large part of the world’s population to live in miserable and precarious conditions.

The destruction caused by capitalism is accelerating. Growing inequality, a rise in racist violence, the spread of fascism, increasing tensions between states and the accumulation of power by police and military. Moreover, the survival of capitalism is built on an ever-expanding debt that is doomed to collapse at some point.

The situation is urgent, we humans are now faced with the real possibility of our own extinction.

How do we get out of here? The traditional answer of those who are conscious of the scale of social problems: through the state. Political thinkers and politicians from Hegel to Keynes and Roosevelt and now Biden have seen the state as a counterweight to the destruction wreaked by the economic system. States will solve the problem of global warming; states will end the destruction of biodiversity; states will alleviate the enormous hardship and poverty resulting from the present crisis. Just vote for the right leaders and everything will be all right. And if you are very worried about what is happening, just vote for more radical leaders — Sanders or Corbyn or Die Linke or Podemos or Evo Morales or Maduro or López Obrador — and things will be fine.

The problem with this argument is that experience tells us that it does not work. Left-wing leaders have never fulfilled their promises, have never brought about the changes that they said they would. In Latin America, the left-wing politicians who came to power in the so-called Pink Wave at the start of this century, have been closely associated with extractivism and other forms of destructive development. The Tren Maya which is Mexican president López Obrador’s favorite project in Mexico at the moment is just the latest example of this. Left-wing parties and politicians may be able to bring about minor changes, but they have done nothing at all to break the destructive dynamic of capital.

THE STATE IS NOT THE ANSWER

But it is not just experience that tells us that the state is not the counterweight to capital that some make it out to be. Theoretical reflection tells us the same thing. The state, which appears to be separate from capital, is actually generated by capital and depends on capital for its existence. The state is not a capitalist and its workers do not on the whole generate the income it needs for its existence. That income comes from the exploitation of workers by capital, so that the state actually depends on that exploitation, that is, on the accumulation of capital, to reproduce its own existence.

The state is obliged, by its very form, to promote the accumulation of capital. Capital, too, depends on the existence of an instance — the state — that does not act like a capitalist and that appears to be quite separate from capital, to secure its own reproduction. The state appears to be the center of power, but in fact power lies with the owners of capital, that is, with those persons who dedicate their existence to the expansion of capital. In other words, the state is not a counterweight to capital: it is part of the same uncontrollable dynamic of destruction.

The fact that the state is bound to capital means that it excludes us. State democracy is a process of exclusion that says: “Come and vote every four or five years, then go home and accept what we decide.” The state is the existence of a body of full-time officials who assume the responsibility of ensuring the welfare of society — in a way compatible with the reproduction of capital, of course. By assuming that responsibility, they take it away from us. But, whatever their intentions, they are unable to fulfill the responsibility, because they do not have the countervailing power that they appear to have: what they do and how they do it is shaped by the need to ensure the reproduction of capital.

Just now, for example, politicians are talking of the need for a radical change in political direction as the world emerges from the pandemic, but at no point does any politician or government official suggest that part of that change in direction must be the abolition of a system based on the pursuit of profit.

If the state is not the answer to ending capitalist destruction, then it follows that channeling our concerns into political parties cannot be the answer either, since parties are organizations that aim to bring about change through the state. Attempts to bring about radical change through parties and the taking of state power have generally ended in the creation of authoritarian regimes at least as bad as those they fought to change.

ASKING WE WALK

So, if the state is not the answer, where do we go? How do we get out of here? We come to a conference like this, of course, to discuss anarchist answers. But there are at least three problems: firstly, there are not the millions of people here that we need for a real change of direction; secondly, we have no answers; and thirdly, the label “anarchist” probably does not help.

Why are there not millions of people here? There is certainly a widespread growing feeling of anger, desperation and an awareness that the system is not working. But why is this anger channeled either towards left-reformist parties and candidates (Die Linke, Sanders, Corbyn, Tsipras) or to the far right, and not towards efforts that push against-and-beyond the system? There are many explanations, but one that seems important to me is Leonidas Oikonomakis’ comment on the election of Syriza in Greece in 2015 that, even after years of very militant anti-statist protest against austerity, it still seemed to people that the state was the “only game in town.”

When we think of global warming, of stopping violence against women, of controlling the pandemic, of resolving our economic desperation in the present crisis, it is still hard not to think that the state is where the answers lie, even when we know that it is not.

Perhaps we have to give up the idea of answers. We have no answers. It cannot be a question of opposing anarchist answers to state answers. The state gives answers, wrong answers. We have questions, urgent questions, new questions because this situation of impending extinction has never existed before. How can we stop the destructive dynamic of capital? The only answer that we have is that we do not know.

It is important to say that we do not know, for two reasons. Firstly because it happens to be true. We do not know how we can bring the present catastrophe to an end. We have ideas, but we really do not know. And secondly, because a politics of questions is very different from a politics of answers. If we have the answers, it is our duty to explain them to others. That is what the state does, that is what vanguardist parties do. If we have questions but no answers, then we must discuss them together to try and find ways forward. “Preguntando caminamos,” as the Zapatistas say: “Asking we walk.”

The process of asking and listening is not the way to a different society, it is already the creation of a different society. The asking-listening is already a mutual recognizing of our distinct dignities. We ask-and-listen to you because we recognize your dignity. This is the opposite of state politics. The state talks. It pretends to ask-and-listen but it does not and cannot because its existence depends on reproducing a form of social organization based on the command of money.

Our asking-listening is an anti-identitarian movement. We recognize your dignity not because you are an anarchist or a communist, or German or Austrian or Mexican or Irish, or because you are a woman or Black or Indigenous. Labels are very dangerous — even if they are “nice” labels — because they create identitarian distinctions. To say “we are anarchists” is self-contradictory because it reproduces the identitarian logic of the state: we are anarchists, you are not; we are German, you are not. If we are against the state, then we against its logic, against its grammar.

A MOVEMENT OF SELF-DETERMINATION

We have no answers, but our walking-asking does not start from zero. It is part of a long history of walking-asking. Just in these days we are celebrating the 150th anniversary of the Paris Commune and the centenary of the Kronstadt Uprising. In the present, we have the experience of the Zapatistas to inspire us, just as they are preparing their journey across the Atlantic to connect with the walkers-askers against capital in Europe this summer. And of course we look to the deeply ingrained practice of councilism in the Kurdish movement in the terribly difficult conditions of their struggle. And beyond that, the millions of cracks in which people are trying to organize on an anti-hierarchical, mutually recognitive basis.

It is simply not true that the state is the only game in town. We must shout from the rooftops that there is another, long-established game: the game of doing things ourselves, collectively.

Organization in the communal or council tradition is not on the basis of selection-and-exclusion but on the basis of a coming-together of those who are there, whether in the village or the neighborhood or the factory, with all their differences, their squabbles, their madnesses, their meannesses, their shared interests and common concerns.

The organization is not instrumental: it is not designed as the best way of reaching a goal, for it is itself its own goal. It does not have a defined membership since its aim is to draw in, not to exclude. Its discussions are not aimed at defining the correct line, but at articulating and accommodating differences, at constructing here and now the mutual recognition that is negated by capitalism.

This does not mean a suppression of debate, but, on the contrary, a constant process of discussion and critique aimed not at eliminating or denouncing or labeling the opponent but at maintaining the creative tension that arises from holding together ideas that push in slightly different directions. An always difficult mutual recognizing of dignities that pull in different directions.

The council or commune is a movement of self-determination: through asking-listening-thinking we shall decide how we want the world to be, not by following the blind dictates of money and profit. And, perhaps more and more important, it is an assumption of our responsibility for shaping the future of human life.

If we reach the point of extinction, it will be of no help to say on the last day: “It is all the fault of the capitalists and their states.” No. It will be our fault if we do not break the power of money and take back from the state our responsibility for the future of human life.

John Holloway is a professor of sociology in the Instituto de Ciencias Sociales y Humanidades, Benemérita Universidad Autónoma de Puebla. His books include Change the World without Taking Power (Pluto Press, London, 2002, 2019) and Crack Capitalism (Pluto Press, London, 2010).

by DGR News Service | May 14, 2021 | Biodiversity & Habitat Destruction, Colonialism & Conquest, Culture of Resistance, Defensive Violence, Direct Action, Indigenous Autonomy, Movement Building & Support, People of Color & Anti-racism, Repression at Home, The Problem: Civilization, White Supremacy

Editor’s note: The American Holocaust (a term coined by David Stannard) is the largest genocide in human history. The atrocities are ongoing and being reinforced by fascists like Jair Bolsonaro, providing another example that capitalism and fascism are two sides of the same coin.

Featured image: Indigenous protest, Brazil April 2018. ‘By painting the streets red, we’re showing how much blood has already been shed in the struggle to protect indigenous territories,’ – Sônia Guajajara, a spokeswoman for APIB (Brazilian indigenous organization).

© Marcelo Camargo/Agência Brasil

By Survival International

The land rights of the Xokleng, a tribe that was violently expelled from its territory in the 19th and 20th centuries to make way for European colonists, are now the focus of a landmark court case in Brazil.

The Xokleng were brutally persecuted and evicted by armed militias to make way for European settlers. The Supreme Court hearing into the so-called “Time Limit Trick” could now set the effects of these and subsequent evictions in stone, establishing a precedent which would have far-reaching consequences for indigenous peoples in Brazil.

Other Xokleng communities are also fighting to recover some of their territory. The Xokleng Konglui in Rio Grande do Sul state have launched a ‘retomada’ (reoccupation) of their land, which is now occupied by a national park. The government wants to make it an ‘ecotourism’ destination. © Iami Gerbase/Survival

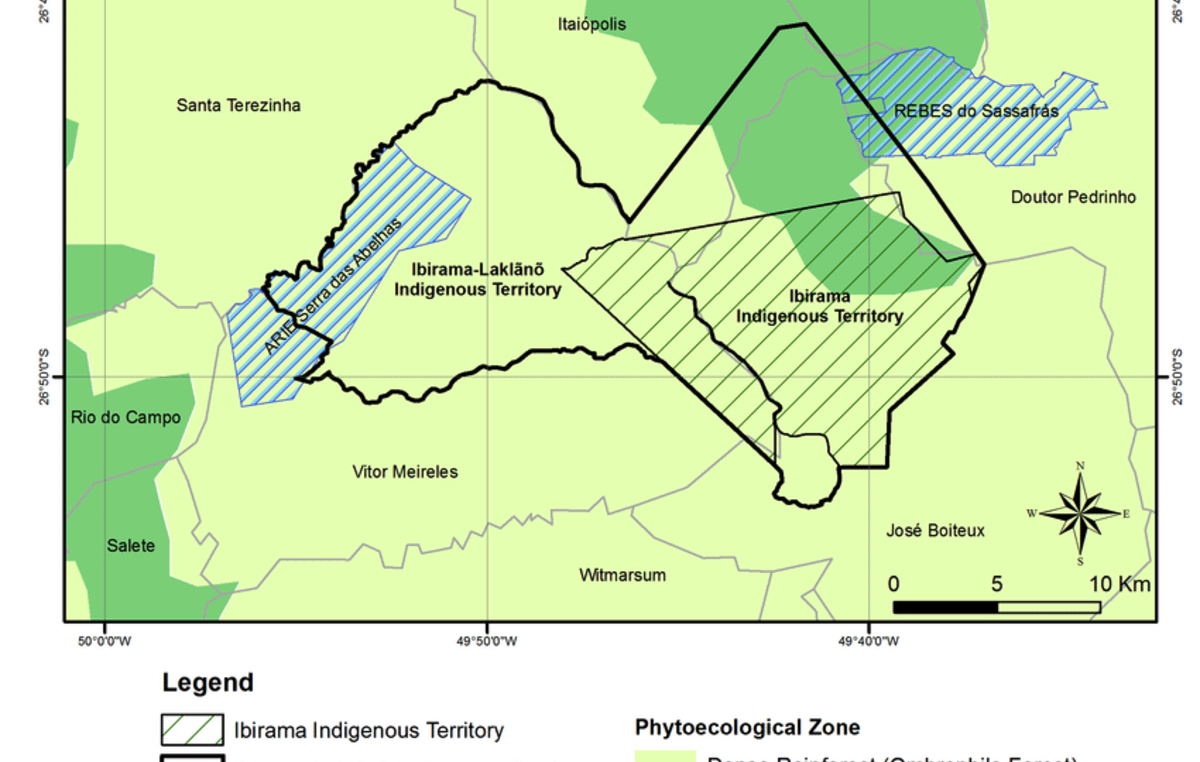

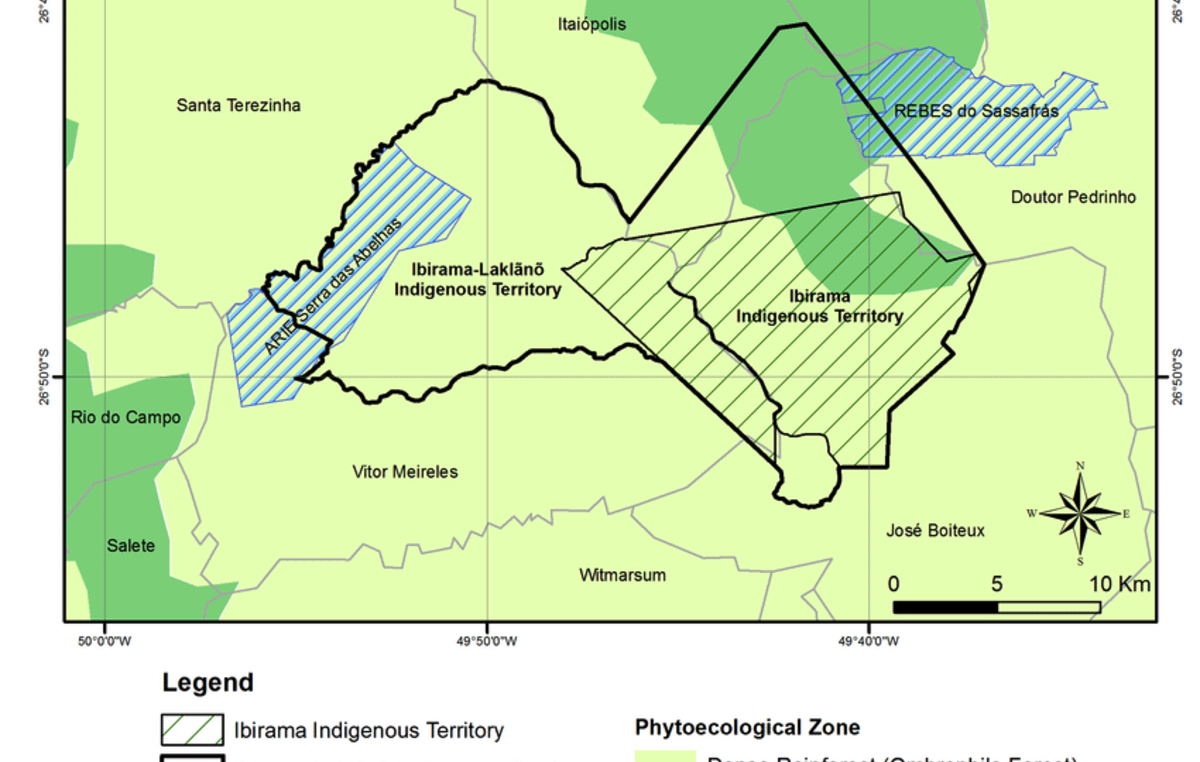

The case centers around the demarcation of the “Ibirama La Klãnõ” Indigenous Territory in the state of Santa Catarina in southern Brazil. If they win, the Xokleng would be able to return to a significant part of their ancestral territory.

However, the official demarcation of the territory has been suspended following a lawsuit filed by non-indigenous residents and a logging company operating in the area. They argue that on October 5, 1988 – the date the Brazilian Constitution was signed – the Xokleng only lived in limited parts of the territory and therefore have no right to most of their original land. If this argument succeeds, it would legitimize centuries of evictions experienced by indigenous peoples throughout Brazil.

The Brazilian government encouraged Europeans to settle on indigenous land, and allocated them large parts of the Xokleng and other indigenous territories at the beginning of the 20th century. It also financed a so-called “Indian-hunting militia”, which accelerated the colonial land grab. This militia specialized in the extermination of indigenous peoples and hunted down the Xokleng.

“The Redskins are interfering with colonization: this interference must be eliminated, and as quickly and thoroughly as possible,” German colonists demanded at the time.

German settlers resented Xokleng attempts to defend their territories, and frequently subjected them to cruel “punitive expeditions.”

The Xokleng territory was continuously reduced over several decades. In the 1970s, a dam was built in the small part that remained.

Map of the current (Ibirama) and planned (Ibirama La Klãnõ) indigenous territory. The expansion of the territory is the cause of the legal dispute. © Marian Ruth Heineberg/Natalia Hanazaki based on data from FUNAI/IBGE/MMA.

If Brazil’s Supreme Court votes in favor of the “Time Limit Trick”, it would have devastating consequences for many other indigenous peoples, and their chances of reclaiming their ancestral territories. It could enable the theft of land that is rightfully owned by hundreds of thousands of tribal and indigenous people. The validity of existing indigenous territories could then also come into question.

Brasílio Priprá, a prominent Xokleng leader, said: “If we didn’t live in a certain part of the territory in 1988, it doesn’t mean it was “no man’s land” or that we didn’t want to be there. The “Time Limit Trick” reinforces the historical violence that continues to leave its mark today.”

Indigenous organizations and their allies, including Survival, began raising fears about the “Time Limit Trick” in 2017, calling it unlawful because it violates the current Brazilian Constitution and international law, which clearly states that indigenous peoples have the right to their ancestral lands.

President Bolsonaro is turning back the clock on indigenous rights, attempting to: erase their right to self-determination; sell off their territories to logging and mining companies; and ‘assimilate’ them against their will. Survival International and tribal peoples are fighting side by side to stop Brazil’s genocide.

Fiona Watson of Survival International said today: “The history of the Xokleng shows just how absurd the “Time Limit Trick” is: Indigenous peoples have been evicted from their lands, hunted down and murdered in Brazil for centuries. Those who demand that in order to have the right to their land now, indigenous lands had to have been inhabited by indigenous communities on October 5, 1988 – after the end of the military dictatorship – are denying this history and perpetuating the genocide in the 21st century.”

Note to the editor:

– More information on the Xokleng and their history can be found here.

– The case before the Court concerns only the Xokleng of Ibirama La Klãnõ indigenous territory. There are many other Xokleng communities.

by DGR News Service | May 13, 2021 | Biodiversity & Habitat Destruction, Strategy & Analysis, The Problem: Civilization, Toxification

The aquatic food web has been seriously compromised by chemical pollution and climate change.

This article originally appeared on Climate and Capitalism

A report released today by the International Pollutants Elimination Network (IPEN) and the National Toxics Network (NTN) says that rising levels of chemical and plastic pollution are major contributors to declines in the world’s fish populations and other aquatic organisms.

Dr. Matt Landos, co-author of the report, says that many people erroneously believe that fish declines are caused only by overfishing. “In fact, the entire aquatic food web has been seriously compromised, with fewer and fewer fish at the top, losses of invertebrates in the sediments and water column, less healthy marine algae, coral, and other habitats, as well as a proliferation of bacteria and toxic algal blooms. Chemical pollution, along with climate change itself a pollution consequence, are the chief reasons for these losses.”

Aquatic Pollutants in Oceans and Fisheries documents the numerous ways in which chemicals compromise reproduction, development, and immune systems among aquatic and marine organisms. It warns that the impacts scientists have identified are only likely to grow in the coming years and will be exacerbated by a changing climate.

As co-author Dr. Mariann Lloyd-Smith points out, the production and use of chemicals have grown exponentially over the past couple of decades. “Many chemicals persist in the environment, making environments more toxic over time. If we do not address this problem, we will face permanent damage to the marine and aquatic environments that have nourished humans and every other life form since the beginning of time.”

The report identifies six key findings:

- Overfishing is not the sole cause of fishery declines. Poorly managed fisheries and catchments have wrought destruction on water quality and critical nursery habitat as well as the reduction and removal of aquatic food resources. Exposures to environmental pollutants are adversely impacting fertility, behavior, and resilience, and negatively influencing the recruitment and survival capacity of aquatic species. There will never be sustainable fisheries until all factors contributing to fishery declines are addressed.

- Chemical pollutants have been impacting oceanic and aquatic food webs for decades and the impacts are worsening. The scientific literature documents man-made pollution in aquatic ecosystems since the 1970s. Estimates indicate up to 80% of marine chemical pollution originates on land and the situation is worsening. Point source management of pollutants has failed to protect aquatic ecosystems from diffuse sources everywhere. Aquaculture is also reaching limits due to pollutant impacts with intensification already driving deterioration in some areas, and contaminants in aquaculture feeds affecting fish health.

- Pollutants including industrial chemicals, pesticides, pharmaceuticals, heavy metals, plastics and microplastics have deleterious impacts to aquatic ecosystems at all trophic levels from plankton to whales. Endocrine disrupting chemicals, which are biologically active at extremely low concentrations, pose a particular long-term threat to fisheries. Persistent pollutants such as mercury, brominated compounds, and plastics biomagnify in the aquatic food web and ultimately reach humans.

- Aquatic ecosystems that sustain fisheries are undergoing fundamental shifts as a result of climate change. Oceans are warming and becoming more acidic with increasing carbon dioxide deposition. Melting sea ice, glaciers and permafrost are increasing sea levels and altering ocean currents, salinity and oxygen levels. Increases in both de-oxygenated ‘dead zones’ and coastal algal blooms are being observed. Furthermore, climate change is re-mobilizing historical contaminants from their ‘polar sinks.’

- Climate change and chronic exposures to pesticides all can amplify the impacts of pollution by increasing exposures, toxicity and bioaccumulation of pollutants in the food web. Methyl mercury and PCBs are among the most prevalent and toxic contaminants in the marine food web.

- We are at the precipice of disaster, but have an opportunity for recovery. Progress requires fundamental shifts in industry, economy and governance, the cessation of deep-sea mining and other destructive industries, and environmentally sound chemical management, and true circular economies. Re-generative approaches to agriculture and aquaculture are urgently required to lower carbon, stop further pollution, and begin the restoration process.

![“May the truth be your armor” [Excerpts from Bright Green Lies]](https://dgrnewsservice.org/wp-content/uploads/sites/18/2021/05/BGL.jpeg)

by DGR News Service | May 11, 2021 | Biodiversity & Habitat Destruction, Climate Change, Education, Listening to the Land, Mining & Drilling, Strategy & Analysis, The Problem: Civilization, Toxification

This prologue is the first of a series of excerpts we will publish from the new book Bright Green Lies.

PROLOGUE

By Lierre Keith

We are in peril. Like all animals, we need a home: a blanket of air, a cradle of soil, and a vast assemblage of creatures who make both. We can’t create oxygen, but others can–from tiny plankton to towering redwoods. We can’t build soil, but the slow circling of bacteria, bison, and sweetgrass do.

But all of these beings are bleeding out, species by species, like Noah and the Ark in reverse, while the carbon swells and the fires burn on. Five decades of environmental activism haven’t stopped this. We haven’t even slowed it. In those same five decades, humans have killed 60 percent of the earth’s animals. And that’s but one wretched number among so many others.

That’s the horror that brings readers to a book like this, with whatever mixture of hope and despair. But we don’t have good news for you. To state it bluntly, something has gone terribly wrong with the environmental movement.

Once, we were the people who defended wild creatures and wild places. We loved our kin, we loved our home, and we fought for our beloved. Collectively, we formed a movement to protect our planet. Along the way, many of us searched for the reasons. Why were humans doing this? What could possibly compel the wanton sadism laying waste to the world? Was it our nature or were only some humans culpable? That analysis is crucial, of course. Without a proper diagnosis, correct treatment is impossible. This book lays out the best answers that we, the authors, have found. We wrote this book because something has happened to our movement. The beings and biomes who were once at the center of our concern have been disappeared. In their place now stands the very system that is destroying them. The goal has been transformed:

We’re supposed to save our way of life, not fight for the living planet; instead, we are to rally behind the “machines making machines making machines” that are devouring what’s left of our home.

Committed activists have brought the emergency of climate change into broad consciousness, and that’s a huge win as the glaciers melt and the tundra burns. But they are solving for the wrong variable. Our way of life doesn’t need to be saved. The planet needs to be saved from our way of life.

There’s a name for members of this rising movement: bright green environmentalists. They believe that technology and design can render industrial civilization sustainable. The mechanism to drive the creation of these new technologies is consumerism. Thus, bright greens “treat consumerism as a salient green practice.”1

Indeed, they “embrace consumerism” as the path to prosperity for all.2 Of course, whatever prosperity we might achieve by consuming is strictly time limited, what with the planet being finite. But the only way to build the bright green narrative is to erase every awareness of the creatures and communities being consumed. They simply don’t matter. What matters is technology. Accept technology as our savior, the bright greens promise, and our current way of life is possible for everyone and forever. With the excised species gone from consciousness, the only problem left for the bright greens to solve is how to power the shiny, new machines.

It doesn’t matter how the magic trick was done. Even the critically endangered have been struck from regard. Now you see them, now you don’t: from the Florida yew (whose home is a single 15-mile stretch, now under threat from biomass production) to the Scottish wildcat (who number a grim 35, all at risk from a proposed wind installation). As if humans can somehow survive on a planet that’s been flayed of its species and bled out to a dead rock. Once we fought for the living. Now we are told to fight for their deaths, as the wind turbines come for the mountains and solar panels conquer the deserts.

“May the truth be your armor” urged Marcus Aurelius. The truths in this book are hard, but you will need them to defend your beloved. The first truth is that our current way of life requires industrial levels of energy. That’s what it takes to fuel the wholesale conversion of living communities into dead commodities. That conversion is the problem “if,” to borrow from Australian anti-nuclear advocate Dr. Helen Caldicott, “you love this planet.” The task before us is not how to continue to fuel that conversion. It’s how to stop it.

The second truth is that fossil fuel–especially oil–is functionally irreplaceable. The proposed alternatives–like solar, wind, hydro, and biomass–will never scale up to power an industrial economy.

Third, those technologies are in their own right assaults against the living world. From beginning to end, they require industrial-scale devastation: open-pit mining, deforestation, soil toxification that’s permanent on anything but a geologic timescale, the extirpation and extinction of vulnerable species, and, oh yes, fossil fuels. These technologies will not save the earth. They will only hasten its demise.

And finally, there are real solutions. Simply put, we have to stop destroying the planet and let natural life come back. There are people everywhere doing exactly that, and nature is responding, some times miraculously. The wounded are healed, the missing reappear, and the exiled return. It’s not too late.

I’m sitting in my meadow, looking for hope. Swathes of purple needlegrass, silent and steady, are swelling with seeds–66 million years of evolution preparing for one more. All I had to do was let the grasses grow back, and a cascade of life followed. The tall grass made a home for rabbits. The rabbits brought the foxes. And now the cry of a fledgling hawk pierces the sky, wild and urgent. I know this cry, and yet I don’t. Me, but not me. The love and the aching distance. What I am sure of is that life wants to live. The hawk’s parents will feed her, teach her, and let her go. She will take her turn–then her children, theirs.

Every stranger who comes here says the same thing: “I’ve never seen so many dragonflies.” They say it in wonder, almost in awe, and always in delight. And there, too, is my hope. Despite everything, people still love this planet and all our kin. They can’t stop themselves. That love is a part of us, as surely as our blood and bones.

Somewhere close by there are mountain lions. I’ve heard a female calling for a mate, her need fierce and absolute. Here, in the last, final scraps of wilderness, life keeps trying. How can I do less?

There’s no time for despair. The mountain lions and the dragonflies, the fledgling hawks and the needlegrass seeds all need us now. We have to take back our movement and defend our beloved. How can we do less? And with all of life on our side, how can we lose?

1. Julie Newman, Green Ethics and Philosophy: An A-to-Z Guide (Thousand Oaks, CA: SAGE Publications, 2011), p. 40.

2. Ibid, p. 39

by DGR News Service | May 9, 2021 | Biodiversity & Habitat Destruction, Colonialism & Conquest, Education, Mining & Drilling, Strategy & Analysis, Toxification

By Straquez

The Colonial Years

Of course, Mexico has been in the front line of atrocities and destruction that come out of mining. Mexico is a land blessed with wide biodiversity that includes minerals that have caught the attention of foreign companies who then act as the machinery to do what this industrial culture does best –converting the living into the dead. High revenue for the company stakeholders, negative benefit for the inhabitants and nothing but endless destruction for the land.

It is said that Aztecs used to embellish and protect their bodies with jewelry, such as necklaces with charms and pedants, armlets, bracelets, leg bracelets, and rings. They would also use tools and vases fabricated with precious metals like gold and silver. These metals were found in deposits located on the surface and not underground like nowadays, this allowed the usage of such mineral resources without much effort or effect.

In 1521, Tenochtitlan, the Aztec capital, was taken over by the Spanish army consolidating Mexico’s Conquest. From then on, mining as an industry started in Mexico as Spaniards started to exploit places where mineral deposits could be located. Mining was carried out mostly in the North and Center of what is now modern day Mexico. Many important mineral deposits started to be discovered in places that later would become famous as they would generate wealth (for whom?) and human settlements. It was only a matter of time before the land subject to mining would be turned into cities such as Guanajuato, San Luis Potosi, Zacatecas, Taxco, Chihuahua and Durango.

Mines kept spreading and mining created many jobs and wealth (I hate to be repetitive, but whose wealth?). Is there even a mention of all the evils done to the indigenous land and people? Not at all, the history of mining is portrayed as progress, as an unquestionable good thing, as a victory and in no terms as a defeat or loss. The whole History of Civilization is pretty much like that, now that I think of it.

After Independence

When the Independence movement of Mexico started in 1810, mining projects were negatively affected and had to be stopped. It was not until 1823 when the movement ended that mining activity was restarted. Remember that I mentioned my surname Straffon being from Cornwall, England? Well, it was precisely during these years that the British Real del Monte Company was established thanks to English capital. This company provided both technology and workforce, some of it straight from Cornwall to re-establish silver mines located in Real del Monte, Hidalgo. 1,500 tons of equipment including 9 steam engines with their large boilers, 5 for pumping, 2 for crushing ore and 2 for use in powering saw mills; various pumps; large cast iron pipes to connect the pumps to be placed at the bottom of the mines with the surface. And so started the rebuilding and modernization of the district’s mining industry. The Cornish miners had brought the Industrial Revolution to Mexico.

By the beginning of the 20th century, Mexico was entering a major political transformation as new laws and codes were created. During Porfirio Diaz’ administration, for example, most of the railroad infrastructure was built all through the country, focusing on the main mining centers that were already established. Then the American corporations showed up offering the means for better extraction as mines during the times of Nueva España were certainly used, but could not be exploited to their maximum because Spain lacked the technology and resources to do so.

The Fresnillo Company, Mazapil Cooper Co., Peñoles Mining Co., and Pittsburg & Mexico Tin Mining Co. were some of the companies looking to make a profit out of Mexico’s mines. Parallel industries started to rise, the economy diversified and the country’s elite dreamed of Mexico being on its way to becoming a world economy. Metallurgical processes were improved with maximum return on capital and mineral processing efficiency as the main goal. The bonanza would cease somewhat in the 1960s when the mining industry was nationalized and mine administration passed to the charge of Mexican professionals.

Then came NAFTA, and in 1992 mining laws were modified substantially in order to accommodate the demands of big national and transnational corporations. Compared to the prior 300 years, production of gold and silver doubled even though several communities resisted the exploitation. Social and environmental damage increased substantially as a consequence due to legal impunity and the ability of the mining organizations to trample over human rights. The Mexican Mining Law of 1992 is a unique and unconstitutional piece of legislation, and rides roughshod over earlier laws which allowed for judicial challenges and which consequently made it difficult for companies to carry on their business with impunity. The solution of the mining organizations was, of course, to create a whole web of corruption that extends to the three branches of government. We are still living the influence of NAFTA until this very day. Business as usual.

Keep on Digging

Doctor María Teresa Sánchez Salazar has set out very interesting mine “conflict maps” which consider many parameters including land conflict, environmental conflict, social conflict, labor conflict or a combination of those factors. Data shows that 75% of these conflicts have to do with land, that is, land grabs by the mining companies or due to environmental conflicts, and almost 70% of them happen in open-pit mines. Another interesting number – 60% of the conflicts have involved foreign company owned mines.

She adds that there are places where conflict started due to land grab and the subsequent leasing to mining companies and the implementation of ways to displace people from their native lands. Of a total of 181 natural areas, 57 have been leased for mining. Eight of them focus more than 75% of the surface to this activity. Twenty of them have at least 93% of their surface leased. One example is the Rayón National Park in Michoacan, its land is practically 100% leased for mining as well as Huautla Mountain Range that is between Morelos, Puebla and Guerrero.

Safety is also an issue for the Mexican mining sector. There are powerful cartels that have quite an influence in the entire country, including mining states such as Sonora, Chihuahua, Sinaloa and Guerrero. Mines have been object of many armed robberies that have increased during the COVID-19 pandemic. Extortion, threats and employee kidnapping have been the most common crimes reported by the mining companies.

If this was a Robin Hood kind of deal then I should certainly support it, but in the end workers are the most affected, operations are seldom slowed down and the exploitation just does not stop. If the criminal gangs were to take over, not much would change as, let’s be honest, both companies and cartels pretty much operate the same way but at a different scale.

Bacadéhuachi

In times prior to the year 1600, this area was inhabited by Opata indigenous settlements. In the year 1645 a mission named San Luis Gonzága de Bacadéhuachi was founded by the Jesuit missionary Cristóbal García. Its current inhabitants dedicate their lives to taking care of livestock and making cheese, bread and tortillas which are sold among themselves; within the world economy, they don’t have much of a choice. Being only 270 kilometers away from Hermosillo, capital of the State of Sonora, the road takes 5 hours to transit due to the uneven and complex terrain that in turn makes it a dangerous travel.

This town is on the same route of the high mountain range that takes you to Chihuahua, its neighbor state. This is a high-risk road as armed conflicts are constantly raging between groups that are looking to take control of this area. Some months ago, armed men went into the municipality creating such a situation and ending the peaceful environment to the point that the Mexican National Guard and the State Police now have to be constantly present.

Bacadehuachi has around 500 houses, most of them made of adobe, occupied by around 1,083 people according to the The National Institute of Statistics and Geography (INEGI). It has cobblestone roads and few are made of concrete due to the minimal vehicle transit. It is more common to see people on horses or donkeys than in motor vehicles. Everything is around the corner, there are no gas stations nearby. It has 3 municipal police officers that issue around 10 different fines a year. There is only one health center for basic checkups and a doctor is available every 3 days.

Regarding education, only one preschool, one primary school and one secondary school exist. For those who want to receive higher education, their only choice is to go to Granados, a municipality 50 kilometers away from the town. The road is risky to say the least, young students must stay at the neighboring town and go back to their families at the weekends in a municipality sponsored bus. To go to college is a victory, a luxury, a rare occurrence for the townspeople.

Don’t Know What I’m Selling

Miguel Teran is a farmer and former owner of La Ventana ranch. He sold his land to Bacanora Lithium for the Sonora Lithium Project. He asserts that the first explorations started back in 1994. Geologists came to the La Ventana ranch in government cars. They took some soil samples, came back 8 years later, measured the land and after that they never came back. Ten years ago, Bacanora Lithium carried out some studies. They drilled around 115 holes with the permission of Miguel and then they offered to buy the land.

I told them: you know what you’re buying, but I don’t know what I’m selling. Don’t take advantage of me. That’s how the negotiation started, but they wanted to pay as if it was a mere piece of land.”

Miguel wasn’t disappointed yet he acknowledges that he could have made a better deal as he has since found out what treasure lies in the 1,900 hectares that were sold and integrated into the Sonora Lithium Project. For the time being and until the mineral is extracted, Miguel may allow his cows to graze there as stipulated in the contract.

I am within my rights until I get in the way, but I have already bought some land.” Finally, he adds, “sometimes my car battery would fail and they would tell me that I had lithium here, but I only know about horses and chickens; not lithium.”

The Trauma of Our Technological Selves

As a city-dweller, my experience with Nature has been for the most part parks and decorative gardens. Since I live so disconnected from the land itself, I can only enter into relationship with my own species, our creations and the animals we call pets. For a long time I’ve been scared of insects and even though working in a garden has helped diminish the feeling, I still feel uncomfortable in certain scenarios. Soil and its minerals are even weirder to me, because I had never considered them something other than a resource, a component that can be used for my benefit through technology. They don’t seem alive, they don’t seem to have any other purpose than sitting there for us to transform them into something else.

Perhaps my biggest realization during my journey to connect with the land is the enormous damage that Capitalism, Colonialism and Industrialism have inflicted on the planet. It has reached the point that we are also physically, psychologically, emotionally and spiritually bent and broken enough for us to barely notice the indifference and violence around us. Indifference and violence done to each other and to ourselves. And yet, those who notice don’t always take action. Even less, those who know and take action don’t have a clear idea, much less a strategy to stop the abuse.

This is not something that modern technology can fix. Not the electric cars, not the solar cells nor the electric batteries. Not the tote bags and the bamboo toothbrushes that you can use as compost. Our home is being gutted and we just stand there watching, unsure on what to do. When you actually want to stop a killer, you go ahead and do it. You don’t offer knives from recycled metal or whips made out of hemp. You go ahead and put an end to the abuse by neutralizing any capacity to inflict damage that the perpetrator might have. You stop the killing, you stop the behavior, you commit yourself to do so.

Today I read that only 3% of world’s ecosystems remain intact. Civilization is going down regardless of what we do. Nothing can grow indefinitely without collapsing. The real question is what will be left when our civilization goes down. Our struggle resides in stopping it before there is nothing left.

Cristopher Straffon Marquez a.k.a. Straquez is a theater actor and language teacher currently residing in Tijuana, Baja California, Mexico. Artist by chance and educator by conviction, Straquez was part of the Zeitgeist Movement and Occupy Tijuana Movement growing disappointed by good intentions misled through dubious actions. He then focused on his art and craft as well as briefly participating with The Living Theatre until he stumbled upon Derrick Jensen’s Endgame and consequently with the Deep Green Resistance: Strategy to Save the Planet both changing his mind, heart and soul. Since then, reconnecting with the land, decolonizing the mind and fighting for a living planet have become his goals.

by DGR News Service | May 8, 2021 | Biodiversity & Habitat Destruction, Colonialism & Conquest, Education, Mining & Drilling, Strategy & Analysis, Toxification

By Straquez

Mine is the Ignorance of the Many

I was born in Mexico City surrounded by big buildings, a lot of cars and one of the most contaminated environments in the world. When I was 9 years old my family moved to Tijuana in North West Mexico and from this vantage point, on the wrong side of the most famous border town in the world, I became acquainted with American culture. I grew up under the American way of life, meaning in a third-world city ridden with poverty, corruption, drug trafficking, prostitution, industry and an immense hate for foreigners from the South.

Through my school years, I probably heard a couple of times how minerals are acquired and how mining has brought “prosperity” and “progress” to humanity. I mean, even my family name comes from Cornwall, known for its mining sites. The first Straffon to arrive from England to Mexico did so around 1826 in Real del Monte in the State of Hidalgo (another mining town!). However, it is only recently, since I have started following the wonderful work being done in Thacker Pass by Max Wilbert and Will Falk that the horrors of mining came into focus and perspective.

What is mining? You smash a hole in the ground, go down the hole and smash some more then collect the rocks that have been exposed and process them to make jewelry, medicines or technology. Sounds harmless enough. It’s underground and provides work and stuff we need, right? What ill could come out of it? After doing some digging (excuse the pun), I feel ashamed of my terrible ignorance. Mine is the ignorance of the many. This ignorance is more easily perpetuated in a city where all the vile actions are done just so we can have our precious electronics, vehicles and luxuries.

Mine Inc.

Mining, simply put, is the extraction of minerals, metals or other geological materials from earth including the oceans. Mining is required to obtain any material that cannot be grown or artificially created in a laboratory or factory through agricultural processes. These materials are usually found in deposits of ore, lode, vein, seam, reef or placer mining which is usually done in river beds or on beaches with the goal of separating precious metals out of the sand. Ores extracted through mining include metals, coal, oil shale, gemstones, calcareous stone, chalk, rock salt, potash, gravel, and clay. Mining in a wider sense means extraction of any resource such as petroleum, natural gas, or even water.

Mining is one of the most destructive practices done to the environment as well as one of the main causes of deforestation. In order to mine, the land has to be cleared of trees, vegetation and in consequence all living organisms that depend on them to survive are either displaced or killed. Once the ground is completely bare, bulldozers and excavators are used to smash the integrity of the land and soil to extract the metals and minerals.

Mining comes in different forms such as open-pit mining. Like the name suggests, is a type of mining operation that involves the digging of an open pit as a means of gaining access to a desired material. This is a type of surface mining that involves the extraction of minerals and other materials that are conveniently located in close proximity to the surface of the mining site. An open pit mine is typically excavated with a series of benches to reach greater depths.

Open-pit mining initially involves the removal of soil and rock on top of the ore via drilling or blasting, which is put aside for future reclamation purposes after the useful content of the mine has been extracted. The resulting broken up rock materials are removed with front-end loaders and loaded onto dump trucks, which then transport the ore to a milling facility. The landscape itself becomes something out of a gnarly science-fiction movie.

Once extracted, the components are separated by using chemicals like mercury, methyl-mercury and cyanide which of course are toxic to say the least. These chemicals are often discharged into the closest water sources available –streams, rivers, bays and the seas. Of course, this causes severe contamination that in turn affects all the living organisms that inhabit these bodies of water. As much as we like to distinguish ourselves from our wild kin this too affects us tremendously, specially people who depend on the fish as their staple food or as a livelihood.

One of the chemical elements that is so in demand in our current economy is Lithium. Lithium battery production today accounts for about 40% of lithium mining and 25% of cobalt mining. In an all-battery future, global mining would have to expand by more than 200% for copper, by a minimum of 500% for lithium, graphite, and rare earths, and far more for cobalt.

Lithium – Isn’t that a Nirvana song?

Lithium is the lightest metal known and it is used in the manufacture of aircraft, nuclear industry and batteries for computers, cellphones, electric cars, energy storage and even pottery. It also can level your mood in the form of lithium carbonate. It has medical uses and helps in stabilizing excessive mood swings and is thus used as a treatment of bipolar disorder. Between 2014 and 2018, lithium prices skyrocketed 156% . From 6,689 dollars per ton to a historic high of 17,000 dollars in 2018. Although the market has been impacted due to the on-going pandemic, the price of lithium is also rising rapidly with spodumene (lithium ore) at $600 a ton, up 40% on last year’s average price and said by Goldman Sachs to be heading for $676/t next year and then up to $707/t in 2023.

Lithium hydroxide, one of the chemical forms of the metal preferred by battery makers, is trading around $11,250/t, up 13% on last year’s average of $9978/t but said by Goldman Sachs to be heading for $12,274 by the end of the year and then up to $15,000/t in 2023. Lithium is one of the most wanted materials for the electric vehicle industry along cobalt and nickel. Demand will only keep increasing if battery prices can be maintained at a low price.

Simply look at Tesla’s gigafactory in the Nevada desert which produces 13 million individual cells per day. A typical Electronic Vehicle battery cell has perhaps a couple of grams of lithium in it. That’s about one-half teaspoon of sugar. A typical EV can have about 5,000 battery cells. Building from there, a single EV has roughly 10 kilograms—or 22 pounds—of lithium in it. A ton of lithium metal is enough to build about 90 electric cars. When all is said and done, building a million cars requires about 60,000 tons of lithium carbonate equivalent (LCE). Hitting 30% penetration is roughly 30 million cars, works out to about 1.8 million tons of LCE, or 5 times the size of the total lithium mining industry in 2019.

Considering that The United States-Mexico-Canada Agreement (USMCA) is being negotiated, lithium exploitation is a priority as a “must be secured” supply chain resource for the North American corporate machine. In 3 years, cars fabricated in these three countries must have at least 75% of its components produced in the North American region so they can be duty-free. This includes the production of lithium batteries that could also become a profitable business in Mexico.

Sonora on Lithium

In the mythical Sierra Madre Occidental (“Western Mother” Mountain Range) which extends South of the United States, there is a small town known as Bacadéhuachi. This town is approximately 11 km away from one of the biggest lithium deposits in the world known as La Ventana. At the end of 2019, the Mexican Government confirmed the existence of such a deposit and announced that a concession was already granted on a joint venture project between Bacanora Minerals (a Canadian company) and Gangfeng Lithium (a Chinese company) to extract the coveted mineral. The news spread and lots of media outlets and politicians started to refer to lithium as “the oil of the future.”

I quote directly the from Bacanora Lithium website:

Sonora Lithium Ltd (“SLL”) is the operational holding company for the Sonora Lithium Project and owns 100% of the La Ventana concession. The La Ventana concession accounts for 88% of the mined ore feed in the Sonora Feasibility Study which covers the initial 19 years of the project mine life. SLL is owned 77.5% by Bacanora and 22.5% by Ganfeng Lithium Ltd.

Sonora holds one of the world’s largest lithium resources and benefits from being both high grade and scalable. The polylithionite mineralisation is hosted within shallow dipping sequences, outcropping on surface. A Mineral Resource estimate was prepared by SRK Consulting (UK) Limited (‘SRK’) in accordance with NI 43-101.”

The Sonora Lithium Project is being developed as an open-pit strip mine with operation planned in two stages. Stage 1 will last for four years with an annual production capacity of approximately 17,500t of lithium carbonate, while stage 2 will ramp up the production to 35,000 tonnes per annum (tpa). The mining project is also designed to produce up to 28,800 tpa of potassium sulfate (K2SO4), for sale to the fertilizer industry.

On September 1st, 2020, Mexico’s President, Andres Manuel Lopez Obrador, dissolved the Under-secretariat of Mining as part of his administration’s austerity measures. This is a red flag to environmental protection as it creates a judicial void which foreign companies will use to allow them greater freedom to exploit more and safeguard less as part of their mining concession agreements.

Without a sub-secretariat, mediation between companies, communities and environmental regulations is virtually non-existent. Even though exploitation of this particular deposit had been adjudicated a decade ago under Felipe Calderon’s administration, the Mexican state is since then limited to monitoring this project. This lack of regulatory enforcement will catch the attention of investors and politicians who will use the situation to create a brighter, more profitable future for themselves and their stakeholders.

To my mind there is a bigger question – how will Mexico benefit from having one of the biggest deposits of lithium in the world? Taking into account the dissolution of the Mining sub-secretariat and the way business and politics are usually handled in Mexico, I do wonder who will be the real beneficiaries of the aforementioned project.

Extra Activism

Do not forget, mining is an integral part of our capitalist economy; mining is a money making business – both in itself and as a supplier of materials to power our industrial civilization. Minerals and metals are very valuable commodities. Not only do the stakeholders of mining companies make money, but governments also make money from revenues.

There was a spillage in the Sonora river in 2014. It affected over 22,000 people as 40 million liters of copper sulfate were poured into its waters by the Grupo Mexico mining group. Why did this happen? Mining companies are run for the profit of its stakeholder and it was more profitable to dump poison into the river than to find a way to dispose it with a lower environmental impact. Happily for the company stakeholders, company profit was not affected in the least.

Even though the federal Health Secretariat in conjunction with Grupo México announced in 2015 the construction of a 279-million-peso (US $15.6-million) medical clinic and environmental monitoring facility to be known as the Epidemiological and Environmental Vigilance Unit (Uveas) to treat and monitor victims of the contamination, until this day it has not been completed. The government turned a blind eye to the incident after claiming they would help. All the living beings near the river are still suffering the consequences.

Mining is mass extraction and this takes us to the practice of “extractivism” which is the destruction of living communities (now called “resources”) to produce stuff to sell on the world market – converting the living into the dead. While it does include mining – extraction of fossil fuels and minerals below the ground, extractivism goes beyond that and includes fracking, deforestation, agro-industry and megadams.

If you look at history, these practices have deeply affected the communities that have been unlucky enough to experience them, especially indigenous communities, to the advantage of the so-called rich. Extractivism is connected to colonialism and neo-colonialism; just look at the list of mining companies that are from other countries – historically companies are from the Global North. Regardless of their origins, it always ends the same, the rich colonizing the land of the poor. Indigenous communities are disproportionately targeted for extractivism as the minerals are conveniently placed under their land.

While companies may seek the state’s permission, even work with them to share the profits, they often do not obtain informed consent from communities before they begin extracting – moreover stealing – their “resources”. The profit made rarely gets to the affected communities whose land, water sources and labor is often being used. As an example of all of this, we have the In Defense of the Mountain Range movement in Coatepec, Veracruz. Communities are often displaced, left with physical, mental and spiritual ill health, and often experience difficulties continuing with traditional livelihoods of farming and fishing due to the destruction or contamination of the environment.

Cristopher Straffon Marquez a.k.a. Straquez is a theater actor and language teacher currently residing in Tijuana, Baja California, Mexico. Artist by chance and educator by conviction, Straquez was part of the Zeitgeist Movement and Occupy Tijuana Movement growing disappointed by good intentions misled through dubious actions. He then focused on his art and craft as well as briefly participating with The Living Theatre until he stumbled upon Derrick Jensen’s Endgame and consequently with the Deep Green Resistance: Strategy to Save the Planet both changing his mind, heart and soul. Since then, reconnecting with the land, decolonizing the mind and fighting for a living planet have become his goals.

![“May the truth be your armor” [Excerpts from Bright Green Lies]](https://dgrnewsservice.org/wp-content/uploads/sites/18/2021/05/BGL.jpeg)