The concept of the “technosphere” aims to reveal the immense scale of our collective impact. The concept was first introduced by US geologist Peter Haff in 2013, but paleobiologist Jan Zalasiewicz has since popularised the term through his work. The technosphere encompasses the vast global output of materials generated by human activities, as well as the associated energy consumption.

Since the agricultural revolution some 12,000 years ago (when we started building cities and accumulating goods), human enterprise has steadily grown. However, our impact has surged dramatically over the past couple of centuries. This surge has since transformed into exponential growth, particularly since 1950.

The technosphere is indicative of how humans are increasingly emerging as a global force on par with the natural systems that shape the world. The transformation that is needed to reduce our impact is therefore equally large. And yet, despite growing awareness, there has been a lack of concrete action to address humanity’s impact on the planet.

To comprehend the sheer magnitude of the technosphere, it is best visualised. So here are four graphs that capture how our collective addiction to “stuff” is progressively clogging up planet Earth.

1. Weighing the technosphere

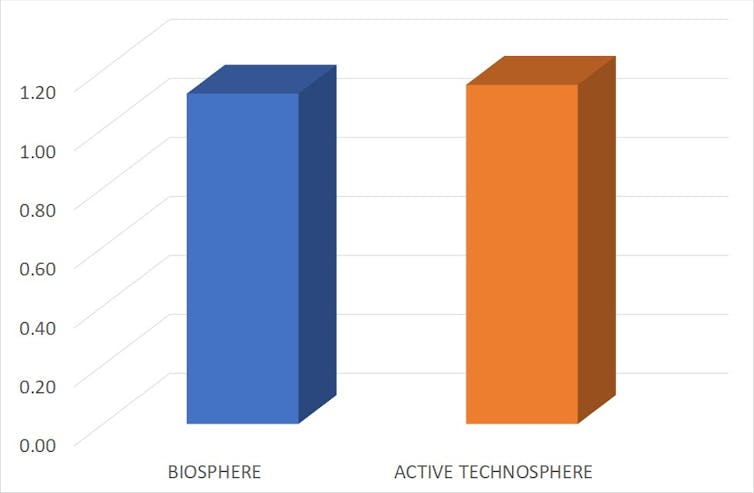

In 2020, a group of Israeli academics presented a shocking fact: the combined mass of all materials currently utilised by humanity had surpassed the total mass of all living organisms on Earth.

According to their findings, the collective weight of all life on Earth (the biosphere) – ranging from microbes in the soil, to trees and animals on land – stands at 1.12 trillion tonnes. While the mass of materials actively used by humans, including concrete, plastic and asphalt, weighed in at 1.15 trillion tonnes.

The technosphere weighs more than all life on Earth (trillion tonnes):

The relative weights of the active technosphere and biosphere. The active technosphere includes materials that are currently in use by human activities. The biosphere includes all living things.

The relative weights of the active technosphere and biosphere. The active technosphere includes materials that are currently in use by human activities. The biosphere includes all living things.

Elhacham et al. (2020), CC BY-NC-ND

This graph offers a glimpse into the immense size of humanity’s footprint. But it likely only scratches the surface.

When accounting for the associated byproducts of the materials used by humans, including waste, ploughed soil and greenhouse gases, the geologist and palaeontologist, Jan Zalasiewicz, calculated that the technosphere expands to a staggering 30 trillion tonnes. This would include a mass of industrially emitted carbon dioxide equivalent to 150,000 Egyptian Pyramids.

2. Changing the Earth

Remarkably, human activity now dwarfs natural processes in changing the surface of our planet. The total global sediment load (erosion) that is transported naturally each year, primarily carried by rivers flowing into ocean basins, is estimated to be around 30 billion tonnes on average. However, this natural process has been overshadowed by the mass of material moved through human action like construction and mining activities.

In fact, the mass of material moved by humans surpassed the natural sediment load in the 1990s and has since grown rapidly. In 2015 alone, humans moved approximately 316 billion tonnes of material – more than ten times the natural sediment load.

Humans change the Earth’s surface more than natural processes (billion tonnes):

Global movement of material: average annual natural sediment transport (blue), the total mass of things transported by humans in 1994 (purple) and in 2015 (orange).

Global movement of material: average annual natural sediment transport (blue), the total mass of things transported by humans in 1994 (purple) and in 2015 (orange).

Cooper at al. (2018) & ScienceDaily (2004), CC BY-NC-ND

3. Transporting ‘stuff’

Our ability to transport fuel and products worldwide has facilitated the trends shown in the preceding graphs. Humans now transport these materials over increasingly vast distances.

Shipping continues to be the primary mechanism for moving materials around the globe. Since 1990, the amount of materials that are shipped around the world has increased more than threefold – and is continuing to grow.

How shipping has grown since 1980 (million tonnes):

Shipping capacity growth between 1980 and 2022.

Shipping capacity growth between 1980 and 2022.

World Ocean Review (2010) & UNCTAD (2022), CC BY-NC-ND

4. The growth of plastics

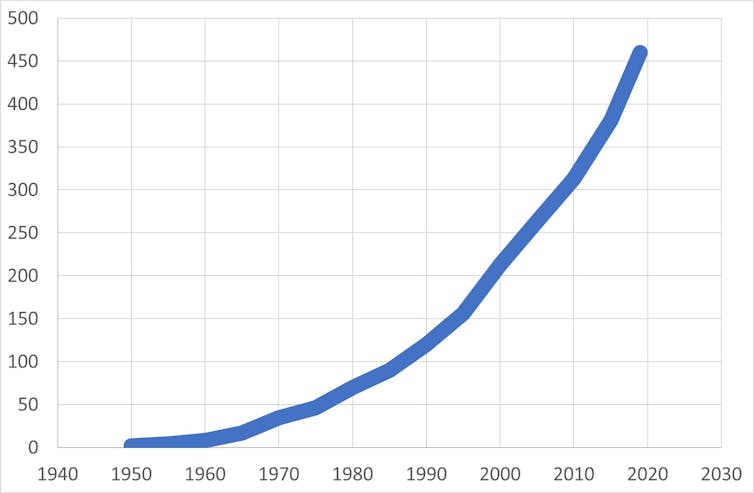

Plastic stands out as one of the main “wonder materials” of the modern world. Due to the sheer speed and scale of the growth in plastic manufacturing and use, plastic is perhaps the metric most representative of the technosphere.

The first forms of plastic emerged in the early 20th century. But its mass production began following the second world war, with an estimated quantity of 2 million tonnes produced in 1950. However, the global production of plastic had increased to approximately 460 million tonnes by 2019.

This surge in plastic manufacturing is a pressing concern. Plastic pollution now causes many negative impacts on both nature and humans. Ocean plastics, for example, can degrade into smaller pieces and be ingested by marine animals.

Plastic manufacturing (million tonnes) has grown exponentially since 1950:

Annual plastic production.

Annual plastic production.

Geyer et al. (2017) and OECD (2023), CC BY-NC-ND

Humanity’s escalating impact on planet Earth poses a significant threat to the health and security of people and societies worldwide. But understanding the size of our impact is only one part of the story.

Equally important is the nature, form and location of the different materials that constitute the technosphere. Only then can we understand humanity’s true impact. For example, even the tiniest materials produced by humans, such as nanoplastics, can have significant and far-reaching consequences.

What is clear, though, is that our relentless pursuit of ever-increasing material output is overwhelming our planet.![]()

Aled Jones, Professor & Director, Global Sustainability Institute, Anglia Ruskin University and Nick King, Visiting Researcher, Anglia Ruskin University

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.

Map of orange stream observations across Arctic Inventory and Monitoring Network (ARCN) parks in northern Alaska. Picture inserts show aerial images of select iron-impacted, orange streams. Map created by Carson Baughman, U.S. Geological Survey. Photos by Kenneth Hill, National Park Service. Public domain.

Map of orange stream observations across Arctic Inventory and Monitoring Network (ARCN) parks in northern Alaska. Picture inserts show aerial images of select iron-impacted, orange streams. Map created by Carson Baughman, U.S. Geological Survey. Photos by Kenneth Hill, National Park Service. Public domain. Impacts of iron mobilization in a stream tributary of the Akillik River located in Kobuk Valley National Park, Alaska. These images were taken two years apart. The clear picture was taken in June 2016 and the orange picture was August 2018. Photos by Jon O’Donnell, National Park Service.

Impacts of iron mobilization in a stream tributary of the Akillik River located in Kobuk Valley National Park, Alaska. These images were taken two years apart. The clear picture was taken in June 2016 and the orange picture was August 2018. Photos by Jon O’Donnell, National Park Service.