by DGR News Service | Sep 18, 2021 | Agriculture, Repression at Home, Strategy & Analysis, Worker Exploitation

This article originally appeared in Climate & Capitalism.

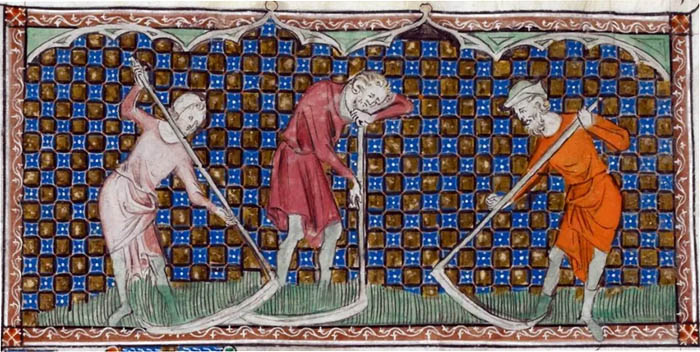

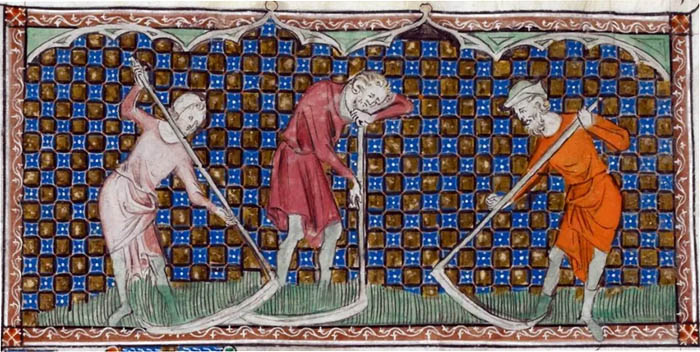

Featured image: Harvesting grain in the 1400s

Editor’s note: We are no Marxists, but we find it important to look at history from the perspective of the usual people, the peasants, and the poor, since liberal historians tend to follow the narrative of endless progress and neglect all the violence and injustice this “progress” was and is based on. Garrett Hardin’s annoying but very influential essay “The Tragedy of the Commons” is a good example, and we are thankful to the author for debunking it.

“All progress in capitalist agriculture is a progress in the art, not only of robbing the worker, but of robbing the soil.” (Karl Marx)

Articles in this series:

Commons and classes before capitalism

‘Systematic theft of communal property’

Against Enclosure: The Commonwealth Men

Dispossessed: Origins of the Working Class

Against Enclosure: The Commoners Fight Back

by Ian Angus

To live, humans must eat, and more than 90% of our food comes directly or indirectly from soil. As philosopher Wendell Berry says, “The soil is the great connector of lives…. Without proper care for it we can have no community, because without proper care for it we can have no life.”[1]

Preventing soil degradation and preserving soil fertility ought to be a global priority, but it isn’t. According to the United Nations, a third of the world’s land is now severely degraded, and we lose 24 billion tonnes of fertile soil every year. More than 1.3 billion people depend on food from degraded or degrading agricultural land.[2] Even in the richest countries, almost all food production depends on massive applications of synthetic fertilizers and pesticides that further degrade the soil and poison the environment.

In Karl Marx’s words, “a rational agriculture is incompatible with the capitalist system.”[3] To understand why that is, we need to understand how capitalist agriculture emerged from a very different system.

****

For almost all of human history, almost all of us lived and worked on the land. Today, most of us live in cities.

It is hard to overstate how radical that change is, or how quickly it happened. Two hundred years ago, 90% of the world’s population was rural. Britain became the world’s first majority-urban country in 1851. As recently as 1960, two-thirds of the world’s people still lived in rural areas. Now it’s less than half, and only half of those are farmers.

Between the decline of feudalism and the rise of industrial capitalism, rural society was transformed by the complex of processes that are collectively known as enclosure. The separation of most people from the land, and the concentration of land ownership in the hands of a tiny minority, were revolutionary changes in the ways that humans lived and work. It happened in different ways and at different times in different parts of the world, and is still going on today.

Our starting point is England, where what Marx labelled “so-called primitive accumulation” first occurred.

Common Fields, Common Rights

In medieval and early-modern England, most people were poor, but they were also self-provisioning — they obtained their essential needs directly from the land, which was a common resource, not private property as we understand the concept.

No one actually knows when or how English common farming systems began. Most likely they were brought to England by Anglo-Saxon settlers after Roman rule ended. What we know for sure is that common field agriculture was widespread, in various forms, when English feudalism was at its peak in the twelfth and thirteenth centuries.

The land itself was held by landlords, directly or indirectly from the king. A minor gentry family might hold and live on just one manor — roughly equivalent to a township — while a top aristocrat, bishop or monastery could hold dozens. The people who actually worked the land, often including a mix of unfree serfs and free peasants, paid rent and other fees in labor, produce or (later) cash, and had, in addition to the use of arable land, a variety of legal and traditional rights to use the manor’s resources, such as grazing animals on common pasture, gathering firewood, berries and nuts in the manor forest, and collecting (gleaning) grain that remained in the fields after harvest.

“Common rights were managed, divided, and redivided by the communities. These rights were predicated on maintaining relations and activities that contributed to the collective reproduction. No feudal lord had rights to the land exclusive of such customary rights of the commoners. Nor did they have the right to seize or engross the common fields as their own domain.”[4]

Field systems varied a great deal, but usually a manor or township included both the landlord’s farm (demesne) and land that was farmed by tenants who had life-long rights to use it. Most accounts only discuss open field systems, in which each tenant cultivated multiple strips of land that were scattered through the arable fields so no one family had all the best soil, but there were other arrangements. In parts of southwestern England and Scotland, for example, farms on common arable land were often compact, not in strips, and were periodically redistributed among members of the commons community. This was called runrig; a similar arrangement in Ireland was called rundale.

Most manors also had shared pasture for feeding cattle, sheep and other animals, and in some cases forest, wetlands and waterways.

Though cooperative, these were not communities of equals. Originally, all of the holdings may have been about the same size but in time considerable economic differentiation took place.[5] A few well-to-do tenants held land that produced enough to sell in local markets; others (probably a majority in most villages) had enough land to sustain their families with a small surplus in good years; others with much less land probably worked part-time for their better-off neighbors or for the landlord. “We can see this stratification right across the English counties in Domesday Book of 1086, where at least one-third of the peasant population were smallholders. By the end of the thirteenth century this proportion, in parts of southeastern England, was over a half.”[6]

As Marxist historian Rodney Hilton explains, the economic differences among medieval peasants were not yet class differences. “Poor smallholders and richer peasants were, in spite of the differences in their incomes, still part of the same social group, with a similar style of life, and differed from one to the other in the abundance rather than the quality of their possessions.”[7] It wasn’t until after the dissolution of feudalism in the fifteenth century that a layer of capitalist farmers developed.

Self-Management

If we were to believe an influential article published in 1968, commons-based agriculture ought to have disappeared shortly after it was born. In “The Tragedy of the Commons,” Garrett Hardin argued that commoners would inevitably overuse resources, causing ecological collapse. In particular, in order to maximize his income, “each herdsman will try to keep as many cattle as possible on the commons,” until overgrazing destroys the pasture, and it supports no animals at all. “Freedom in a commons brings ruin to all.”[8]

Since its publication in 1968, Hardin’s account has been widely adopted by academics and policy makers, and used to justify stealing indigenous peoples’ lands, privatizing health care and other social services, giving corporations ‘tradable permits’ to pollute the air and water, and more. Remarkably, few of those who have accepted Hardin’s views as authoritative notice that he provided no evidence to support his sweeping conclusions. He claimed that “tragedy” was inevitable, but he didn’t show that it had happened even once.[9]

Scholars who have actually studied commons-based agriculture have drawn very different conclusions. “What existed in fact was not a ‘tragedy of the commons’ but rather a triumph: that for hundreds of years — and perhaps thousands, although written records do not exist to prove the longer era — land was managed successfully by communities.”[10]

The most important account of how common-field agriculture in England actually worked is Jeanette Neeson’s award-winning book, Commoners: Common Right, Enclosure and Social Change in England, 1700-1820. Her study of surviving manorial records from the 1700s showed that the common-field villagers, who met two or three times a year to decide matters of common interest, were fully aware of the need to regulate the metabolism between livestock, crops and soil.

“The effective regulation of common pasture was as significant for productivity levels as the introduction of fodder crops and the turning of tilled land back to pasture, perhaps more significant. Careful control allowed livestock numbers to grow, and, with them, the production of manure. … Field orders make it very clear that common-field villagers tried both to maintain the value of common of pasture and also to feed the land.”[11]

Village meetings selected “juries” of experienced farmers to investigate problems, and introduce permanent or temporary by-laws. Particular attention was paid to “stints” — limits on the number of animals allowed on the pasture, waste, and other common land. “Introducing a stint protected the common by ensuring that it remained large enough to accommodate the number of beasts the tenants were entitled to. It also protected lesser commoners from the commercial activities of graziers and butchers.”[12]

Juries also set rules for moving sheep around to ensure even distribution of manure, and organized the planting of turnips and other fodder plants in fallow fields, so that more animals could be fed and more manure produced. The jury in one of the manors that Neeson studied allowed tenants to pasture additional sheep if they sowed clover on their arable land — long before scientists discovered nitrogen and nitrogen-fixing, these farmers knew that clover enriched the soil.[13]

And, given present-day concerns about the spread of disease in large animal feeding facilities, it is instructive to learn that eighteenth century commoners adopted regulations to isolate sick animals, stop hogs from fouling horse ponds, and prevent outside horses and cows from mixing with the villagers’ herds. There were also strict controls on when bulls and rams could enter the commons for breeding, and juries “carefully regulated or forbade entry to the commons of inferior animals capable of inseminating sheep, cows or horses.”[14]

Neeson concludes, “the common-field system was an effective, flexible and proven way to organize village agriculture. The common pastures were well governed, the value of a common right was well maintained.”[15]

Commons-based agriculture survived for centuries precisely because it was organized and managed democratically by people who were intimately involved with the land, the crops and the community. Although it was not an egalitarian society, in some ways it prefigured what Karl Marx, referring to a socialist future, described as “the associated producers, govern[ing] the human metabolism with nature in a rational way.”[16]

Class Struggles

That’s not to say that agrarian society was tension free. There were almost constant struggles over how the wealth that peasants produced was distributed in the social hierarchy. The nobility and other landlords sought higher rents, lower taxes and limits on the king’s powers, while peasants resisted landlord encroachments on their rights, and fought for lower rents. Most such conflicts were resolved by negotiation or appeals to courts, but some led to pitched battles, as they did in 1215 when the barons forced King John to sign Magna Carta, and in 1381 when thousands of peasants marched on London to demand an end to serfdom and the execution of unpopular officials.

Historians have long debated the causes of feudalism’s decline: I won’t attempt to resolve or even summarize those complex discussions here.[17] Suffice it to say that by the early 1400s in England, the feudal aristocracy was much weakened. Peasant resistance had effectively ended hereditary serfdom and forced landlords to replace labor-service with fixed rents, while leaving common field agriculture and many common rights in place. Marx described the 1400s and early 1500s, when peasants in England were winning greater freedom and lower rents, as “a golden age for labor in the process of becoming emancipated.”[18]

But that was also a period when longstanding economic divisions within the peasantry were increasing. W.G. Hoskins described the process in his classic history of life in a Midland village.

“During the fifteenth and sixteenth centuries there emerged at Wigston what may be called a peasant aristocracy, or, if this is too strong a phrase as yet, a class of capitalist peasants who owned substantially larger farms and capital resources than the general run of village farmers. This process was going on all over the Midlands during these years …”[19]

Capitalist peasants were a small minority. Agricultural historian Mark Overton estimates that “in the early sixteenth century, around 80 per cent of farmers were only growing enough food for the needs of their family household.” Of the remaining 20%, only a few were actual capitalists who employed laborers and accumulated ever more land and wealth. Nevertheless, by the 1500s two very different approaches to the land co-existed in many commons communities.

“The attitudes and behavior of farmers producing exclusively for their own needs were very different from those farmers trying to make a profit. They valued their produce in terms of what use it was to them rather than for its value for exchange in the market. … Larger, profit orientated, farmers were still constrained by soils and climate, and by local customs and traditions, but also had an eye to the market as to which crop and livestock combinations would make them most money.”[20]

As we’ll see, that division eventually led to the overthrow of the commons.

Primitive Accumulation

For Marx, the key to understanding the long transition from agrarian feudalism to industrial capitalism was “the process which divorces the worker from the ownership of the conditions of his own labor,” which itself involved “two transformations … the social means of subsistence and production are turned into capital, and the immediate producers are turned into wage-laborers.”[21]

“Nature does not produce on the one hand owners of money or commodities, and on the other hand men possessing nothing but their own labor-power. This relation has no basis in natural history, nor does it have a social basis common to all periods of human history. It is clearly the result of a past historical development, the product of many economic revolutions, of the extinction of a whole series of older formations of social production.”[22]

A decade before Capital was published, Marx summarized that historical development in an early draft.

“It is … precisely in the development of landed property that the gradual victory and formation of capital can be studied. … The history of landed property, which would demonstrate the gradual transformation of the feudal landlord into the landowner, of the hereditary, semi-tributary and often unfree tenant for life into the modern farmer, and of the resident serfs, bondsmen and villeins who belonged to the property into agricultural day laborers, would indeed be the history of the formation of modern capital.”[23]

In Section VIII of Capital Volume 1, titled “The So-Called Primitive Accumulation of Capital,” he expanded that paragraph into a powerful and moving account of the historical process by which the dispossession of peasants created the working class, while the land they had worked for millennia became the capitalist wealth that exploited them. It is the most explicitly historical part of Capital, and by far the most readable. No one before Marx had researched the subject so thoroughly — Harry Magdoff once commented that on re-reading it, he was immediately impressed by the depth of Marx’s scholarship, by “the amount of sheer digging, hard work, and enormous energy in the accumulated facts that show up in his sentences.”[24]

Since Marx wrote Capital, historians have published a vast amount of research on the history of English agriculture and land tenure — so much that a few decades ago, it was fashionable for academic historians to claim that Marx got it all wrong, that the privatization of common land was a beneficial process for all concerned. That view has little support today. Of course it would be very surprising if subsequent research didn’t contradict Marx in some ways, but while his account requires some modification, especially in regard to regional differences and the tempo of change, Marx’s history and analysis of the commons remains essential reading.[25]

*****

The next installments in this series will discuss how, in two great waves of social change, landlords and capitalist farmers “conquered the field for capitalist agriculture, incorporated the soil into capital, and created for the urban industries the necessary supplies of free and rightless proletarians.”[26]

To be continued ….

[1] Wendell Berry, Wendell Berry: Essays 1969-1990, ed. Jack Shoemaker (Library of America, 2019), 317.

[2] https://www.unccd.int/news-events/better-land-use-and-management-critical-achieving-agenda-2030-says-new-report

[3] Karl Marx, Capital: A Critique of Political Economy, trans. David Fernbach, vol. 3, (Penguin Books, 1981), 216

[4] John Bellamy Foster, Brett Clark, and Hannah Holleman, “Marx and the Commons,” Social Research (Spring 2021), 2-3.

[5] See “Reasons for Inequality Among Medieval Peasants,” in Rodney Hilton, Class Conflict and the Crisis of Feudalism: Essays in Medieval Social History (Hambledon Press, 1985), 139-151.

[6] Rodney Hilton, Bond Men Made Free: Medieval Peasant Movements and the English Rising of 1381 (Routledge, 2003 [1973]), 32.

[7] Rodney Hilton, Bond Men Made Free, 34.

[8] Garrett Hardin, The Tragedy of the Commons, Science, December 13, 1968.

[9] Ian Angus, The Myth of the Tragedy of the Commons, Climate & Capitalism, August 25, 2008; Ian Angus, Once Again: ‘The Myth of the Tragedy of the Commons’, Climate & Capitalism, November 3, 2008.

[10] Susan Jane Buck Cox, No Tragedy of the Commons, Environmental Ethics 7, no. 1 (1985), 60.

[11] J. M. Neeson, Commoners: Common Right, Enclosure and Social Change in England, 1700-1820 (Cambridge University Press, 1993), 113.

[12] J. M. Neeson, Commoners, 117.

[13] J. M. Neeson, Commoners, 118-20.

[14] J. M. Neeson, Commoners, 132.

[15] J. M. Neeson, Commoners, 157.

[16] Karl Marx, Capital Volume 3, trans. David Fernbach, (Penguin Books, 1981), 959.

[17] For an insightful summary and critique of the major positions in those debates, see Henry Heller, The Birth of Capitalism: A Twenty-First Century Perspective (Pluto Press, 2011).

[18] Karl Marx, Grundrisse, trans. Martin Nicolaus (Penguin Books, 1973), 510.

[19] W. G. Hoskins, The Midland Peasant: The Economic and Social History of a Leicestershire Village (Macmillan., 1965), 141.

[20] Mark Overton, Agricultural Revolution in England: The Transformation of the Agrarian Economy, 1500-1850 (Cambridge University Press, 1996), 8, 21.

[21] Karl Marx, Capital Volume, 1, 874.

[22] Karl Marx, Capital Volume 1, 273.

[23] Karl Marx, Grundrisse, 252-3.

[24] Harry Magdoff, “Primitive Accumulation and Imperialism,” Monthly Review (October 2013), 14.

[25] “The So-Called Primitive Accumulation” — Chapters 26 through 33 of Capital Volume 1 — can be read on the Marxist Internet Archive, beginning here. The somewhat better translation by Ben Fowkes occupies pages 873 to 940 of the Penguin edition.

[26] Karl Marx, Capital Volume 1, 895.

by DGR News Service | Sep 15, 2021 | Biodiversity & Habitat Destruction, Climate Change, Colonialism & Conquest, Indigenous Autonomy, Mining & Drilling, Movement Building & Support, Repression at Home, Toxification

This article originally appeared in Truthout.

Featured image: On September 7, 2021, Water Protectors erected multiple blockades at a major U.S.-Canadian tar sands terminal in Clearbrook, Minnesota, in direct opposition to Enbridge’s Line 3. Courtesy of the Giniw Collective.

By Kelly Hayes, Truthout

Amid record hurricanes, wildfires and droughts, battles are being waged over the fate of the Earth. Many of those battles are being fought by Indigenous people, and by others whose relationship to life, land and one another compels them to push back against an extractive, death-making economy that renders people and ecosystems disposable. On the front lines of the struggle to halt construction of Enbridge’s new Line 3 pipeline — which would bring nearly a million barrels of tar sands per day from Alberta, Canada, to Superior, Wisconsin — Water Protectors have locked themselves to excavators and drills, and overturned cars and barrels of cement, while also deploying aerial blockades, including elaborate tripods and tree-sits. In scattered encampments that run along a 300-mile stretch of pipeline construction, a culture defined by mutual aid, and a spiritual and physical struggle to defend the Earth, has held strong in the face of brutality and an increasingly entrenched alliance between police and the corporate forces fueling climate catastrophe.

I recently spoke with Giniw Collective founder Tara Houska, a citizen of Couchiching First Nation, over a shaky internet connection, as she held space at the collective’s Namewag Camp in Minnesota. The camp, which is led by Indigenous women and two-spirit people, was founded by the Giniw Collective in 2018, as Minnesota’s final permit decision on Line 3 drew near. Houska says she invited Native matriarchs, including LaDonna Brave Bull Allard and Winona LaDuke, among others, to initiate the effort. “We laid out our prayers and our songs to begin this phase,” Houska told me.

Since then, the Namewag Camp, says Houska, has been “a home for many people.” Some people have spent years at the encampment, while others have held space for months, weeks or even a few days. “It really depends on the person or persons that are coming through,” says Houska. The culture of the camp emphasizes direct action, mutual aid and Native traditions. “We’ve trained well over 1000 folks in non-violent direct action, decolonization, traditional knowledge and life in balance,” says Houska. People who call the camp home are committed to stopping the pipeline, but Houska says making a home at Namewag also requires a commitment to mutual aid as a way of life. “I think we’re trying to create a balance, a place that is more reflective of balance, and deep values that are very much needed in the climate movement, and also just generally in the world,” Houska told me, adding that, “the first structure that was built in this camp was actually our sweat lodge.” The encampment also includes a “very large, beautiful garden.”

Houska was not always an activist on the front lines. “I started out as a D.C. lawyer back in 2013, after law school, and worked on a lot of different issues for tribal nations, and saw the treatment of our people on the hill, and through the law,” says Houska. She engaged with legal efforts to thwart the construction of the Keystone XL pipeline, and efforts to stop the project that would eventually be known as Line 3, but Houska ultimately felt called to fight for the Earth “in a different way.” Houska travelled to Standing Rock in 2016 and “spent six months out there learning and resisting.”

While some Water Protectors involved in the Line 3 protests carry lessons from Standing Rock, the two struggles have manifested differently. The movement in Standing Rock drew an unprecedented assemblage of Natives from over 300 federally recognized tribes, and other Indigenous and non-Indigenous co-strugglers. Thousands of people converged on a cluster of camps, the largest of which was known as Oceti Sakowin. Houska says a variety of nations and groups are also represented in the Line 3 struggle, but rather than being relatively centralized, Line 3 encampments are staggered across 334 miles of pipeline construction. “We also have been fighting this pipeline during a pandemic,” Houska noted, “which means a lot of caution and precaution around COVID-19 and making sure everyone is healthy and safe, and that we’re not putting anyone at risk.”

Line 3 opponents say the pipeline, once fully operational, would be the carbon pollution equivalent of 50 coal-fired power plants. As an editorial that will be published in 200 health journals worldwide this fall, ahead of the UN General Assembly and the COP26 climate summit in Glasgow, states, “The greatest threat to global public health is the continued failure of world leaders to keep the global temperature rise below 1.5°C and to restore nature.”

The pipeline would also tunnel under 20 rivers, including the Mississippi, threatening the drinking water supply of millions of people. In 2010, 1.2 million gallons of oil spilled from Enbridge’s Line 6B pipeline into the Kalamazoo River, in one of 800 oil spills the company experienced between 1999 and 2010.

While regulatory battles and legal maneuvers are crucial in any fight to stop a pipeline, Houska says that land defense, and the “building of a resistance community on the front lines” is an “under-respected, undervalued, but critical component to a healthy movement.” Houska says the work of building that communal effort, and sustaining it, has been “beautiful, hard, sad, [and] sometimes painful.” Houska explained: “Police have been getting pretty brutal in recent weeks. They’ve been shooting ‘less lethals’ at us, and using pain compliance tactics. So torturing people, really engaging in behaviors that are quite shocking, I think. Which means a lot of care, and community is really important for us on the front lines.”

Houska says sustaining the struggle also means making time to acknowledge “the hurt that we’re experiencing in real time” while also naming and uplifting “the reasons we’re engaging in struggle, [which is for] the littles, and those to come, and the four-legged and the winged, and the rivers, and the wild rice.”

Houska also notes that the violence of fossil fuel extraction embodies the longstanding violence of colonialism, with large influxes of transient workers at so-called “man camps” (temporary housing camps of mostly male pipeline construction workers) destroying the life-giving ecosystems that sustain Native communities, while also inflicting violence on Indigenous women, girls and two-spirit people. For years, Native leaders have sought to raise awareness about the measurable increase in sexual assaults, murders and disappearances of Native women in areas where “man camps” are established. To highlight this threat, Water Protectors hosted by the Giniw Collective’s camp recently staged a blockade action in front of the Line 3 “man camp,” in which an “all-BIPOC group of mostly Indigenous femmes [and] two-spirits” locked themselves to an overturned vehicle, and other equipment.

“Man camps” are the modern embodiment of colonial raiding parties that have historically seized upon Native land, looted Indigenous resources and inflicted sexual violence on Native women. Today, pipeline workers and police inflict the violence of colonialism on Indigenous people, enacting the true character of capitalism for the world to see, while relying on the public’s lack of concern for Native people and the environment as they commit atrocities in plain sight.

Houska says that land defense, and the “building of a resistance community on the front lines” is an “under-respected, undervalued, but critical component to a healthy movement.”

A war is being waged against land and water defenders in the U.S., just as a war is being waged globally against environmental activists, by corporations and world governments, in order to maintain the repetitions of capitalism: extraction, exploitation, destruction, disposal, and the consolidation of wealth and resources. Globally, violence against environmental activists has hit record highs in recent years, with Indigenous people facing disproportionately high rates of murder and brutality for their organizing. Indigenous people make up less than 5 percent of the world’s population, but steward over 80 percent of the world’s remaining biodiversity. In some parts of the world, such as Colombia and the Philippines, the assassination of Indigenous activists has become increasingly common. Here in the United States, Indigenous activists have faced escalating violence and criminalization while acting in opposition to pipeline construction and other extraction efforts.

While many people recoil from any discussion of the reality of climate change, catastrophes like Hurricane Ida, and the Dixie and Caldor fires in California, are making the subject harder to avoid. According to the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change 2021 climate report, environmental catastrophes will continue to accelerate over the coming decades, but human beings still have something to say about the severity of the damage. Coming to terms with the existential threat of climate collapse can easily lead to distress and despair, but with so much at stake, it is imperative that we not only absorb statistics and haunting images of destruction, but also zero in on the front lines of struggles like the fight against Line 3, where Water Protectors are modeling a relationship with the Earth that could help guide us into a new era.

The Theft of Water

The Giniw Collective has been vocal about Enbridge’s overuse of local water supplies during an ongoing drought. Enbridge was initially authorized to pump about 510 million gallons of water out of the trenches it’s digging, but in June, the company claimed it had encountered more groundwater than it had anticipated, and obtained permission to pump up nearly 5 billion gallons of water, in order to complete the project. According to Line 3 opponents, Enbridge paid a fee of $150 to adjust its permit.

Giniw Collective members say it’s unconscionable that the Minnesota Department of Natural Resources would allow Enbridge to displace so much water, particularly during a drought. “We’ve been in an extreme drought all summer long,” says Houska. “The rivers have been dry, the waterfalls are empty, and the wildfires have spread into Ontario and up on the north shore of Lake Superior.”

Activists organizing against Line 3 and members of the White Earth Nation argue that Enbridge’s voracious consumption of local groundwater threatens local wetlands, including cherished wild rice beds. “With higher than average temperatures and lower than average precipitation, displacing this amount of water will have a direct detrimental impact on the 2021 wild rice crop,” wrote Michael Fairbanks and Alan Roy, tribal chairman and secretary-treasurer of the White Earth Nation.

For refusing to embrace the death march of capitalism, and resisting the destruction of most life on Earth, two Line 3 opponents are being charged with attempted assisted suicide.

According to the UN, “By 2025, 1.8 billion people will be living in countries or regions with absolute water scarcity, and two-thirds of the world’s population could be living under water stressed conditions.” Scientific projections suggest that many regions of the U.S. may see their water supplies reduced by a third, even as they face increased demand for water due to a growing population. As world temperatures rise, and water scarcity continues to escalate, Enbridge is displacing 500 billion gallons of groundwater to build a pipeline that will transport 915,000 barrels of tar sands crude oil per day, threatening more than 200 water ecosystems — including 389 acres of wild rice, which are a source of sacred sustenance for the Anishinaabe.

The White Earth Nation has brought a “rights of nature” lawsuit against the Minnesota Department of Natural Resources, in an effort to defend wild rice, or manoomin, which means “good berry” in the Ojibwe language, against the destruction being waged by Enbridge. According to Mary Annette Pember, a citizen of the Red Cliff Ojibwe tribe, for the Ojibwe people, manoomin “is like a member of the family, a relative,” which means “legally designating manoomin as a person … aligns with the Ojibwe world view.” As Pember writes, “According to [the United Nations’ 6th Assessment on Climate Change], recognition of Indigenous rights, governance systems and laws are central to creating effective adaptation and sustainable development strategies that can save humanity from the impacts of climate change.”

The suit is only the second rights of nature case to be filed in the United States and the first to be filed in tribal court. But as Pember notes, “Several tribes, however, have incorporated rights of nature into their laws.”

According to the nonprofit organization Honor the Earth, “The proposed new oil pipelines in northern MN violate the treaty rights of the Anishinaabeg by endangering critical natural resources in the 1854, 1855, and 1867 treaty areas.” In a statement outlining the alleged treaty violations, Honor the Earth explains, “The pipelines threaten the culture, way of life, and physical survival of the Ojibwe people. Where there is wild rice, there are Anishinaabeg, and where there are Anishinaabeg, there is wild rice. It is our sacred food. Without it we will die. It’s that simple.”

Buying the Police

During the movement in Standing Rock, we saw that resistance to pipeline construction can generate significant costs for local governments. In 2018, Morton County Commissioner Cody Schulz claimed that protests that aimed to stop the Dakota Access Pipeline (DAPL) cost the county almost $40 million. But rather than serving as a deterrent to other municipalities considering pipeline permits, the cost of the NoDAPL protests have been leveraged by authorities to more blatantly merge the interests of police and oil companies.

The Minnesota Public Utilities Commission included a provision in Enbridge’s permit for the project that requires the company to establish an escrow trust that would reimburse local law enforcement for any mileage, wages, protective gear and training related to the construction of Line 3. In order to access the funds, law enforcement agencies submit requests for reimbursement to a state appointed account manager — a former deputy police chief — who approves or denies the requests. In April of 2020, The Minnesota Reformer reported that Enbridge had paid over $500,000 to local law enforcement in support of pipeline construction. That number has since ballooned to $2 million.

Protesters who have engaged in direct action to stop Line 3 say police have bragged to arrestees that they are enjoying themselves and getting paid overtime.

“The level of brutality that is experienced by Indigenous people and allies in struggle with us is extreme,” Houska told me. “About a month ago now, I was a part of a group that experienced rubber bullets and mace being fired at us at very, very close range,” said Houska. “I was hit several times, but I also witnessed young people with their heads split open, bleeding down their faces … and sheriffs have been using pain compliance on people, which is essentially torture. They dislocated someone’s jaw a couple weeks ago.”

“Living at Namewag shows us what a post-capitalist world could begin to look like.”

As Ella Fassler recently reported in Truthout, “More than 800 Water Protectors have been arrested or cited in the state since November 2020, when the Minnesota Department of Natural Resources and the Minnesota Pollution Control Agency (MPCA) approved the Line 3 permit.” The total number of arrests along Line 3, since November of 2020, has surpassed the total number of arrests during the Standing Rock protests, in which nearly 500 people were arrested. The charges Water Protectors and land defenders face are likewise escalating. According to the Pipeline Legal Action Network, 80 Water Protectors were charged with felonies during July and August of 2021, and as Mollie Wetherall, a legal support organizer with the legal action network told Fassler, “It’s clear that they really are in a moment where they want to intimidate people as the construction of this pipeline winds down.”

Direct actions similar to those that garnered misdemeanor charges two years ago have more recently led to felony charges. According to the Giniw Collective, which has bailed out hundreds of Water Protectors, individual bonds have often run between $10,000 and $25,000, making bail fundraising a crucial point of solidarity work.

Disturbingly, in late July, two Water Protectors were charged with felony assisted suicide for allegedly crawling into the pipeline as part of a lockdown action. Officials claim the pipeline was an estimated 130 degrees and lacked oxygen. The criminal complaint lodged against the two activists claims that they “did intentionally advise, encourage, or assist another who attempted but failed to take the other’s own life.” The charge of felony assisted suicide carries a 7-year prison sentence, $14,000 fine or both. If convicted, the Water Protectors could face up to 13 years behind bars.

For refusing to embrace the death march of capitalism, and resisting the destruction of most life on Earth, two Line 3 opponents are being charged with attempted assisted suicide. “These are 20, 21, 22-year-old people, who are literally chaining themselves to the machines, crawling inside of pipes, doing everything and anything they can to have a future,” says Houska. “And the charges being waged, like felony theft and felony assisted suicide for people who are trying to protect all life, [are] absolutely appalling, and a horrific reality of Water Protectors being imprisoned while the world burns around us.”

Members of Congress, including “the Squad,” signed a letter to President Biden on August 30, 2021, calling on the president to “uphold the rights guaranteed to Indigenous people under federal treaties and fulfill tribal requests for a government-to-government meeting concerning Line 3.” Among other concerns, the letter cited the troubling financial ties between Enbridge and local law enforcement, stating:

Law enforcement entities in the region have received around $2 million from Enbridge to pay for police activity against water protectors, which has included staggering levels of violence, tear gas, and rubber bullets. While Enbridge was required to pay these costs under project permits, leaders have noted they create a conflict of interest as law enforcement are incentivized to increase patrols and arrests surrounding pipeline construction.

Minnesota Congresswoman Ilhan Omar also hosted a press conference on September 3 to draw further attention to the struggle to stop Line 3, which included remarks from U.S. Representatives Cori Bush, Ayanna Pressley, Rashida Tlaib and Sen. Mary Kunesh-Podein. During the press conference, Omar declared, “The climate crisis is happening and the last thing we need to do is allow the very criminals who created this crisis to build more fossil fuel infrastructure.” Bush, Presseley, Tlaib and Kunesh-Podein also visited the Giniw Collective’s Namewag Camp to hear from Water Protectors firsthand about the struggle. Rep. Alexandria Ocasio-Cortez tweeted that she had planned to join the group as well, but her plans were derailed by the climate impacts of Hurricane Ida in her district.

Finding a Home on the Front Lines

Despite the brutality protectors have faced, people have continued to answer the call to head to the front lines. After years of engaging in solidarity actions at banks and financial institutions that are funding the construction of Line 3, one activist — who asked to be identified by the name Marla, so as not to facilitate state surveillance of her actions — left her job as a nanny in Chicago and headed to the front lines in May of 2021. “I had never seen a pipeline before,” Marla told me. “I had only done solidarity organizing up until this point. Land defense was something new entirely to me, but I knew that bank actions alone were not going to stop this pipeline.” Marla saw heading to the front lines as “a tangible way to show up as an accomplice for Indigenous sovereignty.”

While living at Namewag has meant bearing witness to police violence, deforestation and constant state surveillance, Marla says it has also meant experiencing “a microcosm of the world we all want to build.” Marla says the Giniw Collective’s camp “an incredible place to live in community and resistance.”

“Living at Namewag shows us what a post-capitalist world could begin to look like,” says Marla, “where labor is valued because it keeps our community safe, skilled up and fed from the land.” Marla says the camp is a place “to see accountability in action, to learn and unlearn, and do better.” While police and the surveillance state can be intimidating, Marla says, “We keep each other safe working overnight security shifts by night and supporting folks taking action by day.” Marla also describes the camp as a joyful place, even amid pain and struggle. “Cooking meals from the garden, living outside among the trees, washing the camp’s dishes, [providing] elder and childcare, and making space for joy — all of these things sustain us.”

“People have consistently been showing up for the struggle,” Houska told me. “And that is a beautiful thing to witness and be part of.” Houska says that almost 90 percent of Line 3 construction is now complete. “We are still resisting, in the face of that reality,” says Houska. “So, if you’re planning to show up, please show up with your heart, and your good intentions and do your best to find your way to the place that calls to you.” Houska also encourages supporters to “use whatever platform or voice and agency you have to call on the Biden administration, and also to call on other people around you” to take action to stop the pipeline.

“This fight is not just about looking upwards,” says Houska. “It’s also looking at each other. This is our world, and no one else is going to protect it, but all of us.”

Copyright © Truthout.org. Reprinted with permission.

To learn more about other powerful movement work like the struggle against Line 3 and mutual aid efforts across the country, check out our podcast “Movement Memos,” which will release its next episode on Wednesday, September 15.

Kelly Hayes

Kelly Hayes is the host of Truthout’s podcast “Movement Memos” and a contributing writer at Truthout. Kelly’s written work can also be found in Teen Vogue, Bustle, Yes! Magazine, Pacific Standard, NBC Think, her blog Transformative Spaces, The Appeal, the anthology The Solidarity Struggle: How People of Color Succeed and Fail At Showing Up For Each Other In the Fight For Freedom and Truthout’s anthology on movements against state violence, Who Do You Serve, Who Do You Protect? Kelly is also a direct action trainer and a co-founder of the direct action collective Lifted Voices. Kelly was honored for her organizing and education work in 2014 with the Women to Celebrate award, and in 2018 with the Chicago Freedom School’s Champions of Justice Award. Kelly’s movement photography is featured in “Freedom and Resistance” exhibit of the DuSable Museum of African American History. To keep up with Kelly’s organizing work, you can follow her on Facebook and Twitter.

by DGR News Service | Sep 11, 2021 | Colonialism & Conquest, Male Violence, Repression at Home, Women & Radical Feminism

Editor’s note: They hate our freedom, spreading democracy and your with us or you are against us has failed. And all we needed was another five more years of fight them over there, so we don’t have to fight them here. A War on Terrorism can never be won if you are a terrorist.

This article originally appeared in FAIRNESS & ACCURACY IN REPORTING.

By JULIE HOLLAR

Just as US corporate news media “discovered” Afghan women’s rights only when the US was angling for invasion, their since-forgotten interest returned with a vengeance as US troops exited the country.

After September 11, 2001, the public was subjected to widespread US news coverage of burqa-clad Afghan women in need of US liberation, and celebratory reports after the invasion. Time magazine (11/26/01), for instance, declared that “the greatest pageant of mass liberation since the fight for suffrage” was occurring, as “female faces, shy and bright, emerged from the dark cellars” to stomp on their old veils. In a piece by Nancy Gibbs headlined “Blood and Joy,” the magazine told readers this was “a holiday gift, a reminder of reasons the war was worth fighting beyond those of basic self-defense” (FAIR.org, 4/9/21).

The media interest was highly opportunistic. Between January 2000 and September 11, 2001, there were 15 US newspaper articles and 33 broadcast TV reports about women’s rights in Afghanistan. In the 16 weeks between September 12 and January 1, 2002, those numbers skyrocketed to 93 and 628, before plummeting once again (Media, Culture & Society, 9/1/05).

Suddenly remembering women

Now, as the US finally is withdrawing its last troops, many corporate media commentators put women and girls at the center of the analysis, as when Wolf Blitzer (CNN Situation Room, 8/16/21), after referring to “the horror awaiting women and girls in Afghanistan,” reported:

President Biden saying he stands, and I’m quoting him now, squarely, squarely behind this decision to withdraw US forces from Afghanistan, despite the shocking scene of chaos and desperation as the country fell in a matter of only a few hours under Taliban control, and the group’s extremist ideology has tremendous and extremely disturbing implications for everyone in Afghanistan, but especially the women and girls.

This type of framing teed up hawkish guests, who proliferate on TV guest lists, to use women as a political football to oppose withdrawal. Blitzer guest Rep. Adam Kinzinger (R.-Illinois), for instance, argued:

Look at the freedom that is being deprived from the Afghan people as the Taliban move into Afghan, or moving into parts of Afghanistan now, and you know how much freedom they had. Look at the number of women that are out there making careers, that are thought leaders, that are academics, that never would have happened under the Taliban leadership…. The devastation you are seeing today is why that small footprint of 2,500 US troops was so important.

Sen. Joni Ernst (R.-Iowa) gladly gave Jake Tapper (CNN Newsroom, 8/16/21) her take on the situation after CNN aired a report on the situation for women:

As you mentioned, for women and younger girls, this is also very devastating for them. The humiliation that they will endure at the hands of the Taliban all around this is just a horrible, horrible mar on the United States under President Joe Biden.

‘America rescued them’

Charity Wallace claimed in the Wall Street Journal (8/17/21) that Afghan “women and girls…made enormous progress over the past 20 years.”

Such analysis depends on the assumption that the US invasion and occupation “saved” Afghan women. In the Wall Street Journal (8/17/21), an op-ed by former George W. Bush staffer Charity Wallace ran under the headline : “The Nightmare Resumes for Afghan Women: America Rescued Them 20 Years Ago. How Can We Abandon Them to the Taliban Again?”

Two days later, a news article in the Journal (8/19/21) about the fate of women in Afghanistan explained: “Following the 2001 invasion, US and allied forces invested heavily to promote gender equality.”

The Associated Press (8/14/21), in a piece headlined, “Longest War: Were America’s Decades in Afghanistan Worth It?,” noted at the end that “some Afghans—asked that question before the Taliban’s stunning sweep last week—respond that it’s more than time for Americans to let Afghans handle their own affairs.” It continued, “But one 21-year-old woman, Shogufa, says American troops’ two decades on the ground meant all the difference for her.” After describing Shogufa’s experience for five paragraphs, the piece concludes with her “message to Americans”:

“Thank you for everything you have done in Afghanistan,” she said, in good but imperfect English. “The other thing was to request that they stay with us.”

Atlantic’s Caitlin Flanagan (8/19/21): “The United States military made it possible for those women to experience a measure of freedom. Without us, that’s over.”

Perhaps the most indignant media piece about Afghan women came from Caitlin Flanagan in the Atlantic (8/19/21), “The Week the Left Stopped Caring About Human Rights.” Flanagan argued:

Leave American troops idle long enough, and before you know it, they’re building schools and protecting women. We found an actual patriarchy in Afghanistan, and with nothing else to do, we started smashing it down. Contra the Nation, it’s hard to believe that Afghan women “won” gains in human rights, considering how quickly those gains are sure now to be revoked. The United States military made it possible for those women to experience a measure of freedom. Without us, that’s over.

Flanagan pointed to Pakistani activist Malala Yousafzai, whom she accused “critics of the war” of forgetting, saying Yousafzai “appealed to the president to take ‘a bold step’ to stave off disaster.”

Next to last in women’s rights

Such coverage gives the impression that Afghan women desperately want the US occupation to continue, and that military occupation has always been the only way for the US to help them. But for two decades, women’s rights groups have been arguing that the US needed to support local women’s efforts and a local peace process. Instead, both Democrat and Republican administrations continued to funnel trillions of dollars into the war effort, propping up misogynist warlords and fueling violence and corruption.

It’s hard to read an essay (New York Times, 8/17/21) that addresses “the countries that have used Afghans as pawns in their wars of ideology and greed” and says that the Afghan people “have been trapped for generations in proxy wars of global and regional powers” as a call for unending military occupation.

Contra Flanagan’s insinuation, Yousafzai didn’t ask Biden to continue the occupation. In an op-ed for the New York Times (8/17/21) that most clearly laid out her appeal, she asked for humanitarian aid in Afghanistan and for refugees fleeing the country. In fact, her take on the US occupation’s role in women’s rights (BBC, 8/17/21) is much more critical than most voices in the US corporate media: “There had been very little interest in focusing on the humanitarian aid and the humanitarian work.”

As human rights expert Phyllis Bennis told FAIR’s radio program CounterSpin (2/17/21), Malalai Joya, a young member of parliament, told her in the midst of the 2009 troop surge that women in Afghanistan have three enemies: the Taliban, warlords supported by the US and the US occupation. “She said, ‘If you in the West could get the US occupation out, we’d only have two.’”

Things did get better for some women, mostly in the big cities, where new opportunities in education, work and political representation became possible with the Taliban removed from power. But as Shreya Chattopadhyay pointed out in the Nation (8/9/21), the US commitment to women was little more than window dressing on its war, devoting roughly 1,000 times more funding to military expenses than to women’s rights.

Passive consumers of US corporate news media might be surprised to learn that Afghanistan, in its 19th year under US occupation, ranked second-to-last in the world on women’s well-being and empowerment, according to the Women, Peace and Security Index (2019).

As the Index notes, Afghan women still suffer from discriminatory laws at a level roughly on par with Iraq, and an extraordinarily low 12.2% of women reported feeling safe walking alone at night in their community, more than 4 points lower than in any other country. And just one in three girls goes to school.

Wrong kind of ‘help’

In 2015, a 27-year-old Afghan woman named Farkhunda Malikzada was killed by an angry mob of men in Kabul after being falsely accused of burning a Quran; US-backed Afghan security forces watched silently (Guardian, 3/28/15). The shocking story spread around the world, but the only US TV network to mention it on air was PBS (7/2/15), which offered a brief report more than three months after the murder, when an Afghan appeals court overturned the death sentences given to some of the men involved.

FAIR turned up no evidence of Caitlin Flanagan ever writing about Malikzada, either—or about the plight of any Afghan woman before last week.

According to a Nexis search, TV news shows aired more segments that mentioned women’s rights in the same sentence as Afghanistan in the last seven days (42) than in the previous seven years (37).

The US did not “rescue” Afghan women with its military invasion in 2001, or its subsequent 20-year occupation. Afghan women need international help, but facile and opportunistic US media coverage pushes toward the same wrong kind of help that it’s been pushing for the last two decades: military “assistance,” rather than diplomacy and aid.

For more than 20 years, US corporate media could have listened seriously to Afghan women and their concerns, bringing attention to their own efforts to improve their situation. Instead, those media outlets are proving once again that Afghan women’s rights are only of interest to them when they can be used to prop up imperialism and the military industrial complex.

Research assistance: Elias Khoury

Correction: An earlier version of this post misstated Malala Yousafzai’s nationality. She is Pakistani.

by DGR News Service | Sep 10, 2021 | Biodiversity & Habitat Destruction, Colonialism & Conquest, Mining & Drilling, Movement Building & Support, Repression at Home

This article originally appeared in Counterpunch. Featured image: Sámi Parliament of Norway. Photograph Source: Utilisateur:Bel Adone – Public Domain

By GABRIEL KUHN

On June 23, a coalition of Sámi and environmentalist activists erected a protest camp in Nussir, the projected site of a gigantic copper mine in Sápmi, the traditional homeland of the Sámi people, northern Europe’s indigenous inhabitants. Today, Sápmi is divided by the borders of four nation states: Norway, Sweden, Finland, and Russia. None of these countries have censuses for the Sámi population, and reliable numbers are hard to come by. The use of the Sámi language, the electoral roll of the Sámi parliaments (there is one in each country), and self-identification are important criteria. Roughly, we can speak of about 70,000 Sámi in Norway, 20,000 in Sweden, 10,000 in Finland, and about 2,000 in Russia. For historical reasons, the Russian community is the most isolated.

Nussir lies on the “Norwegian side” of Sápmi, as it is called, near the town of Hammerfest. Mining has been a controversial issue in Sápmi for years. In Sweden, a strong protest movement emerged in 2013, objecting to the plans of opening an iron ore mine in Gállok. While the project is not off the table yet, the protests have caused the Swedish government to put a halt on it and promise a new investigation. This was a partial victory. The same can be said about the Nussir protests. Due to the protest camp and activists chaining themselves to machinery, work on the site has so far been impossible. More importantly, the company that was supposed to purchase the mine’s output, Aurubis, the world’s second-largest copper producer, terminated the “memorandum of understanding” with Nussir ASA in August 2020 due to concerns about “social corporate responsibility”. Whether Nussir ASA can find new investors after this prominent withdrawal remains to be seen.

Mining is not the only issue that threatens the Sámi’s control over their traditional lands and their livelihoods, most importantly reindeer herding and fishing. Wind farms are placed in what many still perceive as “uninhabited territory”, with the turbines making reindeer herding impossible for a radius of many miles. Hydropower plants are already scattered around Sápmi. The allegedly “uninhabited territory” is also used for military exercises, automotive testing, and, increasingly,  geoengineering trials. In Finland, a proposed “Arctic Railway” would cut through traditional reindeer pastures. Along the Deatnu River, which marks the border between Norway and Finland over a stretch of more than 250 kilometers, fishing legislation favors the interests of non-Sámi cabin owners over those of traditional Sámi salmon fishers. In Sweden, clear cuts by the state-owned lumber company Sveaskog threaten the existence of the Forest Sámi and their reindeer herds. All over Sápmi, the crucial question of land ownership remains unresolved, with the governments of Sweden and Finland still refusing to sign the International Labour Organization’ Indigenous and Tribal Peoples Convention (commonly known as ILO 169), while the Norwegian government does not deliver on the promises of the 2005 Finnmark Act that, formally, transferred land ownership in the province of Finnmark to the majority Sámi population.

geoengineering trials. In Finland, a proposed “Arctic Railway” would cut through traditional reindeer pastures. Along the Deatnu River, which marks the border between Norway and Finland over a stretch of more than 250 kilometers, fishing legislation favors the interests of non-Sámi cabin owners over those of traditional Sámi salmon fishers. In Sweden, clear cuts by the state-owned lumber company Sveaskog threaten the existence of the Forest Sámi and their reindeer herds. All over Sápmi, the crucial question of land ownership remains unresolved, with the governments of Sweden and Finland still refusing to sign the International Labour Organization’ Indigenous and Tribal Peoples Convention (commonly known as ILO 169), while the Norwegian government does not deliver on the promises of the 2005 Finnmark Act that, formally, transferred land ownership in the province of Finnmark to the majority Sámi population.

It is interesting to note that many of the named development projects are justified by citing “green energy” and “sustainability”. The planned mine in Nussir has been hailed as “the world’s first fully electrified mine with zero CO2 emissions”. Hydropower and wind power are praised as sustainable alternatives to fossil fuels. Railways as environmentally friendly means of transport. Even geoengineering shall, according to its proponents, help secure the future of our planet. The irony that, in Sápmi, a culture that has proven sustainable for thousands of years is threatened in the process seems to pass by these advocates of corporate environmentalism.

In Sápmi, people increasingly speak of a “green colonialism”. In a speech protesting mining projects, Marie Persson Njajta declared in April 2019: “We have to stop flirting with polluting industries and look at their consequences and their costs. We don’t want green colonialism. Sámi land shall not be exploited yet again, neither for wind power nor for metals to produce electric cars.”

It is ludicrous that, in 2021, there exists such an enormous gap between material justice for indigenous peoples and their symbolic integration into nation-states, which often implies cultural exploitation. At the same time, it is inspiring to see a generation of Sámi activists unwilling to accept this cynicism. Without recognizing the needs, knowledge, and guidance of indigenous peoples, social and climate justice movements will meet serious limitations.

by DGR News Service | Sep 8, 2021 | Biodiversity & Habitat Destruction, Listening to the Land, Movement Building & Support, Repression at Home

- A subsidiary of the San Miguel Corporation, one of the largest companies in the Philippines, has proposed a $500 million hydroelectric project that will overlap with a national park on Panay Island.

- Northwest Panay Peninsula Natural Park holds some of the central Philippines’ last stands of intact lowland rainforest, is home to endangered species including hornbills and the Visayan warty pig, and is a vital watershed for Panay and neighboring islands.

- The project is still not approved, and a growing coalition of activists and local governments opposes the plan.

Update: On Aug. 10, the village governments of Naboay and Malay publicly released resolutions opposing the hydroelectric project, citing concerns about the project’s potential impacts on the Northwest Panay Peninsula Natural Park, municipal and agricultural water supplies, and the area’s indigenous Ati communities.

This article originally appeared in Mongabay. Featured image: Visayan warty pigs (Sus cebifrons) at a wallow in the Philippines. Image by Shukran888 via Wikimedia Commons (CC BY-SA 4.0).

My Jun N. Aguirre

AKLAN, Philippines — Activists and local government officials in the central Philippines have lashed out at a recently announced plan to build a hydroelectric plant overlapping with a national park that’s home to rare and threatened species.

Strategic Power Development Corporation (SPDC), a subsidiary of Philippine mega conglomerate San Miguel Corporation, announced on July 13 its intention to build the $500 million, 300-megawatt pump-storage hydro facility in Malay municipality on the island of Panay. The project would include the construction of two dams and reservoirs, 9.6 kilometers (6 miles) of new roads, and the upgrade of 1.8 km (1.1 mi) of existing roads.

According to SPDC, the planned project near the confluence of the Nabaoy and Imbaroto rivers would consist of a 70-meter (230-foot) lower dam on the Naboay, with a 10.2-million-cubic-meter (2.7-billion-gallon) reservoir; and a 74 m (243 ft) upper dam with a 4.55-million-m3 (1.2-billion-gallon) reservoir extending to the Imbaroto. The company says the plant will provide energy to the regional grid to meet current and future peak demand, will support the local economy, and is part of President Rodrigo Duterte’s 2017-2040 Philippine Energy Plan.

Overall, the company says the complex would cover 122.7 hectares (303.2 acres), including 97.9 hectares (241.9 acres) of forest, of which 24.9 hectares (61.5 acres) are nominally protected land within Northwest Panay Peninsula Natural Park.

Significant biodiversity hotspot

Northwest Panay Peninsula Natural Park, which spans 12,009 hectares (29,676 acres) in the provinces of Aklan and Antique, was established in 2002 via a presidential proclamation. Home to critically endangered Visayan warty pigs (Sus cebifrons) and writhed-billed hornbills (Rhabdotorrhinus waldeni), as well as endangered Visayan hornbills (Penelopides panini), it has been locally recognized as a significant biodiversity hotspot since the 1990s.

The park holds some of the last remaining stands of primary lowland rainforest in the central Philippines, and serves as a key watershed providing potable water to Panay and neighboring islands.

Activists say the hydropower project puts water supplies for local communities at risk.

“The Nabaoy River is the lone source of potable water to nearby Boracay Island and to the residents of Malay,” said Ritchel Cahilig of the Aklan Trekkers Group. Boracay Island, separated from the park by a narrow strait, is a prime beach destination, recording 2 million tourist arrivals in 2019.

“I wonder how will they supply water to the residents especially during construction phase. During construction phase, for sure, large vehicles will be damaging the forest and the company seems do not have a clear alternative on how to restore what has been damaged,” Cahilig said.

The natural park is also home to a community of Indigenous Malay Ati people, who fish in the Nabaoy River and rely on the forests for sustenance.

Activists have also questioned the need for additional electrical capacity in the area. Citing reports from the National Grid Corporation of the Philippines, Melvin Purzuelo of the Green Forum-Western Visayas noted that from July 20-26, Panay Island’s average daily electricity consumption ranged from 345-364 MW, against existing capacity of 480 MW.

“It is clear now that a huge power supply is not needed at this time especially that the world is going through the COVID-19 pandemic,” Purzuelo said during a recent webinar.

Loss of local government support

SPDC’s proposal still requires approval from local governments and the Philippine Department of Environment and Natural Resources (DENR).

“The Malay [municipal government] have set a coordination meeting with the SPDC supposedly last August 2 to clarify issues involving the project but [the meeting] has been cancelled because of the COVID-19 pandemic,” Purzuelo said.

Local officials have distanced themselves from endorsing the proposal. In a phone interview, acting Malay Mayor Floribar Bautista said the SPDC had not approached him to discuss the details of the project since he assumed his post in July 2018.

“What I know is the project was endorsed by the previous administration. When I checked the documents, it’s lacking. It seems the project may have [been] railroaded. I could not endorse the project at this time since I do not know how the project would affect our town. All they have to do is to convince me if the hydro dam project is worth it,” he said.

The village of Nabaoy is also reportedly set to cancel its previous endorsement of the project, activists say. No official cancellation had been issued as of the time this article was published; but just as in the case of the Malay municipal government, the previous leadership of Nabaoy village had endorsed the project in the early months of 2018.

Without approval from the current local governments, the project can only push through with special permission from the DENR.

by DGR News Service | Sep 4, 2021 | Culture of Resistance, Mining & Drilling, Movement Building & Support, Repression at Home, Toxification

- The town of La Merced de Buenos Aires, in Ecuador, gained notoriety when it was invaded by illegal miners in 2017; for almost two years, the area was plagued by violence, prostitution and drug addiction.

- Authorities evicted the miners in 2019, but now the land may become home to legal mining operations, which many residents emphatically oppose.

- More than 300 people spent over a month blocking the path of the machinery, trucks and employees of Hanrine Ecuadorian Exploration and Mining S.A.

- The Ombudsman’s Office warns that confrontations will arise and has called on local, regional and national authorities to take immediate action.

This article originally appeared in Mongabay.

Featured image: This mountain in the parish of Buenos Aires was the epicenter of illegal mining between 2017 and 2019. Image by Iván Castaneira/Agencia Tegantai.

By Antonio José Paz Cardona | Translated by Sarah Engel

In 2017, the name “La Merced de Buenos Aires,” or simply “Buenos Aires,” became famous throughout Ecuador. This small parish located high in the Andean province of Imbabura was invaded by illegal miners who quickly took control of the mountains.

Giant mining camps made up of plastic tents garnered media attention, and the illegal nature of the mining brought violence, fear, and hopelessness to the area. The population that traditionally lived there cried out for help so that their territory would return to the tranquility that had characterized it in the past.

Several residents interviewed by Mongabay Latam say the gold rush attracted people from Peru, Venezuela, Colombia and southern Ecuador who intimidated the community. Former fighters from the now-dissolved FARC guerrilla group in Colombia even began to collect “vaccinations” — protection payments in exchange for not infringing upon them — and started to suppress the community in an attempt to dominate the illegal mining business.

In July 2019, 1,102 police officers, 1,200 soldiers and 20 prosecutors arrived in the area as part of an operation called “Radiant Dawn” (“Amanecer Radiante”). In the first few days of the raid, they managed to remove about 3,000 people from the mining camps. The operation also dismantled 30 gold-processing plants and a complex system of pulleys for transporting the gold. According to María Paula Romo, the minister of government at the time, the illegal gold trade in Buenos Aires was valued at about $500,000 per week.

For almost a year, an apparent sense of peace fell over the community. But in 2020, residents realized their land was being considered as a potential mining site again — this time in search of copper — by a company owned by an Australian firm. Since November 2017, the company has obtained eight mining titles in the area, one of which overlaps with the illegal mining area. The situation became increasingly tense in April, when more than 300 residents of Buenos Aires staged a protest on the outskirts of the parish in an attempt to stop the company’s trucks and machinery from starting mining activity in the territory.

Mining company sues dozens of people

The residents of Buenos Aires have declared their resistance. They say that since 2017, they have been invaded by illegal mining in this area, which has traditionally been dedicated to agriculture and cattle ranching. Now that legal miners want to exploit the land, many residents say they do not want any further involvement with mining.

The problem, according to a resident who asked not to be named for fear of retaliation, is that the resistance movement has generated a stigma. “They told us that we are illegal miners and that we do not want legality because we want to return to what is illegal. But this is false,” the resident said.

Natalia Bonilla, from the organization Acción Ecológica, says that when her organization began to work with the residents, they realized that the portrayal of the community members as illegal miners was not truthful. “It is a community of farmers, ranchers and agricultural people that was invaded by illegal miners. They marked them as illegal miners and made them invisible,” Bonilla said.

Favio Ocampo is the head of operations of Hanrine Ecuadorian Exploration and Mining S.A., the company that holds the mining titles and is a subsidiary of Australian company Hancock Prospecting. Ocampo said in an interview with Primicias, an Ecuadoran media outlet, that “there is a group of residents of La Merced de Buenos Aires that is polluting with illegal mining and that is now disguising itself as an anti-mining group. This group has taken the entrance to La Merced de Buenos Aires, claiming that the town is against legal and illegal mining, but they are the same [ones who] have legal proceedings against them for illegal mining.”

This is where the issue becomes more complicated. Using the argument that the opposing residents who are blocking the company’s entry into the land are illegal miners, Hanrine has launched civil and criminal actions against several people from the community, including some local authorities. “We are going through five criminalization proceedings. They are doing this to undermine the resistance of this peaceful protest that we’ve had since April 19,” said another resident of the area who asked not to be named. “The latest thing they have accused us of is unlawful association. They have even accused the president of the decentralized autonomous government [GAD] of the rural parish of Buenos Aires.”

Yuly Tenorio is a lawyer specializing in the environment who says that while some people denounced by the company may be linked to illegal mining, the vast majority are defenders of the territory who are being persecuted. This is why she has decided to defend them. According to Tenorio, Hanrine has denounced about 70 people from the area, including several Awá Indigenous people from the Palmira community who live in the forests of Buenos Aires and oppose mining.

“Not everyone has received notice because they live in very remote areas, and the Awá do not have a stable territory. Many of them do not even have a form of identification,” Tenorio said.

The five legal processes are in the pretrial investigation phase. Three of the proceedings are for alleged damage to property, one is for intimidation, and the last is for alleged unlawful association.

“The company is denouncing them via criminal and civil action to recover the alleged money that it has lost due to citizen resistance,” Tenorio said. “The objective is for the community to exhaust themselves by hiring lawyers for their defense instead of dedicating themselves to protecting their territory, requesting information, or precautionary measures.”

Ocampo said Hanrine has attempted to enter one of its mining concessions, called “Imba 1,” for several months, “but our attempts have been blocked by these people who have taken the entrance of the parish of La Merced de Buenos Aires, within full view of the police.”

“All the people in our favor and who work with us, or who provide any type of service to us, have been injured, intimidated, and threatened,” he added.

The tension between the community and the company has escalated to new levels. On April 21 this year, the Ombudsman’s Office said in a public announcement that the government will be responsible for the criminal proceedings of the Buenos Aires community leaders and those who are defending human rights and the rights of nature.

When contacted by Mongabay Latam, ombudsman Edwin Piedra confirmed that criminal proceedings have been initiated that are in the domain of the Prosecutor’s Office and are under investigation. But he added that “the Ombudsman’s Office hopes that the requests will be considered and that the prosecutor’s office will archive the proceedings, since those who exercise the right to resist cannot be penalized for common crimes like unlawful association and other types of criminal offenses, which can serve to threaten and harass people and therefore hinder their defense work.”

Lack of environmental and prior consultations

While the conflict between the residents and the mining company continues, illegal mining in the area has left damage that has not yet been fully evaluated. The only concrete data so far comes from a report by Ecuador’s Ministry of Environment and Water (MAAE) at the time of the Radiant Dawn operation. The report says 54.38 hectares (about 134 acres) of deforestation was found, along with changes to water flows, inadequate management of solid waste, and changes in water and soil quality.

More than two years since the removal of the thousands of illegal miners, it’s still not clear who will be held responsible for this damage and for rehabilitating the environment. The Ecuadoran government has not conducted an in-depth analysis, and the mining company hasn’t accepted responsibility for these costs within its concession.

Ocampo said Hanrine takes no responsibility for the damage already done.

“The government needs to take action,” he said. “We have not received any report by experts from the government about the calculation of the environmental damage. It is not the responsibility of Hanrine. Once the expert report is done, the government should identify those who are responsible.” They know who they are, he added, and they should prosecute them, because the people who profit from the illegal mining remain free.

The company says it has the right to enter its mining concessions to continue its advanced prospecting for copper. However, the difficult socioenvironmental conflict that exists in Buenos Aires complicates the situation.

The community says the company has never publicized the mining project and that neither they nor the Awá Indigenous people participated in an environmental consultation or a free and informed prior consultation. Piedra says government institutions should have sufficiently informed the community about the consultation processes that would have been conducted, and that they permitted the acquisition of environmental permissions for the concessions. “It is the responsibility of the government to comply with this obligation before granting concessions and permissions,” Piedra said.

Mongabay Latam contacted the MAAE to learn whether there was an environmental consultation but did not receive a response by the time of this article’s publication in Spanish.

No access to information

Access to information has also been an obstacle for the Buenos Aires community. According to several residents interviewed by Mongabay Latam, the company has told them it does not need to show documentation to them, so they have had to make formal requests to government entities. These entities have delayed their responses or not given complete answers, arguing that the information being sought is sensitive in nature.

“We still do not know the environmental management plans or whether environmental impact studies exist that are not a copy of other studies,” Tenorio said. Mongabay Latam also asked the MAAE whether it had granted environmental permits to Hanrine but did not receive a response.

The Ombudsman’s Office said it was “urging the Ministry of Environment and Water, the Ministry of Energy and Non-Renewable Natural Resources, and the Agency of Regulation and Control of Energy and Non-Renewable Natural Resources not to grant environmental permits or mining concessions until they proceed with the integral repair of the rights of nature, due to the existence of environmental liabilities, and they must begin the necessary measures for the restoration of nature.”

Buenos Aires community leaders say they hope for a popular consultation to prohibit mining in their territory. On May 10, some residents who want to ban both illegal and legal mining requested precautionary measures before the constitutional judge for the province of Imbabura, Manuel Mesías Sarmiento, to guarantee the removal of the camps that Hanrine has set up in public areas, and the prohibition of the entrance of heavy machinery and any other vehicles owned by the company.