by DGR News Service | Dec 17, 2021 | Biodiversity & Habitat Destruction, Climate Change, Colonialism & Conquest, Human Supremacy, The Problem: Civilization, The Solution: Resistance

This article was produced by Local Peace Economy, a project of the Independent Media Institute.

By Koohan Paik-Mander

The U.S. military is famous for being the single largest consumer of petroleum products in the world and the largest emitter of greenhouse gases. Its carbon emissions exceed those released by “more than 100 countries combined.”

Now, with the Biden administration’s mandate to slash carbon emissions “at least in half by the end of the decade,” the Pentagon has committed to using all-electric vehicles and transitioning to biofuels for all its trucks, ships and aircraft. But is only addressing emissions enough to mitigate the current climate crisis?

What does not figure into the climate calculus of the new emission-halving plan is that the Pentagon can still continue to destroy Earth’s natural systems that help sequester carbon and generate oxygen. For example, the plan ignores the Pentagon’s continuing role in the annihilation of whales, in spite of the miraculous role that large cetaceans have played in delaying climate catastrophe and “maintaining healthy marine ecosystems,” according to a report by Whale and Dolphin Conservation. This fact has mostly gone unnoticed until only recently.

There are countless ways in which the Pentagon hobbles Earth’s inherent abilities to regenerate itself. Yet, it has been the decimation of populations of whales and dolphins over the last decade—resulting from the year-round, full-spectrum military practices carried out in the oceans—that has fast-tracked us toward a cataclysmic environmental tipping point.

The other imminent danger that whales and dolphins face is from the installation of space-war infrastructure, which is taking place currently. This new infrastructure comprises the development of the so-called “smart ocean,” rocket launchpads, missile tracking stations and other components of satellite-based battle. If the billions of dollars being plowed into the 2022 defense budget for space-war technology are any indication of what’s in store, the destruction to marine life caused by the use of these technologies will only accelerate in the future, hurtling Earth’s creatures to an even quicker demise than already forecast.

Whale Health: The Easiest and Most Effective Way to Sequester Carbon

It’s first important to understand how whales are indispensable to mitigating climate catastrophe, and why reviving their numbers is crucial to slowing down damage and even repairing the marine ecosystem. The importance of whales in fighting the climate crisis has also been highlighted in an article that appeared in the International Monetary Fund’s Finance and Development magazine, which calls for the restoration of global whale populations. “Protecting whales could add significantly to carbon capture,” states the article, showing how the global financial institution also recognizes whale health to be one of the most economical and effective solutions to the climate crisis.

Throughout their lives, whales enable the oceans to sequester a whopping 2 billion metric tons of carbon dioxide per year. That astonishing amount in a single year is nearly double the 1.2 billion metric tons of carbon that was emitted by the U.S. military in the entire 16-year span between 2001 and 2017, according to an article in Grist, which relied on a paper from the Costs of War Project at Brown University’s Watson Institute.

The profound role of whales in keeping the world alive is generally unrecognized. Much of how whales sequester carbon is due to their symbiotic relationship with phytoplankton, the organisms that are the base of all marine food chains.

The way the sequestering of carbon by whales works is through the piston-like movements of the marine mammals as they dive to the depths to feed and then come up to the surface to breathe. This “whale pump” propels their own feces in giant plumes up to the surface of the water. This helps bring essential nutrients from the ocean depths to the surface areas where sunlight enables phytoplankton to flourish and reproduce, and where photosynthesis promotes the sequestration of carbon and the generation of oxygen. More than half the oxygen in the atmosphere comes from phytoplankton. Because of these infinitesimal marine organisms, our oceans truly are the lungs of the planet.

More whales mean more phytoplankton, which means more oxygen and more carbon capture. According to the authors of the article in the IMF’s Finance and Development magazine—Ralph Chami and Sena Oztosun, from the IMF’s Institute for Capacity Development, and two professors, Thomas Cosimano from the University of Notre Dame and Connel Fullenkamp from Duke University—if the world could increase “phytoplankton productivity” via “whale activity” by only 1 percent, it “would capture hundreds of millions of tons of additional CO2 a year, equivalent to the sudden appearance of 2 billion mature trees.”

Even after death, whale carcasses function as carbon sinks. Every year, it is estimated that whale carcasses transport 190,000 tons of carbon, locked within their bodies, to the bottom of the sea. That’s the same amount of carbon produced by 80,000 cars per year, according to Sri Lankan marine biologist Asha de Vos, who appeared on TED Radio Hour on NPR. On the seafloor, this carbon supports deep-sea ecosystems and is integrated into marine sediments.

Vacuuming CO2 From the Sky—a False Solution

Meanwhile, giant concrete-and-metal “direct air carbon capture” plants are being planned by the private sector for construction in natural landscapes all over the world. The largest one began operation in 2021 in Iceland. The plant is named “Orca,” which not only happens to be a type of cetacean but is also derived from the Icelandic word for “energy” (orka).

Orca captures a mere 10 metric tons of CO2 per day—compared to about 5.5 million metric tons per day of that currently sequestered by our oceans, due, in large part, to whales. And yet, the minuscule comparative success by Orca is being celebrated, while the effectiveness of whales goes largely unnoticed. In fact, President Joe Biden’s $1 trillion infrastructure bill contains $3.5 billion for building four gigantic direct air capture facilities around the country. Nothing was allocated to protect and regenerate the real orcas of the sea.

If ever there were “superheroes” who could save us from the climate crisis, they would be the whales and the phytoplankton, not the direct air capture plants, and certainly not the U.S. military. Clearly, a key path forward toward a livable planet is to make whale and ocean conservation a top priority.

‘We Have to Destroy the Village in Order to Save It’

Unfortunately, the U.S. budget priorities never fail to put the Pentagon above all else—even a breathable atmosphere. At a December 2021 hearing on “How Operational Energy Can Help Us Address Logistics Challenges” by the Readiness Subcommittee of the U.S. House Armed Services Committee, Representative Austin Scott (R-GA) said, “I know we’re concerned about emissions and other things, and we should be. We can and should do a better job of taking care of the environment. But ultimately, when we’re in a fight, we have to win that fight.”

This logic that “we have to destroy the village in order to save it” prevails at the Pentagon. For example, hundreds of naval exercises conducted year-round in the Indo-Pacific region damage and kill tens of thousands of whales annually. And every year, the number of war games, encouraged by the U.S. Department of Defense, increases.

They’re called “war games,” but for creatures of the sea, it’s not a game at all.

Pentagon documents estimate that 13,744 whales and dolphins are legally allowed to be killed as “incidental takes” during any given year due to military exercises in the Gulf of Alaska.

In waters surrounding the Mariana Islands in the Pacific Ocean alone, the violence is more dire. More than 400,000 cetaceans comprising 26 species were allowed to have been sacrificed as “takes” during military practice between 2015 and 2020.

These are only two examples of a myriad of routine naval exercises. Needless to say, these ecocidal activities dramatically decrease the ocean’s abilities to mitigate climate catastrophe.

The Perils of Sonar

The most lethal component to whales is sonar, used to detect submarines. Whales will go to great lengths to get away from the deadly rolls of sonar waves. They “will swim hundreds of miles… and even beach themselves” in groups in order to escape sonar, according to an article in Scientific American. Necropsies have revealed bleeding from the eyes and ears, caused by too-rapid changes in depths as whales try to flee the sonar, revealed the article.

Low levels of sonar that may not directly damage whales could still harm them by triggering behavioral changes. According to an article in Nature, a 2006 UK military study used an array of hydrophones to listen for whale sounds during marine maneuvers. Over the period of the exercise, “the number of whale recordings dropped from over 200 to less than 50,” Nature reported.

“Beaked whale species… appear to cease vocalising and foraging for food in the area around active sonar transmissions,” concluded a 2007 unpublished UK report, which referred to the study.

The report further noted, “Since these animals feed at depth, this could have the effect of preventing a beaked whale from feeding over the course of the trial and could lead to second or third order effects on the animal and population as a whole.”

The report extrapolated that these second- and third-order effects could include starvation and then death.

The ‘Smart Ocean’ and the JADC2

Until now, sonar in the oceans has been exclusively used for military purposes. This is about to change. There is a “subsea data network” being developed that would use sonar as a component of undersea Wi-Fi for mixed civilian and military use. Scientists from member nations of the Institute of Electrical and Electronics Engineers (IEEE), including, but not limited to Australia, China, the UK, South Korea and Saudi Arabia, are creating what is called the “Internet of Underwater Things,” or IoUT. They are busy at the drawing board, designing data networks consisting of sonar and laser transmitters to be installed across vast undersea expanses. These transmitters would send sonar signals to a network of transponders on the ocean surface, which would then send 5G signals to satellites.

Utilized by both industry and military, the data network would saturate the ocean with sonar waves. This does not bode well for whale wellness or the climate. And yet, promoters are calling this development the “smart ocean.”

The military is orchestrating a similar overhaul on land and in space. Known as the Joint All-Domain Command and Control (JADC2), it would interface with the subsea sonar data network. It would require a grid of satellites that could control every coordinate on the planet and in the atmosphere, rendering a real-life, 3D chessboard, ready for high-tech battle.

In service to the JADC2, thousands more satellites are being launched into space. Reefs are being dredged and forests are being razed throughout Asia and the Pacific as an ambitious system of “mini-bases” is being erected on as many islands as possible—missile deployment stations, satellite launch pads, radar tracking stations, aircraft carrier ports, live-fire training areas and other facilities—all for satellite-controlled war. The system of mini-bases, in communication with the satellites, and with aircraft, ships and undersea submarines (via sonar), will be replacing the bulky brick-and-mortar bases of the 20th century.

Its data-storage cloud, called JEDI (Joint Enterprise Defense Infrastructure), will be co-developed at a cost of tens of billions of dollars. The Pentagon has requested bids on the herculean project from companies like Microsoft, Amazon, Oracle and Google.

Save the Whales, Save Ourselves

Viewed from a climate perspective, the Department of Defense is flagrantly barreling away from its stated mission, to “ensure our nation’s security.” The ongoing atrocities of the U.S. military against whales and marine ecosystems make a mockery of any of its climate initiatives.

While the slogan “Save the Whales” has been bandied about for decades, they’re the ones actually saving us. In destroying them, we destroy ourselves.

Koohan Paik-Mander, who grew up in postwar Korea and in the U.S. colony of Guam, is a Hawaii-based journalist and media educator. She is a board member of the Global Network Against Weapons and Nuclear Power in Space, a member of the CODEPINK working group China Is Not Our Enemy, and an advisory committee member for the Global Just Transition project at Foreign Policy in Focus. She formerly served as campaign director of the Asia-Pacific program at the International Forum on Globalization. She is the co-author of The Superferry Chronicles: Hawaii’s Uprising Against Militarism, Commercialism and the Desecration of the Earth and has written on militarism in the Asia-Pacific for the Nation, the Progressive, Foreign Policy in Focus and other publications.

Banner image: flickr (CC BY-NC-ND 2.0)

by DGR News Service | Dec 1, 2021 | Biodiversity & Habitat Destruction, Climate Change, Human Supremacy, The Problem: Civilization

This article first appeared in The Revelator.

Editor’s note: It would seem like these rights would be self evident birth rights unrequiring of institutions agency. Unfortunately like all UN resolutions this carries no enforcement, see Palestine. How can enviromental justice come about? Rich nations must stop outsourcing their luxury lifestyle. This does not mean NIMBY Not In My Back Yard, it means NOPE Not On Planet Earth.

By Steve Trent

In October the UN Human Rights Council voted to recognize the right to a safe, clean, healthy and sustainable environment as a human right. Notable among the dissenting voices was the United Kingdom, which eventually begrudgingly voted in favor, while stressing the fact that no country would be legally bound to the resolution’s terms. Four member states — China, India, Japan and Russia — abstained.

This resolution was long overdue. Air pollution alone kills an estimated 7 million people every year, according to the World Health Organization. Yet the resolution doesn’t go nearly far enough: It’s not legally binding, as the U.K. was keen to point out, nor has it been incorporated into any of the 70-plus human-rights treaties that the Universal Declaration of Human Rights has inspired.

Moreover, this issue goes beyond the concept of a safe, sustainable environment as a single human right. The fact is that all our most fundamental human rights rely on thriving natural systems — from the right to adequate food to a livelihood worthy of human dignity and even the right to life.

Speaking after the resolution was made, UN High Commissioner for Human Rights Michelle Bachelet said: “[This is] about protecting people and planet — the air we breathe, the water we drink, the food we eat. It is also about protecting the natural systems which are basic preconditions to the lives and livelihoods of all people, wherever they live.”

She’s right. And yet across the world, the twin biodiversity and climate crises are coming together to form a full-blown human-rights emergency.

Climate

Fires, floods and storms are ravaging the world, growing in severity as global heating escalates. Over the past two years, unprecedented fires in Australia, Canada, the Mediterranean, Brazil, the United States and other countries have devastated homes and communities, leaving destitution and death in their wake.

In the record-breaking 2020 hurricane season, Hurricane Eta was followed under two weeks later by Hurricane Iota, together affecting more than 7.5 million people in Central America and leaving at least 200 dead. Nor are the impacts restricted to sudden-onset disasters. After a fourth year of drought, Madagascar is currently experiencing world’s first “climate change famine” with more than one million people now in need of emergency food aid.

The climate crisis is already seriously undermining human rights around the world, directly destroying people’s homes and livelihoods, and taking lives. But it is also a threat multiplier, compounding existing economic, political, and social stresses and driving a rising likelihood of violent conflict.

The Coast Guard supporting humanitarian assistance and disaster relief operations in Honduras after Hurricane Eta. Photo: U.S. Coast Guard, (CC BY-NC-ND 2.0)

Ecosystems

Alongside this grim reality, the world is facing its sixth mass extinction — this time human-caused — with the rate of species extinction already at tens to hundreds of times higher than over the past 10 million years. In 2020, the UN Convention on Biological Diversity reported that we had missed all 20 targets set to bring biodiversity loss to a halt.

Again, this puts human rights at risk. For example, as we empty our ocean of marine life through destructive and illegal fishing, coastal communities are losing not only their livelihoods but also essential food security as vital protein becomes more and more scarce. In a recent investigation, we found that basic human rights of Ghana’s fishing communities, including the right to adequate food, adequate standard of living and just working conditions, are under threat because of the government’s failure to tackle overfishing and illegal fishing by foreign-owned industrial trawlers. Over half of the 215 canoe fishers, processors and traders we spoke to reported going without sufficient food over the past year.

And of course, the COVID-19 pandemic represents the latest tragedy to emerge from our rampant exploitation of the natural world. As ecological degradation accelerates, animals that wouldn’t mix closely in the wild are brought into close contact with other species — and with humans. These conditions are perfect for the emergence of new and deadly viruses.

Injustice

Weaving through these crises and tragedies is the fact that the world’s poorest and most vulnerable communities invariably pay the highest price. This is an environmental injustice.Global heating has led to a 25% increase in inequality between countries over the past half century, as hotter, poorer countries tend to suffer the most from the actions of cooler, richer ones. The World Bank estimates that the COVID-19 pandemic pushed some 97 million vulnerable people into poverty in 2020.

At the same time, we’ve seen examples of initiatives, some perhaps well meaning, driving local communities, Indigenous peoples and the poor from traditional areas in the name of conservation or so-called protected areas. Such initiatives often completely disregard the importance of historic lands to the culture, history and well-being of communities. In our efforts to protect and restore our natural world, we must prevent this abuse of basic human rights and recognize the contribution that these communities have made and can make to genuinely effective conservation.

Equity and fairness are scarce in a world where the fundamental concepts of environmental justice are ignored, denied and circumvented.

Achieving true environmental justice and ending the twin crises of biodiversity and climate breakdown requires us to reassess our connection to nature and to recognize once and for all that humanity doesn’t exist outside the natural world.

We must make the right to a safe, clean, healthy and sustainable environment a universal, legally binding human right, starting with the UN codifying this new declaration into existing treaties, then making it legally binding on the national and international level. We are entirely dependent on nature for our most basic needs and fundamental human rights, and we all have a role to play in nurturing and protecting it.

The opinions expressed above are those of the author and do not necessarily reflect those of Deep Green Resistance, The News Service or its staff.

by DGR News Service | Nov 28, 2021 | Building Alternatives, Climate Change, Culture of Resistance, Human Supremacy, The Problem: Civilization, Toxification

A very typical response to my writing can be summarized as: “But… cities?!?” How are we going to fit cities into this future world? My feeling is that we can’t. Mostly.

I’ve never explicitly said that cities are not optimal, but I think it’s fairly obvious what my biases are. I will be honest, I don’t like urban environments. I don’t like the noise. I don’t like the smell. I don’t like the mess. Just everywhere mess! I’m not fond of the pace or the congestion. In 24-hour places like New York City, I can’t sleep. I am generally uncomfortable (translate: nauseous) in structures that I can feel moving, and I can feel the sway in tall buildings. I absolutely hate elevators. In the city, one can’t have goats. Rarely chickens. There’s no horizon. Few healthy old trees. Utterly insufficient gardens. And there are no stars.

Now, I know there are cities that are not this bad. Or I know one, anyway. Albuquerque is a city of about 750,000 people with maybe a half dozen moderately tall buildings downtown. Yet it’s not too horizontally sprawling, being held in check by mountains and volcanoes and Indigenous lands. And a water supply that is strictly tied to the river valley. But within the city, there are many farms and gardens and a wide wetlands, the bosque, along the banks of the Rio Grande. Chickens and goats and alpacas are everywhere (except in the Rio Rancho suburb, which is also the ugliest, sprawling-est part of New Mexico). The skies are brilliant all day, all night, all through the year. You can go wandering at 2am and feel safe. Nothing is open past 10pm, so apart from a sporadic teen in a loud car, it’s quiet. Sleepy even. There is never a rush. It’s called the land of mañana only somewhat jokingly. It is also a place where everyone knows everyone else; it’s the largest small town in the world. And it smells like chile, rain on parched earth, cedar smoke, and sage brush. With the odd dash of manure…

So cities can be accommodating places. It depends on the people, I suppose. Burqueans are Westerners — laconic and lazy and not terribly interested in your issues. But I haven’t been in many cities like that. And maybe Albuquerque doesn’t actually count as a city. There are horse hitches outside buildings. With hitched horses.

But my preferences are hardly average nor all that important. What is important is that cities make no ecological or biophysical sense. And to get out of this mess we need to bring our living back within the realm of good sense.

I could begin by pointing to the ridiculously fragile locations of many of the largest urban centers. No amount of techno-magical thinking is going to keep Boston above water. Or New York. Or Miami. I could fill pages with that list. Then add on those that might be marginally above water but currently rely upon groundwater or coastal rivers for drinking water — which will be contaminated with seawater long before the streets turn into canals. Ought to toss extreme fire danger onto the list also, taking out much of California, Greece, perhaps most of the Australian continent. And then there’s Phoenix which may quite literally run out of water. Of course, many other US Sunbelt cities — including Albuquerque — are going to discover that a desert location can not, by definition, provide water for millions of people. Once fossil groundwater is pumped dry (in about, oh, ten years…) there won’t be water coming out of the taps. Same goes for most of the cities in the two bands around 25-30° latitude away from the equator that get little moisture because planetary air flow is uncooperative (though this may change… in ways that might be good… maybe). Then there’s just pure heat. Adding a degree or so to the global average — which is inevitable at the current level of greenhouse gas concentration in the atmosphere even if we were to miraculously stop emissions today — will turn urban areas that are merely hot now into uninhabitable ovens, with atmospheric heat magnified by urban heating. Just for completeness, there are quite a few places that will simply collapse as ground water is depleted or as permafrost melts. Oh, and then there’s Detroit and other urban disaster zones — places so completely degraded by industrial mess-making that soil, water and air in these locations will be toxic to most life-forms for many human generations. So. Yeah. There are problems.

Let’s give it a different framing. There are large areas — most of which contain large cities — in which property is no longer insurable for at least one type of disaster. You can’t buy flood insurance in broad swaths of New Jersey or Florida. You can’t buy fire insurance in Orange County, California. Some actuary — a person whose job is calculating odds and putting a monetary value on risk — has determined that the odds are not in your favor. Full stop. More precisely the probability of an insurance claim paid by the company being greater than all the money you pay that company to buy the insurance is too high for the company to even begin taking your money. (And they really want to take your money!) There will be a disaster that creates a claim, and it will happen before you can pay much into your policy. Best you open a bank account and start dumping all your paychecks in there because that’s what it will cost to live in these uninsurable areas. (Though for now in this country, taxpayers are serving as the bank account for the most costly uninsurable properties.)

The risk of a flood happening in New Jersey is so high and immediate that you (and the insurance industry) can count on having a flooded house. And there are many houses that will be flooded. New Jersey is a densely populated region, especially so where risk of flood is greatest. This is not an anomaly. New Jersey is not unusually silly in siting urban areas. The urban areas in New Jersey grew up near water, rather than in a less flood-prone area further inland, just as urban areas grow near water everywhere else in the world — because water makes for easy transport of large volumes of stuff, lowering the costs of trade. There is and always was risk of flooding in these urban areas. But the floods happened infrequently before ocean warming made energetic storms that could throw large volumes of water up on the coast a regular — and predictable — occurrence. The same sort of calculations can be made for fire, for structural damages and I would imagine for sheer uninhabitability — though I doubt actuaries will have much to say about that. There are no insurance policies for putting property where humans simply can’t survive.

Because we’re supposed to be smarter than that. No, we’re supposed to be above all that, able to engineer our way forward in any unfavorable circumstance. (Witness the “let’s move to Mars” idiocy.) And in much urban development it’s not even about overcoming the likely risks. Risk-prone and degraded properties are developed by corporations who have no intention of owning the property long term. They build structures and sell those “improved properties” to others as quickly as they can. If they even bother to investigate the risks of living in that area, they don’t broadcast that information. They often take steps to conceal any qualities in a property that will lower the sale price. This is such a commonplace it’s a clichéd plot point in movies and novels.

Cities are located in the best places to move goods around and in the easiest, cheapest places to develop property for sale. This last is more a feature of former colonies which made wealth through this process of appropriating, “improving” and selling land. In the hearts of former empires, cities existed before wealth extraction turned to development of land. But a good number of them have caught up with their former colonies. Los Angeles has nothing on London sprawl. This method of making money — acquire, build and sell quickly at the highest profit — will necessarily create concentrated development in places that historically were either farmland or empty land. In the latter case, there were reasons that humans had not built things there. Many of those reasons were ecological. It made no sense to put a structure there, let alone a whole city of them. But empty lands are cheapest to develop, so the reasons were ignored. Wetlands were drained. Forests were cleared. Grasslands were paved over. Wells were drilled deep into desert rock to pull up the remnants of the last glacial meltwaters. Homes and businesses were plopped onto newly laid roads with no concern for long term durability. That was the point of building in this way. If the costs of locating structures in ecologically sustainable places were paid, then there would be no profit. So the last few hundred years has seen cities grow in places where they would always be under threat from natural processes and in fact magnify those threats by ignoring them. By cutting those costs.

But then cities have never been great. They’re good for concentrating and controlling the labor pool. That’s it. A city is now and always has been a warehouse for laborers. It is the cheapest warehouse. People are packed into cities with no accommodation for their actual lives. No space for anything. No way to produce anything except through market mechanisms of centralized production. This is by design. Because the laborers are also the market. If they are meeting their own needs, they aren’t buying stuff. Cities are very good at stripping all agency from a large group of humans, making them completely dependent on the market for every need. You can’t sneeze in a city without it profiting someone who is not you. And you can’t even begin to feed or house or clothe yourself. There are no resources for you to do any of this in a city.

Cities may be marginally better at leveraging concentrated capital into cultural institutions than a more dispersed settlement pattern. Maybe. Not that rich folk won’t fund their favorite arts wherever they live. Witness the magnificent theatre, music, and visual arts thriving in the wilds of Western Massachusetts. But cities absolutely suck at meeting our biophysical needs — from food to companionship to a non-toxic environment. Call me what you will, but when the choice is between a secure food supply and cultural attractions, I’m going with food.

Some people have noted this conflict between urban living and actual living. There are efforts to clean up the toxic messes we’ve created (created, again, by design… toxicity happens because business will not pay the full costs of doing things safely and cleanly). There are urban gardens sprouting in empty lots. There are calls for less car traffic and more travel by bike and foot. There is a return to the idea of neighborhood. People are attempting to meet their physical and emotional needs within the structures of a city. I am not sure any of this is going to work. Because that is not how a city works.

A city works by depriving most of its inhabitants of the means to meet their basic needs, forcing them to work for wages so that they can buy those needs and produce profits. That is what cities are designed for and that is what they do best. There is not even the space in a city to allow its citizens to provide for themselves. Everything must be produced elsewhere and shipped into the city. And shipping is increasingly a problem both because we have to stop spewing greenhouse gases into the atmosphere and because it is increasingly expensive to acquire fossil fuels. All the plans I’ve seen so far do not address this basic problem.

Here is one example: vertical gardens, growing food in a tower to maximize growing area but minimize the horizontal footprint so that a “farm” will fit within the confines of a city. I don’t think these are well conceived. Half a minute’s thought on what actually goes into growing healthy plants reveals several fatal flaws in the design. Attempts to produce food where there is no soil, where water has to be pumped, and where sunlight has to be synthesized with electricity are costly if not futile. And all these tools and raw materials still have to be sourced and produced elsewhere and then shipped in. It may be that we use more resources in building a vertical farm than if we just grew a real farm. And we won’t be producing very much food in this resource-sucking system. We may be able to grow some leafy vegetables, but those vegetables will be lacking in nutrition relative to food grown in a living ecosystem. There isn’t even space for grains and pulses in a vertical garden unless it’s very vertical. Which seems expensive. Not a project we’re going to be able to maintain in a contracting economy that is generally out of resources.

Even if it were not expensive though, vertical farming is not producing food. Synthesizing a growing environment will always fail because we can’t make living systems, and that’s what is needed to grow food. Human attempts to manufacture biology fail because we don’t fully understand how biology works and maybe can’t know being embedded within biology. Further, I suspect most synthesized foods will not meet human nutrition needs even if all the building blocks we know about are included. There are emergent properties and interdependencies and entanglements that we can’t begin to understand, never mind create. The chemical compounds in a berry do not make a berry. A berry is a particular arrangement of its chemical composition along with a large number of microbes and other non-berry materials all of which make up the nutritional content of the berry when you pop the whole living thing in your mouth. And we don’t know what of all that berry and non-berry stuff is essential to our digestive tract to turn that berry into food for our cells. We can’t make a berry because we don’t know what a berry is. What we do know is that it is always more than the sum of its broken down parts. And that is what synthesizing is, a sum of brokenness.

But these ideas keep manifesting because we think rather highly of ourselves. We believe that we can engineer our way over any problem. We really haven’t done that though. We’ve thrown a huge wealth of the planet’s energy and resources into creating this style of living. Our technologies are useless without that resource flow. Just as importantly, our technologies are useless at containing the waste flowing out of that system. And most importantly, our technologies are designed to work within a profit-driven system. When that breaks down, when there is no profit, there is no technology. We aren’t going to put scarce resources and effort into maintaining the tools; we’ll produce what we need directly at scales that don’t require those costly tool systems.

And that’s the main reason I believe that we will be abandoning cities. They will break down. They are a technology that only works while there are abundant resources, while there is capacity for waste absorption, and while there are profits to be made on all those flows. We aren’t going to put effort into maintaining this tool if it no longer serves us. We won’t have the time or the wherewithal. We will need to produce what we need to live.

Some are bemoaning the idea of humans dispersing into the countryside. And maybe that’s a problem if those dispersed humans are also bringing along their wasteful, resource-sucking lifestyles. But I’m not sure that will be possible. There won’t be resources to waste or suck. Not only that, but most people are not inclined toward messing up their own homes. Degradation of the land happens when those resources are sucked out of the land to be used by people living elsewhere. Humans have lived in dispersed settlement patterns, integrated within our ecosystems, for a very long time, much longer than we’ve been “civilized”. This idea that we need to set aside places for wilderness comes from the idea that humans are not part of this world. That humans are above nature and generally destructive of nature. That humans uniquely have the potential to transcend nature and invent their way toward meeting biophysical needs independent of nature. None of this is in any way real. Putting a lot of humans in a confined space will not magically rewild the rest of the world. We will still be sucking those resources. More resources than if we lived in a place where we didn’t need to maintain an artificial living environment through transport and tools. More resources than if we lived within the carrying capacity of the lands we fully inhabit — as we have for most of our existence.

And make no mistake, the land is going to see that we do that. This is what is happening. We have exceeded carrying capacity at all scales. There are mechanisms in living systems that prevent this. We are experiencing those mechanisms. We are experiencing the consequences of exceeding carrying capacity for the planet. This will be fixed. And it will be completely out of our hands. Cities will be abandoned because we will be dealing with all the consequences of cities and returning to a way of living that we know works within nature. Lots of smallish towns and settlements surrounded by and interpenetrated with land that can produce our needs.

I suspect our urban centers will be very much like Albuquerque…

Banner image by Ron Reiring at Flickr. (CC BY 2.0)

![Electric Vehicles: Back to the Future? [Part 2/2]](https://dgrnewsservice.org/wp-content/uploads/sites/18/2021/11/Illustration_017.jpg)

by DGR News Service | Nov 21, 2021 | Climate Change, Mining & Drilling, The Problem: Civilization

By Frédéric Moreau

Read Part 1 of this article here.

While the share of solar and wind power is tending to increase, overall energy consumption is rising from all sources — development, demography (a taboo subject that has been neglected for too long), and new uses, such as digital technology in all its forms (12% of the electricity consumed in France, and 3% worldwide, a figure that is constantly rising, with digital technology now emitting more CO2 than air transport⁴⁴). Digital technology also competes with vehicles, especially electric ones, in terms of the consumption of metals and rare earths. This is perfectly logical since the renewable energy industry, and to a lesser extent the hydroelectric industry (dams), requires oil, coal and gas upstream to manufacture the equipment. Solar panels look indeed very clean once installed on a roof or in a field and which will later produce so-called “green” electricity.

We almost systematically forget, for example, the 600 to 1,500 tons of concrete for the wind turbine base, often not reused (change of model or technology during its lifespan, lack of financing to dismantle it, etc.), which holds these towers in place. Concrete that is also difficult to recycle without new and consequent energy expenditures, or even 5,000 tons for offshore wind turbines⁴⁵. Even hydrogen⁴⁶, which inveterate techno-futurists are now touting as clean and an almost free unlimited energy of tomorrow, is derived from natural gas and therefore from a fossil fuel that emits CO2. Because on Earth, unlike in the Sun, hydrogen is not a primary energy, i.e. an energy that exists in its natural state like wood or coal and can be exploited almost immediately. Not to mention that converting one energy into another always causes a loss (due to entropy and the laws of thermodynamics; physics once again preventing us from dreaming of the mythical 100% clean, 100% recyclable and perpetual motion).

Consequently oil consumption, far from falling as hoped, has instead risen by nearly 15% in five years from 35 billion barrels in 2014 to 40 billion in 2019⁴⁷. Moreover, industry and services cannot resign themselves to the randomness of the intermittency inherent in renewable energies. We cannot tell a driver to wait for the sun to shine or for the wind to blow again, just as the miller in bygone days waited for the wind to grind the wheat, to charge the batteries of his ZOE. Since we can hardly store it in large quantities, controllable electricity production solutions are still essential to take over.

Jean-Marc Jancovici⁴⁸, an engineer at the École des Mines, has calculated that in order to charge every evening for two hours the 32 million electric cars, that will replace the 32 million thermal cars in the country⁴⁹, the current capacity of this electricity available on demand would have to be increased sevenfold from 100GW to 700GW. Thus instead of reducing the number of the most polluting installations or those considered rightly or wrongly (rather rightly according to the inhabitants of Chernobyl, Three Miles Island and Fukushima) potentially dangerous by replacing them with renewable energy production installations, we would paradoxically have to increase them. These “green” facilities are also much more material-intensive (up to ten times more) per kWh produced than conventional thermal power plants⁵⁰, especially for offshore wind turbines which require, in addition to concrete, kilometers of additional large cables. Moreover the nuclear power plants (among these controllable facilities) cooling, though climate change, are beginning to be made problematic for those located near rivers whose flow is increasingly fluctuating. And those whose water, even if it remains abundant, may be too hot in periods of heat wave to fulfill its intended purpose, sometimes leading to their temporary shutdown⁵¹. This problem will also be found with many other power plants, such as those located in the United States and with a number of hydroelectric dams⁵². The disappearance of glaciers threaten their water supply, as is already the case in certain regions of the world.

After this overview, only one rational conclusion can be drawn, namely that we did not ask ourselves the right questions in the first place. As the historian Bernard Fressoz⁵³ says, “the choice of the individual car was probably the worst that our societies have ever made”. However, it was not really a conscious and deliberate “choice” but a constraint imposed on the population by the conversion of the inventors/artisans of a still incipient automobile sector, whose limited production was sold to an equally limited wealthy clientele. The first cars being above all big toys for rich people who liked the thrills of real industrialists. Hand in hand with oil companies and tire manufacturers, they rationalized production by scrupulously applying Taylorist recipes and developed assembly lines such as Ford’s Model T in 1913. They then made cars available to the middle classes and over the decades created the conditions of compulsory use we know today.

Streetcars awaiting destruction. Photo: Los Angeles Times photographic archive.

It is this same trio (General Motors, Standard Oil and Firestone mainly, as well as Mack Truck and Phillips Petroleum) that was accused and condemned in 1951 by the Supreme Court of the United States of having conscientiously destroyed the streetcar networks and therefore electric public transport. They did so by taking advantage after the 1929 crash, of the “godsend” of the Great Depression, which weakened the dozens of private companies that ran them. Discredited and sabotaged in every conceivable way — including unfair competition, corruption of elected officials and high ranking civil servants, and recourse to mafia practices — streetcars were replaced first by buses, then by cars⁵⁴. This was done against a backdrop of ideological warfare, that began decades before the “official” Cold War, which an equally official History tells us about: socialist collectivism — socialist and anarchist ideas, imported at the end of the nineteenth century by immigrants from Europe and Russia, deemed subversive because they hindered the pursuit of private interests legitimized by Protestantism — countered, with the blessing of the State, by liberal individualism. This unbridled liberalism of a country crazing for the “no limits” way was also to promote the individual house of an “American dream” made possible by the private car, which explains so well the American geography of today, viable only thanks to fossil fuels⁵⁵.

Today not many people are aware of this, and very few people in the United States remember, that city dwellers did not want cars there. They were accused of monopolizing public space, blamed for their noise and bad odors. Frightened by their speed and above all they were dangerous for children who used to play in the streets. Monuments to those who lost their lives under their wheels were erected during demonstrations gathering thousands of people as a painful reminder⁵⁶. In Switzerland the canton of Graubünden banned motorized traffic throughout its territory at the beginning of the nineteenth century. It was only after quarter of a century later, after ten popular votes confirming the ban, that it was finally lifted⁵⁷.

Left: Car opposition poster for the January 18th, 1925, vote in the canton of Graubünden, Switzerland. Right: Saint-Moritz, circa 1920. Photo: Sammlung Marco Jehli, Celerina.

The dystopia feared by the English writer George Orwell in his book 1984 was in fact already largely underway at the time of its writing as far as the automobile is concerned. In fact by deliberately concealing or distorting historical truths, although they have been established for a long time and are very well documented, it is confirmed that “Who controls the past controls the future: who controls the present controls the past.” A future presented as inescapable and self-evident, which is often praised in a retroactive way, because when put in the context of the time, the reticence was nevertheless enormous⁵⁸. A future born in the myth of a technical progress, also far from being unanimously approved, in the Age of Enlightenment. The corollary of this progress would be the permanent acquisition of new, almost unlimited, material possessions made accessible by energy consumption-based mass production and access to leisure activities that also require infrastructures to satisfy them. International tourism, for example, is by no means immaterial, which we should be aware of when we get on a metallic plane burning fossil fuel and stay in a concrete hotel.

With the electric car, it is not so much a question of “saving the planet” as of saving one’s personal material comfort, which is so important today, and above all of saving the existing economic model that is so successful and rewarding for a small minority. This minority has never ceased, out of self-interest, to confuse the end with the means by equating freedom of movement with the motorization of this very movement.

The French Minister of the Economy and Finance, Bruno Le Maire declared before the car manufacturers that “car is freedom⁵⁹”. Yet this model is built at best on the syllogism, at worst on the shameless and deliberate lie of one of the founders of our modern economy, the Frenchman Jean-Baptiste. He said: “Natural resources are inexhaustible, for without them we would not obtain them for free. Since they can neither be multiplied nor exhausted, they are not the object of economic science⁶⁰“. This discipline, which claims to be a science while blithely freeing itself from the constraints of the physical environment of a finite world, that should for its part submit to its theories nevertheless by exhausting its supposedly inexhaustible resources and destroying its environment. The destruction of biodiversity and its ten-thousand-years-old climatic stability, allowed the automobile industries to prosper for over a century. They have built up veritable financial empires, allowing them to invest massively in the mainstream media which constantly promote the car, whether electric or not, placing them in the permanent top three of advertisers.

To threaten unemployment under the pretext that countless jobs depend on this automobile industry, even if it is true for the moment, is also to ignore, perhaps voluntarily, the past reluctance of the populations to the intrusion of automobiles. The people who did not perceive them at all as the symbol of freedom, prestige and social marker, even as the phallic symbol of omnipotence that they have become today for many⁶¹. It is above all to forget that until the 1920s the majority of people, at least in France, were not yet wage earners. Since wage employment was born in the United Kingdom with the industrial revolution or more precisely the capitalist revolution, beginning with the textile industry: enclosure and workhouses transformed peasants and independent artisans into manpower. Into a workforce drawn under constraint to serve the private capital by depriving them of the means of their autonomy (the appropriation of communal property). Just as imported slaves were on the other side of the Atlantic until they were replaced by the steam engine, which was much more economical and which was certainly the true abolitionist⁶². It is clear that there can be no question of challenging this dependence, which is now presented as inescapable by those who benefit most from it and those for whom it is a guarantee of social stability, and thus a formidable means of control over the populace.

Today, we are repeatedly told that “the American [and by extension Western] way of life is non-negotiable⁶³. “Sustainable development,” like “green growth,” “clean energy” and the “zero-carbon” cars (as we have seen above) are nothing but oxymorons whose sole purpose is to ensure the survival of the industries, on which this way of life relies to continue enriching their owners and shareholders. This includes the new information and communication industries that also want to sell their own products related to the car (like artificial intelligence for the autonomous car, and its potential devastating rebound effect). To also maintain the banking and financial systems that oversee them (debt and shareholders, eternally dissatisfied, demanding continuous growth, which is synonymous with constant consumption).

Cheerful passengers above flood victims queing for help, their car is shown as a source of happiness. Louisville, USA, 1937. Photo: Margaret Bourke-White, Museum of Fine Arts, Boston.

All this with the guarantee of politicians, often in blatant conflicts of interest. And all too often with the more or less unconscious, ignorant or irresponsible acceptance of populations lulled into a veritable culture of selfishness, more than reluctant from now on to consent to the slightest reduction in material comfort. Which they have been so effectively persuaded can only grow indefinitely but made only possible by the burning of long-plethoric and cheap energy. This explains their denial of the active role they play in this unbridled consumerism, the true engine of climate change. Many claim, in order to relieve themselves of guilt, to be only poor insignificant creatures that can in no way be responsible for the evils of which they are accused. And are quick to invoke natural cycles, even though they are often not even aware of them (such as the Milankovitch cycles⁶⁴ that lead us not towards a warming, but towards a cooling!), to find an easy explanation that clears them and does not question a comfortable and reassuring way of life; and a so disempowering one.

Indeed people, new Prometheus intoxicated by undeniable technical prowess, are hypersensitive to promises of innovations that look like miracle solutions. “Magical thinking”, and its avatars such as Santa Claus or Harry Potter, tends nowadays to last well beyond childhood in a highly technological society. Especially since it is exalted by the promoters of positive thinking and personal development. Whose books stuff the shelves in every bookstore, reinforcing the feeling of omnipotence, the certainty of a so-called “manifest destiny”, and the inclination to self-deification. But this era is coming to an end. Homo Deus is starting to have a serious hangover. And we are all already paying the price in social terms. The “gilets jaunes” or yellow vests in France, for example, were unable to accept a new tax on gas for funding renewables and a speed reduction on the roads from 90km/h down to 80km/h. Paying in terms of climate change, which has only just begun, from which no one will escape, rich and powerful included.

Now everyone can judge whether the electric car is as clean as we are constantly told it is, even to the point of making it, like in Orwell’s novel, an indisputable established truth, despite the flagrant contradiction in terms (“war is peace, freedom is slavery, ignorance is strength”). Does the inalienable freedom of individual motorized mobility, on which our modern societies are based, have a radiant future outside the imagination and fantasies of the endless technophiles who promise it to us ; just as they promised in the 1960s cities in orbit, flying cars, space stations on the Moon and Mars, underwater farms… And just as they also promised, 70 years ago, and in defiance of the most elementary principle of precaution, overwhelmed by an exalted optimism, to “very soon” find a definitive “solution” to nuclear waste; a solution that we are still waiting for, sweeping the (radioactive) dust under the carpet since then…

Isn’t it curious that we have focused mainly on the problem of the nature of the energy that ultimately allows an engine to function for moving a vehicle and its passengers, ignoring everything else? It’s as if we were trying to make the car as “dematerialized” as digital technology and the new economy it allows. Having succeeded in making the charging stations, the equipment, the satellites and the rockets to put them in orbit, the relay antennas, the thousands of kilometers of cables, and all that this implies of extractivism and industries upstream, disappear as if by magic (and we’re back to Harry Potter again). Yet all very material as is the energy necessary for their manufacture and their functioning, the generated pollution, the artificialization of the lands, etc.⁶⁵

Everlasting promises of flying cars, which would turn humans into new Icarius, arenearly one and a half century old. Future is definitely not anymore what it used to be…

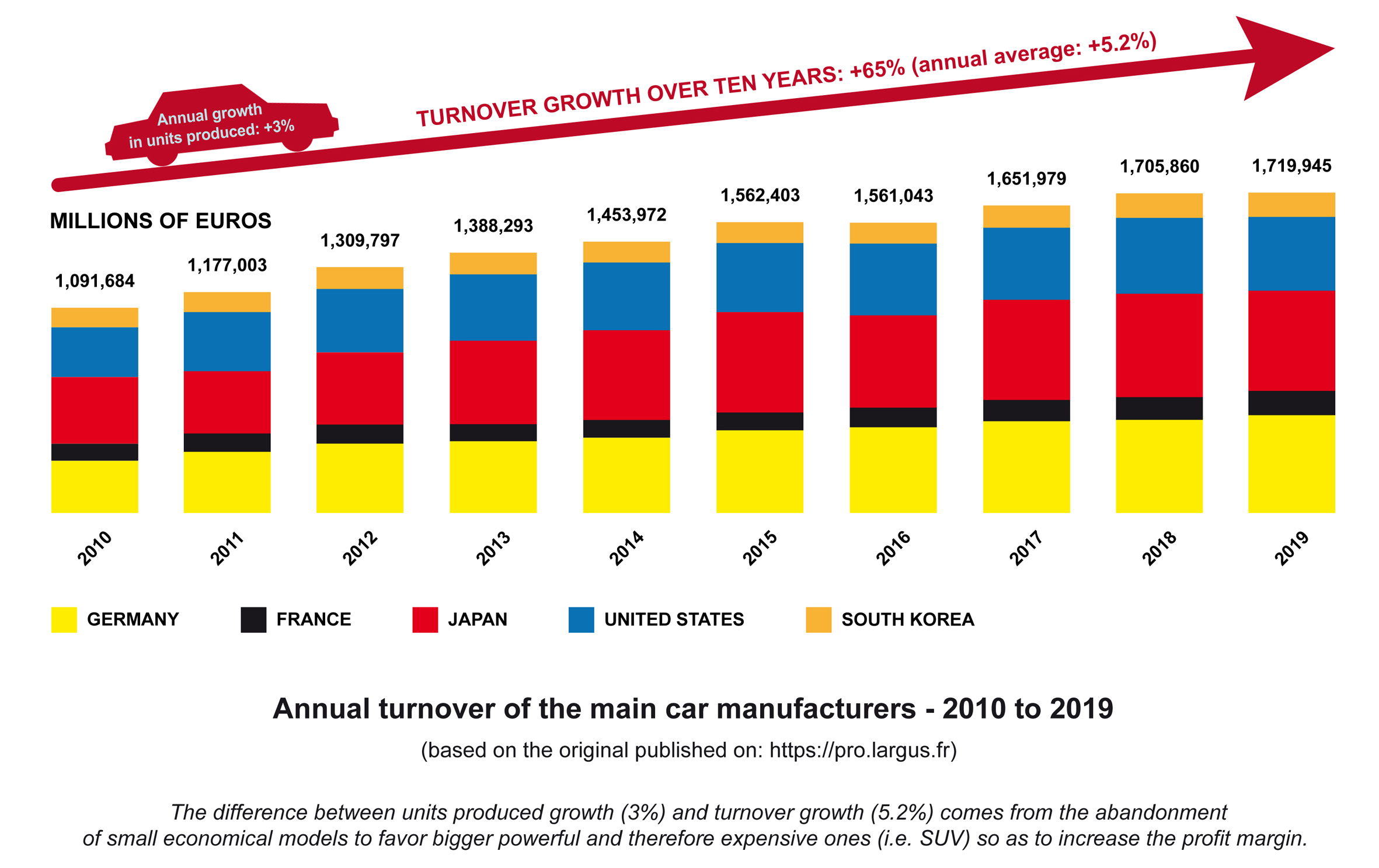

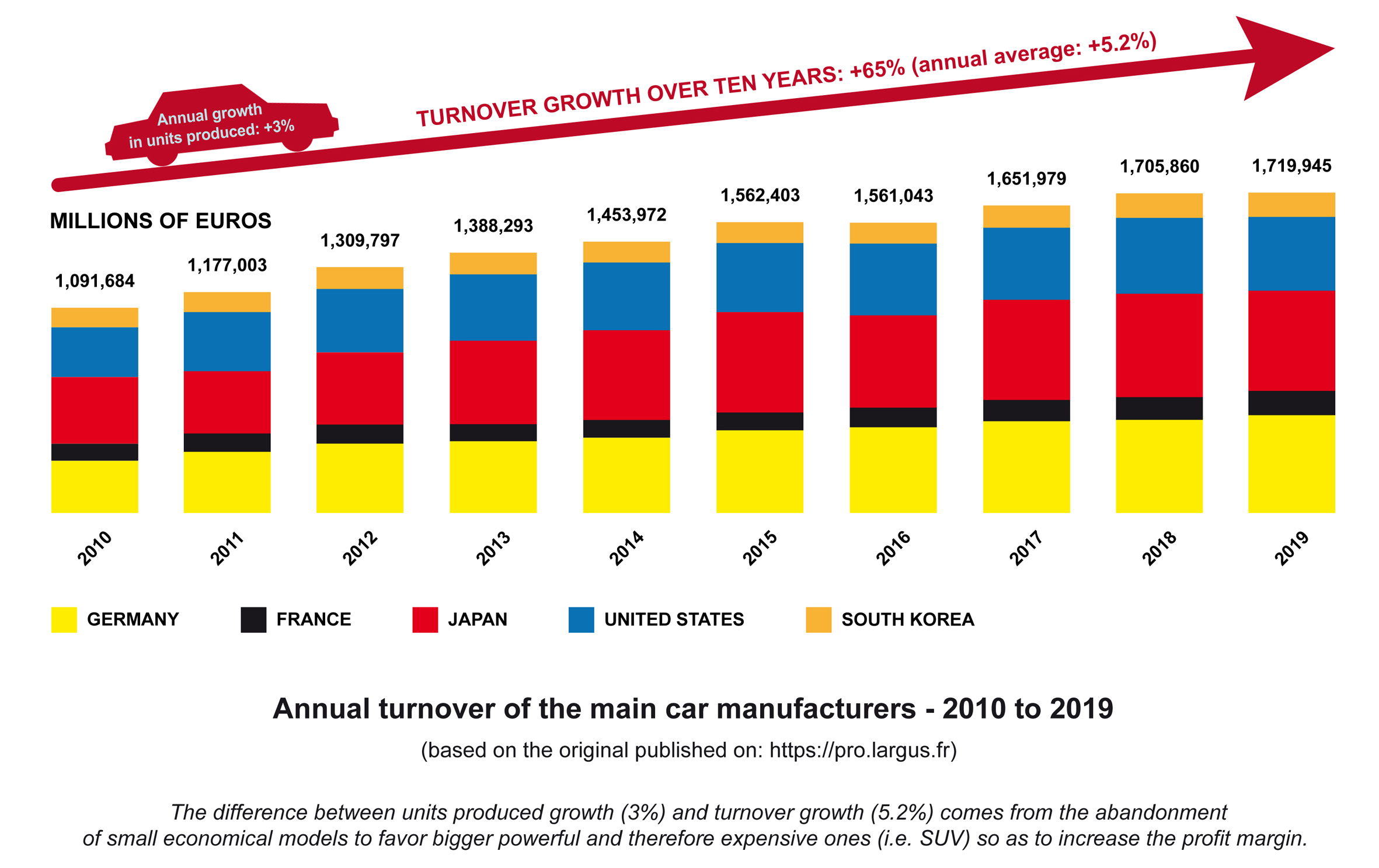

Everyone remains free to continue to take the word of economists who cling like a leech to their sacrosanct infinite growth. To believe politicians whose perception of the future is determined above all by the length of their mandate. Who, in addition to being subject to their hyperactive lobbying, have shares in a world automobile market approaching 1,800 billion Euros per year⁶⁶ (+65% in 10 years, neither politicians nor economists would balk at such growth, which must trigger off climax at the Ministry of the Economy!). That is to say, the 2019 GDP of Italy. Moreover, in 2018 the various taxes on motor vehicles brought in 440 billion Euros for European countries⁶⁷. So it is implicitly out of the question to question, let alone threaten the sustainability of, this industrial sector that guarantees the very stability of the most developed nations.

It is also very difficult to believe journalists who most often, except a few who are specialized, have a very poor command of the subjects they cover. Especially in France, even when they don’t just copy and paste each other. Moreover, they are mostly employed by media financed in large part, via advertising revenues among other things, by car manufacturers who would hardly tolerate criticism or contradiction. No mention of CO2-emitting cement broadcasted on the TF1 channel, owned by the concrete builder Bouygues, which is currently manufacturing the bases for the wind turbines in Fécamp, Normandy. No more than believing startups whose primary vocation is to “make money”, even at the cost of false promises that they know very few people will debunk. Like some solar panels sold to provide more energy than the sun works only for those who ignore another physical fact, the solar constant. Which is simply like making people believe in the biblical multiplication of loaves and fishes.

So, sorry to disappoint you and to hurt your intimate convictions, perhaps even your faith, but the electric car, like Trump’s coal, will never be “clean”. Because as soon as you transform matter from one state to another by means of energy, you dissipate part of this energy in the form of heat. And you inevitably obtain by-products that are not necessarily desired and waste. This is why physicists, scientists and Greta Thunberg kept telling us for years that we should listen to them. The electric car will be at best just “a little less dirty” (in the order of 0 to 25% according to the various studies carried out concerning manufacturing and energy supply of vehicles, and even less if we integrate all the externalities). This is a meager advantage that is probably more socially acceptable but it is quickly swallowed up if not solely in their renewal frequency. The future will tell, at least in the announced increase of the total number of cars, with a 3% per year mean growth in terms of units produced, and of all the infrastructures on which they depend (same growth rate for the construction of new roads). 3% means a doubling of the total number of vehicles and kilometers of roads every 23 years, and this is absolutely not questioned.

Brittany, France, August 2021.

42 With 8 billion tons consumed every year, coal stands in the very first place in terms of carbon dioxide emissions. International Energy Outlook, 2019.

43 https://www.statistiques.developpement-durable.gouv.fr/edition-numerique/chiffres-cles-du-climat/7-repartition-sectorielle-des-emissions-de

44 & https://web.archive.org/web/20211121215259/https://en.reset.org/knowledge/our-digital-carbon-footprint-whats-the-environmental-impact-online-world-12302019

45 https://actu.fr/normandie/le-havre_76351/en-images-au-havre-le-titanesque-chantier-des-fondations-des-eoliennes-en-mer-de-fecamp_40178627.html

46 https://www.connaissancedesenergies.org/fiche-pedagogique/production-de-lhydrogene

47 https://www.iea.org/fuels-and-technologies/oil & https://www.bp.com/content/dam/bp/business-sites/en/global/corporate/pdfs/energy-economics/statistical-review/bp-stats-review-2019-full-report.pdf & https://www.ufip.fr/petrole/chiffres-cles

48 https://jancovici.com/

49 Atually there are 38.2 million cars in France, more than one for two inhabitants:

50 Philippe Bihouix and Benoît de Guillebon, op. cit., p. 32.

51 https://www.lemonde.fr/energies/article/2019/07/22/canicule-edf-doit-mettre-a-l-arret-deux-reacteurs-nucleaires_5492251_1653054.html & https://www.ucsusa.org/resources/energy-water-collision

52 https://www.reuters.com/business/sustainable-business/inconvenient-truth-droughts-shrink-hydropower-pose-risk-global-push-clean-energy-2021-08-13/

53 Co-author with Christophe Bonneuil of L’évènement anthropocène. La Terre, l’histoire et nous, Points, 2016 (The Shock of the Anthropocene: The Earth, History and Us, Verso, 2017).

54 https://www.researchgate.net/publication/242431866_General_Motors_and_the_Demise_of_Streetcars & Matthieu Auzanneau, Or noir. La grande histoire du pétrole, La Découverte, 2015, p.436, and the report written for the American Senate by Bradford C. Snell, Public Prosecutor specialized in anti-trust laws.

55 James Howard Kunstler, The Geography of Nowhere: The Rise and Decline of America’s Man-Made Landscape, Free Press, 1994.

56 Peter D. Norton, Fighting Traffic. The Dawn of the Motor Age in the American City, The MIT Press, 2008.

57 https://www.avenir-suisse.ch/fr/vitesse-puanteur-bruit-et-ennuis/ & Stefan Hollinger, Graubünden und das Auto. Kontroversen um den Automobilverkehr 1900-1925, Kommissionsverlag Desertina, 2008

58 Emmanuel Fureix and François Jarrige, La modernité désenchantée, La Découverte, 2015 & François Jarrige, Technocritiques. Du refus des machines à la contestation des technosciences, La Découverte, 2014.

59 Journée de la filière automobile, Bercy, December 02, 2019.

60 Cours complet d’économie politique pratique, 1828.

61 Richard Bergeron, le Livre noir de l’automobile, Exploration du rapport malsain de l’homme contemporain à l’automobile, Éditions Hypothèse, 1999 & Jean Robin, Le livre noir de l’automobile : Millions de morts et d’handicapés à vie, pollution, déshumanisation, destruction des paysages, etc., Tatamis Editions, 2014.

62 Domenico Losurdo, Contre-histoire du libéralisme, La Découverte, 2013 (Liberalism : A Counter-History, Verso, 2014) & Howard Zinn, A People’s History of the United States, 1492-Present, Longman, 1980 (Une Histoire populaire des Etats-Unis de 1492 a nos jours, Agone, 2003) & Eric Williams, Capitalism & Slavery, The University of North Carolina Press, 1943.

63 George H.W. Bush, Earth Summit, Rio de Janeiro, 1992.

64 https://planet-terre.ens-lyon.fr/ressource/milankovitch-2005.xml

65 Guillaume Pitron, L’enfer numérique. Voyage au bout d’un like, Les Liens qui Libèrent, 2021.

66 https://fr.statista.com/statistiques/504565/constructeurs-automobiles-chiffre-d-affaires-classement-mondial/

67 Source: ACEA Tax Guide 2020, fiscal income from motor vehicles in major European markets.

![Electric Vehicles: Back to the Future? [Part 2/2]](https://dgrnewsservice.org/wp-content/uploads/sites/18/2021/11/Illustration_017.jpg)