by DGR News Service | Dec 19, 2021 | Education, Human Supremacy, Strategy & Analysis, The Problem: Civilization

Non-neutrality of technology & limits to conspiracy theory

By Nicolas Casaux

“For, prior to all such, we have the things themselves for our masters. Now they are many; and it is through these that the men who control the things inevitably become our masters too.”

Epictetus, Discourses, Book IV, Thomas Wentworth Higginson, Ed.

In an essay published in the fall of 1872, entitled “On Authority,” Friedrich Engels, Marx’s alter ego, railed against the “anti-authoritarians” (the anarchists) who imagined they could organize the production of “modern industry” without recourse to any authority:

“Let us take by way of example a cotton spinning mill. The cotton must pass through at least six successive operations before it is reduced to the state of thread, and these operations take place for the most part in different rooms. Furthermore, keeping the machines going requires an engineer to look after the steam engine, mechanics to make the current repairs, and many other labourers whose business it is to transfer the products from one room to another, and so forth. All these workers, men, women and children, are obliged to begin and finish their work at the hours fixed by the authority of the steam, which cares nothing for individual autonomy. The workers must, therefore, first come to an understanding on the hours of work; and these hours, once they are fixed, must be observed by all, without any exception. Thereafter particular questions arise in each room and at every moment concerning the mode of production, distribution of material, etc., which must be settled by decision of a delegate placed at the head of each branch of labour or, if possible, by a majority vote, the will of the single individual will always have to subordinate itself, which means that questions are settled in an authoritarian way.”

He mentioned another example,

“the railway. Here too the co-operation of an infinite number of individuals is absolutely necessary, and this co-operation must be practised during precisely fixed hours so that no accidents may happen. Here, too, the first condition of the job is a dominant will that settles all subordinate questions, whether this will is represented by a single delegate or a committee charged with the execution of the resolutions of the majority of persona interested. In either case there is a very pronounced authority. Moreover, what would happen to the first train dispatched if the authority of the railway employees over the Hon. passengers were abolished?”

What needs to be understood is that:

“The automatic machinery of the big factory is much more despotic than the small capitalists who employ workers ever have been. At least with regard to the hours of work one may write upon the portals of these factories: Lasciate ogni autonomia, voi che entrate! [Leave, ye that enter in, all autonomy behind!]

If man, by dint of his knowledge and inventive genius, has subdued the forces of nature, the latter avenge themselves upon him by subjecting him, in so far as he employs them, to a veritable despotism independent of all social organization. Wanting to abolish authority in large-scale industry is tantamount to wanting to abolish industry itself, to destroy the power loom in order to return to the spinning wheel.”

To put it another way, Engels points out that technical complexity is tied to organizational imperatives. Separate to any individual’s intention, each technology, each technical device, has its own ecological and social implications.

In a similar vein to Engels, George Orwell noted that:

“…one is driven to the conclusion that Anarchism implies a low standard of living. It need not imply a hungry or uncomfortable world, but it rules out the kind of air-conditioned, chromium-plated, gadget-ridden existence which is now considered desirable and enlightened. The processes involved in making, say, an aeroplane are so complex as to be only possible in a planned, centralized society, with all the repressive apparatus that that implies. Unless there is some unpredictable change in human nature, liberty and efficiency must pull in opposite directionsi.”

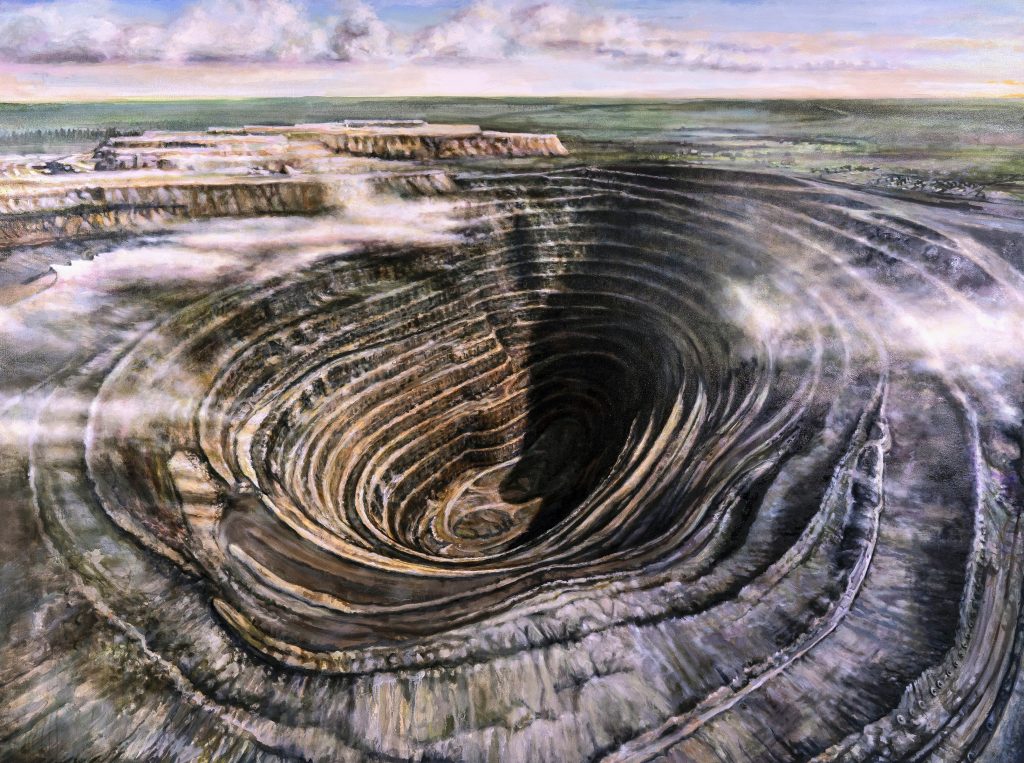

Consider another example. The fabrication of a wicker basket, like that of a nuclear power plant (or a solar photovoltaic power plant, or a smartphone, or a television set), has material (and therefore ecological) as well as social implications. In case of the former, these material implications are related to the collection of wicker. While in case of the second, they relate, among other things, to the procuring (mining, etc.) of the innumerable raw materials needed to build a nuclear power plant, and before that, to the construction of the tools needed to extract those raw materials, and so on – modern technologies are always embedded in a gigantic technological system made up of many different technologies with immense social and material implications.

In his essay entitled “The Archaeology of the Development Idea,” Wolfgang Sachs takes the example of:

“an electric mixer. Whirring and slightly vibrating, it mixes ingredients in next to no time. A wonderful tool! So it seems. But a quick look at cord and wall-socket reveals that what we have before us is rather the domestic terminal of a national, indeed worldwide, system: the electricity arrives via a network of cables and overhead utility lines fed by power stations that depend on water pressures, pipelines or tanker consignments, which in turn require dams, offshore platforms or derricks in distant deserts. The whole chain guarantees an adequate and prompt delivery only if every one of its parts is overseen by armies of engineers, planners and financial experts, who themselves can fall back on administrations, universities, indeed entire industries (and sometimes even the military).”

Back to the wicker basket and the nuclear power plant. The social implications of the wicker basket are minimal. It relies on the transmission of a very simple skill that can be understood and applied by any person. The social implications of the nuclear power plant are immeasurable and far reaching. The construction of a nuclear power plant is based on a social organization capable of generating a massive division and specialization of work, highly qualified engineers, workers, managers of all kinds (i.e. on an organization with a system of schooling, a way of producing an obedient workforce, scientific elites, etc.), of transporting materials between distant points of the globe, etc. (and this was the case in the USSR as well as it is in the USA today).

Therefore, those who claim — often without having seriously thought about the matter — that technologies are “neutral” because one can use a knife to cut butter or slit one’s neighbor’s throat are seriously mistaken. Yes, you can use a knife to cut butter or slit your neighbor’s throat. But no, this certainly does not mean that this technology is “neutral”, it only testifies the existence of a certain versatility in the use of technological tools. They are seriously mistaken because they ignore the conditions under which the knife is obtained, made and produced. They overlook or ignore the way in which the technology they take as an example is manufactured. They assume that the technology already exists — as if technologies fell from the sky or grew naturally in trees, or as if they were simply tools floating in space-time, implying nothing, coming from nothing, just waiting to be used well or badly.

This is, obviously, not the case. No technology is “neutral”. Every technology has social and material requirements. The case of objects like the knife is special in that there exists very simple versions of them, corresponding to low technologies, soft technologies, whose social and material implications are minimal, as well as complex versions of them, which belong to the high-tech realm, whose social and material implications are innumerable. A knife does not have the same social and material implications depending on whether it is a (prehistoric) knife made of flint or obsidian or a knife bought at Ikea made of stainless steel (including chromium, molybdenum and vanadium) with a handle made of polypropylene. The manufacturing processes, the materials needed, the specialized knowledge involved are completely different.

In an essay called “Authoritarian and Democratic Technics”, dated 1964, American sociologist Lewis Mumford distinguished two main categories of technologies (techniques, in his vocabulary). Democratic technologies and authoritarian technologies. Democratic technologies are those that rely on a “small-scale method of production”, that promote “communal self-government, free communication as between equals, unimpeded access to the common store of knowledge, protection against arbitrary external controls, and a sense of individual moral responsibility for behavior that affects the whole community”. They favor “personal autonomy” and give “authority to the whole rather than the part”. Democratic technology has “modest demands” and “great powers of adaptation and recuperation”.

Authoritarian technologies, on the other hand, confer “authority only to those at the apex of the social hierarchy,” rely on the “new configuration of technical invention, scientific observation, and centralized political control that gave rise to the peculiar mode of life we may now identify, without eulogy, as civilization”, on “ruthless physical coercion, forced labor and slavery”, on “complex human machines composed of specialized, standardized, replaceable and interdependent parts — the work army, the military army, the bureaucracy”.

What does this have to do with conspiracy theory? One of the characteristics of a conspiracy theory is the blaming of nefarious individuals for most of the ills that plague the human condition in contemporary industrial civilization. As if all our problems were the result of malevolent intentions of wicked people. Most conspiracists — and this trait is not exclusive to them, it also characterizes most people on the left — imagine that without these bad people and their bad intentions, we could live in a just and good, egalitarian and sustainable technological civilization. It would simply be a matter of electing good rulers or reforming society in multifarious ways (as if systems and objects of themselves had no requirements, no implications).

However, as we have made clear, we should recognize that all things — including technologies — have requirements and implications independent of the will of any specific human being.

As Langdon Winner noticed in his book The Whale and The Reactor, each and every technology requires its environment

“to be structured in a particular way in much the same sense that an automobile requires wheels in order to move. The thing could not exist as an effective operating entity unless certain social as well as material conditions were met.”

This is why some technologies (certain types of technologies) are, by necessity, linked to authoritarianism. This is most notably the case, to state the obvious, of all “high technologies”, of all modern technologies in general. We should note that, historically, the more civilization became global (the more the economic system became global), the more powerful its technologies became, the more rigid and authoritarian. This process is still ongoing. And the more powerful and dangerous technologies become, like nuclear power or artificial intelligence, the more authoritarianism — a thorough control of people and processes and everyday life — becomes necessary in order to prevent any catastrophe, in other words, the more technocratic society becomes.

Let us take another thing as an example: the size of human societies. In his “Project of Constitution for Corsica”, written in 1765, Jean-Jacques Rousseau noted:

“A purely democratic government is more suitable for a small town than for a nation. One cannot assemble the whole people of a country like that of a city, and when the supreme authority is entrusted to deputies the government changes and becomes aristocratic.”

In his book The Myth of The Machine (1967), Lewis Mumford similarly noted:

“Democracy, in the sense I here use the term, is necessarily most active in small communities and groups, whose members meet face to face, interact freely as equals, and are known to each other as persons: it is in every respect the precise opposite of the anonymous, de-personalized, mainly invisible forms of mass association, mass communication, mass organization. But as soon as large numbers are involved, democracy must either succumb to external control and centralized direction, or embark on the difficult task of delegating authority to a cooperative organization.”

The size of a human society has, quite logically, implications, meaning that it determines — at least in part — how its members are able to organize themselves politically, independent of human preferences. One can wish with all one’s heart to establish a real democracy (i.e. a direct democracy) with 300 million people, but in practice it is (very) complicated.

All things have their requirements.

We could take another example, related to the previous one: Human density. Since its advent, civilization has been synonymous with the emergence of infectious diseases, epidemics and pandemics (the Athens plague, the Antonine plague, etc.), because one of its intrinsic characteristics is a high concentration of domesticated animals, where pathogens can mutate and reproduce, near a high concentration of — also domesticated — human beings (assembled in cities), who can thus be contaminated by the pathogens of their domesticated animals, and then infect each other all the more quickly and extensively as the available means of transportation are rapid and global. In addition to all this, because of its needs, every civilization has a systemic imperative to degrade existing ecosystems, to disturb nature’s dynamic equilibriums, which increases the risk of new epidemics or pandemics.

In order to alleviate these problems, industrial civilization has developed various remedies, including vaccination.

Just as industrially raised pigs would probably not survive in their environment without medication (antibiotics and others), urban existence and civilized life (the life of industrially raised human beings) would be difficult without vaccines [or some other form of palliative], with even more numerous and devastating epidemics and pandemics.

Here we see again that things have their requirements. The list of possible examples goes on and on. This means, among other things, that life in cities, with running water, electricity and high technology in general has many social and material implications, among which, in all probability, a hierarchical, authoritarian and unequal social system. (It is certainly the case that the requirements of things are not always extremely precise, offering relative latitude: the sanitary pass in France was probably not an absolute necessity, since many countries didn’t implement it, at least not yet; on the other hand, all of the nation-states worldwide are constituted in a similar way since one finds police forces, a president etc. everywhere).

Yes, some individuals already own and seek to monopolize more and more power and wealth. But if we live in authoritarian societies today, it is certainly not — not onlyii — because of greedy individuals, lusting for control, power and wealth. The authoritarian and unequal character of industrial civilization is not — not only — the result of the intentions and deeds of a few ultra-rich people like Klaus Schwab or Bill Gates. It is, in great part, the result of the requirements of the things that constitute it — technical systems, specific technologies, economic systems, etc.

If we want to get rid of authoritarianism, inequality, and found true democracies, we have to give up all those things whose requirements prevent us from doing so — in particular, we have to give up modern technologies.

ii� This is in its review of A Coat of Many Colours: Occasional Essays by Herbert Read, in the Collected essays, journalism and letters of George Orwell, Volume IV, In Front of Your Nose, 1945-1950.

ii� “Not only” because initially, if we came to live in authoritarian societies, in industrial civilization, it is largely because of the intentions of a few groups of individuals, who gradually (and by means of force, violence) imposed this new socio-technical organization on the populations. And because the rich and powerful, the elite, sometimes conspire (history is full of examples of conspiracies that are now officially acknowledged) to make people accept new technical systems, which come with certain requirements. Once these systems have been accepted and adopted by people, they have no other choice, if they wish to keep them, than to comply with their requirements.

by DGR News Service | Dec 9, 2021 | Climate Change, Direct Action, Human Supremacy, Indirect Action, Obstruction & Occupation, Protests & Symbolic Acts, The Problem: Civilization, The Solution: Resistance

Editor’s note: The preferred method to stop a coal port for hours or days would be anonymously, so as to “live to fight another day”. But this action does highlight the fact that this port exports 158 million tonnes of coal a year. This action shows just how vulnerable the system is. It can be stopped when two people have the courage to throw their bodies on the cogs.

We must fight empire “by any means necessary.”” —Frantz Fanon

This story first appeared in Common Dreams.

“It is now our duty to defend the biosphere that gives us life and to every person that Australia has forgotten and ignored,” said Hanna Doole of the campaign group Blockade Australia.

By JULIA CONLEY

November 17, 2021

A two-person protest halted operations at the world’s largest coal port early Wednesday morning, as two women scaled the Port of Newcastle in New South Wales, Australia to protest their government’s refusal to take far-reaching climate action.

Hannah Doole and Zianna Faud—both members of the campaign group Blockade Australia—filmed themselves suspended on ropes attached to the port, where they forced the transport of coal to stop for several hours.

“I’m here with my friend Zianna, and we’re stopping this coal terminal from loading all coal into ships and stopping all coal trains,” said Doole.

The Port of Newcastle exported 158 million tonnes of coal in 2020, and its production is not expected to slow down in the coming years despite clear warnings from climate scientists that the continued extraction of coal and fossil fuels will make it impossible to limit global heating to 1.5°C above preindustrial temperatures.

“Another system is possible and we know that because one existed on this continent for tens of thousands of years,” said Doole. “It is now our duty to defend the biosphere that gives us life and to every person that Australia has forgotten and ignored.”

“In a system that only cares about money, non-violent blockading tactics that cause material disruption are the most effective and accessible means of wielding real power.”

On the heels of COP26, where world leaders agreed to a deal pledging to phase down “unabated” coal power, Australian Prime Minister Scott Morrison said Monday that the country will continue producing coal for “decades to come.”

Despite the state of emergency New South Wales officials were forced to declare less than two years ago as wildfires scorched millions of acres of land, destroyed more than a thousand homes, and killed nearly 500 million animals and more than a dozen people, Morrison claimed his continued commitment to coal extraction was akin to “standing up for our national interests.”

Morrison pledged last month to make Australia carbon-neutral by 2050, but his statement was denounced as a “political scam, relying on unproven carbon capture technology without phasing out fossil fuel extraction.

Organizers said Doole and Faud’s protest took place on Blockade Australia’s tenth straight day of direct actions targeting the Port of Newcastle as the grouo denounces the government’s plan to continue exporting the second-largest amount of coal in the world per year.

Earlier this week a woman prevented coal trains from entering the Port of Newcastle by locking herself to a railroad track, and on Tuesday two other advocates held a demonstration on machinery used to load coal at the port.

“In a system that only cares about money, non-violent blockading tactics that cause material disruption are the most effective and accessible means of wielding real power,” said Blockade Australia on Wednesday.

The two demonstrators were arrested after scaling the port for several hours. Faud appeared in court on Wednesday following the protest, where she pleaded guilty to charges of “hindering the working of mining equipment,” according to The Washington Post. She was ordered to pay a $1,090 fine, sentenced to community service, and ordered not to associate with Doole for two years. Doole is expected to appear in court on Thursday.

Blockade Australia is preparing to hold a large demonstration next June in Sydney, where the group plans to “participate in mass, disruptive action” in Australia’s political and economic center.

Banner image: flickr (CC BY-NC-SA 2.0)

by DGR News Service | Dec 5, 2021 | Direct Action, Human Supremacy, Mining & Drilling, Property & Material Destruction, Repression at Home, The Problem: Civilization, The Solution: Resistance

Sentenced to eight years in prison for acts of sabotage, water protector Jessica Reznicek reflects on her faith-driven resistance.

By Cristina Yurena Zerr

This article was first published in the German newspaper taz, and has been translated and edited for Waging Nonviolence.

On June 28, the federal court in Des Moines, Iowa was silent and filled to capacity. Fifty people were there to witness the sentencing of 40-year old Jessica Reznicek, charged with “conspiracy to damage an energy production facility” and “malicious use of fire.” The prosecution, asking for an extended sentence, argued that Reznicek’s acts could be classified as domestic terrorism.

This was not the first time Reznicek had been on trial, but this time she was facing a prison sentence of up to 20 years.

Sitting across from her was U.S. District Court Judge Rebecca Goodgame Ebinger, the prosecutor and an FBI agent. Numerous police officers in bulletproof vests stood around the courtroom. The defendant was called upon to give her closing speech.

In her loud, clear voice, Reznicek told them about her strong connection to the water. In her childhood she regularly went to the river to swim and play. But that’s no longer possible, she said, because the two rivers that run through Des Moines — Iowa’s capital — are now poisoned by agrobusiness pesticides and waste.

It was for these very personal reasons that she decided to fight the construction of the Dakota Access Pipeline, Reznicek told those in attendance. At least eight leaks, she explained, had already occurred in 2017, with 20,983 gallons of crude oil leeching into soils and the waterways. “I was acting out of desperation,” she said, describing her motivations for sabotage.

“Indigenous tradition teaches us that water is life. Scripture teaches that in the beginning, God created the waters and the earth and that it was good.” With these words, she ended her closing argument. The prison sentence followed shortly thereafter: eight years in federal prison, three years of probation, and a restitution of $3,198,512.70 to the corporation Energy Transfer.

The Des Moines River (Cristina Yurena Zerr)

On July 24, 2017 — two years before sentencing — Jessica Reznicek can be seen in a shaky video with her activist partner Ruby Montoya, a former elementary school teacher who was 27 at the time. They stand in front of a group of journalists next to a busy street. The speech they give would drastically change their lives.

After several months of secretly sabotaging one of the country’s most controversial construction projects, the two women, whose paths would later part, went public. “We acted for our children because the world they inherit does not meet their needs. There are over five major bodies of water here in Iowa, and none of them are clean. After having explored and exhausted all avenues of process, including attending public hearings, gathering signatures for valid requests for environmental impact statements, participating in civil disobedience, hunger strikes, marches and rallies, boycotts and encampments, we saw the clear refusal of our government to hear the people’s demands.”

That’s why Reznicek and Montoya burned five machines at a pipeline construction site in Iowa on election night in November 2016. They would later change their methods, using a welding torch to dismantle the pipeline’s surface-mounted steel valves, delaying construction by weeks. “After the success of this peaceful action, we began to use this tactic up and down the pipeline, throughout Iowa,” the two women say.

But no media reported on their activities; the corporation cited other — false — reasons for the delay. When the activists noticed during an action that oil was already flowing in the pipes, they decided to go public, as they had to admit a kind of defeat.

The two women appear clear and determined on this day in the summer of 2017 as they take turns reciting their pre-written text. “If there are any regrets, it is that we did not act enough.” They end their speeches and are led away in handcuffs by three police officers.

Using the slogan “Mni wiconi,” meaning “Water is Life,” in the Lakota (Sioux) language, a broad movement was organized in 2016 against the construction of the Dakota Access Pipeline. The protest of the Standing Rock Sioux tribe garnered national and international attention.

The tribe sees the construction of the pipeline as a threat to their water supply because the pipeline runs under Lake Oahe, which is near the reservation. Other bodies of water are also at risk because the pipeline crosses under rivers and lakes in many places, which could contaminate the drinking water of many people in the event of an accident. In addition, ancient burial sites and sacred places of great cultural value would be threatened by the construction. Opponents of the pipeline speak of ecological racism — not only because Indigenous rights to self-government would be curtailed, but also because the construction of so-called Man Camps (temporary container cities for construction workers who move from other states) would lead to prostitution and an increase in violence against Indigenous women.

Their government — the Sioux Tribe is a sovereign nation — issued a resolution back in 2015 saying the pipeline “poses a serious risk to the very survival of our tribe and […] would destroy valuable cultural resources.” Construction would also break the Fort Laramie Treaty, which guarantees them the “undisturbed use and occupation” of reservation land. But their arguments went unheard by both the company and the government.

The operating company said the pipeline would not harm the environment, would not affect Indigenous rights and would not pose a threat to drinking water supplies. But the protest, which stretches across several states along the pipeline, has developed into one of the largest environmental movements in the United States. Native Americans from different nations and reservations are joining, along with landowners, environmental organizations and left-wing autonomous movements.

Reznicek first heard about the pipeline when she was released from prison six years ago, after serving a two-month stint for her protest against a U.S. military weapons contractor in Omaha, Nebraska. An organizer from Standing Rock had come to Des Moines to mobilize people for the protest. “I decided that I wanted to learn more about Indigenous ceremony, understanding that I am a white person, I cannot just go in and express my demands. And I also wanted to focus on stopping the Dakota Access Pipeline Project. So I drove up to Standing Rock.”

Where it all began

On a road on the outskirts of Des Moines — a city home to numerous insurance companies — large trees tower above the wooden row houses, providing shade on a hot July day.

Above the porch of one of the houses hangs a small sign that reads “Catholic Worker House.” In front of the back part of the building are tables and benches with people sitting on them. Music is playing, people are singing, someone is asleep on a bench.

In the kitchen of the house, Jessica Reznicek stands in front of the stove and slices five chicken breasts, freeing the meat from the bones. Next to them is a large pot of mashed potatoes, into which she generously spreads butter. “Our guests love butter,” Reznicek laughs. The kitchen looks as if many meals have been cooked there. Posters with anti-war messages and protest slogans are hung around the small room. On the windowsill in front of Reznicek is a statue of a bishop with a rosary around his neck.

Twice a week, Jessica Reznicek cooks for the homeless guests who come here. Usually they eat together in the living room, but since the outbreak of the coronavirus pandemic, the food is distributed through the window.

“I like the days when I’m in charge of the kitchen. It takes my mind off all the things that are going on in my head,” Reznicek says as she begins washing a mountain of dishes.

Two years have passed since her protests were made public. A year ago, Jessica Reznicek moved back into the community, spending time there on house arrest. Here, where it all began, her long journey ends. She has one week left before needing to report to prison.

Just before the food is served, the kitchen and living room fill up. Two of Reznicek’s friends are there, residents of the house and volunteers from outside — together they begin to serve food to the guests.

Reznicek has been in and out of the house for 10 years. Most people know her story: “The one who blew up the pipeline?” asks Jimmy — one of the homeless guests — laughing as he tastes the still-warm mashed potatoes. The fact that she will soon be gone saddens many of the residents. For the majority of them, prison is a familiar place. But no one here has been incarcerated as long as Jessica Reznicek will be.

The Dingman House, named after a late bishop in Des Moines, is one of four side-by-side buildings of the Catholic Worker community. Christianity and anarchism meet here. In these self-organized “houses of hospitality,” which function independently of the church, people live and work among the poor in the spirit of the Sermon on the Mount. The Christian message of social justice and solidarity with the marginalized becomes everyday practice. There is not much overlap with the institutional Catholic Church. In the bathroom, where homeless guests can shower, there are free condoms; trans people find shelter here and women sometimes lead church services.

Preparations for prison

The Berrigan House across the street — named after two priests who became known for their actions of civil disobedience against the Vietnam War — has always been a place of resistance, where protest actions are planned and activists find shelter. This is where Reznicek prepared her actions against the pipeline.

As in the house next door, the walls are covered with posters calling for resistance against war, racism and injustice. It is a colorful, chaotic and untidy atmosphere. Reznicek and her friends Alex and Monty sit at the table in the living room. The two are among her closest supporters. They just had a video conversation with Reznicek’s lawyer to discuss the final steps before she goes to jail.

A month after Reznicek is sentenced to eight years in prison, they launched a campaign called “Water Defenders Are Never Terrorists.” Within a few weeks, they were able to collect thousands of signatures. Their goal: a petition to President Joe Biden and Congress demanding the terrorism charges be dropped.

The list of things to do before Reznicek goes to prison is long: return the electronic ankle bracelet, pick up the copy of her high school transcript she needs so she won’t have to attend classes in jail. T-shirts demanding her release are to be printed. Reznicek also wants to develop photos that Alex will later send to her in prison so she can decorate her cell with them. But they also want to see her favorite musical Rent, go dancing one more time, invite friends and celebrate. There is a lot of laughter when the three get together.

Jessica Reznicek’s supporters Monty and Alex in the Christian Berrigan House. (Cristina Yurena Zerr)

After the meeting, Jessica Reznicek packs a vacuum cleaner and cleaning supplies and heads out. With permission from her probation officer, she started cleaning private homes a year ago. She also worked at a pizzeria from time to time.

Why is Jessica Reznicek willing to spend eight years of her life in prison because of her commitment to clean water? She was studying political science in Des Moines and married when she learned about the Occupy Wall Street movement in 2011. Shortly after, she decided to go to New York for the protests. This meant the end of her marriage. From the East Coast, she began a new life of sorts, always on the move, searching for a way to make her contribution to a more just world.

Reznicek traveled twice to Palestine and Israel, where she was deported for protesting in solidarity with the Palestinian people. She visited the Zapatistas in Mexico and spent time in Central America with the Indigenous people of Guatemala. In South Korea, she protested the construction of a U.S. Navy base. “So I feel like all of these experiences culminated at this point in my life when I heard about the Dakota Access Pipeline.”

The Catholic Worker community in Des Moines was central to her politicization. She stumbled upon the organization after returning to Iowa from New York. There begins what she later calls a conversion: a return to the Christian faith and her Catholic roots. At the same time, this means a radicalization in the struggle against injustice: Jesus Christ is seen Catholic Workers as a revolutionary who stood up for the disenfranchised, for the weak and the poor. He wanted to drive the kings from their thrones and bring justice. And he died on the cross without resisting his judgement.

Three months after Jessica Reznicek made her actions public in 2017, the Berrigan home was surrounded by the FBI. “It was like 4:30 in the morning when they were pounding on the door. The house was actually shaking. I ran downstairs and could see around 50 agents through the window with big guns and vests.”

When she opened the door, the house was stormed by about 50 uniforms. She was thrown to the ground and held at gunpoint, she said.

She then spent a year in hiding, calling it her wanderings. “I wasn’t necessarily underground. I think that I was running and I was hiding, but it was not exclusively from the federal government. I was not hiding from prison. I was hiding from everything.”

When she broke down after 10 months in Colorado, she finally realized she needed help. It won’t come from people or places, Reznicek says, but from her relationship with God. After this experience, she realized she wanted to live in a place where she could encounter God, so she decided to enter a Benedictine convent as a novice. But no sooner does she arrive than Reznicek is again picked up by the FBI and charged. They send her back to Des Moines — to the Berrigan home — to await the verdict under house arrest.

For the last four days before she goes to prison, Jessica Reznicek was given permission to visit the sisters at the convent community in Duluth. After her incarceration, she would like to move there or — if that’s not possible — live as close to the convent as she can.

On August 11th, Benedictine sisters drove Jessica Reznicek to the women’s prison in Wascea, Minnesota, four hours away. There, 714 women currently live behind the walls and fences.

Three hundred miles to the north is the town of Bemidji, home of Energy Transfer, the energy company to which Reznicek will be in debt for the rest of her life. A new pipeline called Line 3 has been under construction at this location for several years. As with the Dakota Access Pipeline, the region’s Indigenous inhabitants — the Anishinaabe and Ojibwe tribes — will be most affected by the project.

“Today I feel sad to be saying my final goodbyes to loved ones,” Reznicek said. “I am strengthened, however, knowing that I’m still standing with integrity during this very important moment in history, as there truly is no other place to be standing at a time like this.”

With these words she takes leave of her friends and turns to face the prison gates.