by DGR News Service | May 9, 2021 | Biodiversity & Habitat Destruction, Colonialism & Conquest, Education, Mining & Drilling, Strategy & Analysis, Toxification

By Straquez

The Colonial Years

Of course, Mexico has been in the front line of atrocities and destruction that come out of mining. Mexico is a land blessed with wide biodiversity that includes minerals that have caught the attention of foreign companies who then act as the machinery to do what this industrial culture does best –converting the living into the dead. High revenue for the company stakeholders, negative benefit for the inhabitants and nothing but endless destruction for the land.

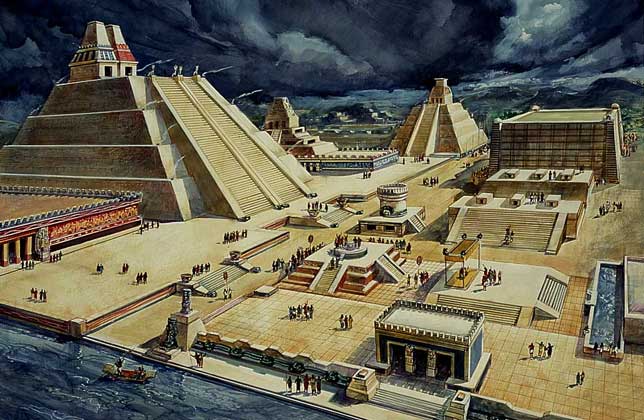

It is said that Aztecs used to embellish and protect their bodies with jewelry, such as necklaces with charms and pedants, armlets, bracelets, leg bracelets, and rings. They would also use tools and vases fabricated with precious metals like gold and silver. These metals were found in deposits located on the surface and not underground like nowadays, this allowed the usage of such mineral resources without much effort or effect.

In 1521, Tenochtitlan, the Aztec capital, was taken over by the Spanish army consolidating Mexico’s Conquest. From then on, mining as an industry started in Mexico as Spaniards started to exploit places where mineral deposits could be located. Mining was carried out mostly in the North and Center of what is now modern day Mexico. Many important mineral deposits started to be discovered in places that later would become famous as they would generate wealth (for whom?) and human settlements. It was only a matter of time before the land subject to mining would be turned into cities such as Guanajuato, San Luis Potosi, Zacatecas, Taxco, Chihuahua and Durango.

Mines kept spreading and mining created many jobs and wealth (I hate to be repetitive, but whose wealth?). Is there even a mention of all the evils done to the indigenous land and people? Not at all, the history of mining is portrayed as progress, as an unquestionable good thing, as a victory and in no terms as a defeat or loss. The whole History of Civilization is pretty much like that, now that I think of it.

After Independence

When the Independence movement of Mexico started in 1810, mining projects were negatively affected and had to be stopped. It was not until 1823 when the movement ended that mining activity was restarted. Remember that I mentioned my surname Straffon being from Cornwall, England? Well, it was precisely during these years that the British Real del Monte Company was established thanks to English capital. This company provided both technology and workforce, some of it straight from Cornwall to re-establish silver mines located in Real del Monte, Hidalgo. 1,500 tons of equipment including 9 steam engines with their large boilers, 5 for pumping, 2 for crushing ore and 2 for use in powering saw mills; various pumps; large cast iron pipes to connect the pumps to be placed at the bottom of the mines with the surface. And so started the rebuilding and modernization of the district’s mining industry. The Cornish miners had brought the Industrial Revolution to Mexico.

By the beginning of the 20th century, Mexico was entering a major political transformation as new laws and codes were created. During Porfirio Diaz’ administration, for example, most of the railroad infrastructure was built all through the country, focusing on the main mining centers that were already established. Then the American corporations showed up offering the means for better extraction as mines during the times of Nueva España were certainly used, but could not be exploited to their maximum because Spain lacked the technology and resources to do so.

The Fresnillo Company, Mazapil Cooper Co., Peñoles Mining Co., and Pittsburg & Mexico Tin Mining Co. were some of the companies looking to make a profit out of Mexico’s mines. Parallel industries started to rise, the economy diversified and the country’s elite dreamed of Mexico being on its way to becoming a world economy. Metallurgical processes were improved with maximum return on capital and mineral processing efficiency as the main goal. The bonanza would cease somewhat in the 1960s when the mining industry was nationalized and mine administration passed to the charge of Mexican professionals.

Then came NAFTA, and in 1992 mining laws were modified substantially in order to accommodate the demands of big national and transnational corporations. Compared to the prior 300 years, production of gold and silver doubled even though several communities resisted the exploitation. Social and environmental damage increased substantially as a consequence due to legal impunity and the ability of the mining organizations to trample over human rights. The Mexican Mining Law of 1992 is a unique and unconstitutional piece of legislation, and rides roughshod over earlier laws which allowed for judicial challenges and which consequently made it difficult for companies to carry on their business with impunity. The solution of the mining organizations was, of course, to create a whole web of corruption that extends to the three branches of government. We are still living the influence of NAFTA until this very day. Business as usual.

Keep on Digging

Doctor María Teresa Sánchez Salazar has set out very interesting mine “conflict maps” which consider many parameters including land conflict, environmental conflict, social conflict, labor conflict or a combination of those factors. Data shows that 75% of these conflicts have to do with land, that is, land grabs by the mining companies or due to environmental conflicts, and almost 70% of them happen in open-pit mines. Another interesting number – 60% of the conflicts have involved foreign company owned mines.

She adds that there are places where conflict started due to land grab and the subsequent leasing to mining companies and the implementation of ways to displace people from their native lands. Of a total of 181 natural areas, 57 have been leased for mining. Eight of them focus more than 75% of the surface to this activity. Twenty of them have at least 93% of their surface leased. One example is the Rayón National Park in Michoacan, its land is practically 100% leased for mining as well as Huautla Mountain Range that is between Morelos, Puebla and Guerrero.

Safety is also an issue for the Mexican mining sector. There are powerful cartels that have quite an influence in the entire country, including mining states such as Sonora, Chihuahua, Sinaloa and Guerrero. Mines have been object of many armed robberies that have increased during the COVID-19 pandemic. Extortion, threats and employee kidnapping have been the most common crimes reported by the mining companies.

If this was a Robin Hood kind of deal then I should certainly support it, but in the end workers are the most affected, operations are seldom slowed down and the exploitation just does not stop. If the criminal gangs were to take over, not much would change as, let’s be honest, both companies and cartels pretty much operate the same way but at a different scale.

Bacadéhuachi

In times prior to the year 1600, this area was inhabited by Opata indigenous settlements. In the year 1645 a mission named San Luis Gonzága de Bacadéhuachi was founded by the Jesuit missionary Cristóbal García. Its current inhabitants dedicate their lives to taking care of livestock and making cheese, bread and tortillas which are sold among themselves; within the world economy, they don’t have much of a choice. Being only 270 kilometers away from Hermosillo, capital of the State of Sonora, the road takes 5 hours to transit due to the uneven and complex terrain that in turn makes it a dangerous travel.

This town is on the same route of the high mountain range that takes you to Chihuahua, its neighbor state. This is a high-risk road as armed conflicts are constantly raging between groups that are looking to take control of this area. Some months ago, armed men went into the municipality creating such a situation and ending the peaceful environment to the point that the Mexican National Guard and the State Police now have to be constantly present.

Bacadehuachi has around 500 houses, most of them made of adobe, occupied by around 1,083 people according to the The National Institute of Statistics and Geography (INEGI). It has cobblestone roads and few are made of concrete due to the minimal vehicle transit. It is more common to see people on horses or donkeys than in motor vehicles. Everything is around the corner, there are no gas stations nearby. It has 3 municipal police officers that issue around 10 different fines a year. There is only one health center for basic checkups and a doctor is available every 3 days.

Regarding education, only one preschool, one primary school and one secondary school exist. For those who want to receive higher education, their only choice is to go to Granados, a municipality 50 kilometers away from the town. The road is risky to say the least, young students must stay at the neighboring town and go back to their families at the weekends in a municipality sponsored bus. To go to college is a victory, a luxury, a rare occurrence for the townspeople.

Don’t Know What I’m Selling

Miguel Teran is a farmer and former owner of La Ventana ranch. He sold his land to Bacanora Lithium for the Sonora Lithium Project. He asserts that the first explorations started back in 1994. Geologists came to the La Ventana ranch in government cars. They took some soil samples, came back 8 years later, measured the land and after that they never came back. Ten years ago, Bacanora Lithium carried out some studies. They drilled around 115 holes with the permission of Miguel and then they offered to buy the land.

I told them: you know what you’re buying, but I don’t know what I’m selling. Don’t take advantage of me. That’s how the negotiation started, but they wanted to pay as if it was a mere piece of land.”

Miguel wasn’t disappointed yet he acknowledges that he could have made a better deal as he has since found out what treasure lies in the 1,900 hectares that were sold and integrated into the Sonora Lithium Project. For the time being and until the mineral is extracted, Miguel may allow his cows to graze there as stipulated in the contract.

I am within my rights until I get in the way, but I have already bought some land.” Finally, he adds, “sometimes my car battery would fail and they would tell me that I had lithium here, but I only know about horses and chickens; not lithium.”

The Trauma of Our Technological Selves

As a city-dweller, my experience with Nature has been for the most part parks and decorative gardens. Since I live so disconnected from the land itself, I can only enter into relationship with my own species, our creations and the animals we call pets. For a long time I’ve been scared of insects and even though working in a garden has helped diminish the feeling, I still feel uncomfortable in certain scenarios. Soil and its minerals are even weirder to me, because I had never considered them something other than a resource, a component that can be used for my benefit through technology. They don’t seem alive, they don’t seem to have any other purpose than sitting there for us to transform them into something else.

Perhaps my biggest realization during my journey to connect with the land is the enormous damage that Capitalism, Colonialism and Industrialism have inflicted on the planet. It has reached the point that we are also physically, psychologically, emotionally and spiritually bent and broken enough for us to barely notice the indifference and violence around us. Indifference and violence done to each other and to ourselves. And yet, those who notice don’t always take action. Even less, those who know and take action don’t have a clear idea, much less a strategy to stop the abuse.

This is not something that modern technology can fix. Not the electric cars, not the solar cells nor the electric batteries. Not the tote bags and the bamboo toothbrushes that you can use as compost. Our home is being gutted and we just stand there watching, unsure on what to do. When you actually want to stop a killer, you go ahead and do it. You don’t offer knives from recycled metal or whips made out of hemp. You go ahead and put an end to the abuse by neutralizing any capacity to inflict damage that the perpetrator might have. You stop the killing, you stop the behavior, you commit yourself to do so.

Today I read that only 3% of world’s ecosystems remain intact. Civilization is going down regardless of what we do. Nothing can grow indefinitely without collapsing. The real question is what will be left when our civilization goes down. Our struggle resides in stopping it before there is nothing left.

Cristopher Straffon Marquez a.k.a. Straquez is a theater actor and language teacher currently residing in Tijuana, Baja California, Mexico. Artist by chance and educator by conviction, Straquez was part of the Zeitgeist Movement and Occupy Tijuana Movement growing disappointed by good intentions misled through dubious actions. He then focused on his art and craft as well as briefly participating with The Living Theatre until he stumbled upon Derrick Jensen’s Endgame and consequently with the Deep Green Resistance: Strategy to Save the Planet both changing his mind, heart and soul. Since then, reconnecting with the land, decolonizing the mind and fighting for a living planet have become his goals.

by DGR News Service | May 8, 2021 | Biodiversity & Habitat Destruction, Colonialism & Conquest, Education, Mining & Drilling, Strategy & Analysis, Toxification

By Straquez

Mine is the Ignorance of the Many

I was born in Mexico City surrounded by big buildings, a lot of cars and one of the most contaminated environments in the world. When I was 9 years old my family moved to Tijuana in North West Mexico and from this vantage point, on the wrong side of the most famous border town in the world, I became acquainted with American culture. I grew up under the American way of life, meaning in a third-world city ridden with poverty, corruption, drug trafficking, prostitution, industry and an immense hate for foreigners from the South.

Through my school years, I probably heard a couple of times how minerals are acquired and how mining has brought “prosperity” and “progress” to humanity. I mean, even my family name comes from Cornwall, known for its mining sites. The first Straffon to arrive from England to Mexico did so around 1826 in Real del Monte in the State of Hidalgo (another mining town!). However, it is only recently, since I have started following the wonderful work being done in Thacker Pass by Max Wilbert and Will Falk that the horrors of mining came into focus and perspective.

What is mining? You smash a hole in the ground, go down the hole and smash some more then collect the rocks that have been exposed and process them to make jewelry, medicines or technology. Sounds harmless enough. It’s underground and provides work and stuff we need, right? What ill could come out of it? After doing some digging (excuse the pun), I feel ashamed of my terrible ignorance. Mine is the ignorance of the many. This ignorance is more easily perpetuated in a city where all the vile actions are done just so we can have our precious electronics, vehicles and luxuries.

Mine Inc.

Mining, simply put, is the extraction of minerals, metals or other geological materials from earth including the oceans. Mining is required to obtain any material that cannot be grown or artificially created in a laboratory or factory through agricultural processes. These materials are usually found in deposits of ore, lode, vein, seam, reef or placer mining which is usually done in river beds or on beaches with the goal of separating precious metals out of the sand. Ores extracted through mining include metals, coal, oil shale, gemstones, calcareous stone, chalk, rock salt, potash, gravel, and clay. Mining in a wider sense means extraction of any resource such as petroleum, natural gas, or even water.

Mining is one of the most destructive practices done to the environment as well as one of the main causes of deforestation. In order to mine, the land has to be cleared of trees, vegetation and in consequence all living organisms that depend on them to survive are either displaced or killed. Once the ground is completely bare, bulldozers and excavators are used to smash the integrity of the land and soil to extract the metals and minerals.

Mining comes in different forms such as open-pit mining. Like the name suggests, is a type of mining operation that involves the digging of an open pit as a means of gaining access to a desired material. This is a type of surface mining that involves the extraction of minerals and other materials that are conveniently located in close proximity to the surface of the mining site. An open pit mine is typically excavated with a series of benches to reach greater depths.

Open-pit mining initially involves the removal of soil and rock on top of the ore via drilling or blasting, which is put aside for future reclamation purposes after the useful content of the mine has been extracted. The resulting broken up rock materials are removed with front-end loaders and loaded onto dump trucks, which then transport the ore to a milling facility. The landscape itself becomes something out of a gnarly science-fiction movie.

Once extracted, the components are separated by using chemicals like mercury, methyl-mercury and cyanide which of course are toxic to say the least. These chemicals are often discharged into the closest water sources available –streams, rivers, bays and the seas. Of course, this causes severe contamination that in turn affects all the living organisms that inhabit these bodies of water. As much as we like to distinguish ourselves from our wild kin this too affects us tremendously, specially people who depend on the fish as their staple food or as a livelihood.

One of the chemical elements that is so in demand in our current economy is Lithium. Lithium battery production today accounts for about 40% of lithium mining and 25% of cobalt mining. In an all-battery future, global mining would have to expand by more than 200% for copper, by a minimum of 500% for lithium, graphite, and rare earths, and far more for cobalt.

Lithium – Isn’t that a Nirvana song?

Lithium is the lightest metal known and it is used in the manufacture of aircraft, nuclear industry and batteries for computers, cellphones, electric cars, energy storage and even pottery. It also can level your mood in the form of lithium carbonate. It has medical uses and helps in stabilizing excessive mood swings and is thus used as a treatment of bipolar disorder. Between 2014 and 2018, lithium prices skyrocketed 156% . From 6,689 dollars per ton to a historic high of 17,000 dollars in 2018. Although the market has been impacted due to the on-going pandemic, the price of lithium is also rising rapidly with spodumene (lithium ore) at $600 a ton, up 40% on last year’s average price and said by Goldman Sachs to be heading for $676/t next year and then up to $707/t in 2023.

Lithium hydroxide, one of the chemical forms of the metal preferred by battery makers, is trading around $11,250/t, up 13% on last year’s average of $9978/t but said by Goldman Sachs to be heading for $12,274 by the end of the year and then up to $15,000/t in 2023. Lithium is one of the most wanted materials for the electric vehicle industry along cobalt and nickel. Demand will only keep increasing if battery prices can be maintained at a low price.

Simply look at Tesla’s gigafactory in the Nevada desert which produces 13 million individual cells per day. A typical Electronic Vehicle battery cell has perhaps a couple of grams of lithium in it. That’s about one-half teaspoon of sugar. A typical EV can have about 5,000 battery cells. Building from there, a single EV has roughly 10 kilograms—or 22 pounds—of lithium in it. A ton of lithium metal is enough to build about 90 electric cars. When all is said and done, building a million cars requires about 60,000 tons of lithium carbonate equivalent (LCE). Hitting 30% penetration is roughly 30 million cars, works out to about 1.8 million tons of LCE, or 5 times the size of the total lithium mining industry in 2019.

Considering that The United States-Mexico-Canada Agreement (USMCA) is being negotiated, lithium exploitation is a priority as a “must be secured” supply chain resource for the North American corporate machine. In 3 years, cars fabricated in these three countries must have at least 75% of its components produced in the North American region so they can be duty-free. This includes the production of lithium batteries that could also become a profitable business in Mexico.

Sonora on Lithium

In the mythical Sierra Madre Occidental (“Western Mother” Mountain Range) which extends South of the United States, there is a small town known as Bacadéhuachi. This town is approximately 11 km away from one of the biggest lithium deposits in the world known as La Ventana. At the end of 2019, the Mexican Government confirmed the existence of such a deposit and announced that a concession was already granted on a joint venture project between Bacanora Minerals (a Canadian company) and Gangfeng Lithium (a Chinese company) to extract the coveted mineral. The news spread and lots of media outlets and politicians started to refer to lithium as “the oil of the future.”

I quote directly the from Bacanora Lithium website:

Sonora Lithium Ltd (“SLL”) is the operational holding company for the Sonora Lithium Project and owns 100% of the La Ventana concession. The La Ventana concession accounts for 88% of the mined ore feed in the Sonora Feasibility Study which covers the initial 19 years of the project mine life. SLL is owned 77.5% by Bacanora and 22.5% by Ganfeng Lithium Ltd.

Sonora holds one of the world’s largest lithium resources and benefits from being both high grade and scalable. The polylithionite mineralisation is hosted within shallow dipping sequences, outcropping on surface. A Mineral Resource estimate was prepared by SRK Consulting (UK) Limited (‘SRK’) in accordance with NI 43-101.”

The Sonora Lithium Project is being developed as an open-pit strip mine with operation planned in two stages. Stage 1 will last for four years with an annual production capacity of approximately 17,500t of lithium carbonate, while stage 2 will ramp up the production to 35,000 tonnes per annum (tpa). The mining project is also designed to produce up to 28,800 tpa of potassium sulfate (K2SO4), for sale to the fertilizer industry.

On September 1st, 2020, Mexico’s President, Andres Manuel Lopez Obrador, dissolved the Under-secretariat of Mining as part of his administration’s austerity measures. This is a red flag to environmental protection as it creates a judicial void which foreign companies will use to allow them greater freedom to exploit more and safeguard less as part of their mining concession agreements.

Without a sub-secretariat, mediation between companies, communities and environmental regulations is virtually non-existent. Even though exploitation of this particular deposit had been adjudicated a decade ago under Felipe Calderon’s administration, the Mexican state is since then limited to monitoring this project. This lack of regulatory enforcement will catch the attention of investors and politicians who will use the situation to create a brighter, more profitable future for themselves and their stakeholders.

To my mind there is a bigger question – how will Mexico benefit from having one of the biggest deposits of lithium in the world? Taking into account the dissolution of the Mining sub-secretariat and the way business and politics are usually handled in Mexico, I do wonder who will be the real beneficiaries of the aforementioned project.

Extra Activism

Do not forget, mining is an integral part of our capitalist economy; mining is a money making business – both in itself and as a supplier of materials to power our industrial civilization. Minerals and metals are very valuable commodities. Not only do the stakeholders of mining companies make money, but governments also make money from revenues.

There was a spillage in the Sonora river in 2014. It affected over 22,000 people as 40 million liters of copper sulfate were poured into its waters by the Grupo Mexico mining group. Why did this happen? Mining companies are run for the profit of its stakeholder and it was more profitable to dump poison into the river than to find a way to dispose it with a lower environmental impact. Happily for the company stakeholders, company profit was not affected in the least.

Even though the federal Health Secretariat in conjunction with Grupo México announced in 2015 the construction of a 279-million-peso (US $15.6-million) medical clinic and environmental monitoring facility to be known as the Epidemiological and Environmental Vigilance Unit (Uveas) to treat and monitor victims of the contamination, until this day it has not been completed. The government turned a blind eye to the incident after claiming they would help. All the living beings near the river are still suffering the consequences.

Mining is mass extraction and this takes us to the practice of “extractivism” which is the destruction of living communities (now called “resources”) to produce stuff to sell on the world market – converting the living into the dead. While it does include mining – extraction of fossil fuels and minerals below the ground, extractivism goes beyond that and includes fracking, deforestation, agro-industry and megadams.

If you look at history, these practices have deeply affected the communities that have been unlucky enough to experience them, especially indigenous communities, to the advantage of the so-called rich. Extractivism is connected to colonialism and neo-colonialism; just look at the list of mining companies that are from other countries – historically companies are from the Global North. Regardless of their origins, it always ends the same, the rich colonizing the land of the poor. Indigenous communities are disproportionately targeted for extractivism as the minerals are conveniently placed under their land.

While companies may seek the state’s permission, even work with them to share the profits, they often do not obtain informed consent from communities before they begin extracting – moreover stealing – their “resources”. The profit made rarely gets to the affected communities whose land, water sources and labor is often being used. As an example of all of this, we have the In Defense of the Mountain Range movement in Coatepec, Veracruz. Communities are often displaced, left with physical, mental and spiritual ill health, and often experience difficulties continuing with traditional livelihoods of farming and fishing due to the destruction or contamination of the environment.

Cristopher Straffon Marquez a.k.a. Straquez is a theater actor and language teacher currently residing in Tijuana, Baja California, Mexico. Artist by chance and educator by conviction, Straquez was part of the Zeitgeist Movement and Occupy Tijuana Movement growing disappointed by good intentions misled through dubious actions. He then focused on his art and craft as well as briefly participating with The Living Theatre until he stumbled upon Derrick Jensen’s Endgame and consequently with the Deep Green Resistance: Strategy to Save the Planet both changing his mind, heart and soul. Since then, reconnecting with the land, decolonizing the mind and fighting for a living planet have become his goals.

by DGR News Service | Apr 17, 2021 | Agriculture, Biodiversity & Habitat Destruction, Climate Change, Colonialism & Conquest, Education, Human Supremacy, Lobbying, Mining & Drilling, Movement Building & Support, Strategy & Analysis, Toxification

Join Us Today

Derrick Jensen, Lierre Keith, Max Wilbert, and grassroots organizers from around the world for a special 3-hour live streaming event, Ending The Greenwashing, starting at 1pm Pacific Time and hosted by Deep Green Resistance.

This event will explore in detail the topic of greenwashing.

Around the planet, mining companies, energy producers, automakers, engineering firms, and investors are gearing up for a new industrial revolution: the “green economy” transition. Trillions of dollars in public subsidy are being redirected to support this. Climate change is a crisis, and fossil fuels must be stopped. But will this project actually help the planet?

The evidence, to be frank, isn’t good.

From north to south, east to west, “renewable” energy operations are bulldozing rare ecosystems, trampling community rights, and looking far too similar to fossil fuels for comfort. The promise of a “green” industrial economy is rapidly being revealed as an illusion meant to generate profits and prevent us from recognizing the truth: that we need fundamental, revolutionary changes in our economy and culture — not just superficial changes to our energy sources.

This event will introduce you to on-the-ground campaigns being waged around the planet, introduce various strategies for effective organizing, and rebut false solutions through readings of the new book Bright Green Lies: How the Environmental Movement Lost Its Way and What We Can Do About It, and discuss philosophy of resistance. There will be opportunities to ask questions and participate in dialogue during the event.

The mainstream environmental movement is funded mainly by foundations which don’t want revolutionary change.

Radical organizations like Deep Green Resistance therefore rely on individual donors to support activism around the world, which is why Ending The Greenwashing is also a fundraiser. We’re trying to raise funds to support global community organizing via our chapters, fund mutual aid and direct action campaigns, and make our core outreach and organizational work possible.

Whether or not you are in a financial position to donate, we hope you will join us today on April 17th for this event!

Facebook event: https://www.facebook.com/events/5248823575192797/

Event will be live streamed on this page: https://givebutter.com/endthegreenwash

by DGR News Service | Apr 11, 2021 | Biodiversity & Habitat Destruction, Climate Change, Lobbying, Mining & Drilling, Movement Building & Support, Strategy & Analysis, The Problem: Civilization

This April 17th,

join Derrick Jensen, Lierre Keith, Max Wilbert, and grassroots organizers from around the world for a special 3-hour live streaming event, Ending The Greenwashing, starting at 1pm Pacific Time and hosted by Deep Green Resistance.

This event will explore in detail the topic of greenwashing.

Around the planet, mining companies, energy producers, automakers, engineering firms, and investors are gearing up for a new industrial revolution: the “green economy” transition. Trillions of dollars in public subsidy are being redirected to support this. Climate change is a crisis, and fossil fuels must be stopped. But will this project actually help the planet?

The evidence, to be frank, isn’t good.

From north to south, east to west, “renewable” energy operations are bulldozing rare ecosystems, trampling community rights, and looking far too similar to fossil fuels for comfort. The promise of a “green” industrial economy is rapidly being revealed as an illusion meant to generate profits and prevent us from recognizing the truth: that we need fundamental, revolutionary changes in our economy and culture — not just superficial changes to our energy sources.

This event will introduce you to on-the-ground campaigns being waged around the planet, introduce various strategies for effective organizing, and rebut false solutions through readings of the new book Bright Green Lies: How the Environmental Movement Lost Its Way and What We Can Do About It, and discuss philosophy of resistance. There will be opportunities to ask questions and participate in dialogue during the event.

The mainstream environmental movement is funded mainly by foundations which don’t want revolutionary change.

Radical organizations like Deep Green Resistance therefore rely on individual donors to support activism around the world, which is why Ending The Greenwashing is also a fundraiser. We’re trying to raise funds to support global community organizing via our chapters, fund mutual aid and direct action campaigns, and make our core outreach and organizational work possible.

Whether or not you are in a financial position to donate, we hope you will join us on April 17th for this event!

Facebook event: https://www.facebook.com/events/5248823575192797/

Event will be live streamed on this page: https://givebutter.com/endthegreenwash

by DGR News Service | Mar 26, 2021 | Biodiversity & Habitat Destruction, Colonialism & Conquest, Indigenous Autonomy, Mining & Drilling, Repression at Home, The Problem: Civilization, Toxification, White Supremacy

DGR stands in strong solidarity with indigenous peoples worldwide. We acknowledge that they are victims of the largest genocide in human history, which is ongoing. Wherever indigenous cultures have not been completely destroyed or assimilated, they stand as relentless defenders of the landbases and natural communities which are there ancestral homes. They also provide living proof that not humans as a species are inherently destructive, but the societal structure based on large scale monoculture, endless energy consumption, accumulation of wealth and power for a few elites, human supremacy and patriarchy we call civilization.

This article originally appeared on Mongabay.

by Hyury Potter and Fabio Bispo on 17 March 2021 |

Translated by Claudia Horn

- The Amazônia Minada reporting project has revealed 1,265 pending requests to mine in Indigenous territories in Brazil, including restricted lands that are home to isolated tribes.

- Brazil’s federal agency for Indigenous affairs, Funai, holds 114 reports of isolated tribes, of which 43 are within Indigenous lands targeted by mining.

- In addition to the spread of diseases such as COVID-19 and malaria, mining activity poses health threats from the mercury used in gold extraction, which contaminates rivers and fish.

- Indigenous groups have filed a lawsuit with Brazil’s Supreme Federal Court against the government, demanding protection for isolated Indigenous peoples.

With much of the world under some kind of lockdown over the past year, working from home has become the default for many. But not for miners in Brazil, who have stepped up their efforts to start exploiting Indigenous territories in the Amazon, including areas that are home to isolated tribes.

Mining on demarcated Indigenous lands is prohibited under Brazil’s Constitution, but that didn’t stop miners from filing 143 requests last year, the highest number in 24 years, with the National Mining Agency (ANM). Of those requests, 71 are for areas where isolated Indigenous tribes live, according to data from Funai, the federal agency for Indigenous affairs. Indigenous activists and researchers warn that isolated groups have no contact with society and are highly vulnerable to any disease brought from outside.

In a lawsuit filed with the Supreme Federal Court last July, the Articulation of the Indigenous Peoples of Brazil (APIB) and eight political parties denounced illegal mining in areas of identified isolated peoples. They called on the federal government to adopt measures and avert what they called a “real risk of genocide” due to the COVID-19 pandemic. Yet even as the pandemic was entering its fifth month in Brazil, the lawsuit revealed the government had not implemented any protective measures in several areas that are home to isolated peoples.

The threat from mining, which can bring disease into rural forest areas, becomes tangible when considering the hundreds of requests from mining companies to operate on lands where isolated peoples live. Of the 114 reports of isolated peoples that Funai holds, 43 are within 26 Indigenous territories in the Amazon. These same territories are targeted by at least 1,265 requests for prospecting or mining activities, according to mapping data from the Amazônia Minada reporting project as of Jan. 29 this year.

“Isolated peoples have a strong connection with their environment,”

says Leonardo Lenin, who worked for 10 years with Funai’s unit for isolated ethnic groups, and who is currently executive secretary of the Observatory of Human Rights of Isolated Peoples and Recent Contact (OPI).

“Any invasion has a violent impact on their lives because the land is what guarantees their well-being,” he says.

Luísa Pontes Molina is an anthropologist who investigates illegal mining in the Indigenous Munduruku territories in the state of Pará. She warns of the health risks that mining poses to Indigenous peoples. In addition to spreading diseases such as malaria and COVID-19, mines harm the environment. Liquid mercury, used to bind gold particles, contaminates the rivers and fish that Indigenous communities depend on, according to a recent study by the Oswaldo Cruz Foundation (Fiocruz) and WWF Brazil. The study found traces of mercury in the entire population tested in the central region of the Tapajós River in Pará state, which includes the municipalities Itaituba and Trairão where the Munduruku people live.

Molina says there is evidence of isolated people living in the municipality of Jacareacanga, in southwest Pará, which have not been reported to Funai. That region is also the subject of 106 requests for gold mining that overlap with the protected Munduruku Indigenous Territory. Funai records at least one isolated Indigenous community in this area.

“Many communities of the Alto Tapajós have been reporting of and denouncing illegal mining and other crimes in the region since 2015. This also includes invasions near isolated groups. But despite these reports, Funai’s budget for inspection is cut more and more,” Molina says.

She adds she has tracked cases of illegal mining and public enforcement, and found that,

“in October 2020, just 2,000 reais [$345] were allocated toward monitoring and inspection in the region of Tapajós.” The study is still in progress, but preliminary findings suggest “state neglect in fighting illegal mining on indigenous lands,” Molina says.

The Amazônia Minada project, an initiative of the InfoAmazonia journalism outlet, cross-references the location of mining applications filed with ANM against demarcated Indigenous territories in the Amazon. Its Twitter feed, @amazonia_minada, tracks ANM processes in real time and tweets when a new mining application is filed within a protected area of the Amazon.

18 mining requests for restricted lands

Most of the mining requests are for land within demarcated territories where most of the Indigenous inhabitants have already made contact with the outside world but where some groups also live in isolation. But there are also 18 mining applications targeting four protected areas with the special classification “restricted,” which means they have been demarcated based on the presence only of isolated peoples.

Six of these requests were filed by the company Bemisa Holding, controlled by the Opportunity Group. Its owner, banker Daniel Dantas, was investigated for financial crimes and convicted in 2008 on bribery charges, but was acquitted in 2016 on a technicality. All six of Bemisa’s mining requests are for copper prospecting on Piripkura land in the state of Mato Grosso. Although the territory was declared restricted in September 2008, ANM in the preceding months still granted exploration permits for the company’s six applications, valid until 2012. On Jan. 19, 2021, the Piripkura land became the target of another application for gold mining, filed by the Miner Cooperative of Vale do Guaporé.

The isolated Piripkura people first made contact with the outside world in 1989, when Funai worker Jair Candor encountered two of the community members who had remained on their land after invasions by outsiders. Over the next three decades, there have been 14 contacts with these two individuals. According to Candor’s account in the documentary Piripkura, evidence of traces of their life in the area guarantees the sustained restriction of the land. Any sign of the pair’s track is photographed proof. All the material is kept secret so as not to reveal the location of the area; the two men are believed to be the last members of the Piripkura ethnic group.

Mining giant Vale, responsible for the two biggest mining-related disasters in Brazilian history, in Mariana and Brumadinho, requested access to the territory of the isolated Tanaru, in Rondônia state. Its application to mine platinum came in 2003, three years before the territory was officially declared restricted. However, the ANM system shows the company managed to unblock the application in 2018. There is no record of ANM’s approval of this application.

Last year, Vale announced to its shareholders that it would abandon all its mining applications within Indigenous lands, only to back down right after.

It has more than 200 active applications within Indigenous lands, 62 in areas where isolated peoples live. Two applications are in the land of the isolated Ituna/Itatá nation in southwest Pará, through the company Mineração Santarém Ltda.

Vale has denied having any active mining bids in the Tanaru and Ituna/Itatá territories, saying that the processes “are no longer pursued by the company since 1989.” Although ANM records show 200 applications on behalf of the group and its various ventures, Vale says “most of these processes were dropped by Vale itself, while pending approval by the ANM.” However, application number 886.223/2003 in the ANM registry, which intersects with the Tanaru Indigenous Territory, does not indicate Vale has given up on its request to mine there.

The Ituna/Itatá land spans 1,420 square kilometers (548 square miles), about the size of São Paulo, Brazil’s biggest city. It was declared restricted in 2011, following three decades during which Funai workers collected evidence of the presence of isolated indigenous peoples. However, the territory is a constant target of miners, landowners, ranchers and politicians. Zequinha Marinho, a senator from Pará, has even requested the end of the restricted status for the Ituna/Itatá Indigenous Territory through a legislative decree, saying there are no isolated tribes in the region according to “knowledge of the facts.”

In February 2020, an anthropologist linked to the administration of President Jair Bolsonaro was arrested for entering the Ituna/Itatá protected area without authorization. He had tried to block an intervention by the federal environmental agency, IBAMA, to remove cattle from the land. In November 2020, the Federal Public Ministry in Pará (MPF-PA) also recommended the suspension of an expedition by Funai. According to the agency, any entry into the area should only be allowed after the removal of invaders who had occupied the Indigenous land and who presented a threat to the life and security of public officials as well.

“You have to leave the Indigenous people in their territory, but that doesn’t happen. What we usually see is permissiveness from the state,”

says a Funai official who spoke on condition of anonymity.

“The Ituna/Itatá lands, for example, are being taken over by squatters. Precisely because they are isolated, these people will not be vaccinated. The precaution with them must be permanent in regard to COVID-19 and any other disease that a miner or squatter can transmit,” the official says.

Denialism and indifference

In July 2020, when Indigenous organizations were already counting nearly 400 Indigenous victims of COVID-19, APIB and eight parties filed a lawsuit with the Supreme Federal Court to force the government to protect Indigenous peoples. Justice Luís Roberto Barroso ordered emergency “situation room” meetings: one for Indigenous peoples and another specifically to monitor regions of isolated peoples and peoples of recent contact.

The meeting on measures for isolated peoples was coordinated by the Institutional Security Cabinet (GSI) of the president’s office, and denounce as “mild” by Beto Marubo, a representative of APIB and leader of the Union of Indigenous Peoples of the Javari Valley (Univaja).

“By calling on the Supreme Federal Court, we hoped to end the denialism of the Bolsonaro government, but it is clear that this has not happened and will not happen,” Marubo said. “The situation room meetings are coordinated by GSI members who have no idea how to protect an isolated Indigenous community. In practice, they are indifferent.”

At the end of July, with Brazil on track for the most COVID-19 deaths after only the U.S., the GSI admitted in a petition to the court that eight Indigenous lands did not have any kind of barrier to prevent people from entering. Three of them are home to isolated peoples: Alto Rio Negro (in Amazonas state), Alto Turiaçu (Maranhão), and Enawenê Nawê (Mato Grosso).

Eight months since APIB filed its lawsuit with the court, and with the COVID-19 death toll among Brazil’s Indigenous people at more than 1,000, the Bolsonaro government has presented no protection plans that Indigenous organizations, medical experts from Fiocruz, and other associations have been able to approve. Three versions have been rejected by Justice Barroso, and a fourth is under consideration.

Indigenous rights activists warn the scenario may only get worse, citing a bill proposed by the Bolsonaro administration that aims to allow mining activity on Indigenous lands. This bill, known as 191/2020 , was shelved last year by Rodrigo Maia, the speaker of the lower house of Congress at the time. But there are fears that it will be revived under the newly inaugurated speaker, Arthur Lira, whose campaign was supported by Bolsonaro.

On Feb. 15, Bolsonaro told supporters and the press during an event in São Francisco do Sul, Santa Catarina state, that “we have to regularize” the exploitation of Indigenous lands. He said it would be “very good because Indigenous people are no longer people who are living isolated, but they are integrating more and more into society.”

That same day, Mongabay requested clarification from the federal agencies ANM, Funai and GSI; as well as from Bemisa Holding. We received no responses from any of them by the time this report was originally published in Portuguese.

UPDATE

On February 15, we asked for a response from Bemisa on the processes mentioned in the report, but there was no feedback. After the publication of this article on March 17, the mining company wrote to Mongabay and informed that in 2011 it asked to waive the six requirements at Piripkura Indigenous Land, in Mato Grosso state. However, all processes are still active in the ANM system and on behalf of Bemisa.

This report is part of Amazônia Minada, a special project of InfoAmazonia with support from the Rainforest Journalism Fund/Pulitzer Center.

This story was first reported by Mongabay’s Brazil team and published here on our Brazil site on March 2, 2021.