![Tribal Members Aim to Stop Lithium Nevada Corporation From Digging Up Cultural Sites in Thacker Pass [Dispatches from Thacker Pass]](https://dgrnewsservice.org/wp-content/uploads/sites/18/2021/06/SageGrouse-980x667-1.jpg)

by DGR News Service | Jun 15, 2021 | Biodiversity & Habitat Destruction, Colonialism & Conquest, Lobbying, Mining & Drilling

Fort McDermitt, Nevada – As soon as July 29, 2021, Lithium Nevada Corporation (LNC) plans to begin removing cultural sites, artifacts, and possibly human remains belonging to the ancestors of the Paiute and Western Shoshone peoples for the proposed Thacker Pass open pit lithium mine.

According to a motion for preliminary injunction filed by four environmental organizations in the case Western Watersheds Project v. United States Department of the Interior, LNC intends to begin “mechanical trenching” operations at seven undisclosed sites within the project area, each up to “40 meters” long and “a few meters deep.” The corporation also plans to dig up to 5 feet deep at 20 other undisclosed sites, all pursuant to a new historical and cultural resources plan that has never been subject to meaningful, government-to-government consultation with the affected Tribes or to National Environmental Policy Act analysis.

Daranda Hinkey, Fort McDermitt Paiute and Shoshone tribal member and secretary of a group formed by Fort McDermitt tribal members to stop the mine, Atsa Koodakuh wyh Nuwu (People of Red Mountain) states: “From an indigenous perspective, removing burial sites or anything of that sort is bad medicine. Our tribe believes we risk sickness if we remove or take those things. We simply do not want any burial sites in Thacker Pass or anywhere in the surrounding area to be taken. The ones who passed on were prayed for and therefore should stay in their place, no matter what. We need to respect these places. The people at Lithium Nevada wouldn’t go and dig up their family gravesite because they found lithium there, so why are they trying to do that to ours?”

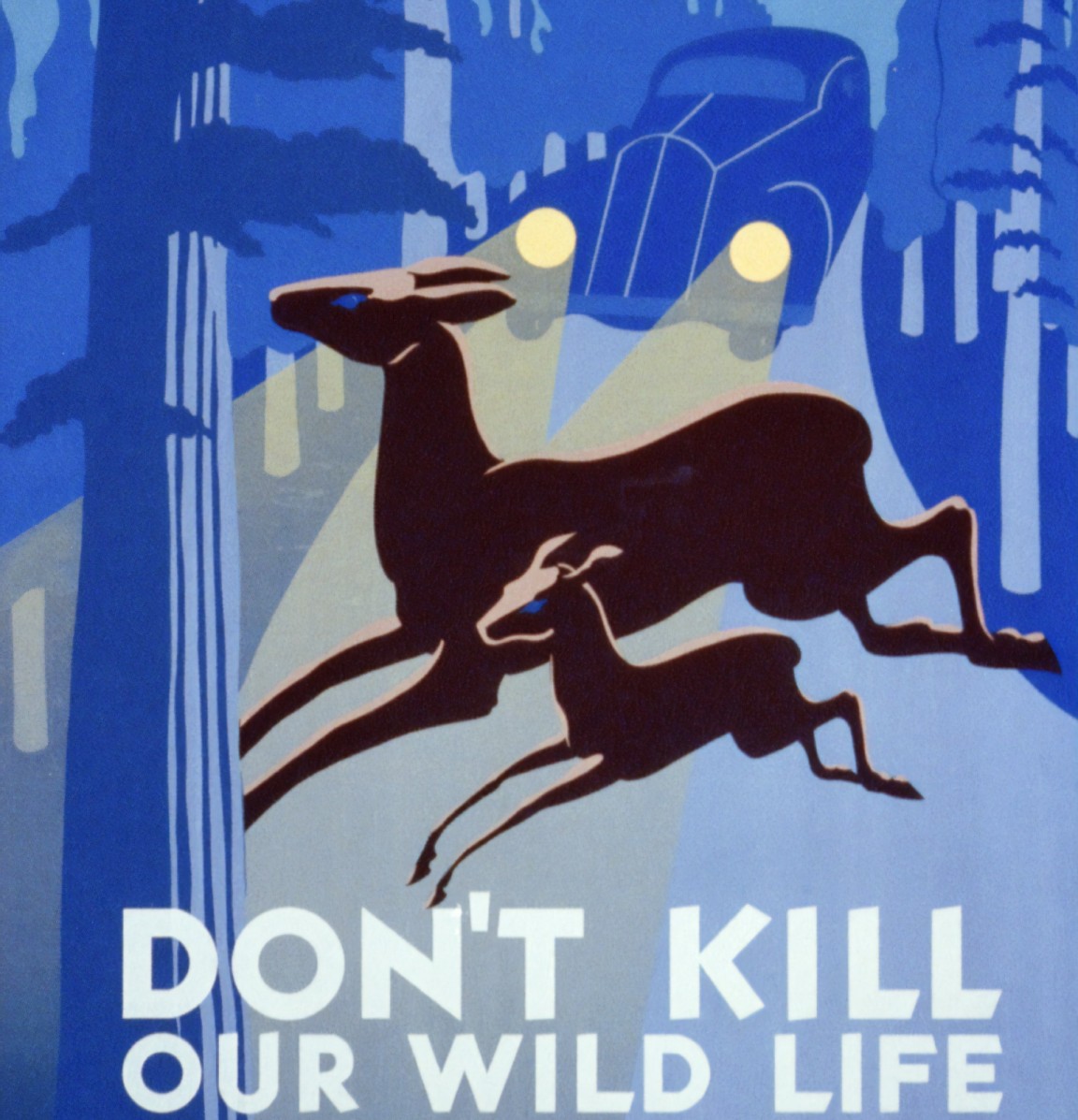

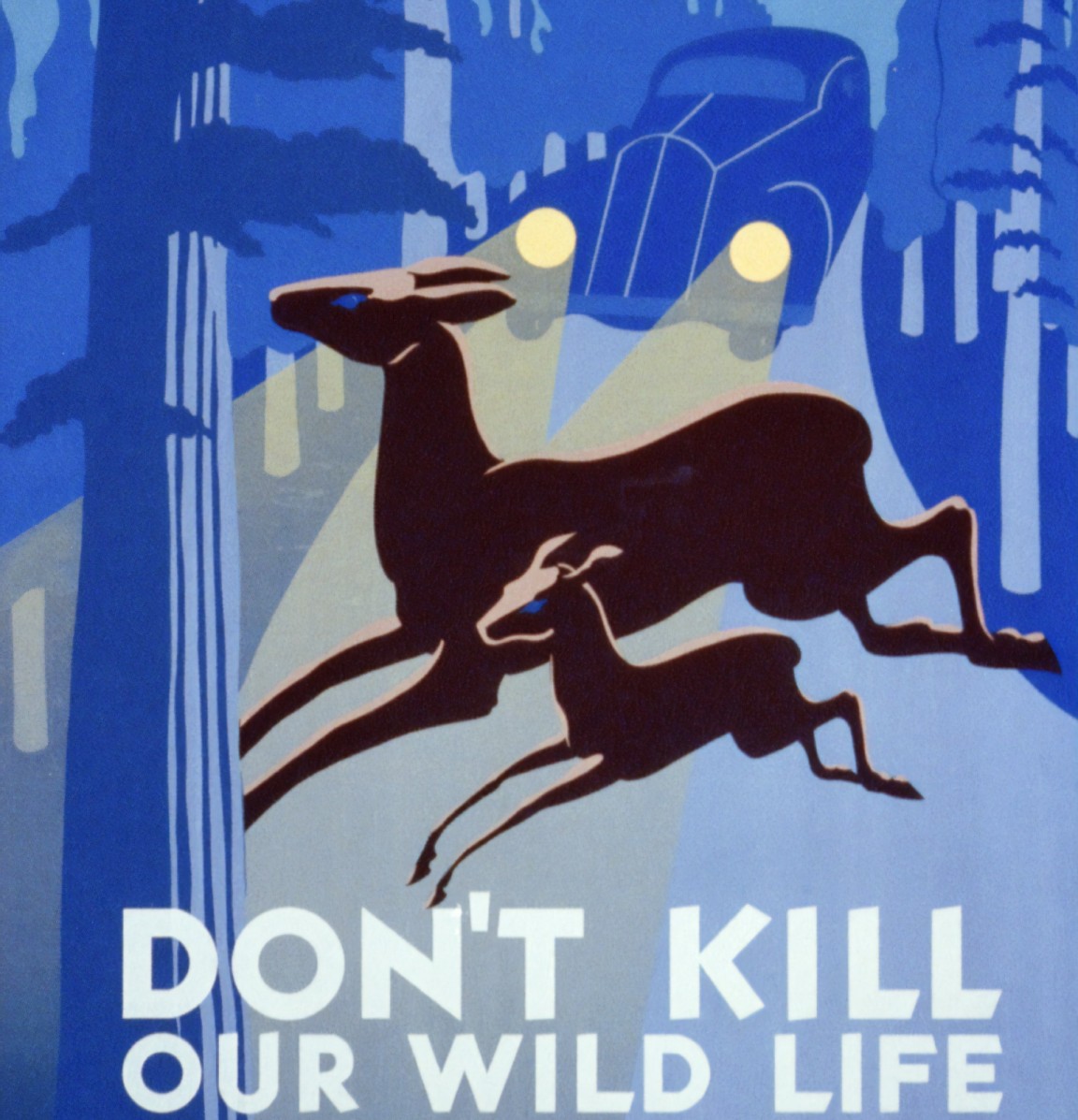

LNC’s Thacker Pass open pit lithium mine would harm the Fort McDermitt Paiute and Shoshone Tribe, their traditional land, and traditional foods like choke cherry, yapa, ground hog, and mule deer. It would also harm water, air, and wildlife including sage grouse, Lahontan cutthroat trout, pronghorn antelope, and sacred golden eagles.

Thacker Pass is named Peehee mu’huh in Paiute. Peehee mu’huh means “rotten moon” in English and was named so because Paiute ancestors were massacred there while the hunters were away. When the hunters returned, they found their loved ones murdered, unburied, rotting, and with their entrails spread across the sage brush in a part of the Pass shaped like a moon. According to the Paiute, building a lithium mine over this massacre site at Peehee mu’huh would be like building a lithium mine over Pearl Harbor or Arlington National Cemetery.

Land and water protectors have occupied the Protect Thacker Pass camp in the geographical boundaries of LNC’s open pit lithium mine since January 15. Will Falk, attorney and Protect Thacker Pass organizer, says: “Our allies, the People of Red Mountain, do not want to see their ancestors disturbed and their sacred land destroyed. We plan on stopping Lithium Nevada and BLM from digging these cultural sites up.”

On Tuesday, June 15th at 11am PST / 2pm EST, we will be phone banking to Secretary of Interior Deb Haaland (Laguna Pueblo) to ask that she rescind (cancel) the Record of Decision for Thacker Pass, delay the project for consultation, and meet with Atsa Koodakuh wyh Nuwu (People of Red Mountain) to discuss the issues here.

During this phone bank, we will be live streaming a press conference featuring Fort McDermitt tribal members and other concerned people. Please join us by filling out the information on this form and join us to #ProtectPeeheeMu’huh / #ProtectThackerPass!

SIGN UP HERE: https://forms.gle/z4Y2w2dKaw7WMHwE6

Event hosted by People of Red Mountain, One Source Network, Moms Clean Air Force, and Protect Thacker Pass. Please share widely!

For more on the Protect Thacker Pass campaign

#ProtectThackerPass #NativeLivesMatter #NativeLandsMatter

by DGR News Service | Jun 12, 2021 | Biodiversity & Habitat Destruction, Climate Change

This article originally appeared on Counterpunch.

BY GEORGE WUERTHNER

In a recent May 29 Bend Bulletin article, Senator Merkley asserted he “wants to boost spending on forest management by $1 billion annually through work, such as thinning and prescribed burning, to reduce the prospects of catastrophic wildfires.”

An unexamined assumption is that thinning/logging work significantly reduces the pejoratively named “catastrophic” fires.

The Holiday Farm Fire burned the western slopes of the Cascades driven by extreme fire weather conditions, including high winds, charred acres of clearcuts, and other “fuel reductions.” Photo George Wuerthner.

Despite assertions from the Forest Service and others who will gain financially from inflated budgets to log our forests, one needs to ask if “fuel reductions” work to halt wildfires when burning under extreme fire weather conditions. That qualifier is important. All large blazes, like those that charred the western Cascades last Labor Day, burn swiftly through logged sites and other “fuel reductions.”

All such blazes occur under drought conditions, high temps, low humidity, and high winds. Thinning/logging and prescribed fires will not significantly preclude large blazes burning under extreme fire weather conditions.

This fire in the Scratchgravel Hills by Helena, Montana, driven by 50 mph, burned through this forest that had been thinned just six months prior to the blaze. Photo George Wuerthner.

I have traveled extensively around the West to view the aftermath of the largest fires, and every single one occurred during extreme fire weather conditions. Nothing, including thinning, logging, and prescribed burns, works to contain such fires when you have these conditions. I know of no exceptions.

Such blazes are only contained when the weather conditions change. Logging does not change the weather.

When it “appears” that fuel reductions worked under extreme conditions, you need to examine the actual burn circumstances during the blaze—the intensity of fire changes hour by hour.

Proponents of forest thinning, including Merkley, suggest previous thinning projects saved Sisters, Oregon from the 2017 Milli Fire that burned within 2-3 miles of town. Yet if you read the Fire Incident Report carefully, such conclusions are questionable.

Thinned ponderosa pine stand near Sisters, Oregon, has resulted in a mono-culture of nearly even-aged forest that degrades the forest ecosystem and doesn’t stop fires burning under extreme fire weather. Thinning kills trees to preclude natural processes from killing trees. Photo George Wuerthner.

The Milli Fire burned through two previous burns (Pole Creek and Black Crater), presumably “fuel reductions.” It also burned through some thinned stands before thinning “saved” Sisters.

The red outline shows the wind-driven effect of the Milli Fire. A change in wind direction “saved” Sisters—photo USFS.

What happened is that the wind that had been moving the fire towards Sisters shifted, pushing the fire west and north into lava fields in the Three Sisters Wilderness.

Did thinning save Sisters? Maybe? However, a more nuanced analysis might conclude that a change in weather patterns is what “saved” Sisters.

Worse for our communities is that the Forest Service is “selling” a myth. Thinning/logging has been shown to increase fire spread. Thinning opens the forest to more wind penetration and more soil drying—both factors are conducive to fire spread during extreme fire weather.

Logging/thinning on the Deschutes NF leaves many fine fuels on the ground, often exacerbating fire spread. Photo George Wuerthner.

What burns in wildfires are the fine fuels: grass, shrubs, pine needles, small trees, and so forth. Large trees that thinning removes typically do not burn. That is why we have “snags” after a severe fire.

While thinning and prescribed burning treatments might lower fire intensity briefly immediately after the treatment, the chances that a fire will encounter a treatment is extremely rare.

Ironically, fuel reduction often increases the percentage of fine fuels on a site, ensuring that a blaze can readily spread if driven by high winds.

Ignored in the race to log our forests is that high severity fires are essential to healthy forest ecosystems. The biodiversity they produce often exceeds what is found in “green forests.”

Snags are critical to a healthy forest ecosystem. This is a sign of forest “health.” Photo George Wuerthner.

So the “story” the FS sells that thinning is “improving” forest health is another inaccurate statement. Dead trees resulting from fires, bark beetles, and other natural factors are critical to healthy forest ecosystems.

A sanitized forest stand (restoration) on the Deschutes NF, Oregon. Note the lack of small trees, lack of species diversity, lack of snags, down wood, and even shrubs. Photo George Wuerthner.

Thinning/logging is not benign. There are many impacts to the forest ecosystem from “restoration,” “fuel reductions,” and other euphemisms used to justify commercial logging. These include the spread of weeds, sedimentation in streams from logging roads, displacement of sensitive wildlife, loss of biomass, and loss of carbon storage.

Ultimately, we must deal with the GHG emissions that drive climate change, increasing drought, variable weather, and the conditions that favor large blazes.

In the meantime, increasing thinning and prescribed burning, except in the immediate area around communities, does little to protect homes. A much better way to spend scarce funds is to assist communities and homeowners in reducing the flammability of homes, burying power lines, and precluding new home construction in fire-prone areas.

George Wuerthner has published 36 books including Wildfire: A Century of Failed Forest Policy. He serves on the board of the Western Watersheds Project.

by DGR News Service | Mar 23, 2021 | Agriculture, Biodiversity & Habitat Destruction, Climate Change, The Problem: Civilization

In this article, Erik Molvar outlines the serious nature of climate change. He offers evidence-based clarity on why destroying fragile woodlands, that holds carbon in place, needs to stop.

The dawn breaks each morning on a hundred different mountain ranges in the Great Basin, with few human eyes to see it.

Many of these mountain chains will be unfamiliar to most – the Toquimas, the Wah Wahs, the Goshutes, the Sheeprocks, the Fox Range – but the one thing they all have in common is their juniper woodlands that have been here for thousands of years. On the mesas and tablelands of the Colorado Plateau, guarding the slickrock canyons and mazes of badlands that are American icons, are the fragile woodlands (don’t bust the crust!) of pinyon and juniper that perfume the air with that ineffable scent of wild country. Today, just as the world awakens to the reality that we need as much carbon sequestration as possible, these arid woodlands are under assault from a coordinated campaign to deforest the West, orchestrated by the livestock industry.

Action to address climate change has been announced as a central policy priority with the Biden administration, putting the significant role of domestic livestock in climate disruption in the spotlight. Methane emissions (both from the four-chambered digestion system that allows ruminants to digest cellulose, and from the breakdown of manure) get the lion’s share of the attention, in keeping with America’s end-of-tailpipe fixation on measuring pollution. But the carbon cycle is circular, and livestock exacerbate climate disruption at many points in the cycle. One key effect is by bankrupting soil carbon reserves by eliminating deep-rooted perennial plants and replacing them with annual weeds, and another is through deforestation to create cattle pasture. While deforestation for livestock is widely-recognized as a major climate problem in the Amazonian rainforests, deforestation of pinyon-juniper woodlands is ramping up across the American West, and similarly contributes to the climate catastrophe.

The real reason that pinyon-juniper woodlands are so aggressively targeted for “control” and “treatment,” even though they are an ecologically important and natural component of western ecosystems, comes down to the almighty dollar. A recent survey of Bureau of Land Management employees by Public Employees for Environmental Responsibility contains this clue: “with ranchers, one employee noted that the current excuse to cut pinyon juniper and sagebrush to prevent wildfire, which have been the native species for thousands of years, has no scientific reasoning. Instead, it’s to benefit cattle.”

During the dying days of the Trump administration, an all-out war on juniper woodlands was underway under the guise of fire prevention. The Tri-State Fuel Breaks Project planned almost a thousand miles of strips; scientists criticized the project, predicting it

“will not achieve success and may in fact exacerbate degradation of the native flora and fauna of the region.”

The Idaho portion was approved in May of 2020, authorizing

“manual, mechanical, and chemical treatments, along with targeted grazing and prescribed fire.”

The Great Basin Fuel Breaks Project was even bigger, authorizing 11,000 miles of fuel breaks in April of 2020. The selected alternative authorized wiping out 121,000 acres of woodlands. And for what? A federal review of the science found inconclusive benefits from fuel breaks constructed throughout the West over the past five decades. In effect, these are make-work projects that, while causing significant ecosystem destruction and habitat fragmentation, have little or no benefit in reducing the extent or intensity of fires.

Fuel breaks are but the tip of the deforestation iceberg.

In January 2021, during the twilight of the Trump presidency, a program called “Fuels Reduction and Rangeland Restoration for the Great Basin” was completed. Under this plan, more than 26 million acres would be targeted for a variety of environmentally destructive projects euphemistically labeled “vegetation treatments” as if the native vegetation is somehow sick. “Targeted grazing” is one such treatment authorized, even though a federal court ruled that livestock grazing actually increases the spread of flammable cheatgrass, instead of reducing fire risk, after hearing expert testimony on both sides of the issue.

Pinyon-juniper woodlands would bear the brunt of the projects, facing chainsaws, chaining with bulldozers, and herbicides. Some 3,088,468 acres of pinyon-juniper woodlands are now scheduled for “restoration treatments.” The Administration pre-approved this massive program habitat destruction under a single Environmental Impact Statement, which could allow the agency to approve future projects without analyzing the site-specific impacts, or perhaps even public notification.

The drive to get rid of pinyon and juniper woodlands began several years ago.

Senators Hatch and Heinrich slipped a rider into the 2018 Farm Bill instructing the Bureau of Land Management to create a “Categorical Exclusion” exempting pinyon-juniper logging and chaining projects of up to 4,500 acres from having to go through environmental analysis otherwise required by the National Environmental Policy Act. This legislation was pushed by sportsman groups, spearheaded by the Mule Deer Foundation. Western Watersheds Project and other conservationists warned that pinyon-juniper removal was bad for wildlife – including mule deer – but these warnings were ignored by Congress. Ironically, several months after Hatch-Heinrich passed, a new scientific study was published demonstrating that pinyon-juniper woodlands were an essential habitat component for mule deer, and that juniper removals have a negative effect on the species.

Then the Trump administration took it a giant leap farther, authorizing that pinyon-juniper removals as large as 10,000 acres could be approved under a Categorical Exclusion.

Cutting down juniper woodlands is often promoted as a method to create or improve habitat for the imperiled sage grouse, which requires undisturbed sagebrush steppe habitats and avoids trees of any kind. While juniper removal might seem to make sense, the reality is that logged-off juniper woodlands seldom result in sage grouse habitat. Mature and old-growth stands of junipers typically have very little understory at all, neither sagebrush nor native grasses. When bulldozers and other heavy equipment move in and the trees are torn down, what you get is disturbed bare ground. It’s the perfect breeding ground for the non-native invasive weed, cheatgrass.

If the goal is fuel reduction, cheatgrass infestations are the worst possible outcome.

When livestock add their impacts into the mix (as they almost always do), suppressing native bunchgrasses and breaking up fragile soil crusts, cheatgrass proliferates. Highly flammable, cheatgrass predictably dies each July (escaping the drought stress of high summer in seed form). Drying out, it creates the perfect tinder for fires to burn, and those fires wipe out sagebrush and other fire-intolerant shrubs creating a monoculture of cheatgrass that fuels a cycle of frequent wildfires in perpetuity.

There is a widespread myth that pinyon pines and juniper are an “invasive species” that are unnaturally expanding their range as a result of human activities like fire suppression or heavy livestock grazing. The reality is that these woodlands have been expanding and contracting for thousands of years in a natural cycle, following changes in precipitation patterns.

In addition to mule deer, there are a number of other native wildlife species that benefit from pinyon-juniper woodlands. Scott’s oriole, juniper titmouse, and Bewick’s wren are a few of the songbird species that are considered juniper obligates. Pinyon jays are pinyon obligates, as their name suggests. Obligate species are animals that require a specific type of habitat to sustain their populations.

As for the climate impacts, when you replace juniper woodlands – or sagebrush-bunchgrass steppes – with cheatgrass, it reverses the enormous carbon sequestration capability of western desert shrublands, hemorrhaging soil carbon into the atmosphere. We typically think of forests as the most important carbon immobilizers, but desert shrublands can pull even more carbon out of the atmosphere and safely lock it away in the soil.

The removal of pinyon-juniper woodlands across the American West draws a direct parallel with rainforest destruction to create livestock pastures in the Amazon Basin. It’s all about the fool’s errand of trying to mow down native ecosystems and replace them with idyllic grassy pastures ideal for adding pounds and profits to beef cattle. Nevermind that cattle are ill-adapted to arid environments, and do so poorly on western public lands that the vast acreage dedicated to beef production on western federal lands amounts to little more than two or three percent of the nation’s beef production. Even if western public lands had no recreational value to the Americans for whose benefit they are supposed to be managed, the carbon sequestration value of juniper woodlands would still eclipse the scanty private profits that are wrung from marginal western livestock operations.

Climate change is a serious problem, not least of all for the arid West now struggling with protracted drought and decreasing water availability. Let’s stop making it worse by cutting down the fragile woodlands that hold the carbon in place.

This article was written by Eric Molvar and published on Counterpunch on March 12, 2021. You can read the original version here!

Erik Molvar is a wildlife biologist and is the Laramie, Wyoming-based Executive Director of Western Watersheds Project, a nonprofit group dedicated to protecting and restoring watersheds and wildlife on western public lands.

by DGR News Service | Jan 28, 2021 | Biodiversity & Habitat Destruction, Mining & Drilling, Obstruction & Occupation

Activists Occupy Site of Proposed Lithium Mine in Nevada

By Kollibri terre Sonnenblume, originally published by Macska Moksha Press Reproduced here with permission, thank you.

On Friday, January 15th, two activists drove eight hours from Eugene, Oregon, to a remote corner of public land in Nevada, where they pitched a tent in below-freezing temperatures and unfurled a banner declaring:

“Protect Thacker Pass.”

You’ll be forgiven if you’ve never heard of the place—it’s seriously in the boonies—but these activists, Will Falk and Max Wilbert, hope to make it into a household name. One of the activists is Will Falk, a writer and lawyer who helped bring a suit to US District Court seeking personhood for the Colorado River in 2017. He describes himself as a “biophilic essayist” and he certainly lyrical in describing the area where they set up:

“Thacker Pass is a quintessential representation of the Great Basin’s specific beauty. Millions of years ago a vast lake stretched across this land. Now, oceans of sagebrush wash over her. If you let the region’s characteristic stillness settle into your imagination, you’ll see how the sagebrush flows and swells like the ancient lake that was once here. On the north and south ends of the Pass, mountains run parallel to each other. The mountains feature outcroppings of volcanic rock left by the active volcano that was here even before the ancient lake. The mountains cradle you with the valley’s dips and curves up to the ever-changing, never-ending Great Basin sky. During the day, the sun shines down full-strength creating shape-shifting shadows on the mountain faces. At night, the stars and moon shine with such intensity and clarity that you can almost hear the light as it pours to the ground.”

I’ve spent enough time in the Great Basin to attest to its beauty myself: the dramatic ranges, the expansive flats, the gnarled trees, the stiff-stemmed wildflowers, and the lean, sinewy jack rabbits; they are all expressions of endurance in a landscape imbued with the echoes of the ancient. How long ago it must have been, when waves lapped the foothills, yet the shapes they left are unmistakable. The sense is palpable of being elevated, inland, and isolated from the ocean—the waterways here don’t run to the sea, hence the name “basin.”

Austere as it all is, humans have lived in the area for many thousands of years, digging roots, gathering seeds & berries, harvesting pinenuts and hunting game.

These traditions, though assaulted, survive.

To the Europeans seeking fertile valleys to farm or dense forest to cut, the Great Basin offered little to nothing, so most of the folks from “back east” just passed through. But ranching and mining cursed the region since the invasion began, and its grasses were razed and its rocks ripped open. Still, many areas, especially up the slopes, were spared the hammering that befell the tallgrass praries of the Midwest and the old growth forests of the West, which were extirpated to the degree of 95% or more. In fact, some of the last best wildlife habitat in the lower 48 still hangs on in the Great Basin, ragged though it might be around the edges.

Yet it seems the time has come when these “wastelands,” as so many erroneously consider them, will be put on the chopping block for a new kind of exploitation: “green” energy development. Massive solar arrays and huge wind farms have been taking the lead in this latest wave of exploitation, and now mining is being imposed. Not coal for fuel or gold for wealth but lithium for electric car batteries.

The Proposal

Thacker Pass is the site of a proposed lithium mine that would impact nearly 5700 acres—close to nine square miles—and which would include a giant open pit mine over two square miles in size, a sulfuric acid processing plant, and piles of tailings. The operation would use 850 million gallons of water annually and 26,000 gallons of diesel fuel per day. The ecological damage in this delicate, slow-to-heal landscape would be permanent, at least on the human scale. At risk are a number of animal and plant species including the threatened Greater Sage Grouse, Pygmy Rabbits, the Lahontan Cutthroat Trout, a critically imperiled endemic snail species known as the Kings River Pyrg, old growth Big Sagebrush and Crosby’s Buckwheat, to name just those that are locally significant. Also present in the area are Golden Eagles, Pronghorn Antelope, and Bighorn Sheep.

A cultural heritage also exists in this area. In describing the north-south corridor immediately to the east of Thacker Pass, wildtender Nikki Hill says:

“This pass in Nevada is a bridge of great importance. My auntie, Finisia Medrano, would speak of how this was the way one would travel by horse or foot from the wild gardens of Eastern Oregon to continue into Nevada and still be supported, finding food and water for the journey. She would speak of how there was no other real good way to make this crossing, due to a lack of resources in the surrounding landscape. If this is the case for a human, it is the case for all the non human people traversing this area as well. There is so much fragmentation, in landscape, mentality and relations, all stemming from a displaced sense of belonging. How will we know our way back to places, both in spirit and in touch, without threads of continuity to weave together?”

It’s industry vs. ecology once again, and there’s nothing “sustainable” about it for the thousands of creatures who will lose their lives or homes if the mine is allowed to happen.

The reason that Will Falk and his fellow activist Max Wilbert rushed to the site on January 15th was because that’s the day the Bureau of Land Management issued it’s “record of decision,” which greenlighted this horrific project. The BLM considered four alternatives and admitted that it did not choose the “environmentally preferable” one—which was no mine—because it would not have satisfied the “purpose and need”—which was obviously the mine itself. I point this out to illustrate that US land management decisions are primarily made in favor of development not preservation. Typically, what environmental regulations do exist are weak, poorly enforced, and increasingly watered down. Hence, Falk and Wilbert’s decision to take direct action.

This is not the most comfortable time of year to be camped out in northern Nevada, so I admire them for making this choice. Overnight lows are in the teens and twenties at this time of year, and daily highs in the thirties and forties. Snow is possible. But it’s the truth that showing up is often the only way to make a difference.

They sent out a press release on Monday, January 18th, announcing their encampment. Said Falk:

“Environmentalists might be confused about why we want to interfere with the production of electric car batteries.”

Here, Falk is speaking to the fact that over the last twenty years, the focus of mainstream environmentalism has narrowed in on carbon pollution as a central concern, too often to the exclusion of issues like industrial development, technological consumption and other forms of pollution. Specifically, the topic of automobile use has been reduced to a question of emissions when, in reality, cars and car culture are problematic for many other reasons:

- Car-related deaths in the US are typically around 40,000 per year, and far more people are injured, sometimes maimed for life.

- Cars kill countless animals annually in both urban and rural settings. Whether the vehicle is gas-powered or battery-powered doesn’t make a difference to the poor squirrel, cat, coyote, skunk or deer who is taken out.

- Roads themselves demand a tremendous amount of resources for their construction and upkeep. If the cement industry were a country, it would be the third largest emitter of carbon in the world.

- In rural areas, roads fragment habitat, preventing natural pattern of foraging, hunting and migration.

- Car tires contain toxic substances that are harmful to wildlife, and as the Guardian recently reported, Salmon in the Pacific Northwest are being killed by a chemical being washed into rivers and streams by the rain.

- City life is made far less hospitable by the quantity, speed, and dominating presence of cars. Streets and parking lots can take up 50% of a US city. Much of that would be better be used for other purposes like pedestrian plazas, green spaces and urban agriculture.

- Then there are the cultural aspects of car culture. The car-based suburbs struck a terrible blow to localized communities in the US, breaking up close-knit urban neighborhoods and replacing them with atomized subdivisions, in which each household (now reduced to its “nuclear” form, without extended family) was isolated with a propaganda machine. The “conveniences” imposed on us then ended up having a far higher price tag than advertised, and the resulting consumer culture is now swallowing up the world. From a mental health stand point, the alienation the suburbs inflicted on our society still tortures us to this day.

- More subtle, but very real, is the way our perception is shaped by observing the world from inside a metal box at great speed. From a vantage of insulation and separation, other objects—including people—are reduced to mere obstacles. The dehumanization that is imprinted this way doesn’t immediately end when we get out of the vehicle.

Replacing gas stations with charging stations is not going to address any of this. Though the globalized system of extraction that supports all of this is itself running out of fuel, I fear that electric vehicles will only draw out the agony.

Some will argue that electric cars are beneficial regardless of all of the above, because they do reduce emissions while driving, and doesn’t that make them worth it? That’s unclear. The entire calculus must include the damage incurred by lithium mining, and by all the other extractive activities needed specifically for electric cars. The air might indeed be fresher in the city, but at the cost of habitat destruction, pollution and human suffering in another place—in somebody else’s home.

In a statement issued by the Western Watersheds Project about the BLM approving the Thacker Pass lithium mine, Kelly Fuller, their Energy and Mining Campaign Director warned:

“The biodiversity crisis is every bit as dire as the climate crisis, and sacrificing biodiversity in the name of climate change makes no scientific or moral sense. Over the last 50 years, Earth has lost nearly two thirds of its wildlife. Habitat loss is the major cause. Humans can’t keep destroying important wildlife habitat and still avoid ecosystem collapse.”

Human rights issues are also in the mix. Lest we forget, the US-backed right-wing coup in Bolivia in late 2019 was motivated in part by desire to control the lithium deposits in the Andean highlands, a place of otherworldly beauty. (See “Coups-for-Green-Energy added to Wars-For-Oil.”) Though the Bolivian people have since taken back their government, they experienced violence and suffering in the meantime. Unfortunately, the socialist party returned to power also favors mining the lithium. Their model is Venezuela, where oil profits were used to fund social programs. So, US leftists should take note that overthrowing capitalists does not automatically translate into “green” policy.

As Falk said: “It’s wrong to destroy a mountain for any reason – whether the reason is fossil fuels or lithium.”

The real answer, of course, is fewer cars.

Plenty of activists, academics and planners have been talking about how to do that for years, and there’s plenty of solutions to pick from. What’s been lacking so far is the political will and the vibrant movement needed to force that will.

Nikki Hill further commented:

“The answer to the climate crisis is not ramping up new, more, green energy. This ‘green’ is just a word coloring the vision of insatiable growth, peddled by green greed. The green we need so desperately is the one that fills our hearts with connected wonder with the rest of the living world. And that requires slowing the fuck down.”

Indeed. And as of Friday, January 15th, two activists are camped out in Thacker Pass, Nevada, to slow down—and hopefully stop—that insatiable growth.

To follow or support the campaign, visit the Protect Thacker Pass website at protectthackerpass.org or follow them on Facebook or Instagram.

This article draws on a podcast interview I did with Will Falk on January 18th. Listen to it here.

by DGR News Service | Nov 15, 2020 | Strategy & Analysis

In this piece, originally published in Counterpunch, George Wuerthner examines previous successful conservation movements, and describes what we can learn from them.

We do not want those whose first impulse is to compromise. We want no straddlers, for, in the past, they have surrendered too much good wilderness and primeval areas which should never have been lost.

– Bob Marshall on the founding of the Wilderness Society

By George Wuerthner / Counterpunch

There is an unfortunate tendency on the part of conservationists to forget or ignore history. A greater appreciation of past conservation victories as well as defeats can inform current efforts. In far too many cases, there is a tendency to believe that it is necessary to appease local interests typically by agreeing to weakened protections or resource giveaways to garner the required political support for a successful conservation effort. However, this fails to consider that in nearly all cases where effective protective measures are enacted, it has been done over almost uniform local opposition.

In those instances where local opposition to a conservation measure is mild or does not exist, it probably means the proposal will be ineffective or worse—even set real conservation backward.

Nevertheless, many environmentalists now believe that due to regional parochialism and lack of historical context, significant compromises are necessary to win approval for new conservation initiatives.

These compromises demonstrate a failure to learn the lessons from conservation history. In particular, it is striking that in today’s era of greater environmental awareness, many environmentalists are willing to propose compromises that offer far weaker protections for our public lands heritage than what was accomplished decades ago, when resource extraction industries had a much greater influence over local and regional economies.

LESSON ONE: Nearly all worthwhile conservation successes were established over strong local objections. This opposition is not surprising. Current land users have a vested interest in maintaining the status quo. Though environmental protection has been shown repeatedly to provide long term economic and social benefits to regions, those who benefit are often different from those who have a vested interest in maintaining the status quo. We nearly always hear that protection will ruin the local economy.

Thus Yellowstone National Park was created by Congress mainly over the opposition of locals in Montana Territory, who wanted the park to remain open to homesteading, logging, and ranching. Indeed, annually for twenty years after establishing the park, Montana’s Congressional representatives introduced bills into Congress to undesignate the park. Fortunately, due to strong support for the park from the “dreaded eastern establishment,” these efforts did not succeed.

Similarly, when Franklin Roosevelt established Grand Teton National Monument in 1943, Jackson’s local leaders declared that Jackson would become a “ghost town,” and Wyoming’s Congressional delegation introduced a bill to eliminate the park. The bill successfully passed both branches of Congress. The monument only survived because Franklin Roosevelt vetoed the bill.

Early efforts to create a park in the Olympic Mountains with the first park bill were introduced in 1904—a statement that was vigorously opposed by local timber interests. Teddy Roosevelt responded and established the Olympic National Monument in 1907 and put vast tracts of virgin timber off-limits to logging when logging was king.

Nevertheless, opposition from logging interests continued. However, in 1938 outside interests lead to the establishment of Olympic National Park. In the long run, the park’s creation has been shown to have substantial long-term benefits to the residents of the Olympic Peninsula. However, those who made their living by cutting down the Olympic Peninsula trees are not necessarily the same people who are now making a living from the park’s scenic, ecological, and tourism values.

LESSON TWO: Don’t assume all locals are opposed. Typically the most vocal opponents are those with the largest vested interest in maintaining the status quo. There may even be a “silent majority” that is at least neutral or mildly supportive of your proposal, but they are not the ones who control the local politics. However, whether one or many local supporters, nearly all successful conservation efforts rely upon outside leadership to issue a state or national concern. And there is usually some visionary (or group of visionaries) that led this national campaign ala John Muir (Yosemite), David Brower (Dinosaur), Bob Marshall (Gates of the Arctic), Olaus Murie (Arctic Wildlife Refuge), Willard Van Name, Rosalie Edge, and Irving Brant (Olympic), George Dorr (Acadia), etc.

LESSON THREE: Creating and generating the political case for strong conservation protection, as opposed to more limited or weak gains, often takes a while, sometimes a long time. For instance, in the 1930s, Bob Marshall publicly called for protecting all of the Brooks Range north of the Yukon River as a national park. It took until the 1980s for his vision to become a reality. Look at a map of northern Alaska. You will see that nearly the entire Brooks Range is now in some protected status between national wildlife refuges, national preserves, and national parks.

LESSON FOUR: Pragmatists, in the end, leave messes for future generations to clean up. Capitulating to local interests with half-baked compromises in the interest of expediency typically produces uneven results. Either they do not adequately protect the land or create enormous headaches for future conservationists to undue often at a significant political and economic expense.

For instance, when the national forest system was first established, the lands were protected from commercial uses, much like our current national parks. However, in 1905, Gifford Pinchot proposed expanding this system of national forest reserves into national forests, opposition to the forest system from mining companies who wished to use timber from national forests for mining timbers and other mine construction lead to a compromise that permitted commercial logging. Some conservationists like John Muir were opposed to this compromise, but they lost in their efforts. Others felt that a compromise was needed, and besides, it was reasoned such a compromise would be harmless because most of the best timber was outside of the forest preserves and on private lands. No one could imagine there would be much demand for logging on national forest lands.

A similar compromise was also made regarding commercial livestock grazing to win over western ranchers. So commercial logging and ranching were put in place to neutralize western opposition to the forests—but we are still paying the price for that decision today.

Another example is Lake Tahoe—the gem of the Sierras. Initially, there was a movement to protect the lake as a national park. But in the interest of expediency and due to local opposition that wanted to log the great pine forests surrounding the lake, the park proposal was dropped in favor of national forest status. Today many of the problems that plague the Tahoe basin, including water quality decline, are a consequence of this decision, including the abundance of private lands (which could be settled within national forests but not parks).

Point Reyes National Seashore represents another example. The park was created by the purchase of private ranchlands on the Point Reyes Peninsula. As a compromise, any rancher that wanted to remain on their former property and continue ranching/farming was given a 25 year grace period, after which they would be required to leave the property. Almost immediately, the ranchers began to lobby to extend the grace period. Today, fifty years later, they are still operating on the public lands and damaging the water, wildlife, and plant life of the peninsula. Had the Park Service and Congress done what any other property owner does upon purchasing land, which is to pay for the land and have the former owners leave, we would not be facing the prospect of another 20 years of livestock production on these parklands.

We’ll never know whether these compromises were necessary. One could argue that we would not have any national forests today if we had not made such compromises, but this is mostly conjectures. National support for parks and other preserves was very high, and it is likely national forests without logging and grazing would have won Congressional approval.

LESSON FIVE: Over time, most locals view conservation areas as an asset and source of pride. This change typically takes a couple of decades, but I know of no exceptions. Despite this realization that any particular park, wilderness, etc. is overall a benefit to the local and regional society does not typically result in local support for new conservation proposals as they come along. In other words, though people in Montana have grown to love Yellowstone National Park, there was still stiff local opposition to new wilderness areas adjacent to Yellowstone National Park like the Absaroka Beartooth Wilderness when it was created in 1978.

To illustrate one example, I will highlight the chief milestones along the way towards today’s Grand Canyon National Park.

GRAND CANYON

1882. Senator Harrison (later president) introduces three proposals for a Grand Canyon National Park into Congress without success.

1883. Harrison, elected president, creates 15 forest preserves, including one surrounding the Grand Canyon.

1898. Coconino County Board of Supervisors passes resolution opposing new forest preserve—and attempts to have protections lifted.

1903. Teddy Roosevelt visits the canyon.

1906. Roosevelt signs a bill to create a large game range at canyon again over local opposition.

1908. Roosevelt asks his attorney general whether there was any limit on the size of areas that could be protected using the recently passed Antiquities Act (1906). The Act was created to protect “small” sites like Indian ruins. However, according to the attorney general, no size limit exists—so Roosevelt uses the Antiquities Act to create a million-acre Grand Canyon National Monument.

Residents in Arizona were outraged. Arizona’s congressional delegation succeeded in blocking all funding for the implementation of monument protection. They sued the federal government and went all the way to the Supreme Court. They argued that Roosevelt exceeded his powers and the original intention of the Antiquities Act. Supreme Court upholds the use of the Antiquities Act, and Grand Canyon National Monument remains.

Failing to eliminate the monument, opponents took a new tact—like Healthy Forests Initiative—they used the conservationists’ language to hide their real intent—to undercut protection. Knowing the national popular support for parks, in 1917, Arizona Senator Henry Ashurst introduced a bill to make the Grand Canyon a national park.

1919. Grand Canyon NP was signed into law—but freed up much of the valuable mining, timber, and grazing lands to satisfy local interests. The bill removed monument and park protection to grazing and timberlands, reducing the overall acreage protected by the national monument by 2/3!

1927. Growing popular support for parks and the Grand Canyon lead to the expansion of Park boundaries to 646,000 acres.

1932 Herbert Hoover declared a new Grand Canyon NM to protect an additional 273,000 more acres surrounding the existing national park.

1969. Marble Canyon NM was created.

1975. Grand Canyon Enlargement Act adds Marble Canyon and Grand Canyon NM to the existing Grand Canyon National Park. Creating a park of 1.1 million acres that finally equals in size the original national monument that Roosevelt had protected in 1908.

1979. UNESCO declares Grand Canyon, an official World Heritage Site.

In the 1990s, when federal budget issues threatened to close the park to visitors, the state of Arizona offered to pay rangers salaries to keep the park open—illustrating the complete change in attitude that now prevails.

2000 President Clinton designates just over 1 million acres as the Grand Canyon-Parashant National Monument to protect much of the North Rim region of the canyon over locals’ objection. I predict that someday these lands will be added to Grand Canyon National Park.

Conclusion

The most important lesson is not to be discouraged when local people do not widely hold your idea for conservation protection. This should not prompt an immediate compromise to whatever legislation or goal you are pursuing. Instead, stick to the plan, and in many instances, you will prevail. Try to neutralize local opposition, but generate outside support if possible, make the issue a state or national issue.

For instance, it was downstate supporters in New York City that provided the political muscle to create the Adirondack State Park over residents’ objections. This park, now 6 million acres in size, has a clause that prohibits all logging on state lands. If early park advocates had tried to mollify locals to accept park establishment, there would have undoubtedly been logging permitted in the new park. Instead, park supporters successfully rallied people from outside the region to help create the wilderness park we have today.

All legislation is compromise, but don’t be the one to do the compromising—that’s the job of Congress. Make your best case for the best protection. If you don’t achieve that goal in any particular legislation, you can decide to oppose it and attempt to stop it or accept it with compromises. For instance, if you want all the roadless country in a particular area designated as wilderness, propose it all as wilderness and make your best case to save it all. If Congress cuts that in half, you have still successfully made the case that all the roadless lands are qualified for wilderness, and you can always try to enact more protective legislation in the future for these lands. However, if in attempting to secure local support, you automatically say or accept the notion that some of these roadless lands are ecologically unimportant or are throw away lands that can be developed; you have lost your moral authority to fight for protection later.

When and where you compromise affects the outcome, not only current issues but shaped future expectations. Thus a long-term vision should always be kept in mind.

George Wuerthner has published 36 books including Wildfire: A Century of Failed Forest Policy. He serves on the board of the Western Watersheds Project. You can read the original article here.

![Tribal Members Aim to Stop Lithium Nevada Corporation From Digging Up Cultural Sites in Thacker Pass [Dispatches from Thacker Pass]](https://dgrnewsservice.org/wp-content/uploads/sites/18/2021/06/SageGrouse-980x667-1.jpg)