by Deep Green Resistance News Service | Mar 21, 2012 | Climate Change

By Agence France-Presse

Greenhouse gases are likely to result in annual costs of nearly $2 trillion in damage to the oceans by 2100, according to a new Swedish study.

The estimate by the Stockholm Environment Institute is based on the assumption that climate-altering carbon emissions continue their upward spiral without a pause.

Warmer seas will lead to greater acidification and oxygen loss, hitting fisheries and coral reefs, it warns.

Rising sea levels and storms will boost the risk of flood damage, especially around the coastlines of Africa and Asia, it adds.

Projecting forward using a business-as-usual scenario, the Earth’s global temperature will rise by four degrees Celsius (7.2 degrees Fahrenheit) by the end of the century, says the report, “Valuing the Ocean.”

On this basis, the cost in 2050 will be $428 billion annually, or 0.25 percent of global domestic product (GDP).

By 2100, the cost would rise to $1,979 billion, or 0.37 percent of output.

If emissions take a lower track, and warming is limited to 2.2 C (4 F), the cost in 2050 would be $105 billion, or 0.06 percent of worldwide GDP, rising to $612 billion, or 0.11 percent, by 2100.

“This is not a scaremongering forecast,” says the report.

It cautions that these figures do not take into account the bill for small island states swamped by rising seas. Nor do they include the impact of warming on the ocean’s basic processes, such as nutrient recycling, which are essential to life.

“The ocean has always been thought of as the epitome of unconquerable, inexhaustible vastness and variety, but this ‘plenty more fish in the sea’ image may be its worst enemy,” notes the report.

From PhysOrg: http://www.physorg.com/news/2012-03-ocean-climate-trillion.html

by Deep Green Resistance News Service | Mar 12, 2012 | Biodiversity & Habitat Destruction, Climate Change

By Bari Bates

Our oceans face a grim outlook in the coming decades. Ocean acidification, loss of marine biodiversity, climate change, pollution and over-exploitation of resources all point to the urgent need for a new paradigm on caring for the earth’s oceans—”business as usual” is simply not an option anymore, experts say.

The extreme rate of acidification – the term used to describe the decrease in ocean pH levels caused by man-made CO2 emissions – has happened before, Carol Turley of Plymouth Marine Laboratory said, a claim that might have been comforting if she hadn’t been referring to the time when dinosaurs died out.

This is a “huge environmental crisis,” she told attendees at an information session at European Parliament this month, addressing challenges and solutions for the world’s oceans months ahead of the United Nations Conference on Sustainable Development, Rio+20, slated to be held in Brazil in June.

Turley joked that she’s often called the “acid queen” because of her bleak message, though the plight of more than 70 percent of the earth’s surface is not in the least bit humorous.

Each year, the ocean absorbs roughly 26 percent of total CO2 emissions, which have increased by 30 percent since the beginning of the Industrial Revolution in 1750, according to the International Ocean Acidification Reference User Group.

Ocean acidification affects marine life with calcium carbonate skeletons and shells, making them sensitive to even small changes in acidity. Acidification also reduces the availability of calcium for plankton and shelled species, which constitute the base of the entire marine food chain, creating a disastrous domino affect that could wipe out entire ecosystems.

“[The] earth system is truly under the influence of man,” said Wendy Watson-Wright, assistant director general and executive secretary of the Intergovernmental Oceanographic Commission (IOC) of the United Nations Education, Scientific and Cultural Organisation (UNESCO).

The oceans could be 150 percent more acidic by 2100, she added. This means drastic decreases in yields from fisheries, and mass extinction of marine life.

The world is currently losing natural resources at a rate humans haven’t even begun to describe, she said.

Read more from Inter Press Service: http://ipsnews.net/news.asp?idnews=107042

Photo by SGR on Unsplash

by Deep Green Resistance News Service | Feb 28, 2012 | Mining & Drilling, Toxification

By Ecowatch

Each year, mining companies dump more than 180 million tonnes of hazardous mine waste into rivers, lakes, and oceans worldwide, threatening vital bodies of water with toxic heavy metals and other chemicals poisonous to humans and wildlife, according to report released on Feb. 28 by two leading mining reform groups.

An investigation by Earthworks and MiningWatch Canada identifies the world’s waters that are suffering the greatest harm or at greatest risk from the dumping of mine waste. The report, Troubled Waters: How Mine Waste Dumping is Poisoning our Oceans, Rivers, and Lakes, also names the leading companies that continue to use this irresponsible method of disposal.

Mine processing wastes, or tailings, can contain as many as three dozen dangerous chemicals including arsenic, lead, mercury, and cyanide. The report found that the mining industry has left mountains of such waste from Alaska and Canada to Norway and Southeast Asia.

“Polluting the world’s waters with mine tailings is unconscionable, and damage it causes is largely irreversible,” said Payal Sampat, international program director for Washington, D.C.-based Earthworks. “Mining companies must stop using our oceans, rivers, and lakes as dumping grounds for their toxic waste.”

The report says some multinational mining companies are guilty of a double standard.

“Some companies dump their mining wastes into the oceans of other countries, even though their home countries have bans or restrictions against it,” said Catherine Coumans, research coordinator for Ottawa-based MiningWatch Canada. “We found that of the world’s largest mining companies, only one has policies against dumping in rivers and oceans, and none against dumping in lakes.”

There are safer methods of disposing of mine tailings, including returning the waste to the emptied mine. In other places, dumping of any kind is too risky. No feasible technology exists to remove and treat mine tailings from oceans; even partial cleanup of tailings dumped into rivers or lakes is prohibitively expensive.

“We are really suffering because of the millions of tons of mine waste that Barrick Gold dumps in and around our river system every year,” said Mark Ekepa, chairman of the Porgera Landowners’ Association. “Our rivers run red, our houses have become unstable, we have lost fresh drinking water and places to put our food gardens, and sometimes children get carried away by the waste.”

A number of nations, including the U.S., Canada, and Australia, have had restrictions on dumping mine tailings in natural bodies of water. Even these national regulations, however, are being eroded by amendments, exemptions, and loopholes that allow destructive dumping in lakes and streams. Even though U.S. law long banned lake dumping, in 2009 the U.S. Supreme Court allowed Coeur D’Alene Mines of Idaho to dump 7 million tonnes of tailings from the Kensington Gold Mine in Alaska into Lower Slate Lake, filling the lake and destroying all life in it.

In Canada, Taseko Mines Ltd. is proposing to reclassify Little Fish Lake and Fish Creek in British Columbia as a tailings impoundment for its proposed Prosperity Gold-Copper Mine. The watershed is home to grizzly bear and highly productive rainbow trout, and is an important cultural area for the Tsilhqot’in People. After being refused environmental approvals for the past 17 years, the company has re-applied with plans to build a tailings impoundment to dispose of 480 million tons of tailings and 240 million tons of waste rock in the basin of the creek and lake, burying the ecosystems under a hundred meters of waste.

From Ecowatch

Photo by Dominik Vanyi on Unsplash

by Deep Green Resistance News Service | Feb 22, 2012 | Biodiversity & Habitat Destruction, Climate Change

By Katharine Gammon

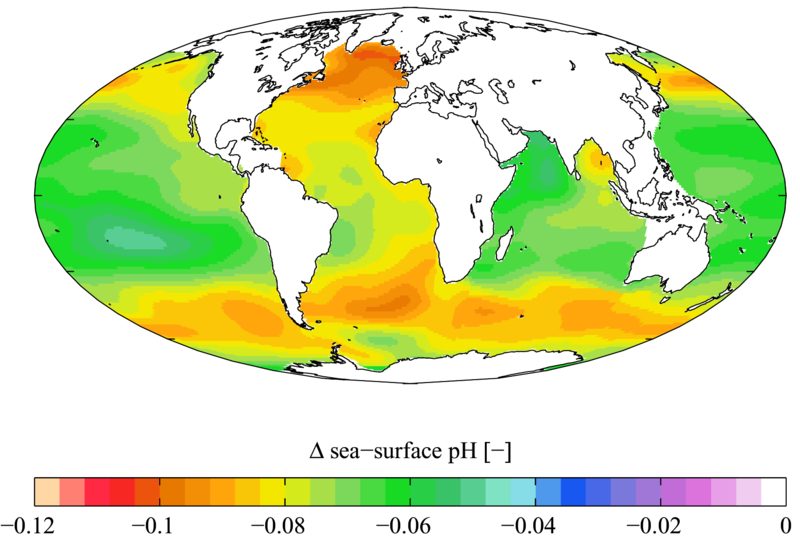

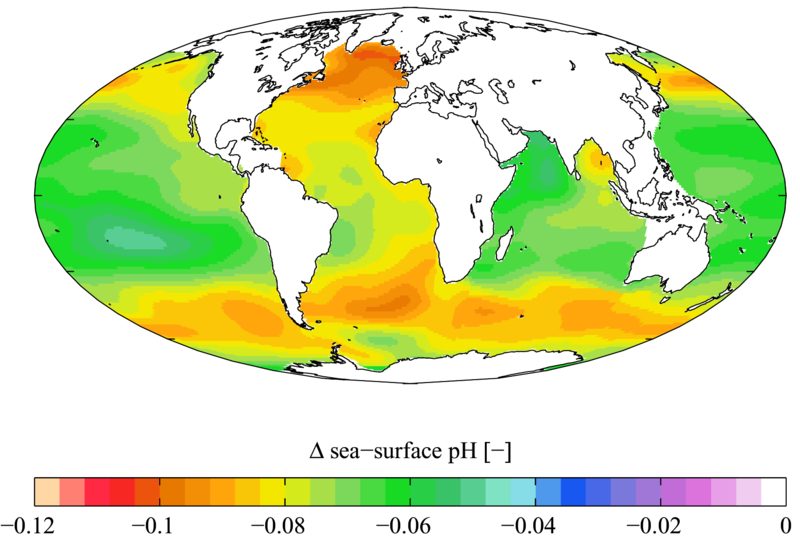

The oceans have already absorbed about one-third of the 500 billion tons of carbon dioxide that human activity has added to the atmosphere since the industrial revolution. Absorbing carbon dioxide reduces the pH of seawater, indicating an increase in its acidity.

While more attention has been focused on the ecological fragility of coral reefs, cold-water life in other regions — from urchins and sea-stars to tiny plankton-like copepods — may be more at risk than their warmer-water counterparts, according to information presented at the American Association for the Advancement of Science annual meeting in Vancouver.

Like many effects of climate change, the impacts of acidification can vary from place to place.

“Ocean warming-related issues that have economic punch will not be evenly spread around the globe,” said Gretchen Hofmann , a professor of marine biology at the University of California, Santa Barbara. “They will be local, focal, and intense.”

The physical mechanisms are clear: because cold water tends to hold more gas, the Arctic and Antarctic oceans already contain more carbon dioxide than other areas. In a world with oceans even more acidic than they are today, marine creatures that form shells or body structure from calcium carbonate may struggle to create their structures. Losing those species will negatively affect species that are higher up on the food chain, like herring.

Already, some oyster hatcheries in the Pacific Northwest recently failed to produce oysters because the water had become too acidic for the larvae to form shells, Hofmann said.

Scientists are just beginning to predict what will happen in the future with more acidic waters. Jason Hall-Spencer, of Plymouth University in the U.K., studies life at sites where natural carbon dioxide bubbles like a Jacuzzi from the ocean floor. He chooses places along the carbon-rich sea floor vents that mimic the effects of high acidity in the rest of the ocean’s future — a time machine for looking at hundreds of species in conditions that will exist 10 or 50 years down the road.

Hall-Spencer has studied volcanic vents in Italy, California and Papua New Guinea. All of them show similar effects. “What we see are dramatic shifts in ecosystems, with a tipping point predicted at end of this century,” he said. That tipping point would spell out a 30% drop in biodiversity in everything from corals to fish, he added.

Hall-Spencer said that some organisms strain attempt to keep up with changing conditions. “It’s like us panting for oxygen at high altitude – they’re struggling,” he said.

Hall-Spencer called the combination of warming and acidification “a deadly noxious cocktail.” He said that worst-case scenarios predict that acidity will increase another 150 percent by 2050 — and warming and acidification are a double-whammy.

From Physorg: http://www.physorg.com/news/2012-02-world-oceans-acid.html

by DGR News Service | Apr 19, 2025 | ACTION, The Problem: Civilization

A Wild Earth Day!

On April 22:

Meet free-roaming bison and baby prairie dogs! Learn about oceans that need us and fires that don’t! Take a fast trip through human history, from cave art to the current mess! Get inspired by tales of resistance and songs of love! All donations go directly to help fund our annual conference.

And you can double your impact by giving during A Wild Earth Day!

A dedicated activist has offered to sponsor this year’s conference through her small business in Philadelphia. Richter Renovations will match gifts during the Earth Day fundraiser, up to $2000.

So get your biophilia on and mark your calendars! 6PM PST/9PM EST.

DGR CONFERENCE!

The annual conference will be in Philadelphia this year, August 1-5. Derrick and I will both be there. The conference is always a weekend of radical fun and friendship so let your enthusiasm build!

Click here for full information.

USA TOUR!

And we could really use your help. Since we are going to be traveling across the country, we want to make a whole tour of it. If you want to host us for a talk, we’ll go anywhere.

We’re calling it the “Don’t Cancel Me Tour.” The t-shirts will be easy; the events will take some courage. But we believe in you. I never guessed saving the planet would start with facing down the Cancel Mob, but here we are. Drop us a note (contact@deepgreenresistance.org) if you want to help.

STORE!

Our website is undergoing a massive overhaul. A new section is now complete–the DGR store! We have beautifully designed t-shirts and hoodies in a rainbow of colors, all of them declaring loving loyalty to the living planet. Check it out here.

HELP!

We can’t do any of this without your generous donations. We want to say thank you with some awesome premiums.

If you donate $100, you get some free books. For a $200 donation, you get books and the t-shirt of your choice. For a $500 donation, you get all the above and a batch of (in)famous gluten-free brownies. For a $1000 donation, all of that plus a private Zoom call with Derrick and the bears.

So check out our merch, put on your courage, and no matter what: find what you love, defend your beloved.

Stay strong!

Lierre (and Derrick and Deanna)

PLEASE DONATE

Deep Green Resistance Inc

PO Box 903

Crescent City, CA 95531-8002

Banner Photo by Shamblen Studios on Unsplash