by DGR Colorado Plateau | Nov 21, 2015 | Indigenous Autonomy

INDIGENOUS CUSTODIANS CALL FOR RECOGNITION AND PROTECTION OF SACRED NATURAL SITES

Indigenous custodians from Benin, Uganda, Kenya and Ethiopia have released a powerful new statement outlining the importance of sacred natural sites and governance systems.

Emerging out of a biocultural diversity revival movement that’s starting to build serious momentum across continental Africa, the statement forms the heart of a new report that builds the case for the African Commission on Human and Peoples’ Rights to do its part.

The new report, authored by The Gaia Foundation, African Biodiversity Network and human rights lawyer Roger Chennels, draws attention to the way that sacred natural sites and their community custodians have been systematically undermined and violated since the colonial era. Despite the official decolonization of Africa, this persecution continues today, say the authors, who have extensively documented the renewed scramble for Africa’s land, mineral, metal and fossil fuel wealth and its impact on Indigenous territories.

Sabella Kaguna, a sacred site custodian from Tharaka, Kenya, with a map of her ancestral territory and indigenous seeds (Photo: The Gaia Foundation)

Both the custodians and the report’s authors are now urging the African Commission to invoke the African Charter on Human and People’s Rights (African Charter). and protect sacred sites, governance systems and custodians in a ‘decisive policy and legislative response’ to these threats.

SACRED NATURAL SITES

SOURCE OF KNOWLEDGE, CULTURE AND LAW

According to the new report, sacred sites are “Places of ecological, cultural and spiritual importance, embedded in ancestral lands”. They also play an important role in community conflict resolution practices and other traditions central to the cultural life of Indigenous Peoples.In their statement custodians describe the centrality of sacred sites to their existence, writing that “Sacred natural sites are where we come from, the heart of life. They are our roots and our inspiration. We cannot live without our sacred natural sites, and we are responsible for protecting them.”

Sacred site custodians from Bale Ethiopia. (Photo :Tamara Korur)

The custodians go on to outline in detail how sacred natural sites are the primary source of their laws and customary governance systems. Drawing together a list of common customary laws, the custodians demonstrate how these governance systems enable Indigenous Peoples to both protect their territories and maintain their ways of life and identities.

Quoting Beninese custodian Ousso Lio Appolinaire on the relationship between nature and culture, the report’s authors emphasize that a priori laws based upon and derived from the laws of the Earth underpin the great diversity of laws and customs practiced by Indigenous Peoples worldwide.

“In the beginning there was Nature; culture and indigenous knowledge come from Nature. Nature cannot be protected in a sustainable way without the culture of that place. The erosion of culture leads to the destruction of Nature. It is critical to conserve the culture and knowledge of our ancestors for good ecological governance in service of Nature”, says Appolinaire.

The custodians’ are calling for the African Commission to recognize and protect sacred natural sites on the basis that they are the foundations of the governance systems, cultures and values celebrated and enshrined in the African Charter.

The report discusses at length the commitment the African Charter makes to recognizing Africa’s legal plurality, including Indigenous People’s customary governance systems. Laying out a broad vision for an Africa free of colonialism, Articles 17, 18 and 61 of the Charter promote plurality and the traditional cultural values that, for custodian communities, are intimately tied to the existence and health of sacred natural sites.

In order to safeguard these rights, sacred natural sites must be protected, and the customary governance systems connected to them honored, argues the report.

LOSING LAND AND MEMORY

SACRED SITES UNDER THREAT

The custodian’s statement intimates a critical need to protect sacred natural sites in accordance with the African Charter due to the interconnected crises of disappearing knowledge and increasingly devastated ecosystems.

VhaVenda community members and their ecological calendar in Venda Limpopo. (Photo: Will Baxter)

“We are deeply concerned about our Earth because she is suffering from increasing destruction despite all the discussions, international meetings, facts and figures and warning signs from Earth… the future of our children and the children of all the species of Earth are threatened. When this last generation of elders dies, we will lose the memory of how to live respectfully on the planet, if we do not learn from them now,” say the custodians.

As remedy, the custodians describe a litany of destructive and disrespectful practices that sacred natural sites ought to be legally protected from. These include unwanted tourism, research and documentation, the use of non-indigenous seeds, land grabbing and financial speculation.

Special attention is given to the problem of extractivism, with custodians declaring sacred natural sites to be ‘No Go Areas’ for mining and other forms of destructive ‘development’. They write that “Sacred natural sites are not for making money. Our children need a healthy planet with clean air, water and food from healthy soils. They cannot eat money as food or breathe money or drink money. If there is no water, there is no life.”

“In my country sacred sites are holy places, they are not a place for infrastructural development. Those sites are kept by the community”, says Sabella Kaguna, a custodian from Tharaka in Kenya and one of the statement’s authors.

In order to ensure custodian communities are empowered to protect sacred sites on their own terms, the custodians are seeking legal parity. They write that they have observed how the dominant legal system in their home nations is operationalized to legitimize the destruction of sacred natural sites in contravention of their own laws and customs.

This trend has been recognized by the African Commission’s own Working Group of Experts on Indigenous Populations. In a 2010 report the group described how “Indigenous communities in Kenya, like most others in Africa, often rely on their African customary law. However, Kenya’s legal framework subjugates African customary law to written laws. […] African customary law is placed at the bottom of the applicable laws”.

The report draws attention to examples of ‘multi-juridicial’ legal systems from around the world as examples of how indigenous legal traditions can be given greater parity. Describing the African Charter as ‘replete’ with references with legal pluralism and the need to respect ancestral legal systems, it makes the case for more wide-ranging and robust protection of these systems in African nations under the Charter.

A REVIVAL GATHERS PACE

Though the custodians’ statement calls for new actions from the African Commission and member states, at the grassroots level Indigenous custodian communities have been taking active steps to protect sacred natural sites for a number of years.

The report shares a number of case studies that showcase the success Indigenous communities have had in protecting sacred sites so far.

Meeting of sacred site custodians at Lake Langano, Ethiopia 2015 (Photo: The Gaia Foundation)

Benin is home to a network of sacred natural sites, known as Vodun zun, including over 2,940 sacred forests. In 2012, due in large part to the work of Indigenous-led organization GRABE-Benin, Benin set a new precedent by creating a ‘sacred forest law’ (Interministerial Order No.0121). The law formally protects sacred forests, recognizing their importance for biodiversity and ethno-cultural traditions.

Since that time GRABE-Benin has accompanied communities to apply for registration and legal recognition of their sacred forests as protected areas, as well as recognition of the communities’ rights to govern and protect them. By the end of 2013, a total of nine sacred forests had been formally protected.

Sheka Forest (Photo: Will Baxter)

In the Sheka region of Southern Ethiopia, a region famous for rare afromontane forests, Shekacho communities have made great strides to protect the area’s 200+ sacred natural sites from threats such as deforestation.

With assistance from MELCA-Ethiopia, a local NGO, the communities have begun to revitalize their traditional culture, and clans have united to seek protection for sacred sites. As a result of these efforts, Sheka Forest was recognized as a UNESCO Biosphere Reserve in 2012. Since then, the regional government has issued a regulation for the protection of the Sheka forest Biosphere Reserve.

These successes are part of a wider process of Indigenous cultural revival under way across Africa. The report describes how communities such as those in Sheka and Benin are coming together to rebuild their cultural identities and customary governance systems. In doing so, they are challenging dominant legal systems that continue in the colonial vein of legitimizing eco-cultural destruction, rather than preventing it.

A new film from the report’s authors provides greater insight into this ongoing revival. In the film, Method Gundidza of the Mupo Foundation (South Africa) describes the critical importance of customary governance at a time of multiple eco-social crises:

“We are saying that law should derive from nature. And if law should derive from nature, customary governance systems are the law. This is where it (law) should come from. These are the (Indigenous) people whose day-to-day lives reflect how to live with nature and how to care for nature.”

The custodians and their supporters now hope their statement will impress this key insight upon the African Commission and inspire them to action. In the meantime, they will continue with their quiet revolution.

by DGR Colorado Plateau | Sep 18, 2015 | Indigenous Autonomy

By Robin Llewellyn / Intercontinental Cry

Children of the Wounaan People easily find diversion in the abandoned basketball stadium of Buenaventura, the largest city on Colombia’s Pacific coast. Some chase pigeons that try to settle around the highest rows of seats, casually resting to look out over the surrounding rooftops to the islands of mangrove and forest that bar the view to the sea. Others jump skipping ropes as two siblings ride brightly-coloured toy ponies past the plastic sheeting beneath the bleachers that grant each family their privacy.

Displacement from their territory has exacted a cruel cost. Two children have died since their community of Unión Aguas Claras was forced to flee ten months ago: one year-old Neiber Cárdenas Pirza died while suffering diarrhoea and vomiting last December, then in June the community lost a two day-old baby.

According to one of the displaced Wounaan it is “all the chemicals” in their new life that are to blame, coupled with the inadequate diet provided by Colombian authorities that leave them vulnerable to sickness. The concrete structure of the basketball stadium is also less hygienic than the wooden homes in the territory they were forced to abandon, she said.

But to another Wounaan there lies a deeper cause:

It is not just the illnesses of the Occident that have made us so ill. It is because of spiritual sickness; because of the loss of our spirituality.

He claimed that the deadly sickness in June was foreseen by their shaman, who had been unable to predict whether it would kill an adult or a child.

The community was preparing for a ceremony the following day in which they would use their spirits to “see” how affairs stood in their territory that has lain abandoned for nine months.

The pressures against them had been manifesting for years, the Wounaan told IC, through the armed conflict, petrol exploration, and narco-trafficking.

“The area is very strategic: the river marks the frontier of the FARC and the paramilitaries, and is also the means by which the Army moves,” One Wounaan explained. “Now all of the Rio San Juan has become militarized.”

In 2008 there was a massacre of six indigenous people in our territory. By 2014 we realized that we couldn’t resist any longer; we couldn’t move in our territory for all the armed groups passing through, we had to stay in our houses.

By November 2014, the harassment was no longer confined to their wider territory. A Wounaan woman explained that, one day, “Six paramilitaries arrived and asked to sleep in the settlement but the community replied that they could not; we said that we reserve the right to say no to all armed groups.”

That evening the local head of the paramilitaries arrived to threaten the assembled community, warning them that their attitude could only work to turn over their territory to other armed groups. Fearful for their safety, the people of Unión Aguas Claras resolved to leave together. A total of 344 people–63 families–boarded boats before dawn and descended the San Juan River to where it joins the lower Calima River. From there, they reached the estuary and followed the coast to Buenaventura, where Colombian authorities placed them in a stadium that only recently became vacant. Shortly before the Wounaan’s arrival, it sheltered Afro-Colombian and campesino families displaced by clashes in Bajo Calima between the Armed Forces and BACRIM (“bandas criminales” – armed criminal bands mostly born out of officially disbanded right-wing paramilitary groups).

Not a single person from the community stayed back. Describing how the community fished and grew “yucca, bananas, pineapples… everything”, one Wounaan lamented, “Now there will be nothing left of our farms; back there in our territory everything will be destroyed.”

When they were in their territory, all the women would gather every two months to prepare and weave threads extracted from the Werregue Palm into baskets and handicrafts that they would sell. The community would hold meetings to arrange days of minga, collective communal work that could involve tidying the territory or arranging the sewing of seeds in their farms. They also said that they carefully guarded their culture, one person stating unequivocally that, “He who does not speak Wounaan is not a Wounaan.”

The Wounaan language is now spoken in many of Colombia’s biggest cities, including Bogota, Medellin and Cali, where many Wounaan end up after being cleared from their homelands in the Pacific regions of the Valle del Cauca and Choco departments. Throughout 2014, Colombia’s National Victims’ Unit recorded 97,453 cases of forced displacement, with the Pacific region among the most impacted.

Wellington Carneiro of Buenaventura’s UNHCR office says there have been “several displacements of indigenous Wounaan communities [including] Balsalito, Chachajo, Chamapuro, Buenavista, Tio Cirilio, and Agua Clara, and recently the Papayo community. In total more than 1000 people have been displaced from the Lower San Juan River.”

The identity of the groups fighting for control of the San Juan and Calima waterways is unclear. The local authorities in Buenaventura initially responded to the community’s arrival by claiming there had been no need for the Wounaan’s displacement, and their territory was safe for their return.

However, according to Carneiro,

The Lower San Juan river is strategic to armed groups due to the access to the sea and for the trafficking of weapons and drugs. Also, with the tighter security implemented around the port of Buenaventura, the routes through the San Juan delta became more attractive. There are several groups disputing the control of the area apart from the Colombian Navy. This…puts the population under the pressure of armed groups for information and through restrictions to their mobility and other threats in the context of a disputed military control over the area.

Colombia has been wracked by a conflict between two competing drug-trafficking networks – the rising Urabeños and the declining Rastrojos – who each seek to monopolize the transport of cocaine via the Pacific coast. Confronted by a stubborn Rastrojos presence in Cali and Buenaventura, the Calima and San Juan rivers have become more strategic as the San Juan is fed by the Capomá river that provides a route into the Colombian interior.

The area has also seen BACRIM and guerrilla groups diversify their enterprises through illegal mining, timber, and agriculture. According to one of the displaced Wounaan, such activities of illegal armed groups are only one aspect of a broader war against indigenous territories across Colombia. He also warned that this broader conflict will not cease with the possible signing of a peace accord between the government and FARC guerrillas.

We will continue to face war. It may be a war without lead against the indigenous – a psychological war, a cultural war, or possibly also a physical war… We know that the peace process will open the way for megaprojects that will bring international investments into our territory, therefore we know that true peace will not come. For indigenous peoples the violence will not end with the peace process. The peace process will not resolve anything for us.

The peace negotiations have been proceeding in Havana, Cuba, despite the intense opposition of former president Alvaro Uribe and his powerful Centro Democratico party. An agreement is expected to be announced in the coming months, to be followed by a reworking of the country’s 1991 Constitution.

Another Wounaan commented,

Uribe has proposed that constitutional reform should proceed and constitutional reform will likely follow a peace accord. Indigenous people are totally unprepared and un-mobilized to participate in the process of rewriting the Constitution: we need to organize ourselves to shape this process.

The aims of the Centro Democratico are clear in the Septima Dia broadcasts of Caracol, which are so aggressive against indigenous people, because Centro Democratico wants to exterminate the indigenous movement.

Earlier this year, Caracol, one of Colombia’s leading private TV channels, broadcast a series under its Septima Dia weekly format on Colombia’s Indigenous Peoples, called Disharmonization: the Arrow of the Conflict. The controversial series attacked indigenous justice systems and claimed that indigenous authorities took massacre compensation from their intended recipients, an allegation that was debunked. The series also insinuated that indigenous institutions were supportive of FARC guerrillas, something that Colombian journalist Cesar Gaviria described as but one falsehood in a series “plagued by investigative and journalistic failures”.

Indigenous Nasa activists seeking to recover the La Emperatriz sugar plantation “from its rightful owners” were among those targeted by the series which also served as a platform for Centro Democratico’s Paloma Valencia, who advocates dividing the department of Cauca into two: “One for the indigenous for them to do their strikes, their demonstrations, and their invasions. And one directed towards development where we can have roads, promote investment and where there are dignified jobs for the Caucanos.”

Henry Caballero Fula of the Peace Commission of the Regional Indigenous Council of Cauca (CRIC) has written that the four aims of the Septima Dia broadcasts were to spread the views that:

Indigenous autonomy is something negative; it only helps to corruptly enrich some members, while harming the community in general and the non-indigenous sectors.

It was a mistake for the right to prior consultation to be integrated into the Colombian Constitution since it harms national development.

The indigenous justice system is another mistake in the Colombian Constitution: it is applied against the community and is the base of impunity and immunity for indigenous criminals.

Indigenous people receive many benefits and these are generating breakdown and corruption.

The trajectory of such arguments in Colombia’s current political climate are a pressing danger to Indigenous Peoples, according to the displaced Wounaan who are politically active through the Regional Indigenous Organization of Valle del Cauca (ORIVAC).

On Sept. 15, Feliciano Valencia of Cauca’s Nasa people, one of the most visible indigenous leaders in Colombia, who had addressed delegates of the displaced Wounaan at an ORIVAC conference, was abruptly arrested and imprisoned on charges that were previously dismissed in 2011. The charges stemmed from a 2008 controversy in which an undercover soldier–who had been exposed infiltrating a peaceful protest–was held subject to indigenous justice mechanisms. The CRIC argues that indigenous jurisdiction forms part of the 1991 Constitution, and that the imprisonment of Valencia is a “coup by the state against our Constitutional rights, and revokes the peace treaty that the Constitution of ’91 represents in our history.”

These developments hadn’t yet occurred when IC spoke to the Wounaan in Buenaventura, however, one person concluded that “Indigenous people face an emergency situation throughout the country, not just in the Rio San Juan.”

The Wounaan are now changing their strategy over how to return to their territory, turning away from the municipal and departmental authorities and towards the Ministry of the Interior, the Ombudsman, and the international community.

The municipal authorities are not cooperating with the indigenous people; they always tell lies – they always say they will do something ‘mañana.’ We present our willingness to return but we need guarantees of security and dignity in our territory. Because the local level has not achieved anything we go to the national and international level, including to NGOs and the UN.

The UNHCR’s Wellington Carneiro cautions that the government ministries in Bogota lack a presence in the region and don’t have “a clear picture on the problems of the Wounaan,” however, “there is also a very negative stigmatization of the indigenous communities by the local authorities.”

Photo: Robin Llewellyn

One of the Wounaan observed that local officials “always come and talk, and then afterwards [do] nothing.” She said that her emphasis was on maintaining and developing the cultural and political activities of the group: “We need to strengthen our community so we can defend our territory”.

by Deep Green Resistance News Service | Jun 22, 2015 | Direct Action, Strategy & Analysis

By Will Falk / Deep Green Resistance

I went up to Mauna Kea’s summit a few days ago to pule (to pray) with some of the protectors on a ridge inside the Thirty Meter Telescope’s (TMT) proposed construction site. When we reached the site, we were confronted by half a dozen large men in orange vests and hard hats brandishing cameras, audio recorders, and notebooks.

The boss told us we were trespassing on an active construction site and subject to arrest. I looked around and saw nothing but a handful of back-hoes, the open sky at 14,000 feet above sea level, and a sublime, obsidian-colored cinder field stretching to the clouds. Of course, as I’m writing this, construction on Mauna Kea has been suspended for more than two months.

Kaho’okahi Kanuha explained that we were simply here to say some prayers. The boss told us again we were subject to arrest, mumbled into a hand-held radio, signaled to his men, and began recording us with a camera. The six men took up positions surrounding us as we held hands and faced the sky with Kaho’okahi leading some chants. Some of the men folded large arms across their chests glaring at us, others recorded us on camera, and one circled us nervously. I’ve been in a few fist fights in my life – needless, pointless expressions of a toxic masculinity – and I felt like these men were revving themselves up for some sort of scrap.

It was impossible for me to pray like this. Kaho’okahi seemed completely unnerved and when I asked him about it, he said this happens every time he comes to pray. I remember my experiences in Mass when I was younger. I imagine a priest at the altar leading his parish in the prayers that, for Catholics, turn bread and wine into the body and blood of Christ – all while strong men in hard hats patrol the pews and record the liturgy.

This, of course, would never happen. So, I ask: When Kanaka Maoli pray on a mountain exceedingly more beautiful than any basilica or cathedral I’ve ever been in, why are they being harassed like this?

I spent the first six essays in this Protecting Mauna Kea series trying to answer this question. The answers I came up with are validated after spending the last two weeks up here. The TMT project is based on the dominant culture’s sense of entitlement, historical amnesia, and pornification of Hawaiian culture. What could resemble a porn shoot more closely than men with cameras intruding on and recording acts of intimacy?

I think I’ve demonstrated that the TMT project is enabled by a problematic worldview and should not be allowed to proceed. After Governor David Ige’s announcement last week that he would support and enforce the TMT’s construction, the Mauna Kea protectors want the world to know we never expected the State to help us. We must stop the TMT project and we must do it ourselves. The question becomes: “How do we do it?”

The occupation on Mauna Kea is an expression that the protection of Mauna Kea is the people’s responsibility. We cannot trust the government to stop the TMT. We cannot trust the police. We cannot trust the courts. We have to do it ourselves. In other words, nothing has changed since the occupation began over two months ago. In many ways, the occupation on Mauna Kea reflects all of our environmental and social justice movements around the world.

The truth is – on the whole – environmental and social justice movements around the world have been getting their asses kicked. If they weren’t, 200 species a day wouldn’t be going extinct around the world. If they weren’t, we wouldn’t be losing indigenous languages at a rate relatively faster than species. If they weren’t, 95% of North America’s old growth forests wouldn’t have been clear cut. If they weren’t, every mother around the world wouldn’t have dioxin – a known carcinogen – in her breast milk. And, why are they getting our asses kicked? One reason is we’ve trusted those in power to do the right thing for far too long. The good news is – while construction on the Mountain is suspended – we have the opportunity to avoid mistakes other movements have made.

**********************

A couple days ago in a freezing cold, clinging mist, the Mauna Kea protectors called a 5:30 AM meeting in the now-famous crosswalk on the Mauna Kea Access Road to talk strategy in light of Governor Ige’s recent announcement. Some protectors lamented the announcement and were understandably scared about what was coming next. Others maintained that the TMT project was illegal anyway, and the courts would never let it proceed. Still others cited Kingdom of Hawai’i precedents and referred to the recent war crime charges filed with the Canadian government, to assure us the TMT was dead in the water. Finally. the boldest proudly proclaimed – with a hint of the false bravado that often accompanies anxious realizations – construction equipment would have to roll over their dead bodies to get to the construction site.

I stood silently in the circle listening. I am not Hawaiian and have no place arguing with those whose land I presently occupy. My mind was filling with memories of my experiences as a public defender. I recalled the cop in Kenosha, WI where I worked who put a gun to the temple of young Michael Bell’s head and murdered him as his mother and sister watched on for the crime of possibly breaking his bail conditions. I recalled that the cop was promoted and still on the force in Kenosha.

My stomach began churning as I felt that old feeling of helplessness sitting in a wooden chair in a courtroom next to another client being sentenced to prison while there wasn’t a damn thing I could do about it. There was no brilliant legal argument I could make, no impassioned plea the judge would listen to. The judge had power and armed men at his command, and I did not. It was as simple as that.

My heart was tugged back to Turtle Island, the so-called North American continent where the arrival of Europeans has meant the total extermination of dozens of aboriginal peoples. I think of the Taino who were annihilated within a few decades after Columbus’ contact with them. I can almost hear Tecumseh’s voice calling out from now-dead villages in present-day Ohio and Indiana asking what happened to the Pequods, the Narragansetts, and the Pocanokets. These peoples were wiped out by European colonizers while most of Tecumseh’s people, the Shawnee, were removed at gunpoint from their homelands in the Ohio valley hundreds of miles away to Oklahoma.

Some of the protectors here tease me, calling me “America’s ambassador to Hawai’i.” Listening to some of the protectors insist that the courts, the police, and the government would never let the TMT project happen, I wanted to explain that I understand the dominant culture we’re fighting against. I wanted to say I benefit from this culture. I was raised within in. I’ve lived amongst the type of people who run those courts, sit in their government, and become the police. I know what they are capable of and that many of them are sociopaths with no regard for the well-being of those who oppose them.

I didn’t say this, though, because I knew these feelings brought me too close to acting like the White Savior come to save aboriginal peoples from their ignorance. The truth is Kanaka Maoli understand very well – much better than I – the genocidal tendencies of the dominant culture occupying their lands. They do not need my reminder. I write about this now, only to narrate my relief when Kaho’okahi said, “I understand everyone’s concerns, but the way we’re going to win this struggle is pule plus action.”

**********************

Pule plus action. I agree with Kaho’okahi. Protecting Mauna Kea requires a strong spirituality, requires prayers, but it also means real, physical actions in the real, physical world. We need prayers, yes, just like we need those battling the TMT project in the courts, just like we need those signing petitions against the TMT project, just like we need those donating to the Mauna Kea protectors’ bail fund. But, at the end of the day, the surest way to stop the TMT project is to physically, actually stop the TMT project. This is what the encampment on Mauna Kea has always been about. The protectors are determined to place their bodies in between Mauna Kea’s summit and the construction equipment escorted by the police that will soon come to build the telescope.

I hope with all my heart that the courts will make the right decision and prohibit the TMT’s construction. I hope with all my heart that when the police receive their orders to pacify resistance on the Mountain that they will turn in their resignation papers. But, I’m not holding my breath. History has shown over and over again that the courts and the police will not help us.

Hope is not going to keep the destruction off Mauna Kea. It is much more likely that hope will bind us to ineffective strategies like trusting the government and hugging the police when they come to arrest us.

The Mauna Kea protectors insist on observing kapu aloha – a practice of love and respect – on the Mountain. I will not question this practice, but I will point out that our opponents do not observe kapu aloha. I fear that the more effective we become at stopping their project, the more violently they will respond.

I do not write this from a place of despair. I write this to give a clear-eyed vision of the effort it’s going to take. If we’re going to keep the TMT project from completion, we are going to have to do it ourselves. We’re going to have to show up in numbers large enough to overwhelm the police. We’re going to have to produce a mass of humanity thick enough to clog the Mauna Kea Access Road – and we may have to do it day in and day out for weeks. It will take a tremendous amount of bravery, shrewd strategic thinking, and a deep commitment from all of us. Or, in Kaho’okahi’s words, it’s going to take pule plus action. This is nothing new, though, and I believe we will win.

by Deep Green Resistance News Service | May 5, 2015 | Indigenous Autonomy

By Will Falk / Deep Green Resistance

When people have asked me why I am going to Hawai’i to help protect Mauna Kea and my answer involves words like “sacredness” or “spiritual,” I am surprised whenever I see the grimaces.

I often get an explanation like this, “I support indigenous people, of course, but the telescope is for science. Isn’t it a little…superstitious to block an astronomy project for a mountain?” I said I was surprised, but I shouldn’t be. Spirituality, I forgot, is anathema in many leftist circles.

It shouldn’t be.

I understand that many in this culture have been wounded by their experiences with religion. Some religions have, on the whole, been disasters for the living world. But, to write off all spirituality because of the actions of a few religions, is not just intellectually lazy and historically inaccurate, it erases the majority of human cultures that lived as true members acting in mutual relationship with their natural communities.

I am writing this article from occupied Ohlone territory in what is now called San Ramon, CA (in the Bay Area). According to the first European explorers who arrived here, this place was a paradise.

A French sea captain, la Perouse, wrote, for example, “There is not any country in the world which more abounds in fish and game of every description.” Flocks of geese, ducks, and other seabirds were so numerous that a gun shot would cause the birds to rise, “in a dense cloud with noise like that of a hurricane.”

In 250 years, with the arrival of Europeans and their spiritualities, we have gone from flocks of birds making noises like a hurricane to the concrete jungles many of us call “home.”

What was it about the Ohlone people that caused them to live in such balance with their natural community? Why didn’t the Ohlone people exhaust their land bases, over shoot the carrying capacity of their home, and colonize other lands like the Europeans who came with their crosses held high forcing the Ohlone to work and to die in the Missions? Only a racist could say, “Because they weren’t smart enough.”

Let me suggest that it was the Ohlone spirituality, the Ohlone way of relating to the world, that caused them to live the way they did. Of course, the Ohlone are just one of thousands of indigenous examples.

Right now, with the world on the verge of total collapse, wouldn’t we do well to respect the wisdoms developed by indigenous peoples who lived in balance with their land bases for thousands of years?

***

Those attempting to force the TMT project on Mauna Kea are products of a culture that has committed spiritual suicide. The dominant culture committed spiritual suicide when it adopted the belief that the land – as the physical source of all life – is not sacred.

Now, it attempts real suicide. I know because I did it, too. Twice.

The path to suicide begins with lies – lies like the notion that a mountain like Mauna Kea does not and cannot speak. As Derrick Jensen points out in A Language Older Than Words, the first thing they do in vivisection labs is cut the vocal cords of the animals they’re going to torture so they don’t have to hear the animals’ screams.

Now the dominant culture is cutting the vocal cords of the entire planet. Women are objectified so they may be raped, indigenous peoples are called savages so they may be massacred, and mountains are described as piles of matter so their tops may be chopped off, their guts ripped out in open pit mines, and massive telescopes built on their peaks.

The Sioux lawyer and author, Vine Deloria Jr., in his work God is Red, diagnosed our current environmental disaster as essentially a spiritual failure.

For Deloria, the Western notion that spirituality can be transported across space, time, and cultural context is a lie and leads to the spiritual emptiness that European settlers on this continent display.

Even worse, though, dominant Western spiritualities like Christianity demand that believers place their faith in a God existing somehow above and beyond the real, physical world. Instead of a belief in the land as the source of all life, an abstract, jealous, invisible, and largely incomprehensible male deity becomes the source of all life.

A hierarchy of beings is established with God on top, followed by angels, humans, animals comparable to humans evolutionarily, all the way down to plants, insect, and microbes. Mountains like Mauna Kea, in this view, are simple heaps of dirt. They may be pretty to look at, but nothing more.

My personal path to suicide reflects the cultural path to suicide Jensen and Deloria describe.

My family is devoutly Catholic. Before I turned 18 and left home, I can count the number of times I missed Mass on one hand. One of my grandmother’s favorite Christmas gifts was handmade, specially blessed rosaries. She says the rosary every morning. Scapulars hang from the rearview mirrors of cars family members drive. Of course, every doorway contains artistic renditions of Christ’s crucifixion.

I remember sometime in my early teens standing beneath a particularly brutal crucifix when I recognized the spiritual emptiness surrounding me. I looked at the crown of thorns piercing Christ’s forehead. I watched the blood running into his eyes. I winced at the spikes driven through his hands and feet. I knew that Christ’s femurs were broken by soldiers – mercifully, perhaps – so he could not use his legs to push up, open his lungs, and draw breath. I grew nauseous imagining Doubtful Thomas digging his hands into the lance wound under Christ’s rib cage.

Educated in Catholic grade schools, I knew the various explanations for Christ’s terrible death. He died to fulfill Old Testament prophesies. He died to redeem humanity. He died because he brought a revolutionary message of humility, poverty, and love. He died because he challenged the power of his Roman and Jewish rulers. He died, simply, to save the world.

I began to think about the spiritual practices in the Catholics I knew. I didn’t know anyone who was giving up much more than a percentage of their income to the Church much less putting their lives in danger to save the world.

When I asked myself how so many people could insist that Catholicism was the one, true faith while no one was willing to walk the same paths as Christ, the first cracks appeared in the wall of denial I called “faith.” Simply put, I looked around and couldn’t find any Christs.

As I grew up, the wall crumbled. The first time I masturbated I was convinced the Virgin Mary would appear to haunt me. The day after I lost my virginity, I went to Mass expecting to feel God biting me with guilt. All I could feel was joy that I could share such a wonderful feeling with a lover. I finally allowed myself to accept my disbelief and started asking questions. How could people professing love for the world propagate a message rooted in guilt, self-denial, and shame?

I became angry. I felt completely betrayed. I saw a world filled with spiritually dead people. The only people I knew speaking about spirituality were liars. So, I took my anger too far and decided that spirituality itself must be dead.

Giving up on spirituality, the world became a dead zone filled simply with material. Yes, I worked to ease human suffering. But, I only did this out of a strange sense of duty, out of the remnants of Catholic guilt that seeped so thoroughly into my soul that I knew no other way to function.

I hung on to this perspective for a few years, denying the voices singing around me, and essentially strangling my own spirituality to death. The dominant culture is cutting vocal cords and I stuffed my ears with despair. Perhaps, it was only logical – committing spiritual suicide as I did – that physical suicide came next.

***

The TMT project on Mauna Kea and others like it around the world are expressions of a culture determined to commit suicide. And I’m not talking about a metaphoric, cultural suicide. I’m talking real, physical suicide. I’m talking about the destruction of the planet’s life support systems.

How else do you explain storing a 5,000 gallon hazardous chemical waste container above the largest freshwater aquifer on Hawai’i Island like the TMT builders want to do?

To stop the TMT project, to stop the genocide of indigenous peoples, and to save the world, I believe we need to empower spiritualities that learned how to live in balance with their land bases. We need to empower indigenous spiritualities around the world.

Our predicament today is even more dire than in 1973 when Deloria wrote in God Is Red, “Ecologists project a world crisis of severe intensity within our lifetime…It is becoming increasingly apparent that we shall not have the benefits of this world for much longer. The imminent and expected destruction of the life cycle of world ecology can be prevented by a radical shift in outlook from our present naive conception of this world as a testing ground of abstract morality to a more mature view of the universe as a comprehensive matrix of life forms. Making this shift in viewpoint is essentially religious, not economic or political.”

I need to be absolutely clear before I write on: Personal spiritual transformation is not going to save us from anything, but our own personal despair. What we need are spiritual transformations on the cultural scale, but we’re not going to achieve these transformations when too many insist that spirituality is worthless.

Just like we will not recycle our way to the revolution, successfully petition Shell to stop murdering the Niger River Delta, or write a persuasive enough essay to convince those in power to stop the TMT project, personal spiritual transformation is too often a distraction from the need for physical action in the physical world.

I’ve written that no emotion – including despair – can kill you. You can kill you. You can put a gun to your temple, snort up a bottle of pills, or run the exhaust into your sealed-off car, and kill yourself. But, in each instance it will not be an emotional or a spiritual state that will kill you. It will be a physical action that kills you. This also means that it will take physical actions to bring you out of despair. This is as true on the cultural level as it is on the personal.

The dominant culture suffers from a profound sense of despair. It says that destruction is human nature. It says that greed is universal. It says that we already live in the best possible world and this world is violent, evil, and hateful. It would be one thing if the dominant culture was content to hold this despair in its heart, content to stay in bed all day with the paralyzing despair that many of us have felt.

The problem for life on this planet – the problem at Mauna Kea – is the dominant culture manifests its despair physically. Once the dominant culture isolated itself from the rest of life, it grew resentful. It became angry. And now it seeks a murder suicide. Left unchecked, it will kill everything and then turn the gun on itself.

In order to turn the spiritual tide we must protect places like Mauna Kea. If we lose the sacred, we won’t be far behind.

From San Diego Free Press

Find an index of Will Falk’s “Protecting Mauna Kea” essays, plus other resources, at:

Deep Green Resistance Hawai’i: Protect Mauna Kea from the Thirty Meter Telescope

by DGR News Service | Oct 7, 2014 | Biodiversity & Habitat Destruction, Colonialism & Conquest, Protests & Symbolic Acts, Toxification

By Sacred Mauna Kea

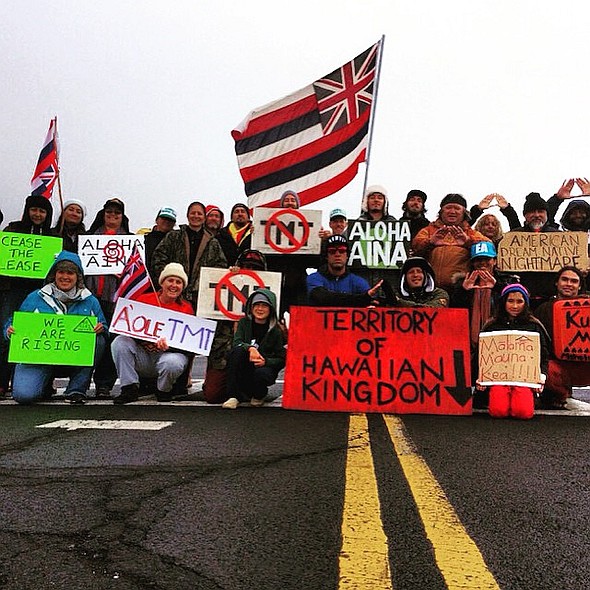

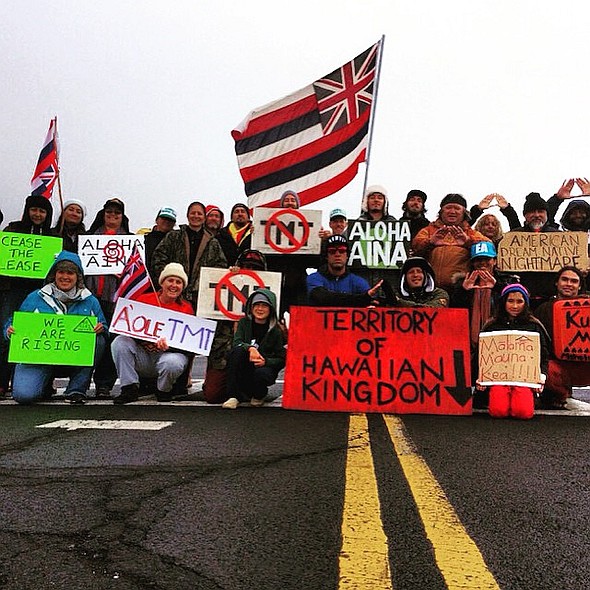

Mauna Kea Protest

Tuesday, October 7, 2014 — 7am to 2pm,

Saddle Road at the entrance to the Mauna Kea Observatory Road

Native Hawaiians and non-Hawaiians will gather for a peaceful protest against the Astronomy industry and the “State of Hawaii’s” ground- breaking ceremony for a thirty-meter telescope (TMT) on the summit of Mauna Kea.

Native Hawaiians and non-Hawaiians will gather for a peaceful protest

against the Astronomy industry and the “State of Hawaii’s” ground-

breaking ceremony for a thirty-meter telescope (TMT) on the summit of

Mauna Kea.

CULTURAL ISSUES: Mauna Kea is sacred to the Hawaiian people, who

maintain a deep connection and spiritual tradition there that goes

back millennia.

“The TMT is an atrocity the size of Aloha Stadium,” said Kamahana

Kealoha, a Hawaiian cultural practitioner. “It’s 19 stories tall,

which is like building a sky-scraper on top of the mountain, a place

that is being violated in many ways culturally, environmentally and

spiritually.” Speaking as an organizer of those gathering to protest,

Kealoha said, “We are in solidarity with individuals fighting against

this project in U.S. courts, and those taking our struggle for

de-occupation to the international courts. Others of us must protest

this ground-breaking ceremony and intervene in hopes of stopping a

desecration.”

Clarence “Ku” Ching, longtime activist, cultural practitioner, and a

member of the Mauna Kea Hui, a group of Hawaiians bringing legal

challenges to the TMT project in state court, said, “We will be

gathering at Pu’u Huluhulu, at the bottom of the Mauna Kea Access

Road, and we will be doing prayers and ceremony for the mountain.”

When asked if he will participate in protests, he said, “We’re on the

same side as those who will protest, but my commitment to Mauna Kea is

in this way. We are a diverse people…everyone has to do what they know

is pono.”

ENVIRONMENTAL ISSUES: The principle fresh water aquifer for Hawaii

Island is on Mauna Kea, yet there have been mercury spills on the

summit; toxins such as Ethylene Glycol and Diesel are used there;

chemicals used to clean telescope mirrors drain into the septic

system, along with half a million gallons a year of human sewage that

goes into septic tanks, cesspools and leach fields.

“All of this poisonous activity at the source of our fresh water

aquifer is unconscionable, and it threatens the life of the island,”

said Kealoha. “But that’s only part of the story of this mountain’s

environmental fragility. It’s also home to endangered species, such as

the palila bird, which is endangered in part because of the damage to

its critical habitat, which includes the mamane tree.”

LEGAL ISSUES: Mauna Kea is designated as part of the Crown and

Government lands of the Hawaiian Kingdom.

Professor Williamson PC Chang, from the University of Hawaii’s

Richardson School of Law, said, “The United States bases its claim to

the Crown and Government land of the Hawaiian Kingdom on the 1898

Joint Resolution of Congress, but that resolution has no power to

convey the lands of Hawaii to the U.S. It’s as if I wrote a deed

saying you give your house to me and I accepted it. Nobody gave the

land to the U.S., they just seized it.”

“Show us the title,” said Kealoha. “If the so-called ‘Treaty of

Annexation’ exists, that would be proof that Hawaiian Kingdom citizens

gave up sovereignty and agreed to be part of the United States 121

years ago. But we know that no such document exists. The so-called

‘state’ does not have jurisdiction over Mauna Kea or any other land in

Hawaii that it illegally leases out to multi-national interests.”

“I agree with how George Helm felt about Kahoolawe,” said Kealoha. “He

wrote in his journal: ‘My veins are carrying the blood of a people who

understood the sacredness of land and water. Their culture is my

culture. No matter how remote the past is it does not make my culture

extinct. Now I cannot continue to see the arrogance of the white man

who maintains his science and rationality at the expense of my

cultural instincts. They will not prostitute my soul.’”

“We are calling on everyone, Hawaiians and non-Hawaiians alike, to

stand with us, to protect Mauna Kea the way George and others

protected Kahoolawe. I ask myself every day, what would George Helm

do? Because we need to find the courage he had and stop the

destruction of Mauna Kea.”

From Sacred Mauna Kea: http://sacredmaunakea.wordpress.com/