by DGR News Service | May 25, 2021 | Biodiversity & Habitat Destruction, Lobbying, Movement Building & Support, Protests & Symbolic Acts

Proposal called for 4,600 acres of clearcuts, bulldozing up to 56 miles of roads on public lands just outside of Yellowstone

This article originally appeared on Counterpunch.

WEST YELLOWSTONE, MONTANA— Following a challenge by multiple conservation groups, the U.S. Forest Service announced Thursday that it was halting a plan to clearcut more than 4,600 acres of native forests, log across an additional 9,000 acres and bulldoze up to 56 miles of road on lands just outside Yellowstone National Park in the Custer Gallatin National Forest.

In April, the Center for Biological Diversity, WildEarth Guardians, Alliance for the Wild Rockies and Native Ecosystems Council challenged the South Plateau project, saying it would destroy habitat for grizzly bears, lynx, pine martens and wolverines. The logging project would have destroyed the scenery and solitude for hikers using the Continental Divide National Scenic Trail, which crosses the proposed timber-sale area.

“This was another one of the Forest Service’s ‘leap first, look later’ projects where the agency asks for a blank check to figure out later where they’ll do all the clearcutting and bulldozing,” said Adam Rissien, a rewilding advocate at WildEarth Guardians. “Logging forests under the guise of reducing wildfires is not protecting homes or improving wildlife habitat, it’s just a timber sale. If the Forest Service tries to revive this scheme to clearcut native forests and bulldoze new roads in critical wildlife habitat just outside of Yellowstone, we’ll continue standing against it.”

In response to the group’s challenge, the Forest Service said it was withdrawing the South Plateau project until after it issues a new management plan for the Custer-Gallatin National Forest this summer. Then it plans to prepare a new environmental analysis of the project with “additional public involvement” to ensure the project complies with the new forest plan.

“This is a good day for the greater Yellowstone ecosystem and for the grizzlies, lynx and other wildlife that call it home,” said Ted Zukoski, a senior attorney at the Center for Biological Diversity. “The Forest Service may revive this destructive project in a few months, but for now this beautiful landscape is safe from chainsaws and bulldozers.”

The project violated the National Environmental Policy Act by failing to disclose precisely where and when it would bulldoze roads and clearcut the forest, which made it impossible for the public to understand the project’s impacts, the groups said in their April objection. The project allowed removal of trees more than a century old, which provide wildlife habitat and store significant amounts of carbon dioxide, an essential component of addressing the climate emergency.

“The South Plateau project was in violation of the forest plan protections for old growth,” said Sara Johnson, director of Native Ecosystems Council and a former wildlife biologist for the Custer Gallatin National Forest. “The new forest plan has much weaker old-growth protections standards. That is likely why they pulled the decision — so they can resign it after the new forest plan goes into effect.”

“The Forest Service needs to drop the South Plateau project and quit clearcutting old-growth forests,” said Mike Garrity, executive director of the Alliance for the Wild Rockies. “Especially clearcutting and bulldozing new logging roads in grizzly habitat on the border of Yellowstone National Park.”

Contacts:

Adam Rissien, WildEarth Guardians, (406) 370-3147, arissien@wildearthguardians.org

Ted Zukoski, Center for Biological Diversity, (303) 641-3149, tzukoski@biologicaldiversity.org

Michael Garrity, Alliance for the Wild Rockies, (406) 459-5936, wildrockies@gmail.com

Dr. Sara Jane Johnson, Native Ecosystems Council, (406) 579-3286, sjjohnsonkoa@yahoo.com

by DGR News Service | May 19, 2021 | Biodiversity & Habitat Destruction, Colonialism & Conquest, Culture of Resistance, Direct Action, Indigenous Autonomy, Listening to the Land, Lobbying, Mining & Drilling, Movement Building & Support, Obstruction & Occupation, Repression at Home, Toxification, White Supremacy

In this statement, Atsa koodakuh wyh Nuwu (the People of Red Mountain), oppose the proposed Lithium open pit mines in Thacker Pass. They describe the cultural and historical significance of Thacker Pass, and also the environmental and social problems the project will bring.

We, Atsa koodakuh wyh Nuwu (the People of Red Mountain) and our native and non-native allies, oppose Lithium Nevada Corp.’s proposed Thacker Pass open pit lithium mine.

This mine will harm the Fort McDermitt Paiute-Shoshone Tribe, our traditional land, significant cultural sites, water, air, and wildlife including greater sage grouse, Lahontan cutthroat trout, pronghorn antelope, and sacred golden eagles. We also request support as we fight to protect Thacker Pass.

”Lithium Nevada Corp. (“Lithium Nevada”) – a subsidiary of the Canadian corporation Lithium Americas Corp. – proposes to build an open pit lithium mine that begins with a project area of 17,933 acres. When the Mine is fully-operational, it would use 5,200 acre-feet per year (equivalent to an average pumping rate of 3,224 gallons per minute) in one of the driest regions in the nation. This comes at a time when the U.S. Bureau of Reclamation fears it might have to make the federal government’s first-ever official water shortage declaration which will prompt water consumption cuts in Nevada. Meanwhile, despite Lithium Nevada’s characterization of the Mine as “green,” the company estimates in the FEIS that, when the Mine is fully-operational, it will produce 152,703 tons of carbon dioxide equivalent emissions every year.

Mines have already harmed the Fort McDermitt tribe.

Several tribal members were diagnosed with cancer after working in the nearby McDermitt and Cordero mercury mines. Some of these tribal members were killed by that cancer.

In addition to environmental concerns, Thacker Pass is sacred to our people. Thacker Pass is a spiritually powerful place blessed by the presence of our ancestors, other spirits, and golden eagles – who we consider to be directly connected to the Creator. Some of our ancestors were massacred in Thacker Pass. The name for Thacker pass in our language is Peehee mu’huh, which in English, translates to “rotten moon.” Pee-hee means “rotten” and mm-huh means “moon.” Peehee mu’huh was named so because our ancestors were massacred there while our hunters were away. When the hunters returned, they found their loved ones murdered, unburied, rotting, and with their entrails spread across the sage brush in a part of the Pass shaped like a moon. To build a lithium mine over this massacre site in Peehee mu’huh would be like building a lithium mine over Pearl Harbor or Arlington National Cemetery. We would never desecrate these places and we ask that our sacred sites be afforded the same respect.

Thacker Pass is essential to the survival of our traditions.

Our traditions are tied to the land. When our land is destroyed, our traditions are destroyed. Thacker Pass is home to many of our traditional foods. Some of our last choke cherry orchards are found in Thacker Pass. We gather choke cherries to make choke cherry pudding, one of our oldest breakfast foods. Thacker Pass is also a rich source of yapa, wild potatoes. We hunt groundhogs and mule deer in Thacker Pass. Mule deer are especially important to us as a source of meat, but we also use every part of the deer for things like clothing and for drumskins in our most sacred ceremonies.

Thacker Pass is one of the last places where we can find our traditional medicines.

We gather ibi, a chalky rock that we use for ulcers and both internal and external bleeding. COVID-19 made Thacker Pass even more important for our ability to gather medicines. Last summer and fall, when the pandemic was at its worst on the reservation, we gathered toza root in Thacker Pass, which is known as one of the world’s best anti-viral medicines. We also gathered good, old-growth sage brush to make our strong Indian tea which we use for respiratory illnesses.

Thacker Pass is also historically significant to our people.

The massacre described above is part of this significance. Additionally, when American soldiers were rounding our people up to force them on to reservations, many of our people hid in Thacker Pass. There are many caves and rocks in Thacker Pass where our people could see the surrounding land for miles. The caves, rocks, and view provided our ancestors with a good place to watch for approaching soldiers. The Fort McDermitt tribe descends from essentially two families who, hiding in Thacker Pass, managed to avoid being sent to reservations farther away from our ancestral lands. It could be said, then, that the Fort McDermitt tribe might not be here if it wasn’t for the shelter provided by Thacker Pass.

We also fear, with the influx of labor the Mine would cause and the likelihood that man camps will form to support this labor force, that the Mine will strain community infrastructure, such as law enforcement and human services. This will lead to an increase in hard drugs, violence, rape, sexual assault, and human trafficking. The connection between man camps and missing and murdered indigenous women is well-established.

Finally, we understand that all of us must be committed to fighting climate change. Fighting climate change, however, cannot be used as yet another excuse to destroy native land. We cannot protect the environment by destroying it.

Sign the petition from People of Red Mountain: https://www.change.org/p/protect-thacker-pass-peehee-mu-huh

Donate: https://www.classy.org/give/423060/#!/donation/checkout

For more on the Protect Thacker Pass campaign

#ProtectThackerPass #NativeLivesMatter #NativeLandsMatter

by DGR News Service | May 18, 2021 | Biodiversity & Habitat Destruction, Culture of Resistance, Education, Indigenous Autonomy, Indirect Action, Lobbying, Movement Building & Support, Repression at Home

- The Philippine government has suspended work on a bridge that would connect the islands of Coron and Culion in the coral rich region of Palawan.

- Activists, Indigenous groups and marine experts say the project would threaten the rich coral biodiversity in the area as well as the historical shipwrecks that have made the area a prime dive site.

- The Indigenous Tagbanua community, who successfully fought against an earlier project to build a theme park, say they were not consulted about the bridge project.

- Preliminary construction began in November 2020 despite a lack of government-required consultations and permits, and was ordered suspended in April this year following the public outcry.

This article originally appeared on Mongabay.

Featured image: The Indigenous Tagbanua community of Culion has slammed the project for failing to obtain their permission that’s required under Philippine law. Image by anne jimenez via Wikimedia Commons (CC BY 2.0).

by Keith Anthony S. Fabro

PALAWAN, Philippines — Nicole Tayag, 30, learned to snorkel at 5 when her father took her to the teeming waters of Coron to scout for potential tourist destinations back in 1995. One particularly biodiverse site they found was the Lusong coral garden, southwest of this island town in the Philippines’ Palawan province.

“Even just at the surface, I saw how lively the place was,” Tayag told Mongabay. “We drove our boat for so many times that I remember the passage as one of the places I see dolphins jumping and rays flying up the water. It has inspired me to see more underwater, which led me to my career as a scuba diver instructor now.”

Tayag said she holds a special place in her heart for Lusong coral garden. So when she heard that a government-funded bridge would be built through it, she said was concerned about its impact on the marine environment and tourism industry. Before the pandemic, the 644-hectare (1,591-acre) Bintuan marine protected area (MPA), which covers this dive site, received an average of 3,000 tourists weekly, generating up to 259 million pesos ($5.4 million) in annual revenue. Bintuan is one of the MPAs in the Philippines considered by experts as being managed effectively.

The planned 4.2 billion peso ($88.6 million) road from Coron to the island of Culion would run just over 20 kilometers (12.5 miles), of which only about an eighth would constitute the actual bridge span, according to a government document obtained by Mongabay.

Tayag said they’ve been hearing about the project for 20 years now. “[I] didn’t give much thought about it before, really.” Then, in March this year, Mark Villar, secretary of the Philippine Department of Public Works and Highways (DPWH), posted the project’s conceptual design on his Facebook page.

Tayag said she was shocked that the project was finally going through. “I was even more shocked when I realized it’s so close to historical dive sites and to coral garden,” she said.

Part of President Rodrigo Duterte’s “Build, Build, Build” infrastructure program, construction of the Coron-Culion bridge was scheduled from 2020 to 2023. By November 2020, site clearing had already started in the area designated for the bridge’s access road. But on April 7 this year, the Philippine government announced it was suspending the project to ensure mitigating measures for its environmental impact are in place. This follows a public outcry from academics, civil society groups and nonprofit organizations that say the project is fraught with risks and irregularities.

“Without the concerned citizens and organizations who raised the alarm bell in this project, this would have gone in the way of so many so-called infrastructure projects, which are disregarding our sacred rights to a balanced and healthful ecology,” said Gloria Ramos, head of the NGO Oceana Philippines.

Cultural heritage collapse

Tayag is part of a group, Buklod Calamianes, that initiated an online petition seeking to stop the project. They warned of the damage that the bridge construction could pose to the marine environment, as it would sit within a 5-km (3-mi) radius of seven of the top underwater attractions in Coron and Culion. In addition to the Lusong coral garden, these dive sites include six Japanese shipwrecks from World War II.

“Heavy sedimentation from the construction will settle upon these fragile shipwrecks and potentially cause the collapse of these precious historical underwater sites,” said the petition, which has been signed by more than 19,000 people.

Palawan Studies Center executive director Michael Angelo Doblado said the shipwrecks need to be protected because they’re historically significant heritage sites of local and global importance. “These are evidence that important battles between the American and Japanese air and sea forces happened there.”

Doblado, who is also a professor of history at Palawan State University, said the occurrence of these shipwrecks also highlights that the Calamianes island group that includes Coron and Culion was important for the Japanese forces, whose weapons and other equipment relied on Coron as a source of manganese.

“For these wrecks and its local importance to Coron and its people, that would be left to them to decide,” he told Mongabay. “Is it really important for them historically as a municipality that they will be willing to preserve and protect it? Or will they be willing to sacrifice and give it up as a price for development?

“It also begs the question, if tourism is one of the major earners of Coron, and the proposed bridge … will boost its tourism, is it not ironic that the shipwrecks … will be directly affected by this infrastructure project that is supposed to boost tourism?”

The government had touted the bridge as improving connectivity between the islands to boost the tourism and agriculture sectors, among other benefits. But if it really wants to help the local tourism sector, Doblado said, the government “should have carried out a construction plan that skirts or avoids destroying or affecting these shipwrecks which are famous dive sites and considered as artificial reefs that promote aquatic growth and diversity in that area.”

This would swell the construction cost, he said, but would be vital to saving not only the historical underwater ruins but the marine environment and tourism industry in the long run.

Impact on marine ecosystems

The Philippines has around 25,000 square kilometers (9,700 square miles) of coral reefs, the world’s third-largest extent, and its waters are known for the highest biodiversity of corals and shore fishes, a 2019 study noted. However, the same study showed that the country, located at the apex of the Pacific Coral Triangle, lost about a third of its reef corals over the past decade, and none of the reefs surveyed were in a condition that qualified as “excellent.”

The bridge project added to concerns about the loss of hard-coral cover. Tayag’s group estimated that it would affect 334 hectares (825 acres) of corals, as well as 140 hectares (346 acres) of mangroves. It said the heavy sedimentation, runoff and silt from the construction could cloud the water, blocking the sunlight that’s essential for the growth of the algae that, in turn, nourish the corals.

Coral expert Wilfredo Licuanan from De La Salle University in Manila told Mongabay that the corals and the abundance of sea life they support are quite sensitive to water quality change due to sedimentation. “If you have sediments … their feeding structures are clogged, light penetration is hindered … and then there’s general smothering of life on the sea bottom.”

When corals are undernourished, he said, it can prevent the calcium carbonate accumulation that constitutes reef growth and that takes tens of thousands of years. “If the corals are not able to produce enough calcium carbonate, your reef is not able to continue to grow and … will start eroding,” Licuanan said.

Once that happens, the reefs will not be able to keep up with climate change-induced sea level rise, and will cease to protect the coastlines from big waves and to serve as habitat for many other species, including those that feed fishing communities. “So, all the ecosystem services of coral reefs are dependent on the position of calcium carbonate skeleton,” Licuanan said.

“Any construction activity, be it road building, resort construction, anything of that sort requires that you move earth,” Licuanan said. “You dig, you relocate soil, and so on. And almost always, that means a lot of the soil gets mobilized and is brought to the sea, causing sedimentation.”

That impact to the reef ecosystem will reverberate up to the residents who depend on it for their livelihoods, said Miguel Fortes, a marine scientist and professor at the University of the Philippines. “If you destroy one, you’re actually destroying the other,” he said in an Oceana online forum.

Fortes said it takes about 35 years for damaged coral reefs to recover. That compares to about 25 years for mangroves and a year for seagrass, both of which are useful in mitigating climate change, he said. In Coron and Culion, these ecosystems provide estimated annual economic benefits of 3.7 billion pesos ($77.2 million), on top of the 4.1 billion pesos ($85.2 million) generated by the islands’ recreation zones.

Coron Bay’s fisheries production is an important spawning and nursery ground, said Jomel Baobao, a fisheries management specialist with the nonprofit Path Foundation Inc., one of the partner implementers of the USAID Fish Right project. The five communities adjacent to the bridge project alone stand to benefit from a total estimated yield of 89 million pesos ($1.8 million) annually.

“A USAID-funded larval dispersal study showed that Bintuan area is the sink for larvae that come from different sources, making it a rich nursery ground,” Baobao told Mongabay. He added that Coron Bay serves to funnel larvae from the Sulu Sea and West Philippine Sea, and any disruption to that flow could affect fishing yields in Bintuan and other areas.

“The narrowest portion in the bay located in Bintuan where the bridge will be constructed is significant to water exchange between these two seas,” Baobao said. This might be affected if there will be ecosystem loss or destruction in the area because of the bridge.”

The area’s reefs are home to economically important species such as red grouper, lobster and round scad, as well as giant clams, according to the Bureau of Fisheries and Aquatic Resources. Among the coral species that flourish around the Calamianes island group are two endangered ones: Pectinia maxima and Anacropora spinosa. In the Philippines, the latter is found only in the Calamianes.

No green permits

Preliminary tree cutting and clearing of the road leading to the bridge entrance reportedly began in November 2020, raising fears that it could trigger siltation that could jeopardize the marine park.

In a 2020 paper, Licuanan said that management actions, such as enhanced regulation of road construction on slopes leading to the sea and rivers that open into the sea, and consequent limitations on government infrastructure programs that impinge on these critical areas, are crucial in conserving the country’s remaining coral reefs.

“Road building practices locally are particularly destructive because they [the DPWH and private contractors] rarely prioritize soil conservation,” he told Mongabay.

But despite the recent activity, the project has not received the green light from the Palawan Council for Sustainable Development (PCSD), a provincial government agency. PCSD spokesman John Vincent Fabello told Mongabay that no strategic environmental plan (SEP) clearance has been issued to the DPWH for the project. The clearance would essentially guarantee that the high-impact project is located outside ecologically critical zones like marine parks.

“They [DPWH] don’t have an SEP clearance yet,” Fabello said. “Government big-ticket projects still have to [go] through the SEP clearance system of the PCSD. Administrative fines shall be imposed if building commences without the necessary clearance and permits from PCSD and related agencies.”

The Department of Environment and Natural Resources (DENR) said it will also require the DPWH to undertake an environmental impact assessment to obtain an environmental compliance certificate and tree cutting permit for the project. “Government projects will still go through the permitting; you have to follow the process … but it will be faster,” said DENR regional director Maria Lourdes Ferrer.

The DPWH confirmed it had not undertaken the required public consultations, feasibility study, or permit applications prior to the start of construction activities. DPWH regional director Yolanda Tangco said they fast-tracked the construction work because the initial 250 million pesos ($5.2 million) in project funding released to the agency in 2020 would have to be returned to the treasury if it was not spent within two years.

Fortes said this reasoning is unacceptable because projects should not only be politically expedient but also based on scientific evidence and actual user needs.

“To me, this means money still supersedes more vital imperatives [such as] cultural and ecological,” he said. “Poor planning is evident here because it entails huge sacrifices.”

Tangco said her office expects to receive additional construction funding for 2021 to 2023 from the national government. “But if we have decided not to continue it, we will remove it [in our proposal]. Most probably, we will revert the funding and terminate the contract,” she said.

She added that in the feasibility study expected to be completed in July 2021, the public works office is considering two more route options: “Our alignment isn’t fixed. If we can find an alignment with lesser impacts to the environment and Indigenous people, we will pursue that and issue variation and change orders [to the contractor].”

Indigenous communities fight back

The Indigenous Tagbanua community of Culion has slammed the project for failing to obtain their permission through a process of free, prior and informed consent (FPIC), required under Philippine law.

“We don’t want that bridge here because we fear that it will affect many — our seas, our livelihoods, our lands we inherited from our ancestors,” Indigenous federation chairman Larry Sinamay, who organized a rally on April 5, told Mongabay. “Where would we get our food when our place is destroyed by this project?”

“The social and sacred value of this traditional space to the Tagbanua should be respected by every member of the community, even us outsiders, tourists and developers,” said Kate Lim, an archaeologist who has conducted studies in the region. “The concept of ancestral domain is that it’s communal and utilized by everyone and not just by one sector only.”

In a letter dated March 31, the federation of 24 Tagbanua communities appealed to the national government to halt the project’s preliminary construction activities, pending impact assessments.

“If we receive no response to our plea, we will be forced to seek legal remedies to fight for our Indigenous rights provided under the Philippine Constitution, Indigenous Peoples’ Rights Act, and other laws related to environment and natural resources,” the federation said at the time.

The Tagbanuas have experience standing up to projects they see as imperiling their environment and culture. In 2017, they banded together to stop a proposed Nickelodeon theme park, which also lacked the necessary scientific studies, consultations and permits.

“Even if we are battling a pandemic, we can’t forget that our battle to protect Palawan’s natural resources must go on,” said Anna Oposa, executive director of Save Philippine Seas, who joined the Tagbanuas in fighting the Nickelodeon project. “The Tagbanua IPs have the experience and power to block or at the very least significantly delay this potentially destructive project and come to a consensus with other stakeholders.”

While the public pressure has prompted the government to suspend the project, the community says it isn’t dropping its guard.

“In a time of pandemic and lockdowns, projects are easily sneaked in and started out of the public’s eye who are confined in their homes,” Tayag said.

“We are closely monitoring these bateltelan [hard-headed] officials. We trust that the government offices looking into this project will do what is right and not just focus on its ‘good intention.’”

Citations:

Licuanan, W. Y., Robles, R., & Reyes, M. (2019). Status and recent trends in coral reefs of the Philippines. Marine Pollution Bulletin, 142, 544-550. doi:10.1016/j.marpolbul.2019.04.013

Licuanan, W. Y. (2020). Current management, conservation, and research imperatives for Philippine coral reefs. Philippine Journal of Science, 149(3), ix-xii. Retrieved from https://philjournalsci.dost.gov.ph/publication/regular-issues/past-issues/98-vol-149-no-3-september-2020/1225-current-management-conservation-and-research-imperatives-for-philippine-coral-reefs-2

by DGR News Service | May 17, 2021 | Biodiversity & Habitat Destruction, Education, Indirect Action, Lobbying, Movement Building & Support, Protests & Symbolic Acts, Toxification

Nearly 100,000 people have signed a petition calling for the closure of a controversial oil and gas facility that has sickened residents of the U.S. Virgin Island. We in DGR deeply care about social justice, so we think it is important to expect president Biden to act against structural racism by shutting down an oil and gas facility that is poisoning a predominantly black community. But there are many oil refineries in the world and each one is poisoning their surrounding communities, human and nunhuman. As long as this cultures addiction to fossil fuels continues, it will obviously continue poisoning human and nonhuman communities.

This article was produced by Earth | Food | Life, a project of the Independent Media Institute.

By Reynard Loki

A controversial oil refinery on St. Croix, one of the U.S. Virgin Islands, is in the government’s crosshairs after a third incident in just three months has sickened people. On May 5, after gaseous fumes were released from one of the oil refining units of Limetree Bay Refining, residents of the unincorporated Caribbean territory reported a range of symptoms, including burning eyes, nausea and headaches, with at least three people seeking medical attention at the local hospital. At its peak in 1974, the facility, which opened in 1966, was the largest refinery in the Americas, producing some 650,000 barrels of crude oil a day. It restarted operations in February after being shuttered for the past decade.

A Limetree spokesperson said that there was a release of “light hydrocarbon odors” resulting from the maintenance on one of the refinery’s cokers, high heat level processing units that upgrade heavy, low-value crude oil into lighter, high-value petroleum products. The noxious odor stretched for miles around the refinery, remaining in the air for days and prompting the closure of two primary schools, a technical educational center and the Bureau of Motor Vehicles (BMV), which local officials said was shuttered because its employees “are affected by the strong, unpleasant gas like odor, in the atmosphere.”

Limetree and the U.S. government conducted their own air quality testing, with different results. The National Guard found elevated levels of sulfur dioxide, while the company said it detected “zero concentrations” of the chemical just hours later. “We will continue to monitor the situation, but there is the potential for additional odors while maintenance continues,” said Limetree, which is backed by private equity firms EIG and Arclight Capital, the latter of which has ties to former President Donald Trump. “We apologize for any impact this may have caused the community.”

The May 5 incident follows two similar incidents in April at the refinery that the Virgin Islands Department of Planning and Natural Resources (DPNR) concluded were caused by the emission of excess sulfur dioxide from the burning of hydrogen sulfide, one of the impurities in petroleum coke, a coal-like substance that accounts for nearly a fifth of the nation’s finished petroleum product exports, mainly going to China and other Asian nations, where it is used to power manufacturing industries like steel and aluminum. Days after the U.S. Environmental Protection Agency (EPA) told the company that it was violating the Clean Air Act after the April incidents, Limetree agreed to resume sulfur dioxide monitoring, while contesting the violation. “If EPA makes a determination that the facility’s operations present an imminent risk to people’s health, consistent with its legal authorities, it will take appropriate action to safeguard public safety,” the agency said in a statement. The Biden EPA withdrew a key federal pollution permit for Limetree on March 25, but stopped short of shutting down the facility altogether.

Care2 has launched a public petition—already signed by more than 98,000 people—urging President Biden to shut down the Limetree Bay Refining facility. The petition also notes the risk that the refinery poses to the island’s biodiverse wildlife, saying that “turtles, sharks, whales, and coral reefs… [are] threatened by the Limetree Bay Refining plant—both by what it’s done in the past, and by what it’s spewing right now.” The group also frames the human rights and environmental justice aspect of the ongoing public health situation on the island in historical terms: “On top of the obvious problem that no person should be poisoned with oil, St. Croix is an island with a highly disenfranchised population. The vast majority of residents are Black, the [descendants] of enslaved Africans brought to work on sugar and cotton plantations. For generations, the U.S. government has cared little about the well-being of people there.” (One recent example happened in the wake of Hurricanes Irma and Maria, which landed on the island in September of 2017. Even two months after the storms hit, many residents of St. Croix who were evacuated to Georgia were unable to return home, and felt abandoned by the government. “I feel like we are the forgotten people and no one has ever inquired how do we feel,” said one of the St. Croix evacuees at the time.)

After the May 5 incident, Limetree said, “Our preliminary investigations have revealed that units are operating normally.” Perhaps it is normal for such facilities to emit toxic fumes. But what’s not normal is the fact that such fumes should present a constant threat to people and the environment, and that, according to the environmental group Earthjustice, about 90 million Americans live within 30 miles of at least one refinery. Adding insult to injury is the fact that Black people are 75 more likely to live near toxic, air-polluting industrial facilities, according to Fumes Across the Fence-Line, a report produced by the NAACP and the Clean Air Task Force, an air pollution reduction advocacy group. That report also found that more than 1 million African Americans face a disproportionate cancer risk “above EPA’s level of concern” due to the fact that they live in areas that expose them to toxic chemicals emanating from natural gas facilities.

You don’t need to live next door to a refinery to feel its impact on your health; in fact, you can be several miles away. A study conducted last year by researchers at the University of Texas Medical Branch (UTMB) found an increased risk of multiple cancer types associated with living within 30 miles of an oil refinery. “Based on U.S. Census Bureau data, there are more than 6.3 million people over 20 years old who reside within a [30-mile] radius of 28 active refineries in Texas,” said the study’s lead author, Dr. Stephen B. Williams, chief of urology and a tenured professor of urology and radiology at UTMB. “Our team accounted for patient factors (age, sex, race, smoking, household income and education) and other environmental factors, such as oil well density and air pollution and looked at new cancer diagnoses based on cancers with the highest incidence in the U.S. and/or previously suspected to be at increased risk according to oil refinery proximity.”

In granting Limetree’s permit in 2018—a move that E&E News reported was made to “cash in on an international low-sulfur fuel standard that takes effect in January [2020]”—Trump’s EPA said that the refinery’s emissions simply be kept under “plantwide applicability limit.” But then in a September 2019 report on Limetree—which has been at the center of several pollution debacles and Clean Air Act violations for decades—the agency said that “[t]he combination of a predominantly low income and minority population in [south-central] St. Croix with the environmental and other burdens experienced by the residents is indicative of a vulnerable community,” and added the new requirement of installing five neighborhood air quality monitors. “[G]iven several assumptions and approximations… and the potential impacts on an already overburdened low income and minority population, the ambient monitors are necessary to assure continued operational compliance with the public health standards once the facility begins to operate,” the agency stated. Limetree has appealed this ruling with the EPA’s Environmental Appeals Board, arguing that “the EPA requirements are linked to environmental justice concerns that are unrelated to operating within the pollution limits of the permit.”

“It is unclear when the EPA’s appeals board will rule on the permit dispute. The Biden-run EPA could withdraw the permit, and it is also reviewing whether the refinery is a new source of pollution that requires stricter air pollution controls,” reports Reuters, adding that the White House declined to comment.

President Biden has made environmental justice a central part of his policy, including the overhaul of the EPA External Civil Rights Compliance Office, which is responsible for enforcing civil rights laws that prohibit discrimination on the basis of race, color, national origin, sex or disability. “For too long, the EPA External Civil Rights Compliance Office has ignored its requirements under Title VI of the 1964 Civil Rights Act,” states Biden’s environmental justice plan. “That will end in the Biden Administration. Biden will overhaul that office and ensure that it brings justice to frontline communities that experience the worst impacts of climate change and fenceline communities that are located adjacent to pollution sources.”

Now it is time for Biden to make good on his campaign promise. John Walke, senior attorney and director of clean air programs with the Natural Resources Defense Council, told Reuters in March that the situation in St. Croix “offers the first opportunity for the Biden-Harris administration to stand up for an environmental justice community, and take a strong public health and climate… stance concerning fossil fuels.”

Earth | Food | Life contributor Sharon Lavigne has previously written about a similar issue in another region before. Lavigne is the founder and president of RISE St. James, a grassroots faith-based organization dedicated to opposing the siting of new petrochemical facilities in a heavily industrialized area along the Mississippi River between Baton Rouge and New Orleans known as “Cancer Alley.” Writing in Truthout in October 2020 about St. James Parish, Louisiana, the predominantly Black and low-income community where she lives, Lavigne pointed out that “Democratic presidential nominee Joe Biden mentioned St. James Parish in his clean energy plan speech because we’re notorious for having the country’s highest concentration of chemical plants and refineries, [one of] the highest cancer rates, the worst particulate pollution and one of the highest mortality rates per capita from COVID-19 in the nation,” She added, “For those of us living here, it’s not just Cancer Alley; it’s death row.”

The stated mission of the EPA is “to protect human health and the environment.” When so many Americans face a disproportionate cancer risk simply by living near toxic industrial sites such as oil and gas refineries, the EPA is derelict in its duty. The Limetree Bay Refining facility has presented President Biden with an early test of his commitment to environmental justice. Considering the facility’s terrible legacy of ecological and civil rights violations, three new public health incidents in just the past two months, and the disproportionate and ongoing health risks faced by the community’s predominantly Black and low-income population, it is finally time for the federal government to revoke Limetree’s license to operate on St. Croix. This is a perfect chance for President Biden to show the country and the world just how serious he is about environmental justice.

Reynard Loki is a writing fellow at the Independent Media Institute, where he serves as the editor and chief correspondent for Earth | Food | Life. He previously served as the environment, food and animal rights editor at AlterNet and as a reporter for Justmeans/3BL Media covering sustainability and corporate social responsibility. He was named one of FilterBuy’s Top 50 Health & Environmental Journalists to Follow in 2016. His work has been published by Yes! Magazine, Salon, Truthout, BillMoyers.com, AlterNet, Counterpunch, EcoWatch and Truthdig, among others.

by DGR News Service | May 14, 2021 | Biodiversity & Habitat Destruction, Colonialism & Conquest, Culture of Resistance, Defensive Violence, Direct Action, Indigenous Autonomy, Movement Building & Support, People of Color & Anti-racism, Repression at Home, The Problem: Civilization, White Supremacy

Editor’s note: The American Holocaust (a term coined by David Stannard) is the largest genocide in human history. The atrocities are ongoing and being reinforced by fascists like Jair Bolsonaro, providing another example that capitalism and fascism are two sides of the same coin.

Featured image: Indigenous protest, Brazil April 2018. ‘By painting the streets red, we’re showing how much blood has already been shed in the struggle to protect indigenous territories,’ – Sônia Guajajara, a spokeswoman for APIB (Brazilian indigenous organization).

© Marcelo Camargo/Agência Brasil

By Survival International

The land rights of the Xokleng, a tribe that was violently expelled from its territory in the 19th and 20th centuries to make way for European colonists, are now the focus of a landmark court case in Brazil.

The Xokleng were brutally persecuted and evicted by armed militias to make way for European settlers. The Supreme Court hearing into the so-called “Time Limit Trick” could now set the effects of these and subsequent evictions in stone, establishing a precedent which would have far-reaching consequences for indigenous peoples in Brazil.

Other Xokleng communities are also fighting to recover some of their territory. The Xokleng Konglui in Rio Grande do Sul state have launched a ‘retomada’ (reoccupation) of their land, which is now occupied by a national park. The government wants to make it an ‘ecotourism’ destination. © Iami Gerbase/Survival

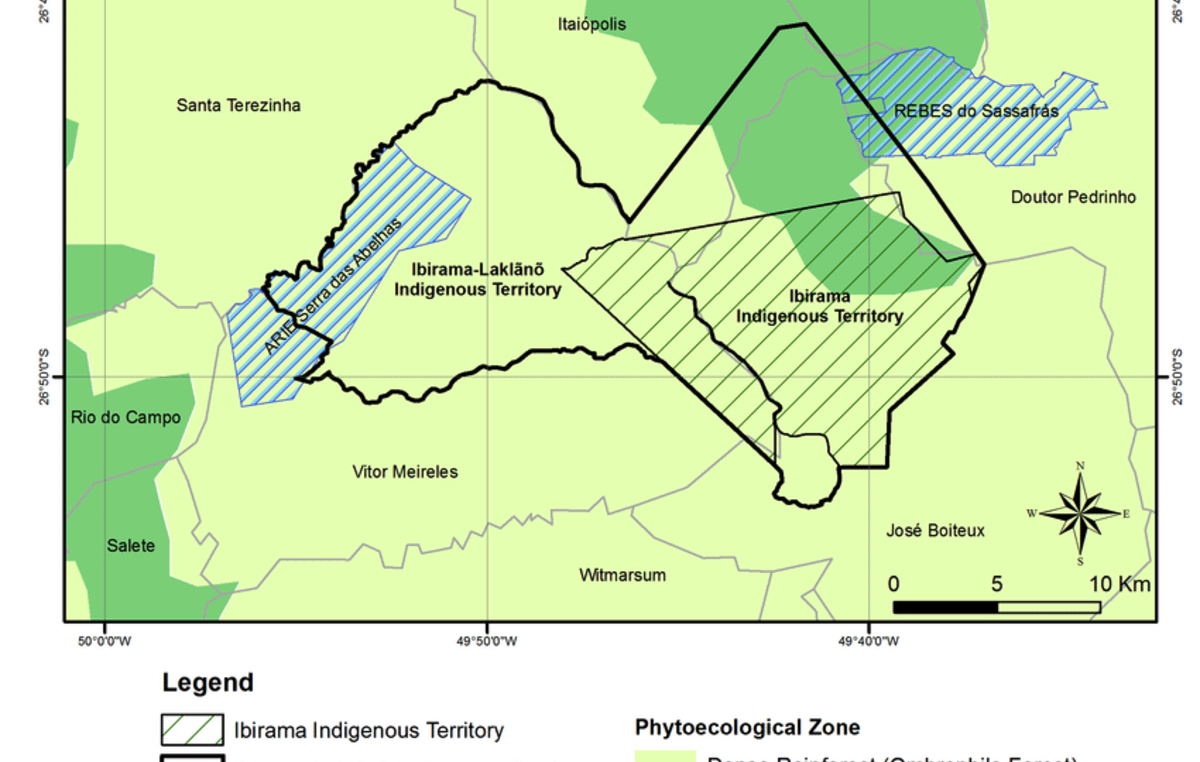

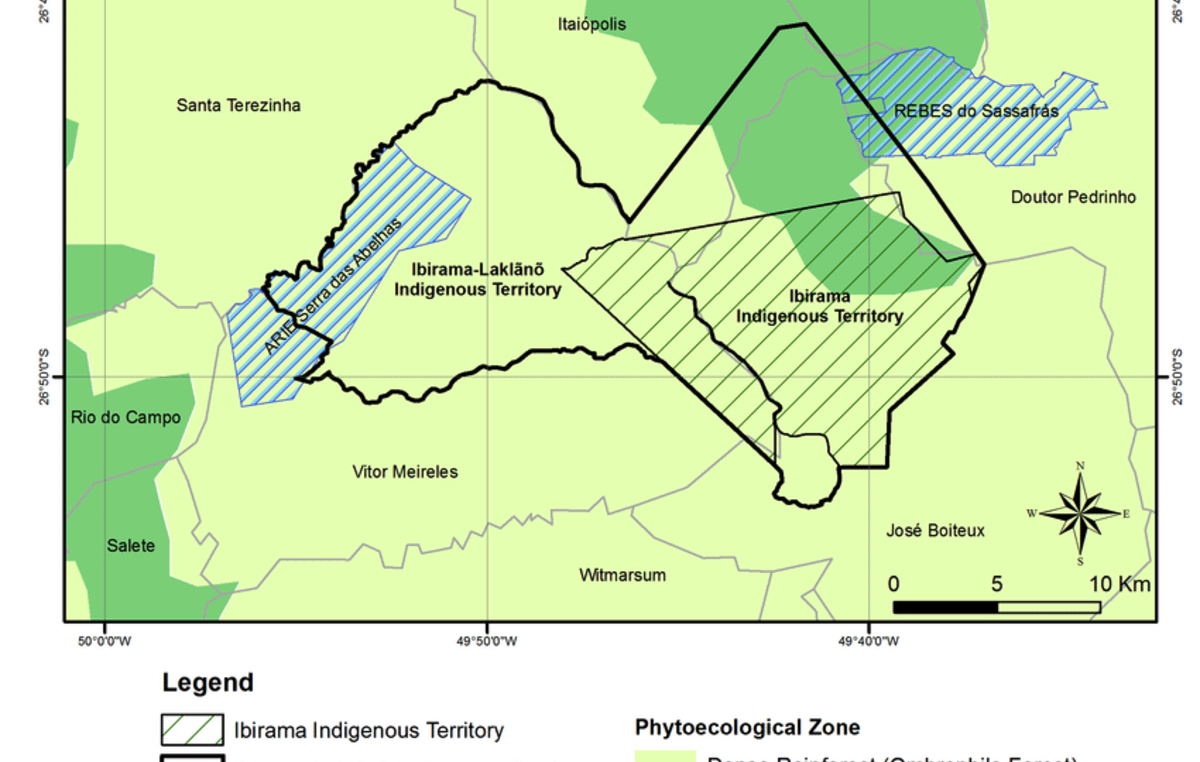

The case centers around the demarcation of the “Ibirama La Klãnõ” Indigenous Territory in the state of Santa Catarina in southern Brazil. If they win, the Xokleng would be able to return to a significant part of their ancestral territory.

However, the official demarcation of the territory has been suspended following a lawsuit filed by non-indigenous residents and a logging company operating in the area. They argue that on October 5, 1988 – the date the Brazilian Constitution was signed – the Xokleng only lived in limited parts of the territory and therefore have no right to most of their original land. If this argument succeeds, it would legitimize centuries of evictions experienced by indigenous peoples throughout Brazil.

The Brazilian government encouraged Europeans to settle on indigenous land, and allocated them large parts of the Xokleng and other indigenous territories at the beginning of the 20th century. It also financed a so-called “Indian-hunting militia”, which accelerated the colonial land grab. This militia specialized in the extermination of indigenous peoples and hunted down the Xokleng.

“The Redskins are interfering with colonization: this interference must be eliminated, and as quickly and thoroughly as possible,” German colonists demanded at the time.

German settlers resented Xokleng attempts to defend their territories, and frequently subjected them to cruel “punitive expeditions.”

The Xokleng territory was continuously reduced over several decades. In the 1970s, a dam was built in the small part that remained.

Map of the current (Ibirama) and planned (Ibirama La Klãnõ) indigenous territory. The expansion of the territory is the cause of the legal dispute. © Marian Ruth Heineberg/Natalia Hanazaki based on data from FUNAI/IBGE/MMA.

If Brazil’s Supreme Court votes in favor of the “Time Limit Trick”, it would have devastating consequences for many other indigenous peoples, and their chances of reclaiming their ancestral territories. It could enable the theft of land that is rightfully owned by hundreds of thousands of tribal and indigenous people. The validity of existing indigenous territories could then also come into question.

Brasílio Priprá, a prominent Xokleng leader, said: “If we didn’t live in a certain part of the territory in 1988, it doesn’t mean it was “no man’s land” or that we didn’t want to be there. The “Time Limit Trick” reinforces the historical violence that continues to leave its mark today.”

Indigenous organizations and their allies, including Survival, began raising fears about the “Time Limit Trick” in 2017, calling it unlawful because it violates the current Brazilian Constitution and international law, which clearly states that indigenous peoples have the right to their ancestral lands.

President Bolsonaro is turning back the clock on indigenous rights, attempting to: erase their right to self-determination; sell off their territories to logging and mining companies; and ‘assimilate’ them against their will. Survival International and tribal peoples are fighting side by side to stop Brazil’s genocide.

Fiona Watson of Survival International said today: “The history of the Xokleng shows just how absurd the “Time Limit Trick” is: Indigenous peoples have been evicted from their lands, hunted down and murdered in Brazil for centuries. Those who demand that in order to have the right to their land now, indigenous lands had to have been inhabited by indigenous communities on October 5, 1988 – after the end of the military dictatorship – are denying this history and perpetuating the genocide in the 21st century.”

Note to the editor:

– More information on the Xokleng and their history can be found here.

– The case before the Court concerns only the Xokleng of Ibirama La Klãnõ indigenous territory. There are many other Xokleng communities.