by DGR News Service | Mar 8, 2021 | Education, Movement Building & Support, Repression at Home, Strategy & Analysis

In this article Max Wilbert outlines the political and environmental need for security culture. He offers recommendations to secure communications.

By Max Wilbert

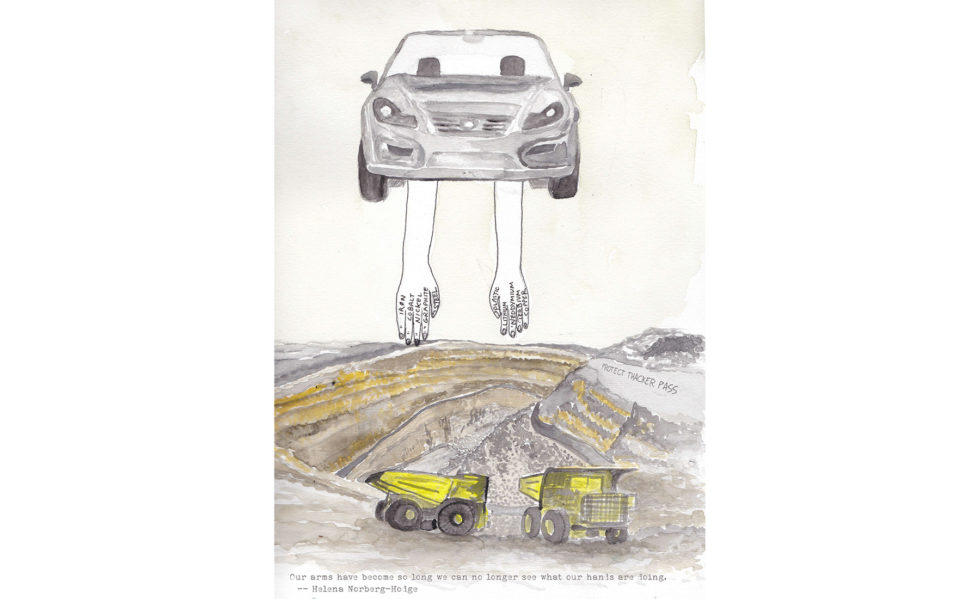

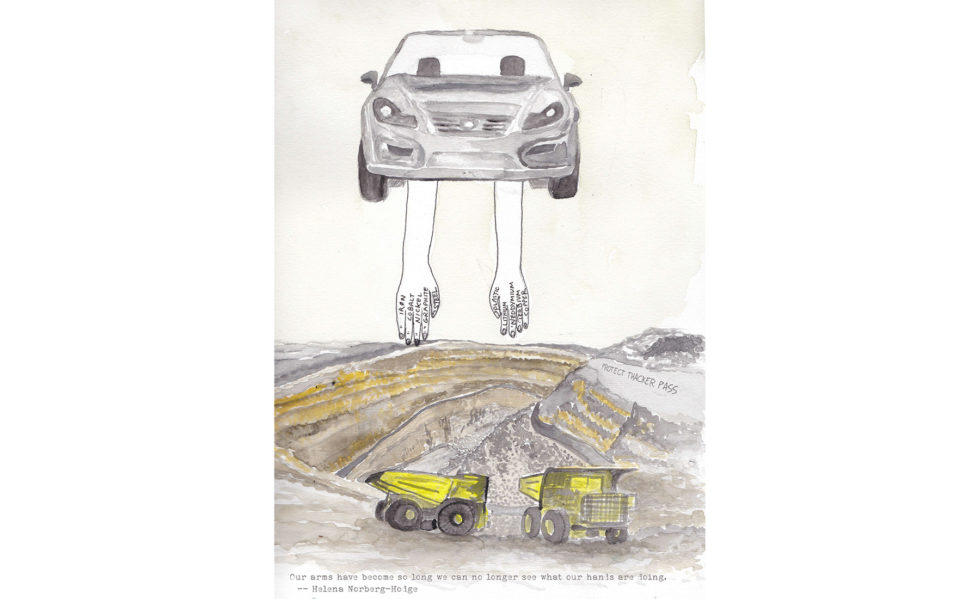

For 50 days, the Protect Thacker Pass camp has stood here in the mountains of northern Nevada, on Northern Paiute territory, to defend the land against a strip mine.

Lithium Americas, a Canadian corporation, means to blow up, bulldoze, or pave 5,700 acres of this wild, biodiverse land to extract lithium for “green” electric cars. In the process, they will suck up billions of gallons of water, import tons and tons of waste from oil refineries to be turned into sulfuric acid, burn 11,000 gallons of diesel fuel per day, toxify groundwater with arsenic, antimony, and uranium, harm wildlife from Golden eagles and Pronghorn antelope to Greater sage-grouse and the endemic King’s River pyrg, and lay waste to traditional territories still used by people from the Fort McDermitt reservation and the local ranching and farming communities.

The Campaign to Protect Thacker Pass

They claim this is an “environmentally sustainable” project. We disagree, and we mean to stop them from destroying this place.

Thus far, our work has been focused on outreach and spreading the word. For the first two weeks, there were only two of us here. Now word has begun to spread. The campaign is entering a new stage. There are new opportunities opening, but we must be cautious.

How Corporations Disrupt Grassroots Resistance Movements

Corporations, faced with grassroots resistance, follow a certain playbook. We can look at the history of how these companies respond to determine their strategies and the best ways to counteract them.

Corporations like Lithium Americas Corporation generally do not have in-house security teams, beyond basic security for facilities and IT/digital security. Therefore, when faced with growing grassroots resistance, their first move will be to hire an outside corporation to conduct surveillance, intelligence gathering, and offensive operations.

Private Military Corporations (PMCs) are essentially mercenaries acting largely outside of government regulation or democratic control. They are hired by private corporations to assist in their interests and act as for-hire businesses with few or no ethical considerations. Some examples of these corporations are TigerSwan, Triple Canopy, and STRATFOR.

PMCs are often staffed with U.S. military veterans, and employ counterinsurgency techniques and skills honed during the invasions of Iraq and Afghanistan, or other military operations. And in many cases, these PMCs collaborate with public law enforcement agencies to share information, such that law enforcement is essentially acting as a private contractor for a corporation.

Disruption Tactics Used by Corporate Goon Squads

PMCs can be expected to deploy four basic tactics.

- Intelligence Gathering

First, they will attempt to gather as much information on protesters as possible. This begins with what is called OSINT — Open Source Intelligence. This simply means combing through open records on the internet: Googling names, scrolling through social media profiles and groups, and compiling information that is publicly available for anyone who cares to look.

Other methods of information gathering are more active, and include physical surveillance (such as flying a helicopter overhead, as occurred today), signals intelligence (attempting to capture cell phone calls, emails, texts, and website traffic using a device like a Stingray also known as an IMSI catcher), and infiltration or human intelligence (HUMINT). This last is perhaps the most important, the most dangerous, and the most difficult to combat.

- Disruption

Second, they will attempt to disrupt the protest. This is often done by using the classic tactics of COINTELPRO to plant rumors, false information, and foment infighting to weaken opposition.

During the protests against the Dakota Access Pipeline, one TigerSwan infiltrator working inside the protest camps wrote to his team that

“I need you guys to start looking at the activists in your area and see if there are individuals who are vulnerable. They’re broke, always talking about needing gas money or whatever. Maybe they’re disillusioned, depressed a little. Life is fucking them over. We can buy them a bus ticket to any camp they want if they’re willing to provide intel. We win no matter what. If they agree to inform for pay, we get intel. If they tell our pitchman to go f*** himself/herself, the activist will start wondering who did take the money and it’ll cause conflict within the activist groups and it won’t cost us anything.”

In 2013, there was a leak of documents from the private intelligence company STRATFOR, which has worked for the American Petroleum Institute, Dow Chemical, Northrup Grumman, Coca Cola, and so on. The leaked documents revealed one part of STRATFOR’s strategy for fighting social movements. The document proposes dividing activists into four groups, then exploiting their differences to fracture movements.

“Radicals, idealists, realists and opportunists [are the four categories],” the leaked documents state. “The Opportunists are in it for themselves and can be pulled away for their own self-interest. The Realists can be convinced that transformative change is not possible and we must settle for what is possible. Idealists can be convinced they have the facts wrong and pulled to the Realist camp. Radicals, who see the system as corrupt and needing transformation, need to be isolated and discredited, using false charges to assassinate their character is a common tactic.”

As I will discuss later on, solidarity and movement culture is the best way to push back against these methods.

Other examples of infiltration and disruption have often focused on:

- Increasing tensions around racist or sexist behavior

- Targeting individuals with drug or alcohol addictions to become informants

- Using sex appeal and relationship building to get information

- Acting as an “agent provocateur” to encourage protesters to become violent, even to the point of supplying them with bombs, in order to secure arrests

- Spreading rumors about inappropriate behavior to sew discord and mistrust

- Intimidation

The third tactic used by these companies is intimidation. They will use fear and paranoia as a deliberate form of psychological warfare. This can include anonymous threats, shows of force, visible surveillance, and so on.

- Violence

When other methods fail, PMCs and public law enforcement will ultimately resort to direct violence, as we have seen with Standing Rock and many other protest movements.

As I have written before, colonial states enforce their resource extraction regimes with force, and we should disabuse ourselves of notions to the contrary. Vigilante violence is also always a concern. When people seek to defend land from destruction, men with guns are usually dispatched to arrest them, remove them from the site, and lock them in cages.

How to Resist Against Surveillance and Repression

There are specific techniques we can deploy to protect ourselves, and by extension, protect the land at Thacker Pass. These techniques are called “security culture.”

Security culture is a set of practices and attitudes designed to increase the safety of political communities. These guidelines are created based on recent and historic state repression, and help to reduce paranoia and increase effectiveness.

Security culture cannot keep us 100% safe, all the time. There is risk in political action. But it helps us manage risks that do exist, and take calculated risks when necessary to achieve our goals.

The first rule of security culture is this: be cautious, but do not live in fear. We cannot let their intimidation be effective. Creating paranoia is a key goal for PMCs and other repressive organizations. When they make us so paranoid we no longer take action, reach out to potential allies, or plan and carry out our campaigns, they win using only the techniques of psychological warfare. When we are fighting to protect the land and water, we are doing something righteous, and we should be proud and stand tall while we do this work.

The second rule of security culture is that solidarity is how we overcome paranoia, snitchjacketing, and rumor-spreading. We must act with principles and in a deeply ethical and honorable way. Work to build alliances, friendships, and trust—while maintaining good boundaries and holding people accountable. This is the foundation of a good culture.

In regards to infiltration, security culture recommends the following:

- It’s not safe nor a good idea to generally speculate or accuse people of being infiltrators. This is a typical tactic that infiltrators use to shut movements down.

- Paranoia can cause destructive behavior.

- Making false/uncertain accusations is dangerous: this is called “bad-jacketing” or “snitch-jacketing.”

- Build relationships deliberately, and build trust slowly. Do not share sensitive information with people who don’t need to know it. There is a fine line between promoting a campaign and sharing information that could put someone at risk.

- Good security culture focuses on identifying and stopping bad behavior.

- Do not talk to police or law enforcement unless you are a designated liaison.

Secure communications are an important part of security culture.

Here are some basic recommendations to secure your communications.

- Email, phone calls, social media, and text messages are inherently insecure. Nothing sensitive should be discussed using these platforms.

- Preferably, use modern secure messaging apps such as Signal, Wire, or Session. These apps are free and easy to use.

- We recommend setting up and using a VPN for all your internet access needs at camp. ProtonVPN and Firefox VPN are two reputable providers. These tools are easy to use after a brief initial setup, and only cost a small amount. Invest in security.

We must also remember that secure communications aren’t a magic bullet. If you’re communicating with someone who decides to share your private message, it’s no longer private. Use common sense and consider trust when using secure communications tools.

Security culture also warns us not talk about some sensitive issues, including:

- Your or someone else’s participation in illegal action.

- Someone else’s advocacy for such actions.

- Your or someone else’s plans for a future illegal action.

- Don’t talk about illegal actions in terms of specific times, people, places, etc.

Note: Nonviolent civil disobedience is illegal, but can sometimes be discussed openly. In general, the specifics of nonviolent civil disobedience should be discussed only with people who will be involved in the action or those doing support work for them. It’s still acceptable (even encouraged) to speak out generally in support of monkeywrenching and all forms of resistance as long as you don’t mention specific places, people, times, etc.

Conclusion

Security is a very important topic, but is challenging. There are so many potential threats, and we are not used to acting in a secure way. That’s why we are working to create a “security culture”—so that our communities of resistance are always considering security, assessing threats, studying our opposition, and creating countermeasures to their methods.

This article is only a brief introduction to the topic of security culture. Moving forward, we will be providing regular trainings in security culture to Protect Thacker Pass participants.

Most importantly, do not let this scare you, and do not be overwhelmed. Simply take one security measure at a time, begin to study it, and then implement better protocols one by one. We use the term “security culture” because security is a mindset that should be developed and shared.

Resources:

Recommended topics of study:

by DGR News Service | Mar 6, 2021 | Male Supremacy, Male Violence, Movement Building & Support, Pornography, Prostitution, Rape Culture, The Problem: Civilization, Women & Radical Feminism

In Part One of a two part article Jocelyn Crawley offers the reader a history and systemic analysis of the harms towards women. Part two will be published the following day.

When I first discovered how widespread acceptance of and/or compliance towards rape, pornography, pedophilia, prostitution, and sex trafficking are, I was enraged. I once viewed a documentary indicating that pimps systematically show little girls videos of women performing fellatio on men to “educate” them on how to provide this “service” to the males they are trafficked to. One thought I had while attempting to process what was transpiring was: this is crazy. In addition to drawing this conclusion, I was filled with unalloyed shock and deep ire. I then reconceptualized the prototypical way I interpreted reality (men and women coexist together in a state of relative peace marked by periodic hiccups, spats, “trouble in paradise,” etc.) and came to understand that patriarchy is the ruling religion of the planet with women being reduced to the subordinated class that men systematically subjugate and subject to a wide range of oppressions.

Part of patriarchy’s power is making its perverse rules and regulations for how reality should unfold appear normative and natural while categorizing anyone who challenges these perversions as insane. Insanity is defined as a state of consciousness confluent with mental illness, foolishness, or irrationality. According to patriarchal logic, any individual who attempts to question or quell its nefarious, necrotic systems and regimes is thinking and acting in an illogical manner. To express the same concept with new language to further elucidate this component of material reality under phallocracy: anyone who does not accept patriarchal logic is illogical or insane according to patriarchal logic. For this reason, it is not uncommon for women who challenge men who sexually harass or intimidate them into sex trafficking to be called insane. It is critically important for radical feminists to examine and explore this facet of the patriarchy in order to gain more knowledge about how phallocentrism works and what can and should be done to abrogate and annihilate it.

To fully understand the integral role that accusing women of being insane plays in normative patriarchal society, one should first consider the etymology of the word.

As noted in “Stop Telling Women They’re Crazy” by Amber Madison, the term hysteria entered cultural consciousness “when people didn’t want to pay attention to a woman” . When this happened, the woman was oftentimes taken to a medical facility and was subsequently diagnosed with hysteria. The phrase “hysteria” was an umbrella term meant to reference women who “caused trouble,” experienced irritability or nervousness, or didn’t reflect the level of interest in sexual activity deemed appropriate by men. The word hysteria is derived from the Greek term “hystera,” which means uterus. Thus the etymological history of the word informs us of the attempt to conflate the psychobiological experience of insanity with the material reality of being a biological female.

In recognizing the role that patriarchal societies play in attempting to establish confluence between insanity and the material reality of being a woman, it is important to note that individuals who take the time to carefully scrutinize patriarchy are cognizant of the male attempt to make mental instability a fundamentally female flaw. For example, Elaine Showalter has noted that the primary cultural stereotype of madness construed the condition as a female malady (Showalter, 1985, as cited in MacDonald, 1986). As noted by Julianna Little in her thesis “Frailty, thy name is woman: Depictions of Female Madness,”

“The most significant of cultural constructions that shape our view of madness is gender. Madness has been perceived for centuries metaphorically and symbolically as a feminine illness and continues to be gendered into the twenty-first century” (5).

In the twenty-first century, individuals who have wished to challenge the notion that the thoughts and emotions experienced by women are automatically and inevitably signs of insanity utilize the term “gaslighting” to refer to this insidious mindfuckery.

The history of men accusing women of being insane in response to accusations of sexual abuse is well-documented.

One significant case which should be a part of public consciousness is that of Alice Christiana Abbott. Abbott poisoned her stepfather in 1867 and, upon being questioned, stated that he had had an “improper connection” with her since she was thirteen. After informing others of this, the majority believed that “something was the matter with her head.” However, there was nothing wrong with her head. In fact, I argue that she operated according to a rightness of mind which recognized sexual assault as fundamentally wrong. Abbott’s stepfather threatened to have her put in reform school if she spoke of the abuse, and this was the assertion that prompted her to act. When her case took place in the Suffolk County Grand Jury, Abbott was committed to the Taunton Lunatic Asylum (Carlisle, “What Made Lizzie Borden Kill?”) That the sentence for challenging a man who sexually abuses a woman incorporates classifying her as insane indicates the patriarchy’s ongoing attempt to construe its malevolent, depraved rules and regulations (which include normalizing and in some cases valorizing the sexual abuse of women) as natural and appropriate.

(The historical reality of men accusing women of being insane and utilizing the assertion to severely limit their life choices and thereby sustain patriarchy is not limited to issues of sexual abuse. In fact, men have appropriated the accusation of female insanity against women who committed any acts which challenged their power. This fact becomes plain when one considers the case of Elizabeth Parsons Ware Packard. Packard married Theophilus Packard and experienced ideological disparities with him pertaining to religious philosophy. Specifically, Packard began demonstrating interest in the spiritual ideologies of perfectionism and spiritualism (Hartog, 79).

Perfectionism is a thought system advocating the notion that individuals could become sin-free through will power and conversion. Packard also assented to the notion of spiritualism, with this religious movement promoting the idea that the souls or spirits of dead individuals continued to exist and were also capable of communicating with living people. Theophilus Packard maintained conservative religious views that stood in diametric opposition to the aforementioned ideologies, with his own perspective including the notion of innate human depravity. After Elizabeth Packard began openly questioning his ideas and exploring her own, their ideological dissonance led to his accusation that she was insane. The accusation was officially made in 1860 and Packard decided to have his wife committed. Elizabeth Packard learned of his decision on June 18, 1860. It’s important to note that the patriarchal nature of this scenario is not limited to the interactions and ideological disparities existing between Elizabeth Packard and Theophilus Packard as two individuals. In fact, state law revealed its own patriarchal proclivity for privileging male interpretations of reality for the purpose of disempowering and dehumanizing women. This is the case as when, in 1851, the state of Illinois opened its first hospital for those who were allegedly mentally ill, the legislature passed a law which enabled husbands to have their wives committed without their consent or a public hearing.)

To be continued . . .

Jocelyn Crawley is a radical feminist who resides in Atlanta, Georgia. Her intense antagonism towards all forms of social injustice-including white supremacy-grows with each passing day. Her primary goal for 2020 is to connect with other radicals for the purpose of building community and organizing against oppression.

Works Cited

Carlisle, Marcia R. “What Made Lizzie Borden Kill?” https://www.americanheritage.com/what-made-lizzie-borden-kill#2. Accessed 20 Feb. 2021.

Hendrik Hartog, Mrs. Packard on Dependency, 1 Yale J.L. & Human. (1989). Available at: https://digitalcommons.law.yale.edu/yjlh/vol1/iss1/6.

Human Rights Watch. Booted: Lack of Recourse for Wrongfully Discharged US Military Rape Survivors.https://www.hrw.org/report/2016/05/19/booted/lack-recourse-wrongfully-discharged-us-military-rape-survivors#. Accessed 20 Feb. 2021

Macdonald, Michael. “Women and Madness in Tudor and Stuart England.” Social Research, vol. 53, no. 2, 1986, pp. 261–281. JSTOR, www.jstor.org/stable/40970416. Accessed 20 Feb. 2021.

Madison, Amber. “Stop Telling Women They’re Crazy.” https://www.refinery29.com/en-us/2014/09/75146/stop-women-crazy-emotions-gender. Accessed 20 Feb. 2021.

Marcotte, Amanda. ““Price of calling women crazy: Military women who speak out about sexual assault are being branded with “personality disorder” and let go.” https://www.salon.com/2016/05/20/price_of_calling_women_crazy_military_women_who_speak_out_about_sexual_assault_are_being_branded_with_personality_disorder_and_let_go/. Accessed 20 Feb. 2021.

Showalter, Elaine. The Female Malady: Women, Madness, and English Culture, 1830-1980 (New York: Pantheon, 1985). quoted in Macdonald, Michael. “Women and Madness in Tudor and Stuart England.” Social Research, vol. 53, no. 2, 1986, pp. 261–281. JSTOR, www.jstor.org/stable/40970416. Accessed 20 Feb. 2021.

Wright, Jennifer. “Women Aren’t Crazy.” https://www.harpersbazaar.com/culture/politics/a14504503/women-arent-crazy/. Accessed 20 Feb. 2021.

by DGR News Service | Mar 5, 2021 | Biodiversity & Habitat Destruction, Colonialism & Conquest, Indigenous Autonomy, Mining & Drilling, Movement Building & Support, The Problem: Civilization

Editor’s note: DGR stands in strong solidarity with indigenous peoples worldwide. We acknowledge that they are victims of the largest genocide in human history, which is ongoing. Wherever indigenous cultures have not been completely destroyed or assimilated, they stand as relentless defenders of the landbases and natural communities which are there ancestral homes. They also provide living proof that not humans as a species are inherently destructive, but the societal structure based on large scale monoculture, endless energy consumption, accumulation of wealth and power for a few elites, human supremacy and patriarchy we call civilization.

By Boris Wu

On Thursday, January 14th 2021, 46 people belonging to the ethnic minority of the Pygmies were killed by suspected rebels of the Allied Democratic Forces (ADF). The massacre happened in the village of Masini, Badibongo Siya group, chiefdom of Walese Vonkutu in the territory of Irumu, province of Ituri.

The murders were committed by men armed with machetes and firearms. According to the coordinator of the French NGO CRDH (C.R.D.H./Paris Human Rights Center), the men were identified “as Banyabwisha disguised as ADF / NALU rebels”. Many of the bodies have been mutilated. Two people, a woman and a child of about two years, have been injured although escaped the attack. The surviving woman identified the attackers as Banyabwisha.

Adjio Gidi, minister of the interior and security of the province, confirmed the information about the massacre, but rather attributes this attack to real ADF / NALU rebels. The Allied Democratic Forces (ADF) is an Ungandan armed group that is suspected to have carried out a series of massacres in eastern Congo, according to U.N. figures killing more than 1,000 civilians since the start of 2019.

The eastern borderlands of the Democratic Republic Congo with Uganda, Rwanda and Burundi are home to over 100 different constellations of militias, many of them remnants of the brutal civil war that officially ended 2003. The Islamic State has claimed responsibility for many suspected ADF attacks in the past, but so far, according the U.N., there is no confirmation of a direct link between the two groups.

Continued Violence

Violent conflicts between the ethnic minority of the indigenous Pygmies and the ethnic majority of the Bantu, which includes several ethnic groups like the Luba, have been going on for centuries. The Pygmies in the Congo are semi-nomadic hunter-gatherers, traditionally living in dense forests. The Luba live in neighboring towns and villages, largely making a living by trade and commerce. The pygmies have been discriminated for a long time by different ethnic groups of the Bantu majority. This includes forcing them to leave their ancestral lands, which are rapidly being destroyed by deforestation.

More recently, pressure and violence towards the Pygmies has been rising due to the government setting up national parks in areas that are the ancestral home of the pygmies, such as the Kahuzi-Biega National Park. This situation leads to increasingly violent conflicts between Pygmies and park guards. Foreign companies operating in this region fuel further (often violent) conflict by exploiting the countries natural resources with logging operations, mining concessions and carving out farm plots.

The pygmies, making up less than 1% of Congo’s population (with the Luba making up about 18% and the overall Bantu-majority about 80%) want to be represented by quotas in government. They have been victims of racial discrimination for a long time, even categorized as “sub-human” by the Belgians who colonized this area.

The atrocities towards these indigenous peoples must stop.

Our members of DGR Africa are documenting and speaking out about the ongoing violence in the region.

You can support our ally and DGR community in The Congo in their indigenous community forestry program. Donate to CAPITA ASBL via Bank Transfer to:

*00031-26720-60030080011-86

USD, Intitulé CAPITA ASBL V/C USD*

Sources:

Featured image: Pygmy settlement in the rainforest

JMGRACIA100, CC BY-SA 4.0 via Wikimedia Commons

- Report by Rossy, DGR Africa (personal communication)

- Forty-six civilians feared killed in eastern Congo attack, official says

- Kahuzi-Biega National Park – RFI

- Dozens massacred, bodies mutilated in DR Congo ethnic clashes

by DGR News Service | Mar 3, 2021 | Agriculture, Direct Action, Movement Building & Support, Worker Exploitation, Worker Solidarity

Written by Manu Moudgil – India’s historic farmers movement has overcome regional, religious, gender and ideological differences to challenge corporate influence on government.

By Manu Moudgil/Waging Non Violence

On Feb. 6, protesters blocked roads at an estimated 10,000 spots across India as part of the ongoing movement against the new farm laws enacted by the national government last year. For over two months, the most populous democracy in the world has witnessed what is being called one of the biggest protests in human history.

Hundreds of thousands of farmers have been rallying against three new laws that have thrown open the agriculture sector to private players. Protesters feel the legislation will allow a corporate takeover of crop production and trading, which would eventually impact their earnings and land ownership. They are camping on the roads connecting the national capital with major north Indian cities, braving harsh winters and smear campaigns from the mainstream media and ruling party supporters. Over 224 protesters have already lost their lives for various reasons, chief among them camping outdoors in the frigid weather.

The movement has overcome regional, religious, gender and ideological differences to build pressure.

Leftist farm unions, religious organizations and traditional caste-based brotherhoods called khaps, which make pronouncements on social issues, are working in tandem through resolute sit-ins and an aggressive boycott of politicians.

“We believe the laws have been framed at the direction of the private sector to directly benefit them. So, the protests have to target big businesses along with the government,”

said Jagmohan Singh, president of one of the farm unions representing protesting farmers. India’s right-wing government led by Prime Minister Narendra Modi of the Bharatiya Janata Party, or BJP, pushed the laws through the parliament in September, despite lacking a majority in the upper house and agriculture being in the jurisdiction of state governments. The protest is a response to the lack of respect for parliamentary democracy and federalism, but its main focus is the pervasive corporate influence on governance.

After limits on corporate contributions were removed and allowed to be made anonymously, $8.2 billion was spent on Indian parliamentary elections in 2019, which exceeded how much was spent on the U.S. election in 2016 by 26 percent. Most of this money came from corporations and the BJP was the primary recipient.

The political-corporate influence is also jeopardizing media’s independence in the country. India ranks 142nd out of 180 countries in the World Press Freedom Index. Mainstream TV news channels often eulogize the government and Hindu right-wing ideology and smear voices of dissent and minorities. Farmers and their supporters have responded by boycotting media outlets, starting their own newsletters and promoting independent journalism. The movement has already received global attention on social media, with climate activist Greta Thunberg and pop star Rihana recently extending support to the protesters.

Farm crisis is the fuel

Farmers are a large electoral block in India, with half the population being engaged in agriculture. No political party can afford to offend them publicly even though policy makers have done little to increase farm incomes and address their indebtedness. Around 300,000 farmers died by suicide between 1995 and 2013, mostly due to financial stress. In 2019, another 10,281 farmers took their lives.

The Modi government came to power in 2014 on the promise of doubling farmer’s income. It claims the new laws will help fulfill that pledge by allowing for the sale of produce and contract farming outside the purview of state governments and remove of cap on stockholding of food items. Farmers, however, are not buying these arguments.

“The laws are tilted against the farmers and give a free hand to private companies by removing the safeguard of state market committees, which usually intervene in case of disputes with traders,” said Gurtej Singh, a farmer from Punjab. “The committee members are easily accessible even to small farmers, compared to the courts or district officials, which the new laws propose as regulatory authorities.”

Indian farms are mostly family-owned and land is a source of subsistence for millions. Around 86 percent of farmers, however, till less than five acres while the other 14 percent, mostly upper castes, own over half of the country’s 388 million acres of arable land.

Now they fear that the new laws will dismantle the government support system as well and further push them into poverty. “Laws are just the imminent trigger. The protest is actually a manifestation of anger about the constant decline in farming as a profitable occupation over the last few decades,” Singh said. “We have mostly been handed short term relief around election times.”Farmers in a few north Indian states were able to consolidate their holdings through increased incomes with the introduction of irrigation, modern seeds, fertilizers, machines, market infrastructure and guaranteed price support from the government during the Green Revolution in the 1960s. But rising input costs and climate crisis have adversely impacted the profits there as well. In Punjab, the most agriculturally-developed state, for instance, the input costs of electric motors, labor, fertilizer and fuel rose by 100 to 290 percent from 2000 to 2013, but the support price of wheat and rice rose by only 122 to 137 percent in the same period, according to a government report. Heavy use of chemicals, mono-cropping and farm mechanization have damaged the soil, affecting productivity and forcing farmers into debt.

The new farm laws were enacted at a time when India had yet to recover from one of the most punitive lockdowns in the world imposed in the wake of the COVID-19 pandemic, which prevented large gatherings. However, the government lost the battle of perceptions from the very start. Since farming is the largest avenue of self-employment and subsistence in India, throwing the sector open to private players was bound to kindle fears that owners would lose autonomy over their lands.

Strength and strategy

Punjab saw widespread protests as soon as the laws were enacted. Farmers occupied railway tracks and toll plazas on major roads besides corporate-owned thermal plants, gas stations and shopping malls. Scores of subscribers left Jio, the telecom service owned by the top Indian businessman perceived to be close to Prime Minister Modi.

Farm unions also held regular sit-ins in front of the houses of prominent political leaders forcing an important regional party to leave the national government alliance. Several state leaders of the ruling party resigned from their posts as well. Similar scenes played out in the neighboring state of Haryana, where leaders were publicly shamed and the helicopter of the elected head of the government was prevented from landing for a public meeting after farmers dug up the helipad area.

In November, thousands of farmers drove their tractor trolleys towards the national capital as they played protest songs by celebrity singers. Stocked with rations, clothing, water and wood for months, they braved tear gas shells and water cannons used by the police along the way. Powerful tractors pushed heavy transport vehicles, concrete slabs and barbed wires that the administration had placed en route out of their way.

Stopping at the northern and western borders of New Delhi, the long cavalcades of tractor trolleys turned into encampments, and numerous community kitchens sprang up. Residents of nearby villages and towns chipped in by supplying milk and vegetables, and offering bathrooms in their houses, shops, gas stations and offices for use by protesters.

Open libraries and medical camps were set up and volunteers offered their skills, ranging from tailoring to tutoring children. Besides speeches by the farm leaders, cultural performances, film screenings and wrestling bouts became a regular feature. More farmers poured in with each passing day. Indians in the diaspora gave donations to farm unions and village councils, which offered money for fuel and other expenses to villagers who could not afford to visit the protest sites on their own. The resistance to the corporatization of agriculture has penetrated deep.

“These occupations are not just a reaction of wronged citizens who have set out to reform the Indian parliament or assert dissent. Rather, they form an important stage in a still-unfolding narrative of militant anti-capitalist struggle,”

wrote Aditya Bahl, a doctoral scholar at the John Hopkins University who is archiving the peasants’ revolts that took place in Punjab in the 1960s and ’70s.

The protests are not only targeting domestic companies and political figures.

Farmers have also burnt effigies of Uncle Sam, the World Trade Organization and IMF, signifying the influence of global trade over domestic agricultural policies. Developed countries have been pressuring India for last three decades to open up its agriculture sector to multinational players by slashing subsidies and reducing public procurement and distribution of food grains to the poor.The Indian Supreme Court suspended the implementation of laws and formed a four-member expert committee on Jan. 13 to look into the issue. Farmers have, however, refused to meet the committee members, alleging that many of them have already written or spoken in favor of the laws.

“Agricultural reforms and free markets have failed to help American farmers who are dying by suicide due to heavy debts,” explained food and trade policy expert Devinder Sharma. “Their farm incomes are in the negative, even though they have big landholdings and billions of dollars of income support from the government. How can the same model work for India, especially when it’s not even designed for our domestic conditions?”

Protesters are also seeking a legal right to sell their produce at a guaranteed price. The Indian government usually declares a minimum support price on various crops based on costs of their production, but only a fraction of the produce is procured at that rate. In the absence of government procurement facilities in their areas, most farmers have to settle for a lower price offered by private traders. A law would make it mandatory for private players to buy the produce at a declared price.

“If Indian farmers are able to get the law on guaranteed price passed through their current agitation, they will become a role model for farmers across the world living under heavy debts,” Sharma continued. “India should put its foot down at the WTO and create much-needed disruption in the world food trade policy for the benefit of the global agriculture sector.”

The movement grows

The BJP-led national government has faced numerous protests over the last six years of its rule, including by university students, workers and caste and religious minorities. With the help of media and security agencies, however, the government has always been able to frame dissent as being unpatriotic. The country has dropped 26 places in the Democracy Index’s global ranking since 2014 due to “erosion of civil liberties.”

This is the first time peasants have been galvanized in such large numbers against the government. The government has already held 11 rounds of negotiations with farmers’ representatives and offered to suspend the laws for one and a half years on Jan. 20. But farmers are not budging from their demand of the complete repeal of the laws and legal cover for the selling of their crops at a guaranteed price. The movement, initiated by Punjab’s farmers, has taken on a national character. On Jan. 26, which marks India’s Republic Day, 19 out of 28 states witnessed protests against the farm laws.

In Delhi, however, a plan to organize a farmers’ tractor march parallel to the official Republic Day function, went awry. A group of protesters clashed with police at multiple spots and stormed the iconic Red Fort, a traditional seat of power for the Mughals, where the colonial British and independent India’s prime ministers have also raised their flags.

The rural-urban divide became starker on the night of Jan. 27. While TV anchors and their captive urban audience smirked at visuals of a leader of the farmers’ movement crying as he faced imminent arrest, villages erupted in anger. Temple priests gave calls over public address systems, nightly meetings were arranged and thousands drove hundreds of miles through a foggy winter night to reach the protest site on eastern fringe of national capital New Delhi, compelling the administration to pull the police back and restart the water and power supply to the protest site.The protesters unfurled banners of the farm unions and Sikhs — one of the minority religious groups and the most prominent face of the protests. Mainstream media and ruling party supporters used the opportunity to blame the movement for desecration and religious terrorism. Security forces charged sleeping farmers with batons at one location, filed cases against movement leaders, allowed opponents to pelt campaigners with stones, arrested journalists and shut down the Internet.

The attacks, therefore, ended up lifting the flagging morale of the farmers and helped the movement gain even more supporters, who shunned the government and media narrative. Massive community gatherings of khaps were organized at multiple places over next few days, extending their support to the protests and issuing a boycott call for the BJP and its political allies.

Smear campaigns to depict Sikh farmers as terrorists, a reference to an armed movement in the 1980s and ’90s for a separate homeland, found no resonance beyond the right-wing echo chamber. Sikh protesters draw inspiration from the religious tenets of community service, equality and the fight against injustice. Community kitchens run by Sikh organizations have served through many humanitarian crisis, like the ongoing civil war in Syria and movements like Black Lives Matter. Sikhs in India have remained steadfastly egalitarian, ready to support other religious minorities in times of need.

Mending fault lines

The movement has also been able to overcome regional and gender divisions, and is trying to address caste divides. The states of Haryana and Punjab are often at loggerheads on the issue of sharing of river waters. Haryana was carved out of Punjab on linguistic lines in 1966, but most of the rivers flow through the current Punjab state. Haryana has been seeking a greater amount of water for use by its farmers, while Punjab’s farmers oppose the demand, citing reduced water flow in the rivers over the years. The current protests have united farmers for a common cause, helping them understand each other even though opponents have made attempts revive the water issue.

Women have also been participating in the protests in large numbers. They are either occupying roads on Delhi’s borders or managing homes and farms in the absence of men, while taking part in protest marches in villages.

“Earlier, we were able to rally only 8,000-10,000 women for a protest. Today that number has swelled to 25,000-30,000, as they recognized the threats posed by the new laws to the livelihoods of their families,” said Harinder Bindu, who leads the women’s wing of the largest farm union in Punjab. “For many women this is the first time they are participating in a protest, which is a big change because they were earlier confined to household work. Men are getting used to seeing women participate and recognizing the value they bring to a movement.”

The union first encouraged the male leaders to include the women in their families with the cause to set an example for other members as well. “This helped inculcate the habit of sharing responsibilities,” Bindu said. “When women members participate in sit-ins, men manage the house. I feel this movement will bring greater focus on women’s issues within the farming community — one of which is the need to support widows of farmers who died by suicide due to financial constraints.”

In Punjab, less than four percent of private farm land belongs to Dalits, the lowest caste in the traditional social hierarchy of India, even though they constitute 32 percent of the state’s population. They often earn their livelihoods through farm work or daily wage labor. Even though Dalits have a legal right to till village common land, attempts to assert that right often lead to violent clashes with upper caste landlords who want to keep it for themselves.

“It’s not easy to overcome caste barriers. The acceptance and understanding evident in the leaders of the farmers’ unions is yet to percolate among their cadre.”

Dalits are waging similar battles across India. Researchers recorded 31 land conflicts involving 92,000 Dalits in 2019. A few of the farmers’ unions have supported and raised funds for Dalit agitations in the past. This has ensured the participation of farm workers in the current movement, but it has largely remained a farmers’ campaign.

“Dalits do understand that the new laws will impact them. Initially some of the workers did join the protests but they can’t afford to lose daily wages and also lack resources to travel long distance,” said Gurmukh Singh, a social activist working with Dalits to claim their right to cultivate village common land in Punjab. “But it’s not easy to overcome caste barriers. The acceptance and understanding evident in the leaders of the farmers’ unions is yet to percolate among their cadre.”

The movement is gradually encompassing other rural issues beyond the farm laws. In the state of Maharashtra, for instance, thousands of tribal people traveled to the capital Mumbai on Jan. 23 to extend support to the farmers. They also asserted their own long pending demand for land titles under the Forest Rights Act, which recognizes traditional rights of scheduled tribes and other forest dwellers on the use of land and other forest resources.

Starting from Punjab, the epicenter of protests has now extended to Uttar Pradesh, the most populous state of India, and leaders are planning to muster more support from central India.

The persistent protests also forced the government to hold an extensive debate on the issue in the parliament at the beginning of February, even though it did not lead to any resolution. The UK parliament may also consider debating the farmers’ protests and press freedom in India after an online petition on its website gathered the required number of signatures. Farmers’ leaders, meanwhile, have reaffirmed their stand to stay put on the roads for the long haul and have now decided to block railway tracks across the country for four hours on Feb. 18.

This article was first published in wagingnonviolence.org on February 16, 2021, you can read the original here

Manu Moudgil is an independent journalist based in India. He tweets at @manumoudgil

by DGR News Service | Feb 24, 2021 | Agriculture, Movement Building & Support, Protests & Symbolic Acts, Repression at Home

This article was written by Sarang Narasimhaiah and Mukesh Kulriya and published on Roarmag.org in the 5th February 2021. Sarang and Mukesh offer the reader a detailed account of the protests, why people are against corporate rule and what the protests may lead to.

Featured image by Mukesh Kulriya.

Amidst the months-long, farmer-led protests on the outskirts of Delhi, the foundations of a more democratic and anti-corporate India are being built.

On January 26, 2021, India observed its 71st Republic Day under historically unprecedented circumstances. On an occasion meant to commemorate the adoption of the Indian Constitution, two fiercely antagonistic visions of the country locked horns with each other in the capital of Delhi.

On the Rajpath ceremonial boulevard in the heart of Delhi, Prime Minister Narendra Modi and the ruling Bharatiya Janata Party (BJP)’s homegrown Hindu nationalist proto-fascism was on full display. It was no coincidence, for example, that the winner of the Republic Day Parade’s tableaux competition was the state of Uttar Pradesh, whose float celebrated the demolition of the Babri Mosque in 1992 and its impending replacement by a Hindu temple — a blood-soaked, decades-long travesty that has dovetailed with the rapid proliferation of the Hindu right.

In other parts of Delhi, however, a rather different spectacle was unfolding, as tens of thousands of farmers, primarily from the neighboring states of Punjab and Haryana, took over the streets of the city with their tractors.

For the past two months, hundreds of thousands of farmers have camped out on the outskirts of Delhi to protest three recently passed, transparently pro-corporate agricultural laws that stand to devastate their livelihoods. Coordinated by the Samyuta Kisan Morcha (United Farmers’ Front or SKM), the participants in the January 26 rally attempted to proceed along three pre-planned routes, but came up against police barricade after barricade. In the most explosive moment of the day, a section of the tractor parade broke away and entered the Red Fort, an iconic historical landmark in the heart of Delhi. Amidst gunfire, teargas, and lathi (baton) charges by state authorities, as well as a widely condemned internet shutdown, the protesters raised their own flags over a location famous for the prime minister’s hoisting of the Indian tricolor on Independence Day.

Notwithstanding predictable condemnations from India’s “law and order” liberals and leftists, the storming of the Red Fort and the Indian state’s hyper-repressive response exemplify how the protesting farmers have rocked Modi and the BJP to their core. They pose the most fundamental threat to the BJP’s neoliberal Hindu chauvinist agenda since Modi first came to power in 2014.

INDIA’S DESCENT INTO NEOLIBERAL HINDU NATIONALIST AUTHORITARIANISM

While the scale of the current resistance is unprecedented, the government’s targeting of vulnerable populations is not. Farmers are but the latest to appear in the cross hairs of the Modi government. Immediately after receiving a renewed mandate in India’s 2019 general election, Modi and the BJP stripped the majority Muslim region of Kashmir of its statehood, while simultaneously intensifying its brutal occupation by Indian military and paramilitary forces. This move came on the heels of the BJP-controlled northeastern state of Assam’s publication of a National Register of Citizens, which deliberately targeted Bengali-speaking Muslims, who are automatically presumed to be “illegal immigrants,” for detention. Finally, in December of 2019, India’s Parliament passed the Citizenship Amendment Act, which grants citizenship solely to non-Muslim refugees from Afghanistan, Bangladesh and Pakistan and could set the stage for rendering up to 200 million Indian Muslims stateless.

These measures — and the brutal repression of the mass protests that followed in their wake — demonstrate the Modi regime’s determination to lay the foundations for the ultimate goal of a Hindu supremacist ethnostate upheld by the Rashtriya Swayamsevak Sangh (National Volunteer Organization or RSS for short), the engine of the Hindu nationalist machine that was directly inspired by the Hitler Youth and Mussolini’s Black Brigades.

The social and cultural dimensions of the Hindu right’s authoritarianism underwrite its unabashedly neoliberal economic agenda. Modi rose to national prominence by implementing the “Gujarat Model” of politics in his home state, which essentially promotes economic growth by any and all means necessary, including extreme violence. Modi’s ruthlessness earned him the support of India’s foremost corporate dynasties, from the Tatas and the Ambanis to the Adanis. In exchange for bankrolling his political ascendancy, Modi has rewarded his corporate backers handsomely throughout his time in office: the annexation of Kashmir, for instance, has created a prime investment opportunity for Reliance Industries, the gargantuan conglomerate owned by India’s richest man, Mukesh Ambani.

In September of 2020, Modi and the BJP made perhaps their most profound corporate overture to date when they pushed through three agricultural bills that stand to “virtually kill the rights and entitlements of the agricultural population,” according to the Centre of Indian Trade Unions. As Peoples Dispatch explains, the Farmers’ Produce Trade and Commerce (Promotion and Facilitation) Bill, 2020 would prevent farmers from getting guaranteed prices for their crops by forcing them into an unregulated market space known as a “trade area.” Furthermore, the Essential Commodities Bill, 2020 would remove various items such as cereals, pulses, edible oils, onions and potatoes from the list of essential commodities, allowing large corporations to hoard these necessities.

Finally, the Farmers (Empowerment and Protection) Agreement of Price Assurance and Farm Services Bill, 2020 would allow for contract farming in India, which, given that 86 percent of India’s farmers own less than two hectares of land, would further shift the balance of agricultural power in favor of large corporations. Ambani’s Reliance Industries and the Adani Group of fellow billionaire industrialist Gautam Adani rank among the foremost prospective corporate beneficiaries of these bills.

LESSONS FROM THE FRONT LINE

Why have the aforementioned farm laws brought millions of protesters into the streets of Delhi and many other parts of India? How have farmers sustained their protest for over two months? How have the Indian and international media covered the farmers’ actions, and how have movement participants sought to combat misconceptions often propagated by this coverage? What are the deeper roots of the ongoing struggle? What do these protests mean for India and the wider world?

Seeking answers to these pressing questions, I spoke to Mukesh Kulriya, a third-year PhD student at the University of California, Los Angeles’ School of Music who has been on the front-lines of the farmer-led mobilization at the borders of Delhi since it first began. Mukesh is a longtime member of the All India Students Association (AISA), the collegiate wing of the Communist Party of India (Marxist-Leninist) Liberation.

Sarang Narasimhaiah: Could you describe the basis for the ongoing political action staged by farmers from Punjab, Haryana and other surrounding areas of Delhi, as well as so many other parts of the country?

Mukesh Kulriya: The immediate cause for this protest is that the Modi government passed three agricultural bills in a very undemocratic manner: these bills became laws under the cover of the COVID-19 pandemic, when the Indian Parliament was not even in session. The way the bills were passed was also unconstitutional: agriculture is a state matter in India, not a federal one, so how can the federal government rule on it? Moreover, even if you take a cursory look at these bills, you can see that they are totally pro-market. We need to remember that this government also carried out labor reforms that snatched away essential labor rights from organized sector workers, allowing them to be hired and fired as their employers please and placing their right to unionization under threat. The largest working population of the country — the workers and farmers who make up 80-90 percent of India’s workforce — have been hammered by both these sets of bills.

There was a lot of uproar when these laws were first proposed, and people quickly started to mobilize against them in Punjab. For a couple of months, they were organizing at the village level, but by the end of August and early September, protests started to erupt in cities across Punjab. What distinguished these protests was that they recognized the laws as a neoliberal attack on agriculture, and so they began to target the corporations responsible. The Adanis and Ambanis run the largest conglomerates in India: they are heavily invested in the privatization of agriculture and also very close to the current regime. As such, the slogans raised at the protests have opposed Prime Minister Modi but have also declared that he is nothing but a puppet in the hands of these corporations. This is not some academic writing a paper that criticizes neoliberalization: rather, corporations are being named and shamed by the common people. Farmers have shut down virtually all stores owned by the Adanis and Ambanis, hitting these corporations where it hurts. They have also taken out toll plazas across the state and refused to pay their toll taxes. In these ways, a mass popular movement has emerged addressing the questions of livelihood, land and labor: the classic issues of India’s feudal system [which continue to indelibly shape its capitalist present].

Corporations are being named and shamed by the common people.

On November 26, 2020, Indian laborers opposed to the above-mentioned labor reforms as well as the farm bills called for an all-India strike, and this was hugely successful. 250 million workers participated in that strike [making it the largest labor action in recorded human history]. On that same day, farmers from Punjab decided that they should march to Delhi. When they reached the borders of the city, they were stopped by the police and other government forces, who dug 15-meter wide holes in the road, put up ten layers of barricades and barbed wire, and used tear gas and lathi charges against the farmers.

When videos of these attacks showing the brutality of this government started to circulate, many people were moved to take action. The next day, more people from Punjab and Haryana started coming to the borders of Delhi, and the state couldn’t do anything to stop them. The farmers and their supporters wanted to occupy a central space in Delhi, but the government tried to force them into a remote corner of the city; the protesters refused to use this site and decided to block the city instead. Incredibly, by now, the capital of India has been blocked by protesters for almost two months. Some of these protests are almost 15 kilometers long; you can see one to two hundred thousand people at one protest site alone.

This protest is significant to no small extent because Punjab is one of India’s more well-off states, largely due to agriculture. Punjab has been suffering as a result of India’s agricultural crisis in a very different way from the rest of the country. Punjab was basically a laboratory for the Green Revolution in India, along with Haryana and Western Uttar Pradesh. This makes it the only agricultural belt in the country where small farmers have a little money. However, because of pesticides and other chemicals used in industrial farming, this area has also become a cancer belt. There is actually a train that goes from Punjab toward my hometown in Rajasthan which is known as the “Cancer Express.” People see the money that agriculture brought to Punjab, but not the cancer, the huge indebtedness and the institutionalized drug racket that has been very active in the state.

Punjab has a long revolutionary history; the powers that be know that this state could be dangerous to them, and so they have sought to undermine its people while pocketing the wealth it generates. For that reason, it’s incredible to see young people who have been demonized as drug addicts come to the protest to show that they can be much more. They aspire for a better life that does not involve going abroad but rather fighting for better conditions in their homeland. You’re seeing the revitalization of a radical political consciousness in Punjab, in terms of poetry, in terms of music, in terms of the whole culture of organizing.

It is important to recognize that this is a mass movement by people who are not the poorest of the poor in the sense that the state believes. The state is used to looking at the farmer as someone who is worn and torn, who is very poor, who is very hungry, who is spreading their arms towards the state for some sort of help. However, these farmers, who are suffering even though they are relatively well-off, are very much challenging that image.

What does the day-to-day business of organizing the protests look like? And why have these protests been so effective?

The protest sites are basically temporary cities: you can get everything you need here. The protesters are running langars [traditional Sikh food services], medical services and many other kinds of services by themselves: they take shifts, and they do the monetary and physical labor to provide these services. People have realized that, when you fight against one kind of oppression, you also come to see other kinds of oppression that you perpetuate, and this realization has shaped the sociocultural structure of the protests: men are now cooking food, and women are leading political actions. The protests have been led by elders who have experience with mass movements, and they are striving to share this experience with younger generations like mine, who are seeing something like this for the first time in our lives; we are shouldering the logistics of the movement, learning as we go. We are learning that you can only save democracy if you take to the streets; you cannot expect democracy to work if you are sitting in your living room.

Many of the protesters are from rural agrarian communities, and so their day starts very early — around 5:00 or 5:30 am. They start cooking food, have breakfast and then head to their protest site’s central stage at 9:00 or 9:30 am. Every day, around 10 to 20 people go on a 24-hour hunger strike across all protest sites. In the daytime, people come from different parts of the country — or the world — to give speeches and show their solidarity.

We are learning that you can only save democracy if you take to the streets; you cannot expect democracy to work if you are sitting in your living room.

Every day, there is a meeting of the All India Kisan [Farmer] Coordination Committee, which is comprised of 32 different organizations. This movement does not have a single leader but rather a collective leadership. That’s also why it is so strong: “ordinary” people are so invested in the movement that no one has been able to hijack it. The Coordination Committee itself has been very clear that this is a people’s movement: if its leaders make any wrong decisions or unjustifiable compromises, they know that they will be thrown out the very same day.

The protesters are also saying that they are not in a hurry. They want the government to scrap the three laws, and they won’t settle for anything less. The kind of patience that they have is not conducive to settlement: they know that this is a long, drawn-out fight, and they are prepared to stay here for at least six months. The protesters are thus energetic but they’re also at ease, in a way; they know that they can’t be agitated and sloganeering all the time.

How have you and your AISA comrades endeavored to support the protesters?

Libraries are a key part of the temporary towns established by the protests. AISA is running an initiative known as the Shaheed Bhagat Singh Library at four protest sites. We open our library in the morning and a lot of people, from young students to older people, stop by and engage us.

We also started a newsletter, The Trolley Times. This newsletter was spurred at the initiative of a handful of independent individuals, and it is not associated with any single political organization. We realized that all recent social movements have relied almost solely on social media. Younger protesters had actually stopped considering fields of engagement beyond social media. As I said earlier, the people who are the backbone of these protests came to Delhi from their villages two months ago. They have been keeping their grounds while living about 10 kilometers away from their nearest stage; they know their responsibilities to the protests, and they are not looking for the limelight. Concerned that no one would talk to these people — or even acknowledge their presence — we wanted to ensure that they have a very clear sense of what is happening in the movement. These are older people, and so they are more likely to read newspapers and newsletters.

From the very first day that we published The Trolley Times, we got an amazing response. The vast majority of the Indian media is pro-corporate and owned by the same companies that want to privatize agriculture; these media are also pro-state, and so they demonize protesters with their propaganda. People realized that, to take ownership of this movement, they need their own voice. That’s what The Trolley Times aims to be. Becoming hugely popular within a day or two, The Trolley Times got a lot of media coverage, and it actually set a trend: now, there are three to four newsletters made by and for the movement. The Trolley Times gives a platform to first-time protesters, young protesters, elderly protesters and single women protesters. To a barber who came here to give massages to tired protesters. These are the small but important stories that we are able to cover. We have published eight editions so far; most of us are working over the phone — partly because we have no proper internet access here — and we are typing and editing the content for the newsletter as it is reported to us.

The Trolley Times gives a platform to first-time protesters, young protesters, elderly protesters and single women protesters.

We started another initiative called “Trolley Talkies,” which involves showing films about the farmers’ crisis as well as revolutionary movies about the Indian Independence Movement and other movements across the world. We show movies to energize people by entertaining them and educating them about the farm bills: we make connections across time and space by showing how neoliberalism builds upon the foundation established by British colonialism. First-time protesters in particular need to understand the historical nature of these protests: how are they linked to policies that were introduced in India in the 1970s, ’80s and ’90s? How were these policies forced upon the people, and what are their implications? We have undertaken these and other artistic initiatives with the understanding that resistance is creative; you can also see this in the many songs that the protesters have composed and all of the artists from Punjab who have come out to support the protests. We need to employ all kinds of art forms to reach the masses.

Throughout our work, we’re trying to make intersectional connections across different issues and policies. When you oppose the privatization of agriculture, you must also oppose the privatization of education, healthcare and everything else. You can’t be selective: neoliberalism is a policy framework and mindset that’s basically doing the same thing to students, to farmers, to workers, to everyone. It has to be fought tooth and nail as a singular entity.

I’m sure you have many options to pick from, but who are some of the most interesting persons you have met in your time out there?

The most interesting person I have met is this 17-year-old girl who came to the protest on her own. Her parents have a small patch of land, and she saw that, if these farm bills stand, her land will not be safe. She won’t be able to continue her education or make a career for herself, thus sacrificing her independence. And so she took a train to Delhi and stayed here for a long time, participating in the protest and looking after the library.

Her case shows how the protesters understand the gravity of this situation: they know that this is a do-or-die scenario. It also shows how this movement is not just about agencies like Khalsa Aid [an international humanitarian NGO based on Sikh principles] that are setting up big stalls to help people. This is also a movement in which people are coming out and helping at an individual level. You can find a lot of other similarly powerful stories here: whole families have come to the protest and haven’t left for the past two months. Young students are taking their exams here. Young professionals have left their jobs to be here. You see activists coming from all spheres of life: this is a mass movement, not a student movement, which tends to draw upon a very select population of the country. You can find an 18-year-old truck driver protesting alongside a PhD student like me. These kinds of social connections would have been impossible to imagine in normal times. This movement is basically a school of democracy: you learn that this is the people in all its variety, and you need to figure out how to work with them. A kind of professionalization is taking place among all the activists here, whether this involves media work, domestic labor, or any other tasks we undertake.

You have already talked about how the pro-state and pro-corporate media has been covering and, in key respects, not covering these protests. Would you like to address any specific misconceptions intentionally or unintentionally propagated by the Indian and international media, be it mainstream, independent, or even progressive or leftist?

How much should we expect of the Indian media? Two companies own 80 percent of the media. Reliance alone owns 36 news channels. They basically peddle lies day and night. They show a 10-year-old video as evidence that the protesters are Khalistani separatists [demanding a Sikh homeland]. That’s why, when a lot of media come here, their reporters don’t show their name tags and even cover up the tags on their mics; they know that they have no credibility here.

I think the biggest misconceptions about these protests is that these are rich people protesting, that they are motivated by electoral politics, and, of course, that foreign powers are behind these protests and that they are “anti-national” and anti-constitutional. One thing is clear: all protesters are bad protesters to this government. Students are anti-national, women are anti-national, Dalits are anti-national, Muslims are anti-national, workers are anti-national, farmers are anti-national. This is a majoritarian government for whom only a minority of people are actually citizens: the rest are all anti-nationals. This narrative is not only promoted by the government: it has been repeated by the pro-state media, and it has seeped into the international media’s coverage as well.

This movement is basically a school of democracy: you learn that this is the people in all their variety, and you need to figure out how to work with them.

Another misconception is that these protesters do not know about the law. The government and the pro-corporate, pro-state media are saying that the privatization of agriculture is good because it promotes competition. Competition among whom?

One more major misconception is that this protest only involves the Sikh farmers of Punjab. The government and mainstream media are trying to give the protests a religious angle, because that’s very easy, right? When minorities go against the majority and the majoritarian state, they are terrorists, right? We are trying to counter the idea that these are just some Punjabi Sikh men protesting against the Indian state through all our initiatives and activities. Protests are happening in virtually every part of India: Punjab, Haryana, Rajasthan, Gujarat, Maharashtra, Kerala, Tamil Nadu, Bihar, Uttar Pradesh, Orissa, West Bengal, Chhattisgarh, Uttarakhand, Himachal Pradesh, and even Kashmir. Just because all of these protesters are not at the Delhi border does not mean that they are not protesting.

We have also said again and again that we are here to peacefully protest and so, if anything goes wrong, the state is responsible. If anything unruly happens, we make sure we record it, so that we can provide those recordings to any media we contact and say, “Look at what we have witnessed.” We know that, when it comes to violence, no one can beat the state: it is the ultimate agent of violence, sometimes through the law and sometimes more directly through the police.

Why should people of conscience, especially progressives and leftists, across the world care about these protests and the issues that the farmers are addressing? How are these issues and the corresponding protests globally interconnected? And how have people of conscience from outside of India been showing meaningful solidarity with the farmers and how can they continue to do so?

Solidarity protests have been happening across the world; the mass support that these protests have received extends to the South Asian diaspora. The Trolley Times has further been translated into several languages and distributed not only in different parts of India but in Canada, Australia, New Zealand and the United States as well.

At a foundational level, I’d desist from saying that this is a “farmers’ protest.” I’d only say that farmers are leading the protest. India is a poor country with a few rich people. Between 70 and 80 percent of Indians suffer from malnutrition. The Essential Commodities Act allows private businessmen to hoard essential items such as food grains and oil. The de-regularization of prices allows for black markets in such a way that you might end up with godowns [warehouses] full of food grains and a huge population at threat of starvation. In that sense, these laws are an attack not just on farmers but on everyone who eats. This should be a concern for everyone across the world who believes that every human being has a right to eat.

India also accounts for one-sixth of the world’s population. These laws stand to affect the food security, nutrition and overall health and safety of a huge number of people, which in itself should make them everyone’s concern.

Privatization is also a global phenomenon. Raise your voice against privatization in your home country. We don’t just want you to stand with us: we want you to stand up for yourself. These multinational companies have to be defeated not only in India, but also Africa, America, Australia, Europe — everywhere. Everyone is on their radar, and, to counter multinational companies, we need multinational protest.

In addition, these laws rob farmers on the one hand and consumers on the other. I am not here just to support farmers; I am also here as a consumer. I know that I will have to pay so much more to have a basic meal if these laws are implemented. Why should consumers pay so much for food when farmers aren’t even getting a fair price for their agricultural products?

What are the most significant challenges that this struggle will have to overcome if it is to prevail?

Since Day One, the movement has been trying to build broader solidarity. The protesters have been very careful to cause as little inconvenience as possible to local residents. We have also been trying to get them on our side through our media initiatives, with quite a lot of success. Government authorities have not been able to dismiss these protests as a one-off, despite their best efforts.

I think the biggest challenge is the arrogance of this government. State authorities have a tendency to do what they say. They know that these farm laws are dangerous, but, because they have already passed them, they will open up space to address much of their previous wrongdoing if they back down.

But this is to be expected of a government run by proto-fascist strongmen, right? Strongmen can never afford to seem weak, by their very definition.

The myth of the strong leader has to be busted. In a way, I think that this protest has already been successful, because it has democratized a large part of the population, even in just this one small part of India. The protesters have decided that the republic belongs to the people, not to the government.

Every day is very challenging. Any small incident of violence that could be attributed to us, even if we’re not responsible, could threaten the entire movement. Every passing moment is a relief, but the very next moment is a threat. There is a constant threat of state-sponsored violence on both the smaller and larger scale: people have been caught here with small guns. We are basically on night duty right now, looking out for any suspicious persons till 5:00 in the morning. We have been protesting for two months, and we don’t want something spectacular to happen one day that makes everything erupt. In that sense, it’s good that people have not been joining the movement in the thousands; rather, they have consistently been joining in the hundreds.

The protesters have decided that the republic belongs to the people, not to the government.

As I said before, this is not a fight against one government but rather an entire policy framework. Even if we are able to scrap these laws for now — and the government has admitted that it can put them on hold for 18 months — they will undoubtedly be brought back, with a more shrewd design and more brute force behind them. This is a fight that requires us to be on the tips of our toes for the rest of our lifetimes. The good thing is that, when people fight against the government, they gain a muscle memory and a consciousness that is the essence of democracy. A big chunk of the country is remembering what actually brought us independence from the British.

If this movement succeeds, you will see a flurry of mass movements around different issues. If these protests are not able to achieve their concrete goals, however, there will be a large vacuum in the imagination of the people, because they will think that, if protests of this scale cannot force the hand of this government, then nothing can.

Would you like to add anything before we sign off?

I’d just say to people who read this interview that we can’t theorize this movement yet. This is history in the making, but we still don’t know what kind of history it will be. Many of the people who are protesting right now never imagined that they would have to protest for something like this. We have to realize that the neoliberal system is going to consume each and every one of us — not just the most dispossessed, but even those who are slightly well-off. If you have a hundred people sitting in a room, and someone comes in and says, “One of you has to die,” everyone feels the threat that they could be the one. Don’t wait until you get attacked: notice when people around you are getting attacked, and raise your voice.

Protest gives us life: it gives us a fighting spirit and a sense of ownership. This country is ruled by a fascist government right now, but protest brings us back to our roots by saying, “This is our land. This is our people.” I think that kind of organic rather than national chauvinist engagement with your geographical part of the world, as well as your engagement with your own community, is absolutely vital.

Protest gives us life: it gives us a fighting spirit and a sense of ownership.

STANDING WITH INDIA’S FARMERS

Mukesh’s intimate, nuanced insights into India’s ongoing farmers’ rebellion stimulate as many questions as they answer. In spite of our lengthy conversation, we could not possibly cover the protests in all their complexity. Dalit — caste-oppressed — rights advocates both in India and the United States have inquired as to how the protesters intend to address the caste hierarchies that persist in agricultural communities across Punjab and the country as a whole, at the same time as a significant number of landless Dalits have declared their solidarity with the protesting farmers. Contradictions of this kind are almost bound to emerge within protests of the scale at hand, especially in a society that has yet to fully break out of the shackles of feudalism. The inevitability of these contradictions, should, of course not naturalize them and prevent their interrogation, not least of all because of their potential to weaken the movement in question overall.