by DGR News Service | Oct 12, 2021 | Education, Movement Building & Support, Strategy & Analysis

This article is from the blog buildingarevolutionarymovement.

This post looks at what is social change, causes of social change, what is historical change, and theories of social and historical change. This final section of the post includes something on Marxist theories of history.

I looked at theories of change at the social movement and institutional level in previous posts: part 1, part 2, part 3.

What is social change?

Social change is the changes to the social structure and social relationships of society. There is also cultural change. Social changes include changes in age distribution, birth rates, changes in the relationship between workers and employers when there is more union activity. Cultural changes include the invention and popularisation of new technology, new words added to a language, changing concepts of morality, new forms of music and art. They overlap and all important changes include both social and cultural changes. In sociology, ‘sociocultural change’ is used to describe changes of both forms. [1]

The main characteristics of social change include:

- social change is universal to all societies

- social change happen across a whole community or society, not small groups of individuals

- the speed of social change is not uniform within a society

- the speed of social change is different in each age or period, it is faster than in the past

- social change is an essential law of nature

- definite prediction of social change is not possible

- social change shows a chain-reaction sequence – on change leads to the next

- social change results from the interaction of several factors

- social changes generally result in modification or replacement [2]

Causes of social change

There are several causes of social change:

- Natural factors such as storms, earthquakes, floods, drought and disease

- geographical factors such as availability or national resources and levels of urbanisation

- demographic factors such as birth and death rate

- socio-economic factors such as levels of industrialisation, market capitalism and bureaucratisation

- cultural factors as describes in the section above

- science and technology factors

- conflict and competition factors such as war and popular movements for change

- political and legal power factors such as redistribution of wealth or corporate power

- ideas and ideology factors such as religious beliefs, political and economic ideology

- diffusion factors which is the rate that populations adopt new goods and services

- acculturation which is the modification of the culture of a group due to contact with a different culture [3]

What is historical change?

This is gradual and fast (rupture) transformation change in society. The transition from feudalism to capitalism was a historical, transformation change. So is a transition from capitalism to an alternative – socialism, communism.

Theories of social and historical change

There are four broad theories of social change: evolutionary, cyclical, functionalist, and conflict. And several other theories of historical change.

Evolutionary theories

These are based on the assumption that societies gradually change from simple or basic to more complex. There are three forms.

Linear or unilinear evolution describes the change to be progress to something better, more positive and beneficial to reach higher levels of civilisation. This theory was developed by the early theorists of human society in the 19th century. They believed that each society would pass through a “fixed and limited number of stages in a given sequence.”

Universal evolution is similar to the previous theory but does not view each society going through the same fixed stages of development.

Multilinear evolution has been developed by modern anthropologists. They see the process of social change as flexible, open-ended and not a universal law. They still see societies developing from small-scale to large-scale and complex. These theorists state that change takes place in many different ways and does not follow the same direction in every society. They do not believe that ‘change’ means ‘progress.’ [4]

Cyclical theory

This is also known as process theory and natural cycles. This describes how civilisations go through a process of birth, growth, maturity, decline and death in the same ways as living beings. Then the process is repeated with a new civilisation. [5]

Functionalist theories

These theories focus on social order and stability so some argue this limits their ability to explain social change. These theories ask what function different aspects of society play in maintaining social order. Examples include religion, education, economic institutions and the family. Some see society as at equilibrium and change results in a new equilibrium forming. Changes can come from other societies outside the society or from inside. [6]

Conflict theories

These can be seen as a response to the functionalist theories, that were seen to not have a place for change so could not explain social change. Conflict theorists argue that institutions and practices were maintained by powerful groups. Conflict theorists do not believe that societies evolve to a better place but that conflict is necessary for change and groups must struggle to ensure progress. Conflict theories are influenced by Karl Marx. [7]

Great man theory of history

This is a 19th-century idea that states that history is driven by great men or heroes, who are “highly influential and unique individuals who, due to their natural attributes, such as superior intellect, heroic courage, extraordinary leadership abilities or divine inspiration, have a decisive historical effect.”[8] Recently this concept has been ‘de-gendered’, replacing ‘Great Man’ with ‘Big Beasts’ [9]

Marxist theories of history

Karl Marx and Friedrich Engels wrote about and inspired several Marxist theories of historical and social change. See a previous post on Marx’s Marxism.

The materialist conception of history (or Historical materialism), Marx argued that the material conditions of a society’s mode of production (productive force and relations of production) that determine a society’s organisation and development and not ideas or consciousness. ‘Material conditions’ mean the ability for humans to collectively reproduce the necessities of life. [10]

Dialectical materialism can be understood as Marx’s framework for history:

“History develops dialectically, that is to say, by a succession of opposing theses and antitheses followed by their synthesis, which contains part of each original thesis. For Marx, this dialectical process would necessarily be a material one; developments in the substructure of economic life, such as those in production, the division of labor, and technology, all have enormous impact on the superstructure of the political, legal, social, cultural, psychological, and religious dimensions of human society.” [11]

Marx and Engels’ “stages of economic development, or modes of production, build on one another in succession, each brought about by a development in technology and social arrangement” They argued that societies pass through various stages with their own social-economic system – slavery, feudalism, capitalism, communism. Each stage develops because of conflict with the previous one. [12]

Economic determinism states the economic relationships such as being a business owner or worker, are the foundation on which political and societal arrangements in society are based. Societies are therefore divided into conflicting economic classes (class struggle) whose political power is determined by the makeup for the economic system. There is some controversy over Marx and Engel’s exact position on this concept. [13]

There is a Marxist gravediggers thesis (also known as gravediggers argument/dialectic or Marxist teleological theory of history). This is based on the quote from the Communist Manifesto “What the Bourgeoisie therefore produces, above all, are its own grave diggers.” That the internal contradictions of capitalism will result in its inevitable destruction. As capitalism continues the class antagonism between the bourgeoisie and the proletariat will increase and push more and more people into the proletariat. [14] There is some controversy about this theory among Marxists and this post does a good job arguing that the end of capitalism is not inevitable.

Technological theories

Technology refers to the use of knowledge to make tools and utilise natural resources. Changes in technology result in changes in social relations. For Marx, “the stage of technological development determines the mode of production and the relationships and the institutions that constitute the economic system. This set of relationships is in turn the chief determinant of the whole social order.” [15]

Multiple causation theory of history

This states that historical change is complex and likely due to multiple causes related to political, economic, social, cultural and environmental events, as well as the significant individuals. [16] Max Weber supported this perspective “historical events are a matter of the coming together of independent causal chains which have previously developed without connection or direct import for one another” [17]

World-systems theory

This is a large scale approach to world history and social change, with the focus of social analysis on the world-system over the nation-state. The ‘world-system’ refers to the inter-regional and international division of labour, which divides the world into ‘core countries’, ‘semi-periphery countries’ and ‘periphery countries’. Core countries focus on ‘higher skilled capital-intensive production’, with the rest of the world focusing on ‘low-skilled, labour-intensive production’ and extraction of raw materials. Immanuel Wallerstein’s World-systems theory describes the shift from feudalism to capitalism; and then during the modern era, the centre of the core has moved from the Netherlands in the 17th century, Britain in the 19th century and the US after World War I. [18]

Endnotes

- https://www.masscommunicationtalk.com/different-theories-of-social-change.html

- https://www.sociologydiscussion.com/sociology/theories-of-social-change-meaning-nature-and-processes/2364

- http://people.uncw.edu/pricej/teaching/socialchange/causes%20of%20social%20change.htm, https://ourfuture.org/20080514/why-change-happens-ten-theories, https://www.shareyouressays.com/knowledge/7-main-factors-which-affect-the-social-change-in-every-society/112456)

- https://www.masscommunicationtalk.com/different-theories-of-social-change.html, https://www.sociologydiscussion.com/sociology/theories-of-social-change-meaning-nature-and-processes/2364, https://www.yourarticlelibrary.com/sociology/top-5-theories-of-social-change-explained/35124, https://guide2socialwork.com/theories-of-social-change/, https://www.academia.edu/25227760/Theories_of_Social_Change, https://www.shareyouressays.com/knowledge/6-most-important-theories-of-social-change-2/112462, https://article1000.com/theories-social-change/

- https://www.masscommunicationtalk.com/different-theories-of-social-change.html, https://www.sociologydiscussion.com/sociology/theories-of-social-change-meaning-nature-and-processes/2364, https://science.jrank.org/pages/8918/Cycles-Twentieth-Century.html, https://www.yourarticlelibrary.com/sociology/top-5-theories-of-social-change-explained/35124, https://guide2socialwork.com/theories-of-social-change/, https://www.shareyouressays.com/knowledge/6-most-important-theories-of-social-change-2/112462, https://article1000.com/theories-social-change/

- https://www.masscommunicationtalk.com/different-theories-of-social-change.html, https://www.yourarticlelibrary.com/sociology/top-5-theories-of-social-change-explained/35124, https://guide2socialwork.com/theories-of-social-change/, https://www.shareyouressays.com/knowledge/6-most-important-theories-of-social-change-2/112462, https://article1000.com/theories-social-change/

- https://www.masscommunicationtalk.com/different-theories-of-social-change.html, https://www.yourarticlelibrary.com/sociology/top-5-theories-of-social-change-explained/35124, https://guide2socialwork.com/theories-of-social-change/, https://article1000.com/theories-social-change/

- https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Great_man_theory

- https://www.historytoday.com/archive/head-head/there-still-value-%E2%80%98great-man%E2%80%99-history, https://www.andrewbernstein.net/2020/01/the-great-man-theory-of-history/, https://www.visiontemenos.com/blog/the-great-man-theory-of-1840-leadership-history, https://www.communicationtheory.org/great-man-theory/

- https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Historical_materialism

- Dialectical Materialism and Economic Determinism: Freedom of the Will and the Interpretation of Behavior, Estelio Iglesias http://www.fau.edu/athenenoctua/pdfs/Estelio%20Iglesias.pdf

- Dialectical Materialism and Economic Determinism: Freedom of the Will and the Interpretation of Behavior

- https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Economic_determinism

- https://www.enotes.com/homework-help/explain-quote-what-bourgeoisie-therefore-produces-99615

- https://www.yourarticlelibrary.com/sociology/top-5-theories-of-social-change-explained/35124, https://www.yourarticlelibrary.com/sociology/top-5-theories-of-social-change-explained/35124, https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/William_Fielding_Ogburn

- https://aeon.co/ideas/we-must-recognise-that-single-events-have-multiple-causes

- Perspectives in Sociology, E.C. Cuff, 2006, page 46

- https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/World-systems_theory#The_interpretation_of_world_history

by DGR News Service | Oct 10, 2021 | Colonialism & Conquest, Indigenous Autonomy, Listening to the Land, Movement Building & Support, Repression at Home

This article originally appeared in Survival International.

Featured image: The Ayoreo have previously blocked the trans-Chaco Highway to draw attention to government inaction over the destruction of their forest. © GAT/ Survival

The survival of the last uncontacted tribe in South America outside the Amazon is at stake.

Indigenous people living in a South American forest with one of the world’s highest rates of deforestation have appealed to the Inter-American Commission on Human Rights to save it from total destruction. Their uncontacted relatives are fleeing from one corner of the remaining forest to another, seeking refuge from ever-present bulldozers.

The Ayoreo-Totobiegosode of Paraguay’s Chaco forest have been trying since 1993 – when they submitted a formal land claim – to protect their forest in the face of a rapidly expanding agricultural frontier.

In 2013, given a total lack of political will in Paraguay to uphold the law and stop the destruction of their lands, they requested that the Inter-American Commission on Human Rights intervene.

In 2016, at the government’s request, they agreed to enter formal negotiations with the government for their land titles, but for 5 years, and despite 42 meetings, the destruction of their forest has continued unabated. Satellite photos reveal that the Ayoreo now live in an island of forest surrounded by monocultures and beef production.

The Ayoreo have now announced they are pulling out of the negotiations, and have written again to the Inter-American Commission, asking it to order the Paraguayan authorities to finally return their land to them, and expel the agribusiness corporations that have taken it over.

Although most Ayoreo-Totobiegosode were forcibly contacted by American evangelical missionaries some years ago, an unknown number remain uncontacted in the last island of their forest, which is now being cut down around them.

Earlier this year one uncontacted group made contact with a settled community of their relatives, to express their fear at the destruction of their forest refuge, before returning to the forest.

The Ayoreo-Totobiegosode leader Porai Picanerai, who was forcibly contacted by the American New Tribes Mission in 1986, said: “My uncontacted relatives are suffering and in danger because they barely have any space now to live in. There are many outsiders occupying our land and burning the forest for beef production.”

Porai also said: “After having participated in most of the 42 meetings, I can confirm that the government doesn’t keep its word, that it lies and doesn’t want to protect my people or return the lands that we’ve always lived in and cared for. We’ll only get the government to act by going to outside bodies like the Commission.”

Survival Researcher Teresa Mayo said today: “The Ayoreo-Totobiegosode have called a halt to the negotiation process as the government was just dragging it out while allowing the rampant destruction of the Ayoreo’s forest to continue. The state knows that it simply has to do nothing to effectively condemn the uncontacted Ayoreo to death – and if a government sees the solution to its “problem” as the extermination of a people, we’re talking about genocide.”

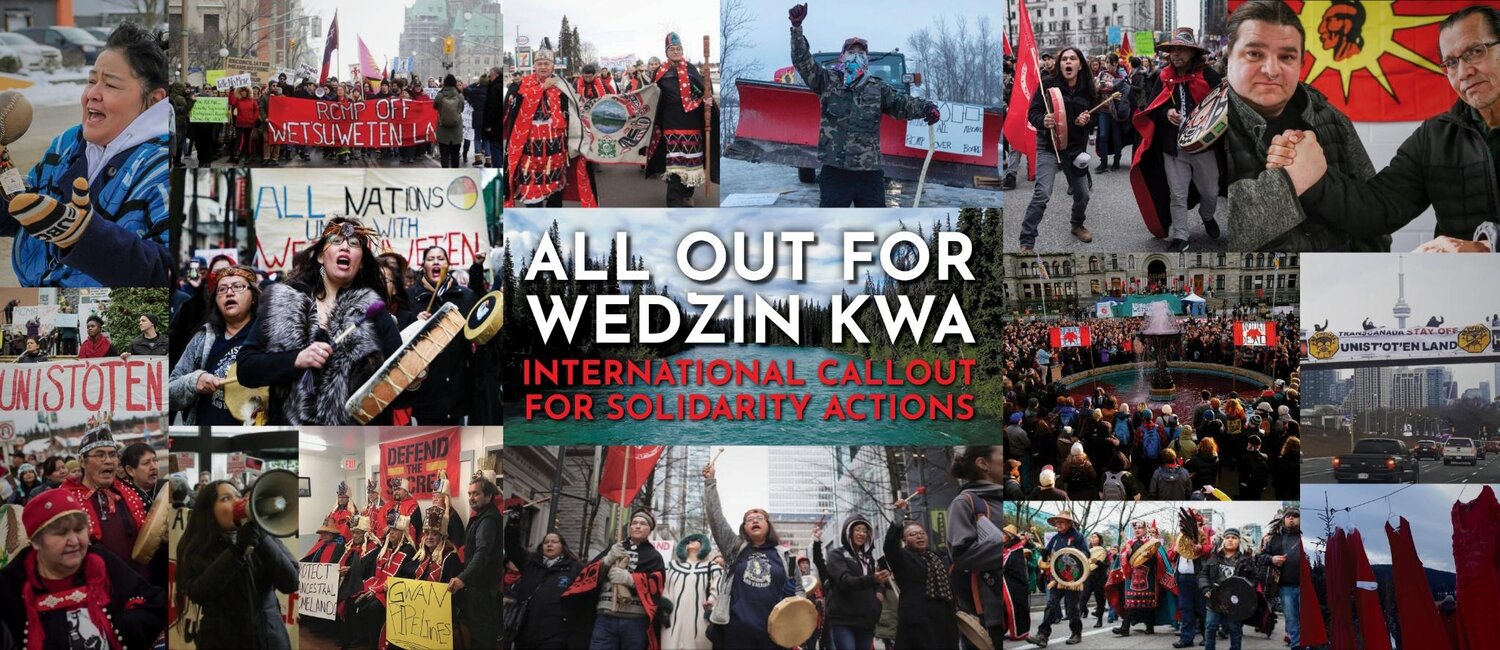

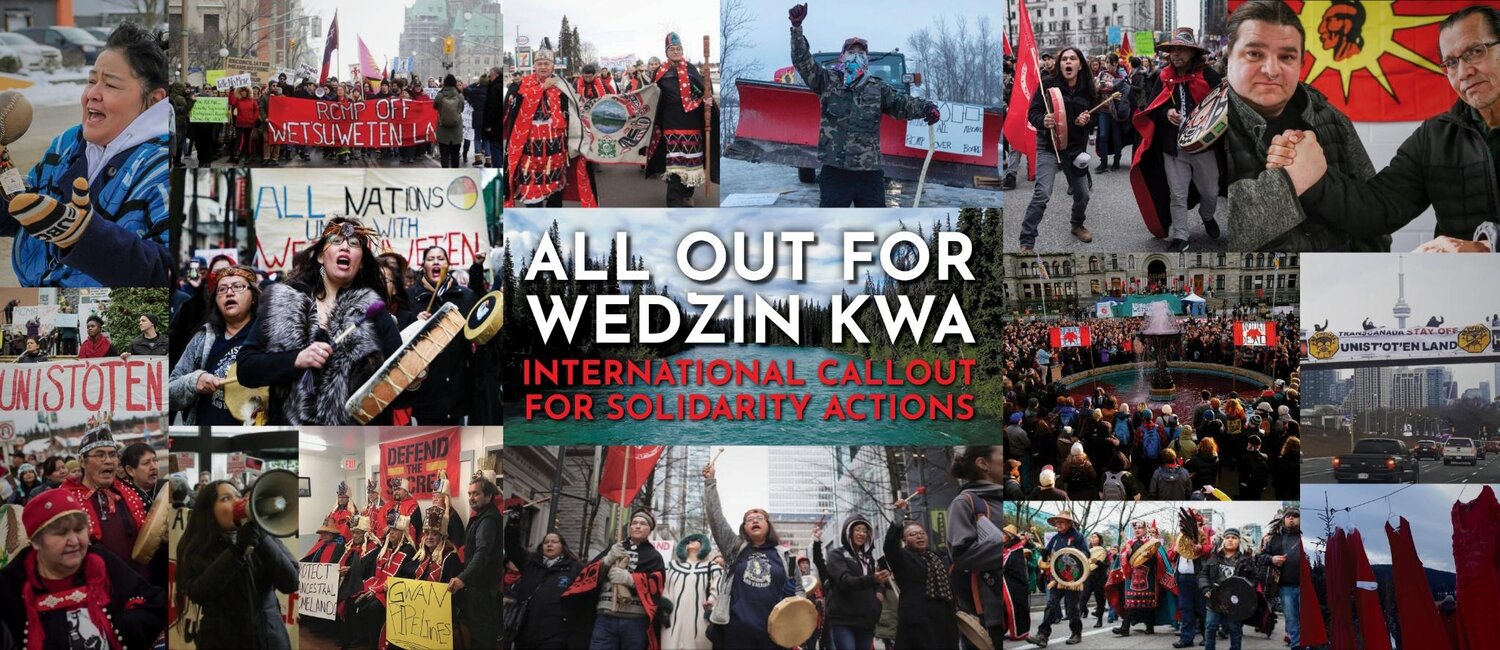

by DGR News Service | Oct 9, 2021 | Biodiversity & Habitat Destruction, Colonialism & Conquest, Direct Action, Indigenous Autonomy, Lobbying, Movement Building & Support, Protests & Symbolic Acts, Repression at Home, Toxification

Original Press Release

Cas Yikh of the Gidimt’en Clan are counting on supporters to go ALL OUT in a mobilization for the biggest battle yet to protect our sacred headwaters, Wedzin Kwa. We have remained steadfast in our fight for self-determination, and we are still unceded, undefeated, sovereign and victorious.

In January 2019, when Gidimt’en Checkpoint was raided by the RCMP, enforcing an injunction for Coastal GasLink fracked gas pipeline, your communities rose up in solidarity!

You organized rallies and marches. You published Solidarity Statements. You wrote your representatives. You put on fundraisers and donated to the Legal Fund. You pledged to stand by the Wet’suwet’en. The pressure worked to keep Wet’suwet’en land defenders and supporters safe as they navigated the colonial court system. All charges were dropped.

In January 2020, you answered the call to #SHUTDOWNCANADA! The world watched as the RCMP violently confronted unarmed Wet’suwet’en land defenders, on behalf of CGL, in an intense 6-day struggle for control over the territory, following industry’s eviction by Hereditary Chiefs.

This invasion ignited a storm of solidarity! The Wet’suwet’en were embraced in beautiful and powerful actions coast to coast and overseas. During February and March, thousands of people rose up in hundreds of demonstrations in solidarity with Indigenous sovereignty and environmental protection against the fracked gas industry.

During a wave of international uprisings, Canada came under fire for its refusal to engage in meaningful Free, Prior and Informed Consent with Indigenous Nations across Turtle Island. Canada’s denial of responsibility and failure to implement the United Nations Declaration of the Rights of Indigenous Peoples resulted in the fight for #LANDBACK.

We are humbled by the power of our allies, friends and supporters. We have love, respect, and gratitude for those that stood their ground beside us on the yintah to defend Wedzin Kwa. We vow to reciprocate the solidarity from everyone that followed, all our allies/relatives and supporters that put their feet in the street defending Indigenous sovereignty.

Now, we need you to rise up again.

October 9th-15th 2021, go #AllOutForWedzinKwa

⭐ Come to the land: https://www.yintahaccess.com/come-to-camp

⭐ Find or host a solidarity rally near you: https://fb.me/e/1fv4oHsfv

⭐ Pressure the government : call the BC Oil and Gas Commission, the Ministry of Forests and the Environmental Assessment office:

BC Oil and Gas Commission (2950 Jutland Rd, Floor 6, Victoria BC): https://www.bcogc.ca/what-we-regulate/major-projects/coastal-gaslink/

Minister of Forests, Lands, Natural Resource Operations & Rural Development Contacts:

https://www2.gov.bc.ca/gov/content/governments/organizational-structure/ministries-organizations/ministries/forests-lands-natural-resource-operations-and-rural-development/ministry-contacts

Enviromental Assement Office: https://projects.eao.gov.bc.ca/p/588511c4aaecd9001b825604/project-details

-

PROJECT LEAD: MEAGHAN HOYLE; (778 974-3361), MEAGHAN.HOYLE@GOV.BC.CA

-

EXECUTIVE PROJECT DIRECTOR: FERN STOCKMAN; (778 698-9313), FERN.STOCKMAN@GOV.BC.CA

-

COMPLIANCE & ENFORCEMENT LEAD: COMPLIANCE & ENFORCEMENT BRANCH (250-387-0131), EAO.COMPLIANCE@GOV.BC.CA

⭐ Donate: https://go.rallyup.com/wetsuwetenstrong/Campaign/Details

⭐ PayPal yintahaccess@gmail.com

⭐ Share our posts: Use the hashtag #AllOutForWedzinKwa to spread the word!

⭐ Check out our TAKE ACTION page for resources and previous actions

The time is NOW to recognize Indigenous sovereignty around the world.

It is up to the Gidimt’en, Wet’suwet’en, and our supporters to determine the fate of future generations. #ALLOUTFORWEDZINKWA

More info:

1 year recap with Dr Karla Tait : https://directory.libsyn.com/episode/index/id/17858045/tdest_id/1618577

Solidarity action archive: https://www.yintahaccess.com/new-folder

1 year recap video: https://www.facebook.com/watch/?v=540243243557568

by DGR News Service | Oct 6, 2021 | Culture of Resistance, Human Supremacy, Indigenous Autonomy, Indirect Action, Mining & Drilling, NEWS, Protests & Symbolic Acts, The Problem: Civilization, The Solution: Resistance

Editor’s note: The industrial civilization always prioritizes access to “resources” over rights of indigenous people. DGR believes that those in power break laws when it suits their interest. We stand in solidarity with indigenous struggles to protect their landbase.

This article originally appeared in Survival International.

Hundreds of tribal villagers from India’s Hasdeo Forest begin a rally and march tomorrow in protest at the government’s plans for a massive expansion of coal mining on their lands.

People from Adivasi (Indigenous) communities who live in the forest – which, at 170,000 hectares, is one of the largest intact areas of forest in the country – will rally on Gandhi’s birthday (October 2), then march 300km to the capital of Chhattisgarh state from October 4-13.

The Hasdeo Forest is the ancestral home of approximately 10,000 Adivasis belonging to the Gond, Oraon, Lohar, Kunwar and other peoples. It is also one of India’s richest and most biodiverse regions.

Indian Prime Minister Modi’s government is aggressively promoting a plan to open new coal mines in the area. The forest and its peoples would be destroyed if the mines go ahead.

Across India Modi intends to open 55 new coal mines and expand 193 existing ones, to increase coal production to 1 billion tonnes a year. Coalfields are being auctioned off to some of India’s biggest mining corporations, including Adani, Vedanta and Aditya Birla.

Much of the existing government plan is illegal, as mining in Adivasi land should not proceed without their consent. Across India Adivasis are deeply opposed to the mines, having seen first-hand how existing mines have destroyed forests and the communities that lived in them.

Adivasi people across India have been resisting mining for decades, including by blocking bulldozers and peacefully protesting. Many have been arrested, beaten and even murdered in response.

In a public declaration from the “Resistance Committee to Save Hasdeo Forest” (Hasdeo Aranya Bachao Sangharsh Samiti) the Adivasis said:

The federal and the state government, instead of protecting the rights of us tribal and other traditional forest dwellers have joined hands with mining companies and have been working towards devastating our forest and land.”

“We are bound to resist and [march] to safeguard our water, forest, land and our livelihoods and culture that are dependent on them. We appeal to all citizens who love the Constitution and Democracy, all who are committed to safeguard the waters, forests, land and environment and all sentient citizens to join us in this gathering and the march.”

Survival International Director Caroline Pearce said today: “The extent of the coal mining now planned will not only destroy Indigenous homes, lands and livelihoods on an unimaginable scale, it also makes a mockery of Modi’s claim to be at the forefront of addressing the climate crisis. Supporting the Adivasi resistance to coal mining should be a global priority.”

Photo by Amir Arabshahi on Unsplash

by DGR News Service | Oct 3, 2021 | Movement Building & Support, Protests & Symbolic Acts, Repression at Home, Strategy & Analysis

Editor’s note: “The strategies and tactics we choose must be part of a grander strategy. This is not the same as movement-building; taking down civilization does not require a majority or a single coherent movement. A grand strategy is necessarily diverse and decentralized, and will include many kinds of actionists. If those in power seek Full-Spectrum Dominance, then we need Full-Spectrum Resistance.”

McBay/Keith/Jensen (2011): Deep Green Resistance, p. 240

This article originally appeared in Waging Nonviolence.

Featured image: Serbians hit a barrel with Milosevic’s face on it. (Actipedia)

A study of 44 dilemma actions over the last 90 years examines the many benefits of creative protests for social movements.

By James L. VanHise

At 7:30 p.m. on Feb. 5, 1982, the streets of Swidnik, a small town in southeast Poland, suddenly became crowded. People strolled and chatted. Some carted their TV sets around in wheelbarrows or baby strollers.

The residents of Swidnik had not gone insane.

They were protesting the lies and propaganda they were hearing on the government’s TV news, which aired at that time every night. Two months earlier, in an attempt to suppress unrest and crush the Solidarity trade union, Gen. Wojciech Jaruzelski had declared martial law in Poland.

As the protests began to spread to other towns, the communist government faced two unattractive choices: arrest people for simply walking around, or let the symbolic resistance continue to propagate. Because the Polish authorities were put in a situation where they had no good options, the Swidnik walkabout could be considered a dilemma action.

This is one example cited in a recent publication called “Pranksters vs Autocrats: Why Dilemma Actions Advance Nonviolent Activism,” written by Srdja Popovic and Sophia McClennen.

“Dilemma actions are strategically framed to put your opponent between a rock and a hard place,” Popovic told me in an interview. “If your opponent reacts, there will be a cost. If your opponent doesn’t react, there will be a cost.”

Popovic is executive director of the Center for Applied Nonviolent Action and Strategies, or CANVAS, an organization that trains activists around the world in civil resistance strategies and tactics. From real-world experience, he knew that using creative tactics like dilemma demonstrations and humor — what the authors call “laughtivism” — could be powerful tools for resisting authoritarian regimes or struggling for human rights.

It was his friend McClennen, a professor at Penn State University, who suggested they do a pilot study to quantify the value of such methods and include the results in the book. The research examined 44 dilemma actions between 1930 and 2019.

The case studies included the well-known barrel stunt concocted by Otpor, the Serbian youth group that was instrumental in ousting dictator Slobodan Milosevic in 2000. Otpor pranksters found an old barrel and painted Milosevic’s face on it. After alerting the press, they placed the barrel, along with a heavy stick, in a busy upscale shopping district. A sign instructed passersby to “smash his face for a dinar. ” Soon people were lining up to deposit a coin and take a whack at their leader’s image.

Eventually the police arrived and, with the Otpor perpetrators laughing safely from a nearby coffee shop, the police vacillated. Do they arrest the mostly middle-class families who were standing in line, and risk provoking more opposition to the government? Or do they let the protest continue and potentially spread to other parts of the country? The police chose a third option. They arrested the barrel, and the next day the nation laughed when the opposition press ran pictures of the cops wrangling the barrel into their squad car.

Another case included in the study occurred in Russia. When the residents of a Siberian city were denied a permit to hold a street protest in 2012, they found a humorous workaround — have their toys demonstrate instead.

Activists staged a group of teddy bears, Lego people, toy soldiers and the like, all holding signs denouncing electoral corruption. Photos of the rebellious figurines spread across Russia, and soon others were reproducing the action.

Putin’s government was faced with two distasteful options: allow the dissent to flourish by ignoring the protests, or crack down on the tiny toy tableaus and look silly. The government chose to outlaw the action. Toys are not Russian citizens and therefore can’t take part in meetings, explained a government official in issuing the toy protest ban.

Like most tactics, dilemma actions rarely lead to the immediate granting of demands by the adversary. But generating a dilemma can sometimes dramatize injustices or contradictions in an opponent’s policies, making the invisible visible and changing the narrative around an issue. In fact, initial results of McClennen’s study suggest dilemma actions have the potential to provide a number of benefits that can help activists build successful civil resistance campaigns.

For example, protests that create dilemmas for an opponent are extremely successful at garnering media attention, attracting more supporters, and reducing fear among activists. The study also showed that incorporating a humorous element is an effective way of reframing the image of an authoritarian leader — from powerful or scary to weak and vulnerable.

McClennen, who stresses the research is very preliminary, is working with CANVAS to do a more rigorous study. “I do think … we will be able to show that a group can have outsized impact … if they use dilemma actions,” she said. “We think it, but we want to prove it.”

“It’s very important to calculate the costs and risks affiliated with a tactic, and involve your opponent’s reaction in the original planning process.”

There have been a few other academic efforts to analyze dilemma actions. “Pranksters vs Autocrats” incorporates ideas from a 2014 paper by Majken Jul Sørensen and Brian Martin that attempted to define some core characteristics of dilemma actions, and identify factors that can complicate an opponent’s response options. Sørensen is associate professor of sociology at Karlstad University in Sweden, and Martin is emeritus professor at the University of Wollongong in Australia.

Martin says that many activists focus solely on what they are going to do — how can they express their anguish about a particular issue. But when they think in terms of planning a dilemma action, they are forced to consider how the other side is likely to respond.

“And as soon as you do that, then you’re thinking strategically instead of just reactively or emotionally,” Martin said. “And I think that’s one of the great values of dilemma actions. They make you realize it’s an interaction, and you need to think about what the opponent might do, and what their choices are, and select your own options in that light.”

The more you think the process through, the more likely you will succeed, says Popovic. “It’s very important to calculate the costs and risks affiliated with a tactic, and involve your opponent’s reaction in the original planning process,” he added.

All acts of resistance operate within preexisting situations. The objective of any such action should be to change the situation so that it is more favorable to the resisters, or less favorable to their adversary. And, in fact, there is no bright line between dilemma actions and other types of nonviolent protest.

“At the simplest level, a dilemma action is an action that poses a dilemma for whoever’s responding to it,” Martin said. “But distinguishing it from a non-dilemma action is not so easy.”

Conventional nonviolent protests and dilemma actions share similar dynamics, because simply refusing to use violence can sometimes create a quandary for the opponent. Imagine human rights activists in an authoritarian country organizing a traditional nonviolent protest march. The dictator may be forced into something of a dilemma.

Ignoring the demonstrators or acceding to their demands may make the ruler appear weak, increasing the prestige and power of the human rights group. On the other hand, beating or arresting nonviolent protesters can seem heavy handed, bringing sympathy and additional support to the group.

So in principle, says Sørensen, who co-wrote the paper on dilemma actions with Martin, any nonviolent action might be considered a dilemma action. “It’s a continuum of different types of actions — some of them obviously involve a dilemma while for others the dilemma is not very clear,” she explained. “The circumstances will play a big role, and whether it is a dilemma will depend on what context are we talking about.”

“Some targets tend to be more vulnerable or more susceptible to dilemma actions. People with big egos, for example.”

Deliberately creating dilemmas for an opponent is not always possible or appropriate. But thinking about how an adversary might react can help inspire creativity when planning any resistance action. Taking into consideration the characteristics of your opponent — their vulnerabilities, motivations, goals, tendencies and so on — is always useful, but essential when designing a dilemma action. That’s because there needs to be a target that will experience the dilemma, and some anticipation of what choices that entity will make.

Getting the target to overreact can be an effective strategy in certain situations. “Some targets tend to be more vulnerable or more susceptible to dilemma actions,” Popovic said. “People with big egos, for example, are very often good targets.”

But cornering an opponent can also risk a violent crackdown. “It’s a very thin line,” Popovic added. “You really don’t want a lot of people to get hurt because of any tactics … because that causes fear.”

While many dilemma actions target a group, like the police or a government, Popovic thinks that singling out an individual is better because it puts the onus of decision on that person. “When you target an institution, you want to figure out who are the people in this institution,” he explained. “When you are personalizing your tactics, it always works better than if you are generalizing.”

A well-known example of a personalized dilemma action unfolded during the height of the Iraq War. Cindy Sheehan, the mother of a soldier who had been killed in action, set up camp outside George W. Bush’s ranch in Crawford, Texas while he was vacationing there. She vowed not to leave until the president met with her and explained the purpose of the war, and why so many young Americans continued to die.

A photo of Casey Sheehan is held by his friends and family of at an anti-war demonstration in Arlington, Virginia on October 2, 2004. Cindy Sheehan herself is partly visible behind a cameraperson at left. Ben Schumin, CC BY-SA 3.0 <http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-sa/3.0/>, via Wikimedia Commons

Over the next three weeks, hundreds of supporters — politicians, celebrities and other bereaved parents — visited the encampment. Almost daily international press coverage of the standoff increased the pressure on Bush, leaving him no good options.

While sitting down with a grieving mother posed risks for the president by spotlighting the human costs of the conflict, every day he refused to meet brought more publicity for the growing antiwar movement. In the end Bush chose not to have the meeting, but the action was instrumental in shaping public opinion against the war.

Dilemma demonstrations have long been used, albeit sometimes accidentally or unconsciously, to leverage gains in resistance campaigns, but only recently have they become the subject of serious study. Works like “Pranksters vs Autocrats” offer insights into the dynamics of dilemma actions, as well as provide some hard evidence on the advantages of this technique.

The main value in thinking about dilemmas may be that it requires activists to plan actions that take into account how the other side is likely to react, and design tactics in ways that make the opponent’s response less effective. This approach can lead to protests that are proactive, strategic and ultimately more compelling.

James L. VanHise is a writer who lives in Raleigh, NC. He has written about Gene Sharp and civil resistance in The Progressive, Peace Magazine, Waging Nonviolence and elsewhere. James blogs about nonviolent strategy and tactics at nonviolence3.com. Follow him on Twitter at @Nonviolence30.

by DGR News Service | Oct 2, 2021 | Climate Change, Human Supremacy, Women & Radical Feminism

This article originally appeared in Common Dreams.

“This is the time to unite together to build the healthy and just future we know is possible for each other and the Earth.”

By JULIA CONLEY

As world leaders gathered in New York for the United Nations General Assembly Thursday and amid preparations for a global climate conference coming up in November, women leading more than 120 international organizations delivered a call to action demanding “a transformation of how we relate to the natural world and to one another”—one that will enable far-reaching action to save the planet.

“As the world prepares for one of the most important climate talks since the Paris Agreement, we know solutions exist to mitigate the worst impacts, and that women are leading the way.” —Osprey Orielle Lake, WECAN International

Led by Women’s Earth & Climate Action Network (WECAN) International, the organizations called on governments and financial institutions to commit to policies that prioritize “social, racial, and economic justice for all” as they work to keep the heating of the planet below 1.5C.

“We must rapidly halt the extraction of oil, gas, and coal and end all deforestation while building a new economy predicated on community-led solutions,” reads the call to action, which was signed by groups including MADRE, CodePink, and Women’s Earth Alliance.

“As we herald in sustainable, democratic, and equitable governance paradigms, we need to prioritize the leadership and well-being of women, gender non-conforming people, Black and Brown communities, and Indigenous peoples who are disproportionately impacted by climate change, but also lead the frontlines of systemic solutions,” the groups said.

The organizations also plan to present their demands at the 2021 U.N. Climate Change Conference (COP 26) in November, where leaders from nearly 200 countries will be under pressure to increase their ambitions to reduce emissions and uphold their existing obligations to frontline communities across the globe, particularly in the Global South.

“We are at a choice point for humanity,” said Osprey Orielle Lake, executive director of WECAN International. “Every day, we can see for ourselves forest fires burning all over the world, massive flooding, extreme droughts, people losing their livelihoods and lives—we are in a climate emergency. As the world prepares for one of the most important climate talks since the Paris Agreement, we know solutions exist to mitigate the worst impacts, and that women are leading the way.”

The call to action includes a number of steps recommended for governments as well as financial institutions, including:

- End fossil fuel expansion and rapidly accelerate a just transition to 100% renewable and regenerative energy;

- Promote women’s leadership and gender equity;

- Protect the rights of Indigenous people by upholding all treaties, and follow Indigenous communities’ traditional ecological knowledge;

- Protect forests and biodiversity with a global moratorium on logging and a phase-out of agricultural practices that cause soil erosion and depletion;

- Preserve oceans and freshwater;

- Promote food security and food sovereignty;

- Protect the rights of nature; and

- Halt the financing of all fossil fuel projects.

The call to action comes ahead of a six-day virtual forum organized by WECAN.

At the Global Women’s Assembly for Climate Justice, which begins Saturday, speakers will include scientist and conservationist Dr. Jane Goodall; Casey Camp-Horinek of the Ponca Nation, a WECAN board member and environmental ambassador; Ruth Nyambura of the African Ecofeminist Collective in Kenya; and Sônia Bone Guajajara of the Articulation of Indigenous Peoples of Brazil.

“As a Matriarch of the Ponca Nation, I am honored to have the responsibility of caring for the generations to come by ensuring the health and welfare of Mother Earth, Father Sky, and Relatives in every form,” said Camp-Horinek. “Life itself hangs in the balance, and we women are coming together to say that we must make the correct choices for our collective future now.”

Events at the six-day forum will include discussions about protecting the planet’s forests, rejecting “greenwashing” by corporations, and supporting feminist frameworks for climate justice.

“We can act now and we must act now, which is why WECAN is hosting the Global Women’s Assembly for Climate Justice to uplift women, gender-diverse and community-led solutions, strategies, policies, and frameworks to address the climate crisis,” said Lake. “It is code red and we are drawing a red line to say no more sacrifice people and no more sacrifice zones. This is the time to unite together to build the healthy and just future we know is possible for each other and the Earth.”