by DGR News Service | Nov 26, 2024 | ANALYSIS, Colonialism & Conquest

Editor’s note: “Renewable” energy power plants continue the exploitation of the natural world and call their ecosystems “resources.”

Robbing Africa’s Riches to Save the Climate (and Power AI)

By Tommaso Marconi / FREEDOM

While renewable energy is seen as part of the solution to many environmental issues we are facing, it is also used as a pretext by capitalist lobbies and colonialism to overcome territorial sovereignty and implement privatisation. The case of Western Sahara is clear: two-thirds of the territory has been occupied by the Moroccan army since 1975, and now Morocco’s main tool to continue the occupation has become the green transition.

The invasion of the former Spanish colonial territories started in November 1975. The Moroccan army used napalm and a devastating amount of violence to gain those territories and forced thousands of Saharawi to flee and become refugees in Algeria and then Europe.

In February 1976 the Saharawi liberation movement Frente Polisario declared an independent Saharawi Arab Democratic Republic. (SADR); in the same month the King of Morocco signed a treaty with Spain and Mauritania where they divided the territory. When Mauritania retreated its army, Morocco entered the zone and occupied it to control the coast until Guerguerat, just north of the Mauritanian border.

In the 1980s, the Moroccan army started building a huge sand wall (the Berm) to stabilise the frontline with the area in which Frente Polisario was active. Today, that wall is the longest in the world, measuring over 2,700 km and surrounded by mined zones. To meet the enormous cost of maintaining and defending the wall, the Kingdom of Morocco exploits and exports Saharawi resources — fish and phosphates.

Corruption

Various rulings by the European Court of Justice (ECJ) have resulted in difficulties for European corporations to enter the trade in Saharawi resources. A treaty on free trade of fish and sand with European corporations was ruled illegal by the European Court in 2015; for the UK that meant the total exit of British enterprises from Western Sahara until 2021. In response, Morocco has resorted to more aggressive diplomacy in Europe and other international spaces.

In November 2022 a huge scandal was disclosed in the European parliament: the Qatargate (also known as Moroccogate). It was proven that Moroccan agents had been corrupting Members of European Parliament (MEP) using an Italian politician, Antonio Panzeri, as a middleman. Some results that Morocco gained from this strategy were: the denial of the Sakharov human rights prize to two Saharawi activists; the passing of resolutions against Algeria, which has been favouring Polisario and hosting Saharawi refugees; the modification of a European report about violence and human rights to erase the Moroccan cases; and an attempt to reverse the rulings against a fishing treaty, which banned EU companies from fishing off the Laayoune shores.

The Abraham Accords signed in 2020 between the USA, Israel, Bahrain, the UAE and Morocco, included complicit recognition of the occupations of Palestine by Israel and Western Sahara by Morocco. Israel has since increased its trade with Morocco, including new drones Morocco has used in the war against Frente Polisario.

The Moroccan army and its colonial administration of Western Sahara’s occupied territories are actively hiding information and data about the exploitation of natural resources. The Western Sahara Resources Watch monitors the exploitation and produces detailed reports on it, but we do not actually know the size of resources that are being extracted and seized by Morocco and sold off in the global market.

The biggest phosphate mine in Western Sahara is the Phosboucraa, but Moroccan institutions do not publish the amount of phosphate extracted there. Instead, they greatly publicise the renewable energy used for extracting and processing the phosphates. The Kingdom’s priority in its green transition is to provide stable energy to its biggest asset, the phosphate mining industry. Thus, the mine receives 90% of the electricity consumption from solar and wind power plants.

Renewable energy

Since 2017, the Moroccan Kingdom has rapidly been investing in the green energy sector, after realising that it lacks fossil fuel reserves, and it needs more energy. At international meetings of states who are parties to the UN Framework Convention on Climate Change, it craftily depicted itself as the most proactive country in renewables in Africa: Marrakech hosted two such meetings, lately in 2017. Since then, renewable energy projects have multiplied, and many more renewable energy power plants have been built. Morocco exploits land, air and sea in Western Sahara despite having no sovereignty over it.

Western Sahara is connected to the Moroccan grid via the capital Laayoune. A new 400kV power connection is planned between Laayoune and Dakhla, and to Mauritania. Through this power-line, Morocco plans to export renewable energy to West Africa. Exports to the EU will occur via existing and planned submarine connections with Spain, Portugal and with the UK. The UK project would see a 3.6GW submarine high-voltage direct current interconnector between the UK and the Occupied Territories, which would generate energy to meet 6% of the UK’s demand. All these plans are particularly focused on cutting the energy trade of Morocco’s first competitor and geopolitical enemy in the Mediterranean region, Algeria.

Morocco’s strategy underlines the place of energy in realising the Kingdom’s diplomatic efforts in securing support for its occupation in traditionally pro-Saharawi independence, pro-Polisario, sub-Saharan Africa (especially Nigeria). The final purpose of this strategy is to strengthen economic relations with African countries in return for recognition of its illegal occupation.

The implications for the Saharawi right to self-determination are huge. These planned energy exports would make the European and West African energy markets partially dependent on energy generated in occupied Western Sahara. The Saharawi people are 500,000: around 30-40,000 live under the Moroccan military occupation and the rest live in the Tindouf refugee camp (the capital of the exiled SADR) in Algeria and some dozen thousands are refugees in Europe.

One form of oppression by the Moroccan army against the Saharawi remaining in the Occupied Territories is by threatening to cut off the electricity in the neighbourhood of Laayoune where most Saharawi live, to make it impossible for them to record violence against the community.

Morocco is quite successful in attracting international cooperation projects in the field of renewable energy. The EU sees the country as a supposedly reliable partner in North Africa, not least because of its alleged role in the fight against international terrorism and in insulating the EU from migratory movements.

There are hundreds of foreign businesses involved in the exploitation of occupied Western Sahara’s natural resources. One of the most active is Siemens Gamesa, because it is involved in all wind power fields in occupied Western Sahara. Siemens Gamesa Renewable Energy (Siemens Gamesa) is the result of a merger, in 2017, of the Spanish Gamesa Corporación Tecnológica and Grupo Auxiliar Metalúrgico, inc. in 1976, and the German Siemens Wind Power, their “green” division. The renewable energy company develops, produces, installs and maintains onshore and offshore wind turbines in more than 90 countries; but the most critical is its participation in 5 wind farms in the Occupied Territories, one of which provides 99% of the energy required to operate the phosphate extraction and export mine of Phosboucraa.

The European Union continues to promote the sector and create alliances with Siemens Gamesa regardless of being aware that the company operates in occupied territory and therefore violating international law. According to the position of the German government, as well as that of the European Union and the United Nations, the situation in occupied Western Sahara is not resolved. Siemens Gamesa’s actions in the occupied territory, like those of other companies, contribute to the consolidation of the Moroccan occupation of the territory. Business activity in the occupied Saharawi territory has been addressed by multiple UN resolutions on the right to self-determination of occupied Western Sahara and the right of its citizens to dispose of its resources.

On the ground, it is almost exclusively an outside elite that benefits from the projects: the operator of the energy parks in Western Sahara and direct business partner of Siemens Energy and ENEL is the company Nareva (owned by the king). The Saharawi themselves have no access to projects on their legitimate territory, especially those living in refugee camps in Algeria since they fled the Moroccan invasion. Instead, Saharawi who continue to live under occupation in Western Sahara face massive human rights violations by the occupying power.

Saharawi living in the occupied territory are aware that energy infrastructure—its ownership, its management, its reach, the terms of its access, the political and diplomatic work it does—mediates the power of the Moroccan occupation and its corporate partners. The Moroccan occupation enters, and shapes the possibilities of, daily life in the Saharawi home through (the lack of) electricity cables. Saharawi understand power cuts as a method through which the occupying regime punishes them as a community, fosters ignorance of Moroccan military manoeuvres, combats celebrations of Saharawi national identity, enforces a media blockade so that news from Western Sahara does not reach “the outside world” and creates regular dangers in their family home. They also acknowledge that renewables are not the problem per se but are a tool for the colonialist kingdom to advance the colonisation in a new form and with news legitimisations from foreign countries. The new projects are being built so fast that the local opposition to them is ineffective. The Saharawi decolonial struggle is deeper, the final goal is liberation and self-determination; they acknowledge that the renewable power plants will be good when managed for the goodwill of the Saharawi in a free SADR. As a fisherman from Laayoune said in an interview about the offshore windmills: “They do not represent anything but a scene of the wind of your land being illegally exploited by the invaders with no benefits for the people”.

People interviewed: Khaled, activist of Juventud Activa Saharaui, El Machi, Saharawi activist, Ahmedna, activist of Juventud Activa Saharaui, former member of Red Ecosocial Saharaui, Youssef, local Saharawi from Laayoune, Ayoub, youth activist from Laayoune injured by police, Khattab, Saharawi journalist (interviewed with Ayoub), Asria Mohamed, Saharawi podcaster based in Sweden.

by DGR News Service | Jan 25, 2021 | Agriculture, Biodiversity & Habitat Destruction, Colonialism & Conquest, People of Color & Anti-racism

In the following piece, Mark relates the population growth to patriarchy, exploitation, and capitalism.

Editor’s note: DGR does not agree with all opinions on this article.

by Mark Behrend

The population of Africa is soaring.

Since 1950, it has grown from 227 million to 1.343 billion — an increase of 590%. Over the same period, South America has grown by 425%, Asia by 330%, and North and Central America by 250%, while Europe has only grown by 35%.

There are many reasons for the disparity, though the basic factors are development, wealth, and education. With development, infant mortality generally goes down and life expectancy increases, driving population up. Development tends to increase prosperity, education, and opportunities, gradually bringing population growth to a halt. Under normal development patterns, this results in a huge population increase when an economy is fueled largely by primary industries. Population growth slows as the economy moves into secondary industries, and levels off in a tertiary economy, where wealth is amassed, service industries emerge, and domestic businesses expand into foreign markets. That’s the upside of industrialization.

The downside is that both sides of this growth curve devastate the natural world.

With an exponential increase in the consumption and depletion of natural resources, degradation of air, land, and water, an ultimately fatal attack on biodiversity, and the exploitation of cultures on the back end of the development curve. Rooted in colonialism, the immediate threat to Africa’s people is that most of the benefits of development are going to European, American, and Chinese corporations. This does not appear likely to change. According to U.N. estimates, populations in North America, Europe, and Southeast Asia are expected to stabilize by 2100, while Africa’s is expected to triple.

Due to a variety of factors, including government inaction, corruption, and poor educational opportunities, birth rates remain high. To state it simply, unschooled girls and women have few options in life but to marry young and have four or more children. Ignorance can lead to the persistence of superstitions and regressive cultural practices, such as female genital mutilation, and beliefs that contraception causes promiscuity, infertility, and various health problems.

A recent news story reported that 10% of girls in Senegal are still subjected to female genital mutilation.

The practice remains common on much of the continent. A Senegalese activist said it continues, mostly among the poor and uneducated, who are afraid to defy old customs. He noted that victims often experience a high rate of lasting pain, along with a much higher than normal incidence of menstrual problems. A woman in favor of FGM, however, disagreed and said.

“If women are having problems, it’s because of contraception.”

The more obvious problem with contraception in Africa is that it is rarely used. The population of Senegal jumped from 2.4 million in 1950 to 16.3 million in 2018 — an increase of 675% in 68 years. On average, that’s the equivalent of adding 10% of a country’s current population every year, in perpetuity. The country with the greatest population growth, however, is Ivory Coast, with an astounding 978% increase over a similar period (2.6 million to 25.7 million, between 1950 and 2018). This can be linked directly to corporate exploitation, as the numbers clearly show.

Since independence in 1960, foreign corporations have virtually transformed Ivory Coast into one giant cocoa plantation, to feed the developed world’s voracious demand for chocolate. In 2019, the world cocoa market was worth over $44 billion, and is projected to top $61 billion by 2027. Along the way, Ivory Coast has become the world’s largest producer, with an estimated 38% of global production. In the process, however, 90% of the country’s forests have been sacrificed, and the illusion of economic growth has driven an unprecedented explosion in the Ivorian census.

Several foreign corporations are responsible for this, the principal offenders being Olam International (Singapore); Barry Callebaut (Switzerland); and the American companies Cargill, Nestle, Mars, and Hershey. They have much to be responsible for.

Capitalism’s guiding principle of creating an ever-growing demand at the lowest possible cost has led to more than rampant deforestation.

According to The Guardian an astounding 59 million children, aged five to 17, are working against their will in sub-Saharan Africa, mostly in agriculture. Due to the refusal of some agencies and governments to include family farms in forced labor statistics, however, estimates of the number of victims vary widely. Fortune Magazine, for instance , puts the number of child laborers in West Africa at “only” 2.1 million. Additional data from the U.S. Department of Labor indicate that over a million children under the age of 12 work in the cocoa industry in Ivory Coast and Ghana, which together produce more than two-thirds of the world’s supply.

Thousands are recruited from even poorer African countries, often with promises of good jobs and free education. Instead, they become victims of what is arguably the world’s largest human trafficking and slavery network. Even those working on family farms are often kept out of school to work in hazardous conditions, with 95% of them reportedly exposed to pesticides, and at risk of injury from using machetes and carrying heavy loads.

Pressured by organized boycotts by Europeans and Americans, the industry pledged in 2001 to reduce child labor 70% by 2020.

Instead, a new report says that since 2010, the number of West African children engaged in forced labor has increased from 31% to 45% of the total childhood population. The reason, again, is the basic mechanism of capitalism. Industry influences consumers to demand more, by producing more and advertising it at a lower price — thus enabling corporations to pay farmers even less. As a result, wholesale prices for cocoa have been cut in half since the 1970s. This has been achieved by paying West African farmers between $.50 and $.84 a day, while the World Bank’s poverty line is $1.90. Hence the 60% rise in cocoa production since 2010, the 45% jump in child labor, and the accelerated pace of deforestation. Farmers are compelled to produce more, just to make the same money they used to make for producing less.

The cocoa industry explains this by saying that it decentralized production (i.e., encouraged family farming rather than corporate plantations) to hold down costs. So, now it can’t meet its child labor goals, because family farms can’t be regulated like factory farms. Corporations call this good economics, while a neutral observer might call it legalized slavery.

A 2019 study, reported by The Guardian, says research indicates that the best way to end child labor is by educating girls and empowering women, in what remain highly patriarchal societies.

There are 18 steps in preparing cocoa for the wholesale market, and women and girls perform 15 of them. This is typical of labor patterns in much of the developing world. And it goes a long way toward explaining the poverty, overpopulation, and environmental destruction that plague the “Third World” — and, by extension, the planet as a whole. In Ivory Coast, the production demands and poverty forced on local communities has also forced roughly a million people to seek their livelihoods by illegally deforesting and farming in national forests and national parks. Recent surveys found that in 13 of 23 of these so-called “protected areas,” once thriving populations of chimpanzees and forest elephants have been totally eliminated.

At the current rate, Ivory Coast’s irreplaceable flora and fauna will soon be gone, along with a carbon sink half the size of Texas. Similar scenarios are playing out across Africa, as global agribusiness becomes more invested in African lands. Incredibly, the Ivorian government’s response has been to pass a law that would effectively put the nation’s forestry protection under corporate control for the next 24 years. The argument behind this fox-guarding-the-henhouse policy is that corporations see the “big picture,” while local farmers only see their own immediate needs. The policy would expel those one million illegal farmers from public lands, with no assistance or other apparent options, apart from migration, starvation, or lives of crime.

Such is the grim reality of corporate resource extraction in nations that were European colonies less than a century ago, and today have become virtual colonies of E.U., U.S., and Chinese business. China now has a huge and ever-growing footprint, both in East Africa and in Latin America. On the surface, Beijing paints this as a “win-win” relationship, with China building “free” infrastructure, and bringing big business to the boondocks.

The reality, however, is a far different story — with pipelines and powerplants crossing the Serengeti, a superhighway across fragile Amazon headwaters, and a rival to the Panama Canal on its way to completion, in Central America’s most environmentally sensitive wetlands. And if supposedly accountable corporations in Western democracies can’t stop child labor in West Africa, what are we to expect from a secretive dictatorship like China?

Who will feed Africa as its population doubles and triples, with much of the farmland now leased to Chinese agribusiness?

How long can Africa’s (or Indonesia’s, or Brazil’s) rich biodiversity survive, with their habitat reduced to a corporate commodity? Who would you pick to win a competition between gorillas, elephants, giraffes, and zebras, on the one hand, and global extraction industries, on the other?

As the monocrop cocoa farms of Ivory Coast become infertile and lose their productivity, the booming population will inevitably face growing poverty, and a very real threat of starvation. That isn’t the “corporate plan,” of course. The corporate plan, as one Ivorian farmer observed, is simply to make as much money as possible as fast as possible. And African farmers either play along, or the cocoa companies find those who will. The cycle thus compels Africans to make more babies to work the land, and then rape the land to feed the babies.

When it comes to Africa, ‘supply and demand’ is merely a sanitized term for ‘slash and burn’. Capitalism has no long-term plan for the continent, because the corporations are beholden to non-African investors back home. Their competitive edge is based on exceeding the year-end dividends of their rivals. From a business standpoint, the practical meaning of the profit motive is to use up the planet as fast as possible, and report it for tax purposes as normal depreciation.

Crazy as it sounds, the long-term plan of industrial civilization is simply to have a good short-term plan.

Corporations are all about the current fiscal year, just as democratic governments are all about the next election cycle. Sensible goals (relatively speaking) may be discussed and agreed to in forums like the Paris Climate Accords. But that all presumes a world working toward a common goal. When the negotiators get back home, however, they’re in a competitive race again. It’s nation against nation, corporation against corporation — the “real world” of year-end reports and election cycles, where those “sensible goals” they agreed to in principle are put off until next year. And “tomorrow,” as the song says, “never comes.”

Such are the economic realities that prompted the International Panel on Biodiversity and Ecosystem Services (IPBES) to project that by 2050, the world will face between 50 million and 700 million food refugees — a polite term for starving people, coming soon to a country near you. IPBES says the most likely number is between 200 and 300 million. At any rate, it will make Europe’s current crisis of African and Asian refugees (along with Latin American migrants fleeing to the United States) look like a picnic in the park, and today’s regional crisis will become tomorrow’s global disaster. Such is the future of corporate capitalism, where the rich plunder the resources of the poor, create a baby boom for cheap labor, and then — when there is no longer any profit in it — abandon both the people and the land.

The destruction can no longer be confined to the developing world.

This time the migrants will follow us home. Indirectly, their barren land will follow us, too — in the form of climate change, sea level rise, and the other unintended consequences of globalization, in what promises to be capitalism’s last century. There is simply nowhere left to run. As Chris Hedges describes it,

“It’s all Easter Island now.”

Returning to the education factor, population experts have long recognized the link between female education and employment opportunities on the one hand, and population stability on the other. Indeed, wherever women and girls have access to higher education, equal job opportunities, and the right to say “no” to having babies, population either stabilizes or decreases slightly.

For proof, one need only look to South Korea, where this otherwise positive formula is creating an economic problem of its own. Women there have achieved relative parity, in both education and employment. But with patriarchy persisting in the home, fewer than half of South Korean women now choose to marry, and the population is plunging.

In places like Senegal, on the other hand, “women’s liberation” is a largely meaningless phrase.

Only 63% of girls there so much as finish primary school, and less than half make it to high school. After all, what do corporate exploiters need with educated masses in the developing world? How could the plunder continue, if the plundered were taught why they’re being plundered, where their resources go, who reaps the profits, and what the developing world is getting in return?

Such are the hard truths behind industrial civilization. Insane as it sounds, increased population and planetary destruction are the inevitable consequences of “progress,” when sustainability and common sense argue for reducing population, minimizing technology and energy needs, replanting forests, and restoring the land. Corporate executives, of course, denounce such sustainable ethics as wild-eyed, radical nonsense. To their thinking, perpetual growth is the only way to avoid economic stagnation and collapse.

Super-techies like Elon Musk of SpaceX and Google’s Larry Page ignore the math, arguing that we can mine the asteroids, colonize Mars, feed a growing population with hydroponic agriculture, and produce endless clean energy and green jobs. (Former U.S. House Speaker Newt Gingrich went so far as to suggest human colonies on the moon. Gingrich apparently wasn’t aware that the moon has a monthly temperature swing of 540° Farenheit, due to its two-week-long days and nights, and total lack of an atmosphere. Mars, meanwhile, has a highly toxic atmosphere, and an average temperature of -67°. Minor details.)

Technological fantasies aside, these so-called leaders leave one question unanswered:

In what school of economics is it taught that when you knowingly and systematically destroy your home planet, you get another one to plunder for free? What part of “there is no Planet B” did they not understand?

Featured image: Al Jazeera

by DGR News Service | Jan 23, 2021 | Human Supremacy

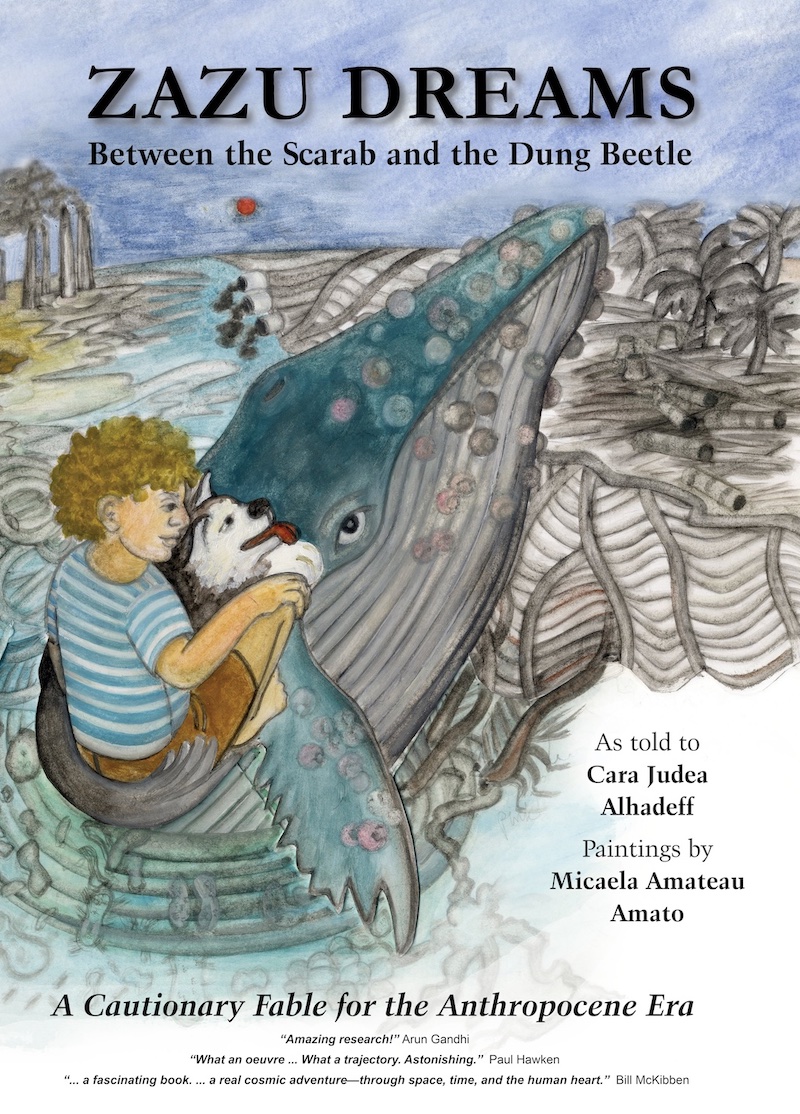

by Cara Judea Alhadeff, PhD

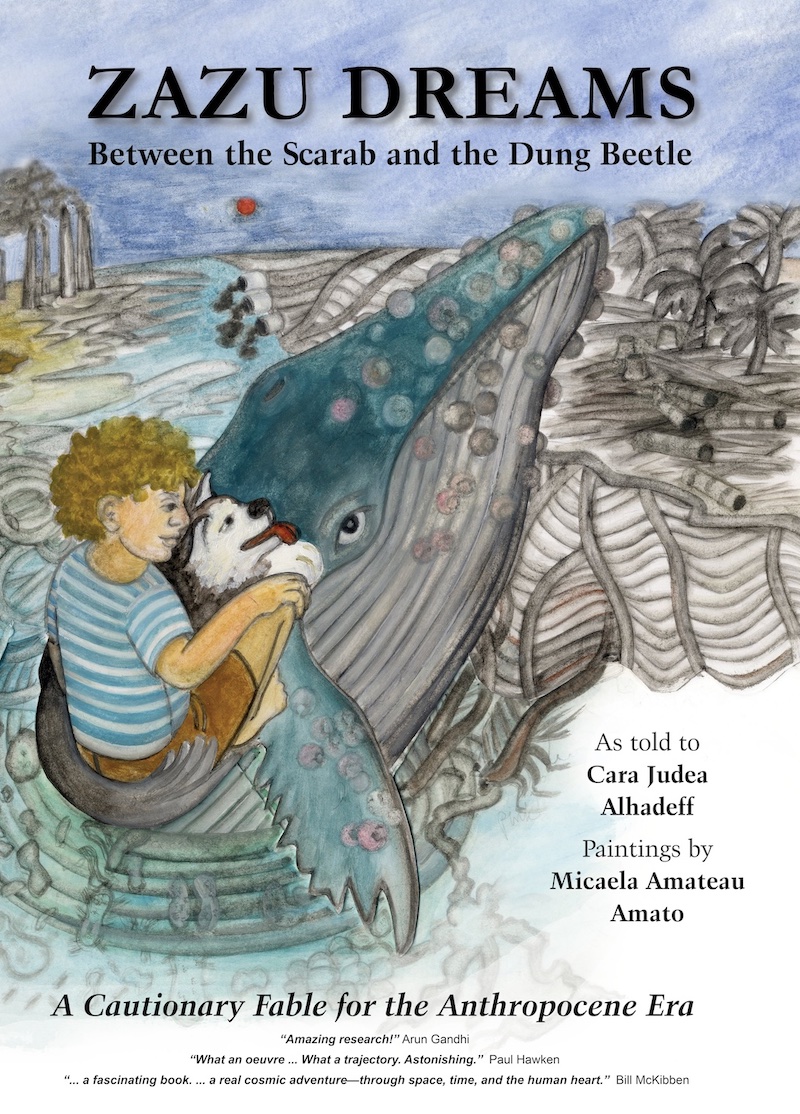

Paintings in this post are by Micaela Amateau Amato from Zazu Dreams: Between the Scarab and the Dung Beetle, A Cautionary Fable for the Anthropocene Era.

The Master’s Tools Will Never Dismantle the Master’s House —Audre Lorde

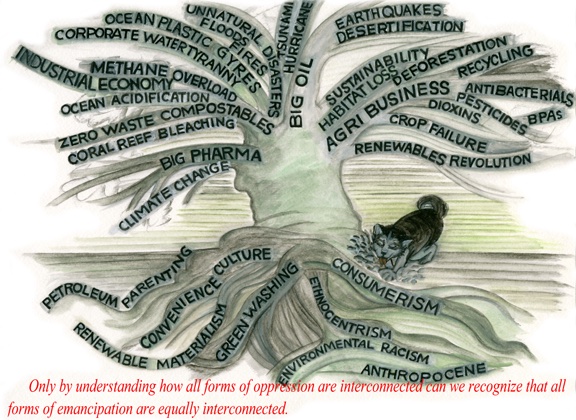

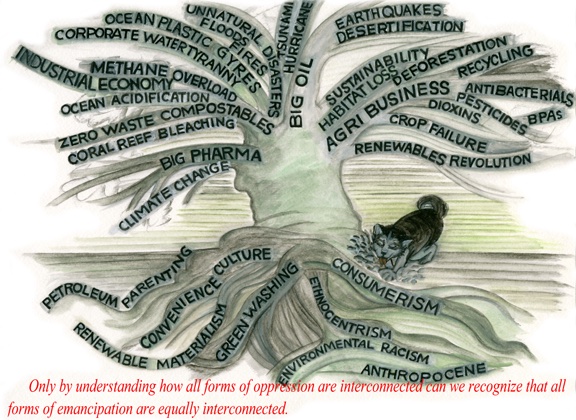

As with our shift from our systemically racist culture to one rooted in mutual respect for multiplicity and difference, we must practice caution during our transition out of our global petroculture. This vigilance should not be based on the motivation, but on the underlying false assumptions and strategies that perceived sustainability and “alternative” agendas offer. The implicit assumptions embedded in the concept of sustainability maintains the status quo. At this juncture of geopolitical, ecological, social, and corporeal catastrophes, we must critically question clean/green solutions such as the erroneously-named Renewable Energies Revolution. I suggest we face both the roots and the implications of how perceived solutions to our climate crisis, like “renewable” energies, may unintentionally sustain ecological devastation and global wealth inequities, and actually divert us from establishing long-term, regenerative infrastructures.

On the surface, sustainability agendas appear to offer critical shifts toward an ecologically, economically, and ethically sound society, but there is much evidence to prove that #1: these structural changes must be accompanied by a psychological shift in individuals’ behavior to effectively shut down consumer-waste convenience culture; and, #2: the core of too many green/clean solutions is rooted in the very essence of our climate crisis: privatized, industrialized-corporate capitalism. For example, in his The Age of Disinformation1, Eric Cheyfitz alerts us: The Green New Deal is a “capitalist solution to a capitalist problem.” It claims to address the linked oppressions of wealth inequity and climate-crisis, yet its proposed solutions avoid the very roots of each crisis.

My challenge is rooted in three interrelated inquiries:

- How are our daily choices reinforcing the very racist systems we are questioning or even trying to dismantle?

- How are the alternatives to fossil-fuel economies and environmental racism reinforcing the very systems we are questioning or even trying to dismantle?

- What can we learn from indigenous philosophies and socialist ecofeminist movements in order to establish viable, sustainable, regenerative infrastructures—an Ecozoic Era?

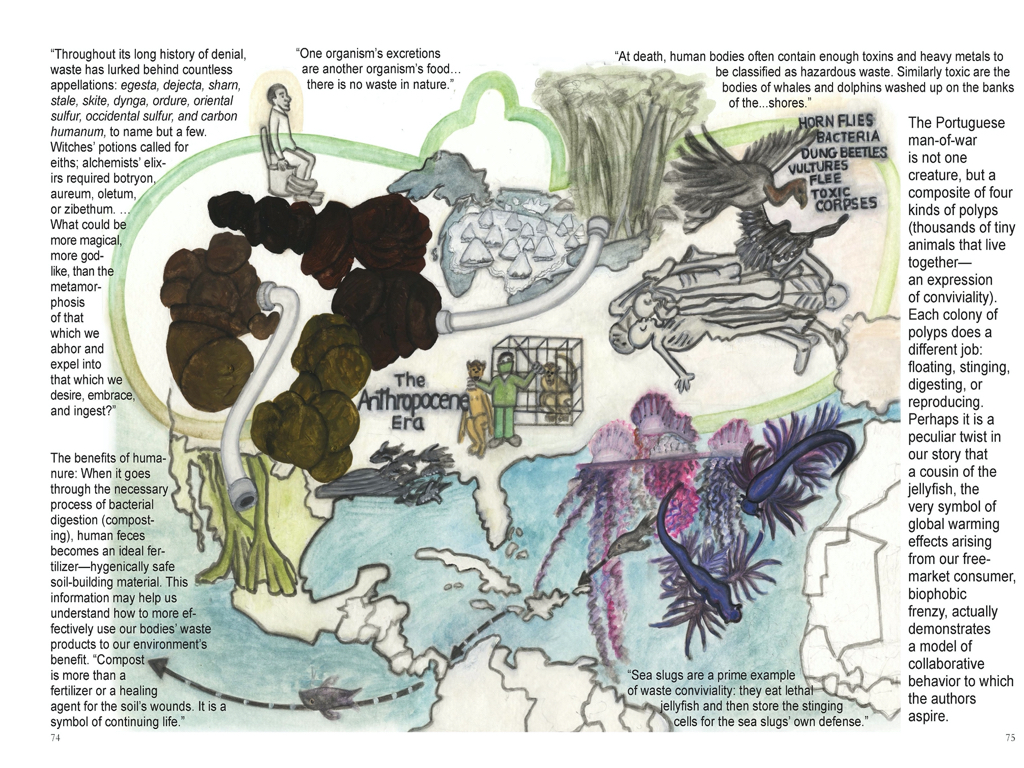

As we transition to supposedly carbon-free electricity, we must be attentive to the ways in which we unconsciously manifest the very racist hegemonies we seek to dislodge; we must be cautious of the greening-of-capitalism that manifests as “green colonialism” through a new dependency on what is falsely identified as “renewable” energies. Currently, human and natural-world habitat destruction are implicit in the mass production and disposal infrastructures of most “renewable energies:” solar, wind, biomass/biofuels, geothermal, ethanol, hydrogen, nuclear, and other ostensible renewables2.

This includes our technocratic petroleum-pharmaceutical addictions that use technologies to create “sustainability.” Even if policy appears to be in alignment with environmental ethics, we are consistently finding that policy change simply replaces one hegemony, one cultural of domination, with another—particularly within the framework of neoliberal globalization. Only when we acknowledge the roots of our Western imperialist crisis, can we begin to decolonize and revitalize all peoples’ livelihoods and their environments.

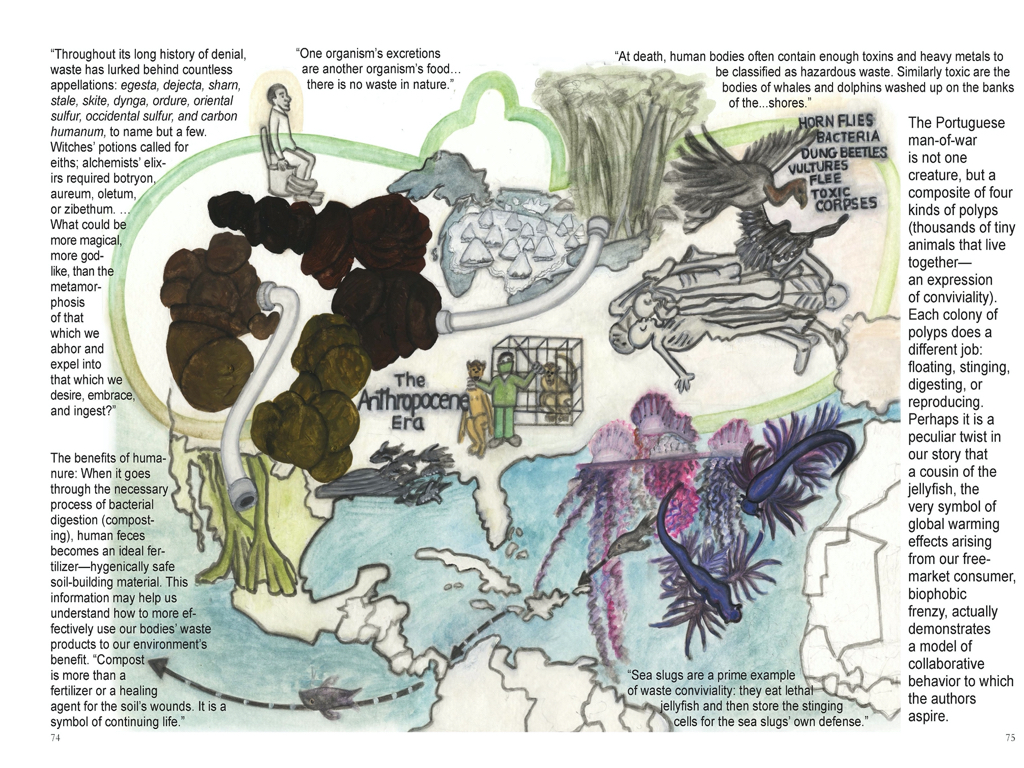

Zazu Dreams: Between the Scarab and the Dung Beetle, A Cautionary Fable for the Anthropocene Era3, my climate justice book that explores the perils of the Anthropocene, challenges cultural habits deeply embedded in our calamitous trajectory toward global ecological and cultural, ethnic collapse. The book’s main character reflects: “We have this crazy idea that anything ‘green’ is good—but we know that there is no clear-cut good and evil. What happens when the very solution causes more problems than the original problem it was supposed to fix?”

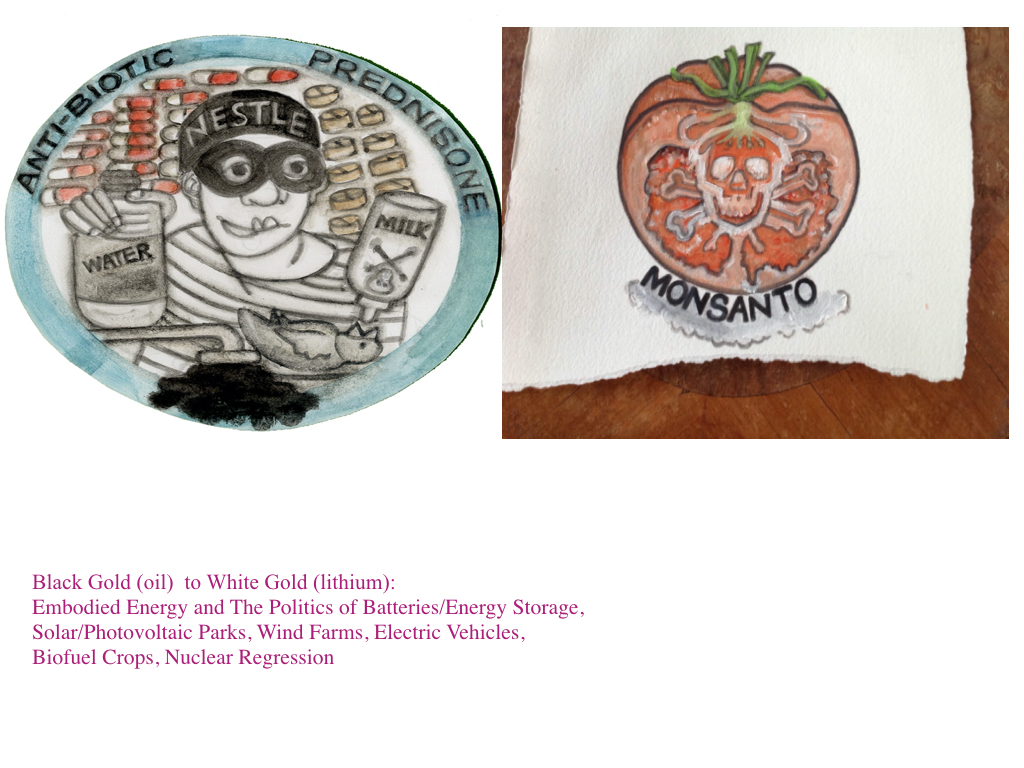

How we measure our ecological footprint4 and global biocapacity is often riddled with paradox—particularly in the face of green colonialism, or what I call humanitarian imperialism5. The litany of our collusion with corporate forms of domination is infinite within the Anthropocene Era (increasingly characterized as the Plasticene). Disinformation campaigns spread by fossil-fuel interests deeply root us in assimilationist consumerism. The Zazu Dreams’ characters witness social and environmental costs of subjugating others through both fossil-fuel-obsessed economies and their “green” replacements. Vaclav Smil warns us of this “Miasma of falsehood.” This implies replacing one destructive socializing norm—petro-pharma cultures sustained by fossil-fuel addicted economics—with another: purportedly “renewable” energies. These energies (I don’t call them renewable, because they are not “renewable” and not carbon-free)6, like fossil-fuels, are rooted in barbaric colonialist extractive industries. Once again, the “solution” is precisely the problem. Greenwashing is a prime example of the ways in which capitalism dictates our alleged freedom. Free market is a euphemism for economic terrorism. The “green economy has come to mean…the wholesale privatization of nature.”7 Consumerism becomes the default for making supposedly ethical choices.

In Deep Green Resistance, Lierre Keith urges us: “We can’t consume our way out of environmental collapse; consumption is the problem”. Even within the 99%, consumers are capitalism. Without convenience-culture/mass consumer-demand, the machine of the profit-driven free market would have to shift gears. We can’t blame oil companies without simultaneously implicating ourselves, holding our consumption-habits equally responsible. How can we insist government and transnational corporations be accountable, when we refuse to curb our buying, using, and disposal habits? We don’t have to go far back in our cross-cultural histories of nonviolent resistance and civil disobedience to learn from world-changing examples of strikes, unions, boycotts, expropriation, infrastructural sabotage, embargoes, and divestment protests.

Yet, most contemporary transition movements are founded in the very system they are trying to dismantle. Our perceived resources, these alternative forms of energy proposed to power our public electrical grids, are misidentified under the misleading misnomers: labels such “renewable”/ “sustainable” / “clean”/ “green”. How is “clean” defined? For whom? There is not a clear division between clean energy and dirty energy/dirty power—clean isn’t always clean. Neoliberal denial of corporeal and global interrelationships instills conformist laws of conduct that continually replenish our toxic soup in which we all live. One perceived solution to help us transition is to create alternatives to fossil fuel-addicted economies, as proposed, for example, through The United States’ proposed Green New Deal and its focus on allegedly “renewable” energies. However well-intentioned, these supposed alternatives perpetuate the violence of wasteful behavior and destructive infrastructures. Even if temporarily abated, they ultimately conserve the original crisis.

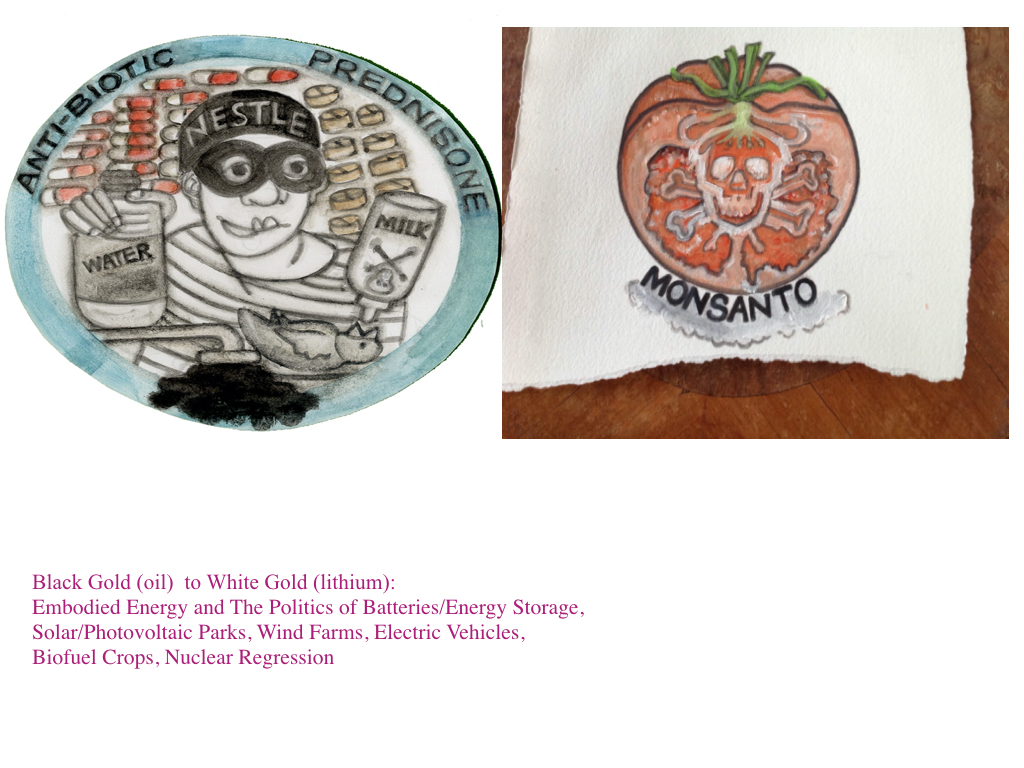

Below I address specific technologies that are falsely identified as “renewable” energy; technologies that actually reinforce the very problem they are trying to solve.

1. Solar/Photovoltaic and Wind Technologies: Given the proposed solutions using industrial solar and wind harvesting, Western imperialism has and will continue to dominate global relations. “Clean energy” easily gets soiled when it is implemented on an industrial scale. Western imperialist practices are implicit in solar cell and storage production (mining and other extractive industries) and disposal infrastructures. Congruently, industrial wind farms—aka: “blenders in the sky,”(chopping up migrating birds & bats) use exorbitant resources to produce and implement (both the wind turbines and their infrastructure), and devastate migrating wildlife (bats and birds, critical to healthy ecosystems and some of whom are endangered species).

Both wind and solar energies require vast quantities of fossil fuels to implement them on a grand scale. As we have seen throughout both California and China (two examples among too many), massive solar-energy sites/solar industrial complexes strip land bare—displacing human populations and migration routes of both wildlife and people for acres of solar fields, substations, and access roads—all of which require incredibly carbon-intensive concrete. Consuming massive tracts of land, 100-1000 times more land area is required for wind and solar, as well as for biofuel energy production than does fossil-fuel production.

2. Hydro-Power Technology: Large-scale dams for hydro-power have also historically had cataclysmic effects on indigenous peoples and their lands. Although macro-hydro, like fracking, has

finally been recognized for its calamitous consequences, perversely, it is still proposed as a viable alternative to fossil-fuel economies.

3. Battery Technology: Let’s begin with a California-based scenario: According to the Union of Concerned Scientists and their Climate Vulnerability Index (CVI) in California, fine particulate pollution harms African-American communities 43% more than predominantly white communities, Latino 39% more, and Asian-American communities 21% more. As if tailpipe emissions are the only humanitarian catastrophe, one “clean solution” is the electric vehicle for public transportation and for personal consumption. Completely ignoring the embodied energy involved, this perceived solution displaces the costs of environmental racism—once again exported out of the US into the global south—in this case to Boliva where lithium (essential for battery production) is primarily mined. Cobalt, also essential to battery production, is mined in the Democratic Republic of the Congo. Like lithium, cobalt’s environmental and humanitarian costs are unconscionable—including habitat destruction, child slavery, and deaths. Eventually, production is followed by solar technology and battery e-waste dispersed throughout Asia, South America, and Africa. Additionally, rarely considered are the fossil-fuel sources used to supply the electricity for those private and public electric vehicles. And, of course most frequently, the poorest US populations work in and live near those coal mines/power plants/fracking stations.

The Renewable Energies Movement claims that our global addiction to oil (“black gold”) should be replaced by lithium (“white gold”). What we are not considering is that extracting lithium and converting it to a commercially viable form consumes copious quantities of water—drastically depleting availability for indigenous communities and wildlife, and produces toxic waste (that includes an already growing history of chemical leaks poisoning rivers, thus people and other animals). Paul Hawken‘s phrase “renewable materialism” counsels us that this hyper-idealized shift from a fossil-fuel paradigm to “renewable” energies is not a solution. Furthermore, these energies are LOW POWER DENSITY: they produce very little energy in proportion to the energy required to institutionalize them.

As the main character in Zazu Dreams prompts: “Even if we find great alternatives to fossil fuels, what if renewable energies become big business and just maintain our addiction to consumption? (…) Replacing tar sands or oil-drills or coal power plants with megalithic ‘green’ energy is not the solution—it just masks the original problem—confusing ‘freedom’ with free market and free enterprise”. We must now act on our knowledge that the renewable “revolution” is dangerously carbon intensive. And, as the authors of Deep Green Resistance caution us: “The new world of renewables will look exactly like the old in terms of exploitation.”

ENDNOTES

- Eric Cheyfitz, Age of Disinformation: The Collapse of Liberal Democracy in the United States. New York: Routledge, 2017.

- Surrogate band-aids that are frequently equal to or worse than what is being replaced include: bioplastics, phthalates replacements, and HFC’s. 1.Compostable disposables, also known as bioplastics, are most frequently produced from GMO-corn monoculture and “composted” in highly restricted environments that are inaccessible to the general public. Due to corn-crop monoculture practices that are dependent on agribusiness’s heavy use of pesticides and herbicides (for example, Monsanto’s Round-Up/glyphosate), compostable plastics are not a clean solution. Depending on their production practices, avocado pits may be a more sustainable alternative. But, the infrastructure and politics of actually “composting” these products are extraordinarily problematic. These not-so eco-friendly products rarely make it into the high temperatures needed for them to actually decompose. Additionally, their chemical compounds cause extreme damage to water, soil, and wildlife. They cause heavy acidification when they get into the water and eutrophication (lack of oxygen) when they leach nitrogen into the soil. 2.The trend to replace Bisphenol A (BPA) led to even more debilitating phthalates in products. 3.Lastly, we now know that hydrofluorocarbons (HFCs), “ozone-friendly” replacements, are equally environmentally destructive as chlorofluorocarbons (CFCs).

- Cara Judea Alhadeff, Zazu Dreams: Between the Scarab and the Dung Beetle, A Cautionary Fable for the Anthropocene Era. Berlin: Eifrig Publishing, 2017.

- The term “carbon footprint” was actually normalized through shame-propaganda by BP’s advertising campaigns. “The carbon footprint sham: A ‘successful, deceptive’ PR campaign,” Mark Kaufman, https://mashable.com/feature/carbon-footprint-pr-campaign-sham/

- Under the guise of the common good and universal values, humanitarian imperialism has emerged as a neo-colonialist method of reproducing the unquestioned status quo of industrialized, “First World” nations. For a detailed deracination of these fantasies (for example, taken-for-granted concepts of equality, poverty, standard of living), see Wolfgang Sachs’ anthology, The Development Dictionary: A Guide to Knowledge as Power. Although the term humanitarian imperialism is not explicitly used, all of the authors explore the hierarchical, ethnocentric assumptions rooted in development politics and unexamined paradigms of Progress. As public intellectuals committed to the archeology of prohibition and power distribution, we must extend this discussion beyond the context of international development politics and investigate how these normalized tyrannies thrive in our own backyard.

- The air and sun are renewable, but giant wind and solar installations are not.

- Jeff Conant, “The Dark Side of the ‘Green Economy,’” Yes! Magazine, August 2012, 63.

![[The Ohio River Speaks] There Must Be Settler Colonialism in the Water](https://dgrnewsservice.org/wp-content/uploads/sites/18/2020/07/settler-colonialism.jpg)