by DGR News Service | May 18, 2021 | Biodiversity & Habitat Destruction, Culture of Resistance, Education, Indigenous Autonomy, Indirect Action, Lobbying, Movement Building & Support, Repression at Home

- The Philippine government has suspended work on a bridge that would connect the islands of Coron and Culion in the coral rich region of Palawan.

- Activists, Indigenous groups and marine experts say the project would threaten the rich coral biodiversity in the area as well as the historical shipwrecks that have made the area a prime dive site.

- The Indigenous Tagbanua community, who successfully fought against an earlier project to build a theme park, say they were not consulted about the bridge project.

- Preliminary construction began in November 2020 despite a lack of government-required consultations and permits, and was ordered suspended in April this year following the public outcry.

This article originally appeared on Mongabay.

Featured image: The Indigenous Tagbanua community of Culion has slammed the project for failing to obtain their permission that’s required under Philippine law. Image by anne jimenez via Wikimedia Commons (CC BY 2.0).

by Keith Anthony S. Fabro

PALAWAN, Philippines — Nicole Tayag, 30, learned to snorkel at 5 when her father took her to the teeming waters of Coron to scout for potential tourist destinations back in 1995. One particularly biodiverse site they found was the Lusong coral garden, southwest of this island town in the Philippines’ Palawan province.

“Even just at the surface, I saw how lively the place was,” Tayag told Mongabay. “We drove our boat for so many times that I remember the passage as one of the places I see dolphins jumping and rays flying up the water. It has inspired me to see more underwater, which led me to my career as a scuba diver instructor now.”

Tayag said she holds a special place in her heart for Lusong coral garden. So when she heard that a government-funded bridge would be built through it, she said was concerned about its impact on the marine environment and tourism industry. Before the pandemic, the 644-hectare (1,591-acre) Bintuan marine protected area (MPA), which covers this dive site, received an average of 3,000 tourists weekly, generating up to 259 million pesos ($5.4 million) in annual revenue. Bintuan is one of the MPAs in the Philippines considered by experts as being managed effectively.

The planned 4.2 billion peso ($88.6 million) road from Coron to the island of Culion would run just over 20 kilometers (12.5 miles), of which only about an eighth would constitute the actual bridge span, according to a government document obtained by Mongabay.

Tayag said they’ve been hearing about the project for 20 years now. “[I] didn’t give much thought about it before, really.” Then, in March this year, Mark Villar, secretary of the Philippine Department of Public Works and Highways (DPWH), posted the project’s conceptual design on his Facebook page.

Tayag said she was shocked that the project was finally going through. “I was even more shocked when I realized it’s so close to historical dive sites and to coral garden,” she said.

Part of President Rodrigo Duterte’s “Build, Build, Build” infrastructure program, construction of the Coron-Culion bridge was scheduled from 2020 to 2023. By November 2020, site clearing had already started in the area designated for the bridge’s access road. But on April 7 this year, the Philippine government announced it was suspending the project to ensure mitigating measures for its environmental impact are in place. This follows a public outcry from academics, civil society groups and nonprofit organizations that say the project is fraught with risks and irregularities.

“Without the concerned citizens and organizations who raised the alarm bell in this project, this would have gone in the way of so many so-called infrastructure projects, which are disregarding our sacred rights to a balanced and healthful ecology,” said Gloria Ramos, head of the NGO Oceana Philippines.

Cultural heritage collapse

Tayag is part of a group, Buklod Calamianes, that initiated an online petition seeking to stop the project. They warned of the damage that the bridge construction could pose to the marine environment, as it would sit within a 5-km (3-mi) radius of seven of the top underwater attractions in Coron and Culion. In addition to the Lusong coral garden, these dive sites include six Japanese shipwrecks from World War II.

“Heavy sedimentation from the construction will settle upon these fragile shipwrecks and potentially cause the collapse of these precious historical underwater sites,” said the petition, which has been signed by more than 19,000 people.

Palawan Studies Center executive director Michael Angelo Doblado said the shipwrecks need to be protected because they’re historically significant heritage sites of local and global importance. “These are evidence that important battles between the American and Japanese air and sea forces happened there.”

Doblado, who is also a professor of history at Palawan State University, said the occurrence of these shipwrecks also highlights that the Calamianes island group that includes Coron and Culion was important for the Japanese forces, whose weapons and other equipment relied on Coron as a source of manganese.

“For these wrecks and its local importance to Coron and its people, that would be left to them to decide,” he told Mongabay. “Is it really important for them historically as a municipality that they will be willing to preserve and protect it? Or will they be willing to sacrifice and give it up as a price for development?

“It also begs the question, if tourism is one of the major earners of Coron, and the proposed bridge … will boost its tourism, is it not ironic that the shipwrecks … will be directly affected by this infrastructure project that is supposed to boost tourism?”

The government had touted the bridge as improving connectivity between the islands to boost the tourism and agriculture sectors, among other benefits. But if it really wants to help the local tourism sector, Doblado said, the government “should have carried out a construction plan that skirts or avoids destroying or affecting these shipwrecks which are famous dive sites and considered as artificial reefs that promote aquatic growth and diversity in that area.”

This would swell the construction cost, he said, but would be vital to saving not only the historical underwater ruins but the marine environment and tourism industry in the long run.

Impact on marine ecosystems

The Philippines has around 25,000 square kilometers (9,700 square miles) of coral reefs, the world’s third-largest extent, and its waters are known for the highest biodiversity of corals and shore fishes, a 2019 study noted. However, the same study showed that the country, located at the apex of the Pacific Coral Triangle, lost about a third of its reef corals over the past decade, and none of the reefs surveyed were in a condition that qualified as “excellent.”

The bridge project added to concerns about the loss of hard-coral cover. Tayag’s group estimated that it would affect 334 hectares (825 acres) of corals, as well as 140 hectares (346 acres) of mangroves. It said the heavy sedimentation, runoff and silt from the construction could cloud the water, blocking the sunlight that’s essential for the growth of the algae that, in turn, nourish the corals.

Coral expert Wilfredo Licuanan from De La Salle University in Manila told Mongabay that the corals and the abundance of sea life they support are quite sensitive to water quality change due to sedimentation. “If you have sediments … their feeding structures are clogged, light penetration is hindered … and then there’s general smothering of life on the sea bottom.”

When corals are undernourished, he said, it can prevent the calcium carbonate accumulation that constitutes reef growth and that takes tens of thousands of years. “If the corals are not able to produce enough calcium carbonate, your reef is not able to continue to grow and … will start eroding,” Licuanan said.

Once that happens, the reefs will not be able to keep up with climate change-induced sea level rise, and will cease to protect the coastlines from big waves and to serve as habitat for many other species, including those that feed fishing communities. “So, all the ecosystem services of coral reefs are dependent on the position of calcium carbonate skeleton,” Licuanan said.

“Any construction activity, be it road building, resort construction, anything of that sort requires that you move earth,” Licuanan said. “You dig, you relocate soil, and so on. And almost always, that means a lot of the soil gets mobilized and is brought to the sea, causing sedimentation.”

That impact to the reef ecosystem will reverberate up to the residents who depend on it for their livelihoods, said Miguel Fortes, a marine scientist and professor at the University of the Philippines. “If you destroy one, you’re actually destroying the other,” he said in an Oceana online forum.

Fortes said it takes about 35 years for damaged coral reefs to recover. That compares to about 25 years for mangroves and a year for seagrass, both of which are useful in mitigating climate change, he said. In Coron and Culion, these ecosystems provide estimated annual economic benefits of 3.7 billion pesos ($77.2 million), on top of the 4.1 billion pesos ($85.2 million) generated by the islands’ recreation zones.

Coron Bay’s fisheries production is an important spawning and nursery ground, said Jomel Baobao, a fisheries management specialist with the nonprofit Path Foundation Inc., one of the partner implementers of the USAID Fish Right project. The five communities adjacent to the bridge project alone stand to benefit from a total estimated yield of 89 million pesos ($1.8 million) annually.

“A USAID-funded larval dispersal study showed that Bintuan area is the sink for larvae that come from different sources, making it a rich nursery ground,” Baobao told Mongabay. He added that Coron Bay serves to funnel larvae from the Sulu Sea and West Philippine Sea, and any disruption to that flow could affect fishing yields in Bintuan and other areas.

“The narrowest portion in the bay located in Bintuan where the bridge will be constructed is significant to water exchange between these two seas,” Baobao said. This might be affected if there will be ecosystem loss or destruction in the area because of the bridge.”

The area’s reefs are home to economically important species such as red grouper, lobster and round scad, as well as giant clams, according to the Bureau of Fisheries and Aquatic Resources. Among the coral species that flourish around the Calamianes island group are two endangered ones: Pectinia maxima and Anacropora spinosa. In the Philippines, the latter is found only in the Calamianes.

No green permits

Preliminary tree cutting and clearing of the road leading to the bridge entrance reportedly began in November 2020, raising fears that it could trigger siltation that could jeopardize the marine park.

In a 2020 paper, Licuanan said that management actions, such as enhanced regulation of road construction on slopes leading to the sea and rivers that open into the sea, and consequent limitations on government infrastructure programs that impinge on these critical areas, are crucial in conserving the country’s remaining coral reefs.

“Road building practices locally are particularly destructive because they [the DPWH and private contractors] rarely prioritize soil conservation,” he told Mongabay.

But despite the recent activity, the project has not received the green light from the Palawan Council for Sustainable Development (PCSD), a provincial government agency. PCSD spokesman John Vincent Fabello told Mongabay that no strategic environmental plan (SEP) clearance has been issued to the DPWH for the project. The clearance would essentially guarantee that the high-impact project is located outside ecologically critical zones like marine parks.

“They [DPWH] don’t have an SEP clearance yet,” Fabello said. “Government big-ticket projects still have to [go] through the SEP clearance system of the PCSD. Administrative fines shall be imposed if building commences without the necessary clearance and permits from PCSD and related agencies.”

The Department of Environment and Natural Resources (DENR) said it will also require the DPWH to undertake an environmental impact assessment to obtain an environmental compliance certificate and tree cutting permit for the project. “Government projects will still go through the permitting; you have to follow the process … but it will be faster,” said DENR regional director Maria Lourdes Ferrer.

The DPWH confirmed it had not undertaken the required public consultations, feasibility study, or permit applications prior to the start of construction activities. DPWH regional director Yolanda Tangco said they fast-tracked the construction work because the initial 250 million pesos ($5.2 million) in project funding released to the agency in 2020 would have to be returned to the treasury if it was not spent within two years.

Fortes said this reasoning is unacceptable because projects should not only be politically expedient but also based on scientific evidence and actual user needs.

“To me, this means money still supersedes more vital imperatives [such as] cultural and ecological,” he said. “Poor planning is evident here because it entails huge sacrifices.”

Tangco said her office expects to receive additional construction funding for 2021 to 2023 from the national government. “But if we have decided not to continue it, we will remove it [in our proposal]. Most probably, we will revert the funding and terminate the contract,” she said.

She added that in the feasibility study expected to be completed in July 2021, the public works office is considering two more route options: “Our alignment isn’t fixed. If we can find an alignment with lesser impacts to the environment and Indigenous people, we will pursue that and issue variation and change orders [to the contractor].”

Indigenous communities fight back

The Indigenous Tagbanua community of Culion has slammed the project for failing to obtain their permission through a process of free, prior and informed consent (FPIC), required under Philippine law.

“We don’t want that bridge here because we fear that it will affect many — our seas, our livelihoods, our lands we inherited from our ancestors,” Indigenous federation chairman Larry Sinamay, who organized a rally on April 5, told Mongabay. “Where would we get our food when our place is destroyed by this project?”

“The social and sacred value of this traditional space to the Tagbanua should be respected by every member of the community, even us outsiders, tourists and developers,” said Kate Lim, an archaeologist who has conducted studies in the region. “The concept of ancestral domain is that it’s communal and utilized by everyone and not just by one sector only.”

In a letter dated March 31, the federation of 24 Tagbanua communities appealed to the national government to halt the project’s preliminary construction activities, pending impact assessments.

“If we receive no response to our plea, we will be forced to seek legal remedies to fight for our Indigenous rights provided under the Philippine Constitution, Indigenous Peoples’ Rights Act, and other laws related to environment and natural resources,” the federation said at the time.

The Tagbanuas have experience standing up to projects they see as imperiling their environment and culture. In 2017, they banded together to stop a proposed Nickelodeon theme park, which also lacked the necessary scientific studies, consultations and permits.

“Even if we are battling a pandemic, we can’t forget that our battle to protect Palawan’s natural resources must go on,” said Anna Oposa, executive director of Save Philippine Seas, who joined the Tagbanuas in fighting the Nickelodeon project. “The Tagbanua IPs have the experience and power to block or at the very least significantly delay this potentially destructive project and come to a consensus with other stakeholders.”

While the public pressure has prompted the government to suspend the project, the community says it isn’t dropping its guard.

“In a time of pandemic and lockdowns, projects are easily sneaked in and started out of the public’s eye who are confined in their homes,” Tayag said.

“We are closely monitoring these bateltelan [hard-headed] officials. We trust that the government offices looking into this project will do what is right and not just focus on its ‘good intention.’”

Citations:

Licuanan, W. Y., Robles, R., & Reyes, M. (2019). Status and recent trends in coral reefs of the Philippines. Marine Pollution Bulletin, 142, 544-550. doi:10.1016/j.marpolbul.2019.04.013

Licuanan, W. Y. (2020). Current management, conservation, and research imperatives for Philippine coral reefs. Philippine Journal of Science, 149(3), ix-xii. Retrieved from https://philjournalsci.dost.gov.ph/publication/regular-issues/past-issues/98-vol-149-no-3-september-2020/1225-current-management-conservation-and-research-imperatives-for-philippine-coral-reefs-2

by DGR News Service | May 15, 2021 | Alienation & Mental Health, Human Supremacy, Listening to the Land, Mining & Drilling, Toxification

This is an edited transcript of this Deep Green episode. Featured image: “Watershed” by Nell Parker.

I’ve been thinking a lot lately about aquifers.

As we know, this culture is drawing down aquifers around the world. Aquifers are underground rivers, lakes, seeps – it’s underground water and they can be anywhere from just six inches below the surface down to about 10,000 feet and they are being drawn down around the world.

We’ve heard of the Ogallala aquifer – it’s is an absolutely huge aquifer that has been used for irrigation for the last hundred years – it’s being drawn down terribly. Aquifers can recharge but it’s very slow. The other thing that’s happening to aquifers around the world is that they’re being poisoned – sometimes unintentionally as people pollute the ground and it leaches down into the groundwater and sometimes intentionally as in fracking or fracking for geothermal. The latter are “green”; where they put chemicals down and then explode the rocks into a billion pieces so they can frack out the oil or they can then allow the heated water to escape to the surface which they use to generate electricity. When you poison an aquifer – if recharging an aquifer takes a long, long, long, long, long time – detoxifying an aquifer takes that same amount of time, longer. I don’t even know how long it takes before an aquifer would become detoxified. It’s all a very, very, very stupid idea.

I’ve said many times that my environmentalism – I love the natural world, I love bears, I love salmon and I love trees – but my environmentalism also emerges from a fundamental conservatism, that I think it’s really, really, stupid to create a mess that you can’t fix. You know, if you drive salmon extinct that’s a mess you can’t fix because you can’t bring them back, and if you toxify an aquifer you’ve created a mess that you can’t fix. This is something I learned very young from my mom. If you make a mess you clean it up and if you cannot clean up that mess you don’t make it in the first place.

None of that is the point on why I want to bring this up. There are a lot of studies that have been done about who lives in these aquifers. They make up about 40% of the microbial habitat on the planet and account for I think 20% of the microbial population on the planet – viruses, archaea, bacteria and also fungi down to maybe a hundred feet; fungi don’t go much lower in the aquifer. Without bacteria we would all die almost instantly. Bacteria do the real work of life on this planet.

There have been a fair number of studies done on who lives down there;

and I have seen a fair number of people express concern over the drawdown of aquifers; and this concern is always expressed in terms of if “we keep drawing it down we can’t draw down more”. “If we empty the Ogallala aquifer how are we going to irrigate?” It’s always self-centered. The same with toxification; “if we toxify this water then when we put in a well our water is going to catch on fire or we won’t be able to drink the water.”

They may exist but I have yet to see one person, one person, in the entire world express concern for the aquifer communities as communities themselves. That person may exist but I’ve never heard of them and if that person does care about those communities as communities, as biomes – I mean there are people who say “gosh I love the grasslands” and “I wish the grasslands were there because I love buffalo and I love buffalo for their own sake”; “I love beavers for their own sake”; “I love old growth forests for their own sake.” I’ve never heard anybody say the Ogallala aquifer should not be drained because it is a biome, a community, of its own and has the right to exist for its own sake without us drawing it down and without us toxifying it. If anybody does care about them and works on these issues, I would love to interview you; but this is not an ad for that. I want to raise the issue.

It took me years of thinking about aquifers before it occurred to me that they’re their own communities

and now I’m the only person I know who thinks about this – that when they’re drawn out that’s harming those communities. I want for that to start to become part of the public conversation about aquifers – that not only do aquifers provide water for us and for everybody else; not only do aquifers provide hugely – here’s one thing, when an aquifer collapses the soil subsides above it and I just read an article a few days ago about how that that causes tremendous harm to infrastructure; it’s like and..? AND..? And how about the ecological infrastructure? How about the communities who live down there? How about the surface native communities? I want to make it part of the public conversation that aquifers exist for their own sake. They have their own beingness and their own communities and those communities are just as important to them as your community is to you and my community is to me.

by DGR News Service | May 13, 2021 | Biodiversity & Habitat Destruction, Strategy & Analysis, The Problem: Civilization, Toxification

The aquatic food web has been seriously compromised by chemical pollution and climate change.

This article originally appeared on Climate and Capitalism

A report released today by the International Pollutants Elimination Network (IPEN) and the National Toxics Network (NTN) says that rising levels of chemical and plastic pollution are major contributors to declines in the world’s fish populations and other aquatic organisms.

Dr. Matt Landos, co-author of the report, says that many people erroneously believe that fish declines are caused only by overfishing. “In fact, the entire aquatic food web has been seriously compromised, with fewer and fewer fish at the top, losses of invertebrates in the sediments and water column, less healthy marine algae, coral, and other habitats, as well as a proliferation of bacteria and toxic algal blooms. Chemical pollution, along with climate change itself a pollution consequence, are the chief reasons for these losses.”

Aquatic Pollutants in Oceans and Fisheries documents the numerous ways in which chemicals compromise reproduction, development, and immune systems among aquatic and marine organisms. It warns that the impacts scientists have identified are only likely to grow in the coming years and will be exacerbated by a changing climate.

As co-author Dr. Mariann Lloyd-Smith points out, the production and use of chemicals have grown exponentially over the past couple of decades. “Many chemicals persist in the environment, making environments more toxic over time. If we do not address this problem, we will face permanent damage to the marine and aquatic environments that have nourished humans and every other life form since the beginning of time.”

The report identifies six key findings:

- Overfishing is not the sole cause of fishery declines. Poorly managed fisheries and catchments have wrought destruction on water quality and critical nursery habitat as well as the reduction and removal of aquatic food resources. Exposures to environmental pollutants are adversely impacting fertility, behavior, and resilience, and negatively influencing the recruitment and survival capacity of aquatic species. There will never be sustainable fisheries until all factors contributing to fishery declines are addressed.

- Chemical pollutants have been impacting oceanic and aquatic food webs for decades and the impacts are worsening. The scientific literature documents man-made pollution in aquatic ecosystems since the 1970s. Estimates indicate up to 80% of marine chemical pollution originates on land and the situation is worsening. Point source management of pollutants has failed to protect aquatic ecosystems from diffuse sources everywhere. Aquaculture is also reaching limits due to pollutant impacts with intensification already driving deterioration in some areas, and contaminants in aquaculture feeds affecting fish health.

- Pollutants including industrial chemicals, pesticides, pharmaceuticals, heavy metals, plastics and microplastics have deleterious impacts to aquatic ecosystems at all trophic levels from plankton to whales. Endocrine disrupting chemicals, which are biologically active at extremely low concentrations, pose a particular long-term threat to fisheries. Persistent pollutants such as mercury, brominated compounds, and plastics biomagnify in the aquatic food web and ultimately reach humans.

- Aquatic ecosystems that sustain fisheries are undergoing fundamental shifts as a result of climate change. Oceans are warming and becoming more acidic with increasing carbon dioxide deposition. Melting sea ice, glaciers and permafrost are increasing sea levels and altering ocean currents, salinity and oxygen levels. Increases in both de-oxygenated ‘dead zones’ and coastal algal blooms are being observed. Furthermore, climate change is re-mobilizing historical contaminants from their ‘polar sinks.’

- Climate change and chronic exposures to pesticides all can amplify the impacts of pollution by increasing exposures, toxicity and bioaccumulation of pollutants in the food web. Methyl mercury and PCBs are among the most prevalent and toxic contaminants in the marine food web.

- We are at the precipice of disaster, but have an opportunity for recovery. Progress requires fundamental shifts in industry, economy and governance, the cessation of deep-sea mining and other destructive industries, and environmentally sound chemical management, and true circular economies. Re-generative approaches to agriculture and aquaculture are urgently required to lower carbon, stop further pollution, and begin the restoration process.

by DGR News Service | May 7, 2021 | Biodiversity & Habitat Destruction, Colonialism & Conquest, Direct Action, Indigenous Autonomy, Mining & Drilling, Movement Building & Support, Noncooperation, Protests & Symbolic Acts, Repression at Home, Toxification, White Supremacy

Original Press Release

Relatives,

Together we are powerful. Since the #DefundLine3 campaign launched in February, bank executives have received more than 700,000 emails, 7,000 calendar invites and 3,000 phone calls, demanding that they stop funding Line 3. There have been protests at bank branches in 16 states. Collectively, we’ve raised more than $70,000 for those on the frontlines.

Now, we’re pulling all of that energy together for one powerful, coordinated day of action.

There are already actions confirmed in more than 40 US cities ― in New York, DC, San Francisco, Chicago, Boston and more ― as well as in the UK, France, Holland, Switzerland, Costa Rica, Canada and Sierra Leone.

If there isn’t an action near you, organize one! Actions can be small. Going to a local bank branch with your friend to deliver a letter or petition can be a powerful action. Actions can be large. Think hundreds of people shutting down the streets outside of a bank’s headquarters.

On the frontlines, more than 240 people have now been arrested for taking bold direct action to stop the construction of Line 3.

Just a few weeks ago, Indigenous Water Protectors sang and prayed inside of a waaginogaaning, the traditional structure of Anishinaabe peoples, as allies locked to each other around the lodge, blocking Line 3 construction for hours.

After they were arrested, the Indigenous Water Protectors were strip-searched, shackled and kenneled ― for nonviolent misdemeanors. Meanwhile, Enbridge has spent hundreds of thousands of dollars on riot gear, tear gas, and weapons for local militarized police forces that are regularly surveilling and harrassing nonviolent Water Protectors.

-Simone Senogles

P.S. Want to learn more about the #DefundLine3 campaign? Check out

this blog or

this blog from Tara Houska, founder of the Giniw Collective.

by DGR News Service | May 4, 2021 | Biodiversity & Habitat Destruction, Climate Change, Listening to the Land, Mining & Drilling, Movement Building & Support, Toxification

In this article Rebecca Wildbear talks about how civilization is wasting our planet’s scarce water sources for mining in its desperate effort to continue this devastating way of life.

By Rebecca Wildbear

Nearly a third of the world lacks safe drinking water, though I have rarely been without. In a red rock canyon in Utah, backpacking on a week-long wilderness training in my mid-twenties, it was challenging to find water. Eight of us often scouted for hours. Some days all we could find to drink was muddy water. We collected rain water and were grateful when we found a spring.

Now water is scarce, and the demand for it is growing. Globally, water use has risen at more than twice the rate of population growth and is still increasing. Ninety percent of water used by humans is used by industry and agriculture, and when groundwater is overused, lakes, streams and rivers dry up, destroying ecosystems and species, harming human health, and impacting food security. Life on Earth will not survive without water.

In the Navajo Nation in Arizona, Utah, and New Mexico, a third of houses lack running water, and in some towns, it is ninety percent. Peabody Energy Corporation, the largest coal producer and a Fortune 500 company, pulled so much water from the Navajo aquifer before closing its mining operation that many wells and springs have run dry. Residents now have to drive 17 miles to wait in line for an hour at a communal well, just to get their drinking water.

Worldwide, the majority of drinkable water comes from underground reservoirs called aquifers. Aquifers feed streams, lakes, and rivers, but their waters are finite. Large aquifers exist beneath deserts, but these were created eons ago in wetter times. Expert hydrologists say that like oil, once the “fossil” waters of ancient reservoirs are mined, they are gone forever.

Peabody’s Black Mesa Mine extracted, pulverized, and mixed coal with water drawn from the Navajo aquifer to form a slurry. This was sent along a 273-mile-long pipeline to the Mojave Generating Station in Laughlin, Nevada, to power Los Angeles. Every year, the mine extracted 1.4 billion gallons (4,000+ acre feet) of water from the aquifer, an estimated 45 billion gallons (130,000+ acre feet) in all.

Pumping out an aquifer draws down the water level and empties it forever. Water quality deteriorates and springs and soil dry out. Agricultural irrigation and oil and coal extraction are the biggest users of waters from aquifers in the U.S. Some predict that the Ogallala aquifer, once stretching beneath five mid-western states, may be able to replenish after six thousand years of rainfall.

Rain is the most accurate measure of available water in a region, yet over-pumping water beyond its capacity to refill is widespread in the western U.S. and around the world. The Middle East ran out of water years ago—it was the first major region in the world to do so. Studies predict that two thirds of the world’s population are at risk of water shortages by 2025. As ground water levels fall, lakes, rivers, and streams are depleted, and the land, fish, trees, and animals die, leaving a barren desert.

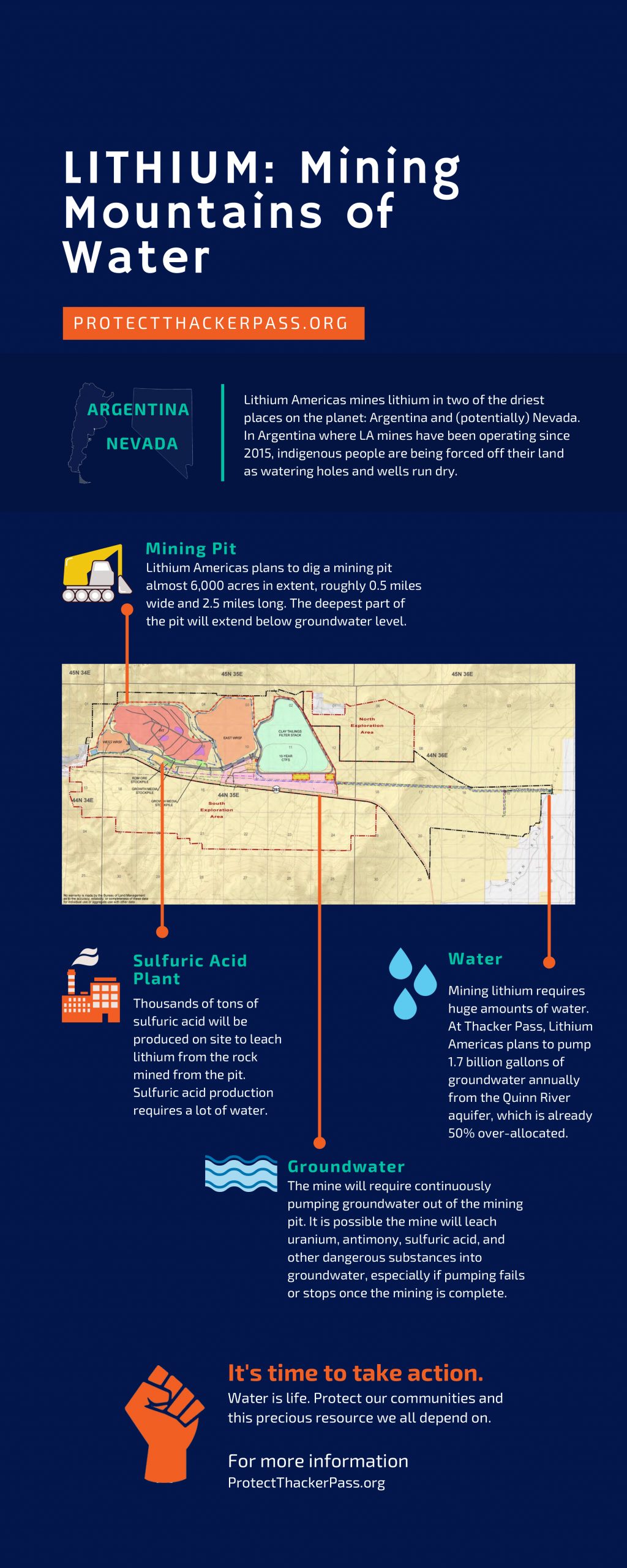

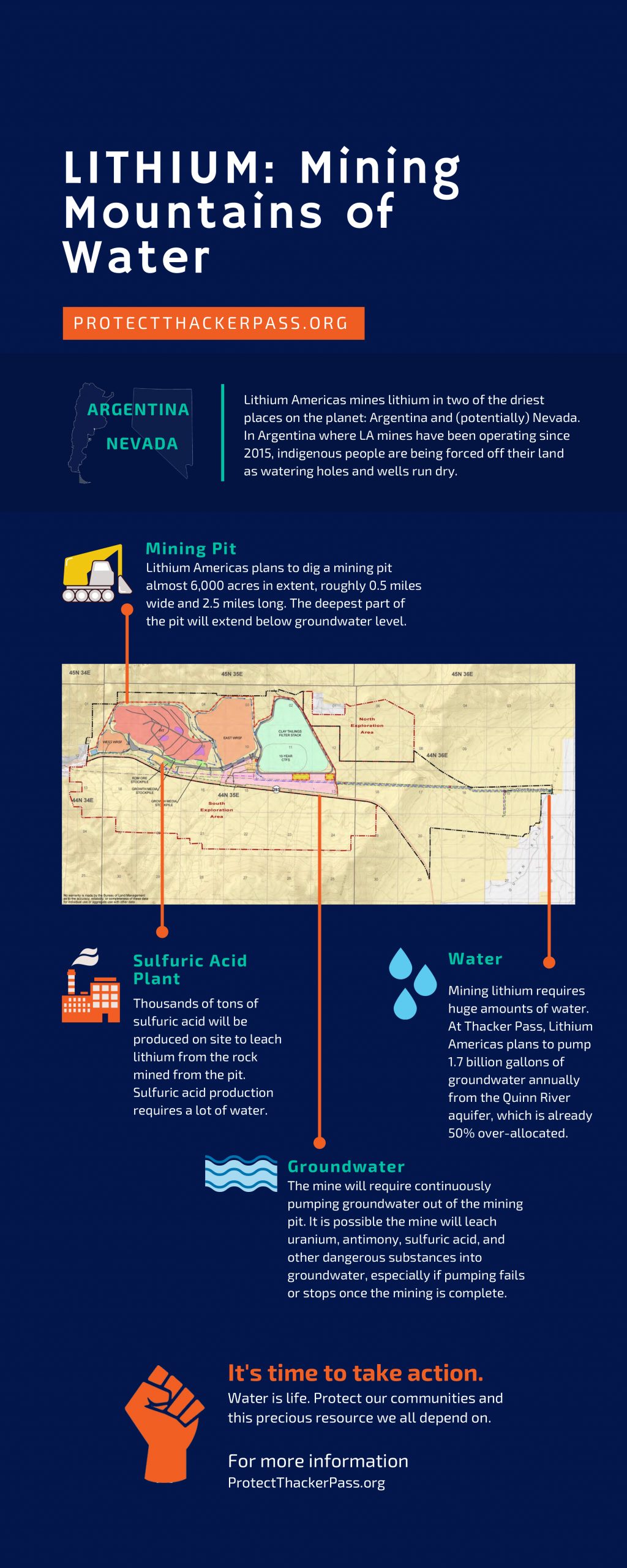

Mining in the Great Basin

The skyrocketing demand for lithium, one of the minerals needed for the production of electric cars, is based on the misperception that green technology helps the planet. Yet, as Argentine professor of thermodynamics and lithium mining expert Dr. Daniel Galli said at a scientific meeting, lithium mining is “really mining mountains of water.” Lithium Americas plans to pump massive amounts of water—up to 1.7 billion gallons (5,200 acre feet) annually—from an aquifer in the Quinn River Valley in Nevada’s Great Basin, the largest desert in the United States.

Thacker Pass, the site of the proposed 1.3 billion dollar open-pit lithium mine, would pump 1,200 acre feet more water per year than Peabody Energy Corporation extracted from the Navajo aquifer. Yet, the Quinn River aquifer is already over-allocated by fifty percent, and more than 10 billion gallons (30,000 acre feet) per year. Nevada is one of the driest states in the nation, and Thacker Pass is only the first of many proposed lithium mines in the state. Multiple active placer claims (7,996) have been located in 18 different hydrographic basins.

Deceit about water fuels these mines. Lithium Americas’ environmental impact assessment is grossly inaccurate, according to hydrologist Dr. Erick Powell. By classifying year-round creeks as “ephemeral” and underreporting the flow rate of 14 springs, Lithium Americas is claiming there is less water in the area than there actually is. This masks the real effects the mine would have—drying up hundreds of square miles of land, drawing down the groundwater level, sucking water from neighboring aquifers—all while claiming its operations would have no effect.

Peabody Energy Corporation’s impact assessment similarly misrepresented how their withdrawals would harm the Navajo aquifer. Peabody Energy used a flawed method to measure the withdrawals, according to former National Science Research Fellow Daniel Higgins. Now Navajo Nation wells require drilling down 2,000–3,000 feet, and the water is depressurized and slow to flow to the surface.

Thacker Pass lithium mine would pump groundwater at a disturbing rate, up to 3,250 gallons per minute. Once used, wastewater would contaminate local groundwater with dangerous heavy metals, including a “plume” of antimony that would last at least 300 years. Lithium Americas plans to dig the mine deeper than the groundwater level and keep it dry by continuously pumping water out, but when the pumping stops, groundwater would seep back in, picking up the toxins.

It hurts me to think about this. I imagine water being rapidly extracted from my own body, my bloodstream poisoned. The best tasting water rises to the surface when it is ready, after gestating as long as it likes in the dark Earth. Springs are sacred. When I feel welcome, I place my lips on the earthy surface and fill my mouth with their sweet flavor and vibrant texture.

Mining in the Atacama Desert

Thirteen thousand feet above sea level, the indigenous Atacamas people live in the Atacama Desert, the most arid desert in the world and the driest place on Earth. For millennia, they have used their scarce supply of water and sparse terrain carefully. Their laws and spirituality have always been intertwined with the health and well-being of the land and water. Living in mud-brick homes, pack animals, llama and alpaca, provide them with meat, hide, and wool.

But lithium lies beneath their ancestral land. Since 1980, mining companies have made billions in the Salar de Atacama region in Chile, where lithium mining now consumes sixty-five percent of the water. Some local communities need to have water driven in, and other villagers have been forced to abandon their settlements. There is no longer enough water to graze their animals. Beautiful lagoons hundreds of flamingos call home have gone dry. The birds have disappeared, and the ground is hard and cracked.

In addition to the Thacker Pass mine proposal, Lithium Americas has a mine in the Atacama Desert, a joint Canadian-Chilean venture named Minera Exar in the Cauchari-Olaroz basin in Jujuy, Argentina. Digging for lithium began in Jujuy in 2015, and there is already irreversible damage, according to a 2018 hydrology report. Watering holes have gone dry, and indigenous leaders are scared that soon there will be nothing left.

Even more water is needed to mine the traces of lithium found in brine than in an open-pit mine. At the Sales de Jujuy plant, the wells pump at a rate of more than two million gallons per day, even though this region receives less than four inches of rain a year. Pumping water from brine aquifers decreases the amount of fresh groundwater. Freshwater refills the spaces emptied by brine pumping and is irreversibly mixed with brine and salinized.

The Sanctity of Water

As a river guide, I live close to water. Swallowed by its wild beauty, I am restored to a healthier existence. Far from roads, cars, and cities, I watch water swirl around rocks or ripple over sand. I merge with its generous flow, floating through mountains, forest, or canyon. Rivers teach me how to listen to the currents—whether they cascade in a playful bubble, swell in a loud rush, or ebb in a gentle silence—for clues about what lies ahead.

The indigenous Atacamas peoples understand that water is sacred and have purposefully protected it for centuries. Rather than looking at how nature can be used, our culture needs to emulate the Atacamas peoples and develop the capacity to consider its obligations around water. Instead of electric cars, what we need is an ethical approach to our relationship with the land. Honoring the rights of water, species, and ecosystems is the foundation of a sustainable society. Decisions can be made based on knowledge of the land, weather patterns, and messages from nature.

For millennia, indigenous peoples have perceived water, animals, and mountains as sentient. If humans today could recognize their intelligence, perhaps they would understand that underground reservoirs have a value and purpose, beyond humans. When I enter a cave, I am walking into a living being. My eyes adjust to the dark. Pressing my hand against the wall, I steady myself on the uneven ground, hidden by varying amounts of water. Pausing, I listen to a soft dripping noise, echoing like a heartbeat as dew slides off the rocks. I can almost hear the cave breathing.

The life-giving waters of aquifers keep everything alive, but live unseen under the ground. As a soul guide, I invite people to be nourished by the visions of their dreams, a parallel world that is also seemingly invisible. Our dominant culture dismisses the value of these perceptions, just as it usurps water by disregarding natural cycles. Yet to create a sustainable world, humans need to be able to listen to nature and their dreams. The depths of our souls are inextricably linked to the ancient waters that flow underground. Dreams arise like springs from an aquifer, seeding our visionary potential, expanding our consciousness, and revealing other ways to live, radically different than empire.

Water Bearers

I set my backpack down on a high sandstone cliff overlooking a large watering hole. Ten feet below the hole, the red rock canyon drops into a much larger pool. My friend hikes down to it, filling her cookpot with water. She balances it atop her head on the way up, moving her hips to keep the pot steady. Arriving back, she pours the water into the smaller hole from which we drink and returns to the large pool to gather more.

Women in all societies have carried water throughout history. In many rural communities, they still spend much of the day gathering it. Sherri Mitchell of the Penobscot Nation calls women “the water bearers of the Universe.” The cycles in a woman’s body move in relation with the Earth’s tides, guiding them to nourish and protect the waters of Earth. We all need to become water bearers now.

Indigenous peoples, who have always been the Earth’s greatest defenders, protect eighty percent of global diversity, even though they comprise less than five percent of the world’s population. They understand water is sacred, and the world’s groundwater systems must be defended. For six years, indigenous peoples have been fighting to prevent lithium mining in the Salinas Grandes salt flats, in Jujuy, Argentina. Five hundred indigenous people camped on the land with signs: “No to lithium. Yes, to water and life in our territories.”

In February 2021, President Biden signed executive orders supporting the domestic mining of “critical” minerals like lithium, but two lawsuits, one by five Nevada-based conservation groups, have been filed against the Bureau of Land Management for approving the Thacker Pass lithium mine. Environmentalists Max Wilbert and Will Falk are organizing a protest to protect Thacker Pass. Local residents, including Northern Paiute and Western Shoshone peoples, are speaking out, fighting to protect their land and water.

We can see when a river runs dry, but most people are not aware of the invisible, slow-burning disaster happening under the ground. Some say those who oppose lithium mining should give up cell phones. If that is true, perhaps those who favor mines should give up drinking water. Protecting water needs to be at the center of any plan for a sustainable future.

The “fossil water” found in deserts should be used only in emergency, certainly not for mining. Sickened by corporate water grabbing, I support those trying to stop Thacker Pass Lithium mine and aim to join them. The aquifers there have nurtured so many for so long—eagles, pronghorn antelope, mule deer, old-growth sagebrush, hawks, falcons, sage-grouse, and Lahontan cutthroat trout. I pray these sacred wombs of the Earth can live on to nourish all of life.

For more on the issue: