by DGR News Service | Jun 25, 2021 | Biodiversity & Habitat Destruction, Colonialism & Conquest, Mining & Drilling

This article originally appeared in The Conversation. Featured image: Sea turtle

Editor’s note: The statement in the article’s headline –that the temptation of allowing deep sea mining(DSM) “could be a problem”– seems ironic. There is no doubt that deep sea mining is extremely dangerous and destructive to oceanic ecosystems which are already serverly stressed by overfishing and global warming. Apart from that, we all know that most of the profit will go to multinational cooperations, not to the island’s inhabitants.

Sue Farran, Newcastle University

While most Pacific Island nations have escaped the worst of COVID-19, a cornerstone of their economies, tourism, has taken a big hit. By June 2020, visitor arrivals in Fiji, Samoa, Tonga and Vanuatu had completely ceased, as borders were closed and even internal travel restricted. In Fiji, where tourism generated about 40% of GDP before the pandemic, the economy contracted by 19% in 2020.

One economic alternative lies just offshore. The Clarion-Clipperton Zone (CCZ) is a deep-sea trench spanning 4.5 million square kilometres in the central Pacific Ocean between Hawaii and Mexico. On its seabed are potato-sized rocks called polymetallic nodules which contain nickel, copper, cobalt and manganese. These formed over centuries through the accumulation of iron and manganese around debris such as shells or sharks’ teeth.

There are estimated to be around 21 billion tonnes of manganese nodules in this trench alone, and demand for these metals is likely to skyrocket as the world ramps up the development of batteries for electric vehicles and renewable power grids.

While much of the CCZ lies beneath the high seas where no single state has control, it’s adjacent to the exclusive economic zones of several Pacific island states, including the Cook Islands, Kiribati, Nauru and Tonga. Lacking the means to search for the metals themselves, these states have sponsored mining companies to take out licences with the International Seabed Authority (ISA), which is responsible for sustainably managing the seabed in international waters. This would allow these companies to explore the seabed and determine how viable mining is likely to be, and its potential environmental impact.

To date, ISA has approved 19 exploration contracts, 17 of which are in the CCZ. A Canadian company, The Metals Company (formerly DeepGreen Metals) has contracts with Tonga, Nauru and Kiribati.

With so little known about the biodiversity of this largely unexplored part of the ocean, it’s difficult to accurately predict how deep-sea mining will affect species here. Environmental organisations and scientists have argued for a moratorium on mining until more extensive research can be done.

Some Pacific islanders, including The Alliance of Solwara Warriors, representing indigenous communities in the Bismark and Solomon Seas of Papua New Guinea, have protested the lack of information given to local communities about the potential impact of mining. In April 2021, Pacific civil society groups wrote to the British government seeking support for a moratorium. Meanwhile, a former president of Kiribati, Anote Tong, has described deep-sea mining as “inevitable” and urged businesses to figure out how to do it safely.

But time is running out. Seven exploratory licences are due to expire in 2021, making it imperative that either a moratorium is adopted internationally, or the ISA adopts a legal framework for determining the conditions under which extractive mining can take place.

From exploration to extraction

Work towards this framework has been ongoing since 2014. Despite this, the 168 nations of the ISA assembly have yet to agree a code for regulating extractive mining contracts. The ISA’s ambition to reach an agreement in 2020 was derailed by the pandemic, and it’s unclear whether meetings will go ahead in 2021. It’s likely that exploratory contracts will expire in the meantime, increasing pressure on the ISA from mining companies and those states sponsoring them to grant exploitation licences. Exploratory licences are regulated by the ISA. Without an agreed code, extractive ones are not.

Even if a consensus were reached, enforcing environmental safeguards would be difficult. Pinpointing responsibility for the source of any pollution or environmental damage is tricky when mining takes place in such deep water. There are also few, if any, physical boundaries between one mining area and another. The effects of mining on different ecosystems and habitats might take time to manifest.

International consensus on a moratorium is unlikely too. Mining companies have ploughed a lot of money into developing technology for operating at these depths. They will want to see a return on that, and so will their investors. States which have sponsored mining contracts – including some Pacific islands – will want to reap the royalties they have been promised.

Pacific island states find themselves on the horns of a dilemma. They are among the countries most vulnerable to climate change and so support strong action. But unless alternatives are found, the developed world’s green transition will probably accelerate demand for metals resting peacefully in the deepest parts of the ocean surrounding these islands. It will be the people here who will bear the costs of deep-sea mining undertaken without sufficient caution, not the drivers of electric cars in the global north.

Sue Farran, Reader of Law, Newcastle University

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.

by DGR News Service | Jun 24, 2021 | Agriculture, Listening to the Land

This article originally appeared in Counterpunch.

By Joshua Frank

“Whiskey is for drinking, water is for fighting over.”

– Mark Twain

It doesn’t take too long once you’ve left the greater Los Angeles area, away from all the lush lawns, water features, green parkways, and manicured foliage to see that California is in the midsts of a very real, potentially deadly water crisis. Acres and acres of abandoned farms, dry lake beds, empty reservoirs—the water is simply no longer there and likely won’t ever be back.

What’s happening here in California is far more than a ‘severe drought’ as the media labels the situation. The word ‘drought’ gives the impression that this is all short-lived, an inconvenience we have to deal with for a little while. But the lack of water isn’t temporary, it’s becoming the new norm. California’s ecology as some 39.5 million residents know it is forever changing—and climate change is the culprit. At least that’s the prognosis a few well-respected climatologists have been saying for the last two decades, and their predictions have not only been accurate, but they’ve been conservative in their estimates.

UC Santa Cruz Professor Lisa Sloan co-authored a 2004 report in which she and her colleague Jacob Sewall predicted the melting of the Arctic ice shelf would cause a decrease in precipitation in California and hence a severe drought. The Arctic melting, they claimed, would warp the offshore jet stream in the Pacific Ocean. Not only have their models proved correct, Prof. Sloan told Joe Romm of ThinkProgress she believes “the actual situation in the next few decades could be even more dire” than their study suggested.

As they anticipated fifteen years ago, the jet stream has shifted drastically, essentially pushing winter storms up north and out of California and the Northwest. As a result, snowpack in the Sierra Nevadas, which feeds water to most of Southern California and the agricultural operators of the Central Valley, has all but disappeared. Winters are drier and springs are no longer wet, which means when the warm summer months roll around there’s no water to be cultivated.

The Los Angeles basin is a region that has long relied on snowmelt from mountains hundreds of miles away to feed its insatiable appetite for sprawling development, but that resource is rapidly evaporating. It is, perhaps, a just irony for the water thieves in Southern California that their wells are finally running dry. Prudence and restraint in water usage will soon be forced upon those who value the extravagant over the practical. It’s the new way across the West as climate change’s many impacts come to fruition.

Not that you’d notice much of this new reality as you travel along L.A.’s bustling boulevards. Pools in the San Fernando Valley remain full, while sun-baked Californians wash their prized vehicles in the streets and soak their green lawns in the evenings. A $500 fine can be handed out to residents who don’t abide by the outdoor watering restrictions now in place, but I’ve yet to see any water cops patrolling neighborhoods for water wasters. In fact, in Long Beach, where I live, water managers have actually admitted they aren’t planning to write any tickets. “We don’t really intend to issue any fines, at least right now,” said Matthew Veeh of the Long Beach Water Department.

Meanwhile in 2013, Gov. Jerry Brown called on all those living in the state to reduce their water use by 20 percent. That’s almost one percentage point for every California community that is at risk of running out of water by the end of the year. Gov. Brown’s efforts to conserve water have fallen on deaf ears. A report issued in July by state regulators shows a one percent increase in water consumption across the state over the past 12 months, with the biggest increase occurring in Southern California’s coastal communities.

“Not everybody in California understands how bad this drought is…and how bad it could be,” said State Water Resources Water Control Board Chairwoman Felicia Marcus when the report was first released. “There are communities in danger of running out of water all over the state.”

Perhaps there is a reason why people don’t understand how bad the water crisis really is—their daily lives have yet to be severely impacted. Unless the winter and spring bring drenching rains, California only has 12-18 months of reserves left. Even the most optimistic of forecasts show a rapid decline in water resevoirs in the state in the decades to come. To put it in perspective, California hasn’t seen this drastic of a decline in rainfall since the mid-1500s.

“This is a real emergency that requires a real emergency response,” argues Jay Famiglietti, a senior water scientist at the NASA Jet Propulsion Laboratory. “If Southern California does not step up and conserve its water, and if the drought continues on its epic course, there is nothing more that our water managers can do for us. Water availability in Southern California would be drastically reduced. With those reductions, we should expect skyrocketing water, food and energy prices, as well as the demise of agriculture.”

While it’s clear that the decline in the state’s water reserves will have a very real economic and day-to-day impact on Californians in the near future, it’s also having an inexorable and devastating effect on the environment.

The distinctive, twisted trees of Joshua Tree National Park are dying. The high desert is becoming even hotter and drier than normal, dropping nearly 2 inches from its average of just over 4.5 inches of annual rainfall. The result: younger Joshua trees, which grow at a snail’s pace of around 3 inches per year, are perishing before they reach a foot in height. Their vanishing is a strong indicator that the peculiar trees of this great Park will not be replenished once they grow old and die.

After analyzing national climate data The Desert Sun reported, “[In] places from Palm Springs to Tucson, [we] found that average monthly temperatures were 1.7 degrees Fahrenheit hotter during the past 20 years as compared to the average before 1960.”

This increase in temperatures and the decrease in yearly rainfall are transforming the landscape and vegetation of California. Sadly, Joshua trees aren’t the only native plants having a rough time surviving the changing climate. Pinyon pines, junipers, and other species are being killed by beetle infestations as winters become milder. Writes Ian James in The Desert Sun, “Researchers have confirmed that many species of trees and shrubs are gradually moving uphill in the Santa Rosa Mountains, and in Death Valley, photographs taken decades apart have captured a stunning shift as the endangered dune grass has been vanishing, leaving bare wind rippled sand dunes.”

Plants aren’t the only living organisms being dealt a losing hand. “[California’s] Native fishes and the ecosystems that support them are incredibly vulnerable to drought,” Peter Moyle, a professor at the UC Davis Center for Watershed Sciences, noted at a drought summit in Sacramento last fall. “There are currently 37 species of fish on the endangered species list in California—and there is every sign that that number will increase.”

Of those species, some eighty percent won’t survive if the trend continues. Scientists have also attributed the decline in tricolored blackbirds to the drought, which are also imperiled by development and pesticide use.

Salmon runs, however, may be taking the brunt of this human-inflicted mega-drought. According to the California Department of Fish and Wildlife, coho salmon may go extinct south of the Golden Gate straight in San Francisco if the rains don’t come quickly. As environmental group Defenders of Wildlife notes, “All of the creeks between the Golden Gate and Monterey Bay are blocked by sandbars because of lack of rain, making it impossible for salmon to get to their native streams and breed. If critically endangered salmon do not get to their range to spawn this year, they could go extinct. This possible collapse of the salmon fishery is bad news for salmon fishermen and North Coast communities. California’s salmon industry is valued at $1.4 billion in economic activity annually and about half that much in economic activity and jobs in Oregon. The industry employs tens of thousands of people from Santa Barbara to northern Oregon.”

And it’s not just the salmon fisheries that may dry up, so too may the real economic backbone of California: agriculture.

If you purchased a bundle of fresh fruits or vegetables in the U.S. recently, there’s nearly a 50 percent chance they were grown in California. And while we’ve become accustomed to paying very little for such goods compared to other Western countries, that is likely to change in the years ahead.

A study released in by the Center for Watershed Sciences at the University of California reported the ag industry in California in the first six months of 2014 lost $2.2 billion and nearly 4% of all farm jobs—some 17,000 workers. As we’re only three years into what many believe is just the beginning of the crisis, those numbers are sure to increase.

“California’s agricultural economy overall is doing remarkably well, thanks mostly to groundwater reserves,” said Jay Lund, who co-authored the study and directs the Center for Watershed Sciences. “But we expect substantial local and regional economic and employment impacts. We need to treat that groundwater well so it will be there for future droughts.”

The pumping of groundwater, which is being treated as an endless and bountiful resource, may be making up for recent water loss, but for how long remains to be seen. Until 2014, when the state passed The Sustainable Groundwater Management Act, California was the only state in the country that did not have a framework for groundwater management. For decades farmers sucked the desert’s groundwater supply dry, so much so, that the entire sections of California ag country sunk by 60 centimeters.

“We have to do a better job of managing groundwater basins to secure the future of agriculture in California,” said Karen Ross, secretary of the California Department of Food and Agriculture. “That’s why we’ve developed the California Water Action Plan and a proposal for local, sustainable groundwater management.”

Nonetheless, without significant rainfall, groundwater will not be replenished, the state’s agribusiness and the nation’s consumers will most certainly be hit with the consequences. Rigid conservation and appropriate resource management may act as a bandaid for California’s imminent water crisis, but if climate models remain accurate, the melting of Arctic ice will continue to have a severe impact on the Pacific jet stream, weakening winter storm activity across the state.

It’s a precarious situation, not only for millions of people and the nation’s largest state economy—but it could be the death knell for much of California’s remaining wildlife and iconic beauty as well.

JOSHUA FRANK is managing editor of CounterPunch. His most recent book, co-authored with Jeffrey St. Clair, is Big Heat: Earth on the Brink. He can be reached at joshua@counterpunch.org. You can troll him on Twitter @joshua__frank.

![Tribe, Ranchers Say Proposed Lithium Mine in Wikieup Will ‘Ruin’ Their Water [Dispatches from Thacker Pass]](https://dgrnewsservice.org/wp-content/uploads/sites/18/2021/06/dsc_8868.jpg)

by DGR News Service | Jun 22, 2021 | Biodiversity & Habitat Destruction, Colonialism & Conquest, Indigenous Autonomy, Mining & Drilling, Movement Building & Support, Repression at Home, Toxification

This article originally appeared on the Protect Thacker Pass Blog.

Featured image: Photo of Damon Clarke, chairman of the Hualapai Tribe by Josh Kelety

Thacker Pass gets a mention in this article in the Phoenix New Times about another proposed lithium mine in Arizona, one that would use the same sulfuric acid leaching process that the Thacker Pass lithium mine would use. It’s also yet another mine threatening the water and land of indigenous people.

“The brewing tension surrounding the project in Wikieup represents a broader fight over lithium mining that is taking place in other states. Increasing use of electric cars and renewable energy has caused demand for lithium to soar, with projections for even more needed in the near future. But some observers are raising red flags, like in Wikieup, about the potential harmful environmental impacts of lithium mines.”

In this case the mining company is Hawkstone Mining, another foreign mining company (Australian, like Jindalee, the mining company that wants to mine lithium just across the OR border from Thacker Pass).

As members of the Hualapai Tribe noted, the mining would disturb their cultural sites (just like the Thacker Pass mine would disturb the cultural sites of the Paiute Shoshone people), and could use up or contaminate ground water in a state in the middle of extraordinary drought.

“There is no water in the state of Arizona. Everyone is fighting for water. Here, in this area, it’s arid and there’s not a lot of water. Whatever water there is here has already been taken by farming and ranching. To allow a big industry to come in that’s going to use tons of water and ruin our water system … then it’s a big problem. This place can’t support something that uses a lot of water, whether it’s lithium or not. We’re all in support of changing our consumption of fossil fuels. But at the cost of the environment just to get that for more cellphones and whatever else, it’s a problem.”

— Hualapai Tribe Councilmember Richard Powskey

Peehee mm’huh / Thacker Pass is a special, unique and wonderful place. AND our effort at Thacker Pass is representative of a growing struggle throughout the American West as mining companies ramp up to meet projected lithium demand for EV batteries and energy storage and an ever-increasing number of devices.

As we said when we began this fight: this is just the beginning. We take a stand at Peehee mm’huh for all the land and water that may otherwise be stolen for lithium for cars and gadgets and technology that we do not “need” to live well on this beautiful Earth.

Join us to #ProtectThackerPass and all the other lands under threat from mining.

For more on the Protect Thacker Pass campaign

#ProtectThackerPass #NativeLivesMatter #NativeLandsMatter

by DGR News Service | Jun 20, 2021 | Biodiversity & Habitat Destruction, Colonialism & Conquest, Indigenous Autonomy, Mining & Drilling, NEWS, Repression at Home, Toxification

- Vale, the Brazilian mining company responsible for two deadly dam collapses since 2015, has another dam that’s at “imminent risk of rupture,” a government audit warns.

- The Xingu dam at Vale’s Alegria mine in Mariana municipality, Minas Gerais state, has been retired since 1998, but excess water in the mining waste that it’s holding back threatens to liquefy the embankment and spark a potentially disastrous collapse.

- Liquefaction also caused the collapse of a Vale tailings dam in 2019 in Brumadinho municipality, also in Minas Gerais, that killed nearly 300 people; the 2015 collapse of another Vale dam, in Mariana in 2015, caused extensive pollution and is considered Brazil’s worst environmental disaster to date.

- Vale has denied the risk of a collapse at the Xingu dam and says it continues to monitor the structure ahead of its decommissioning; regulators, however, say the company still hasn’t carried out requested measures to improve the structure’s safety, and have ordered an evacuation of the immediate vicinity.

This article originally appeared in Mongabay.

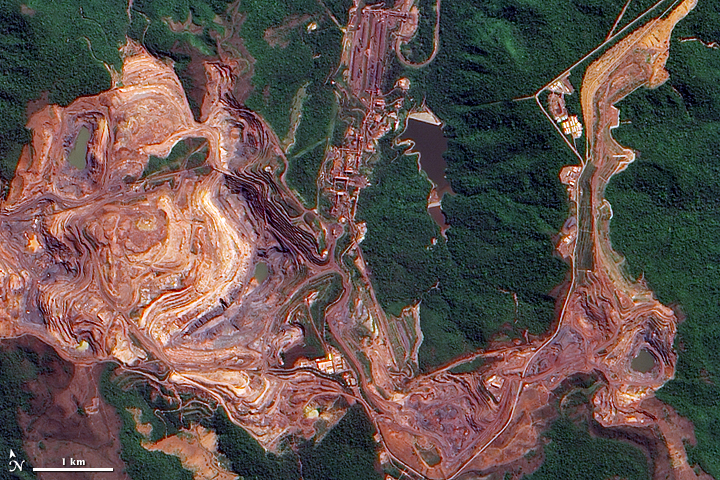

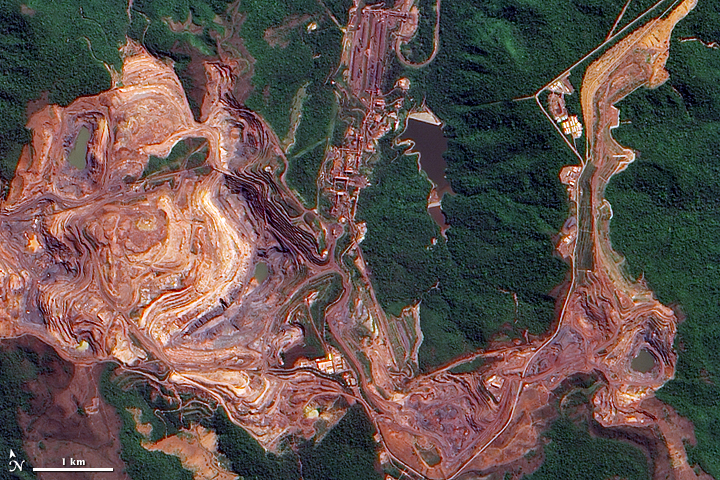

Featured image: Vale’s Xingu mining complex in Mariana. Image by Google.

by Juliana Ennes

A dam holding back mining waste from Brazilian miner Vale is at risk of collapsing, a government audit says. The same company was responsible for two tailings dam collapses since 2015 that unleashed millions of gallons of toxic sludge and killed hundreds of people in Brazil’s southeastern state of Minas Gerais.

The retired Xingu dam at Vale’s Alegria iron ore mine in Mariana — the same municipality where a Vale tailings dam collapsed in November 2015 in what’s considered Brazil’s worst environmental disaster to date — is at “serious and imminent risk of rupture by liquefaction,” according to an audit report from the Minas Gerais state labor department (SRT), cited by government news agency Agência Brasil. The SRT did not immediately reply to Mongabay’s emailed requests for comment; it also did not answer any phone calls.

In the May 20 audit report, only released last week, the SRT said the Xingu dam “does not present stability conditions.” “It is, therefore, an extremely serious situation that puts at risk workers who perform activities, access or remain on the crest, on the downstream slopes, in the flood area and in the area on the tailings upstream of the dam,” the document says.

In a statement, Vale denied the imminent risk, saying the dam “is monitored and inspected daily.” It said the structure’s conditions and safety level remain unchanged, rated level 2 on a three-point scale.

The 2015 collapse of the Fundão tailings dam belonging to Samarco, a joint venture between Vale and Anglo-Australian miner BHP Billiton, killed 19 people in the village of Bento Rodrigues, burying them in toxic mud, and flushing mining waste into rivers that affected 39 municipalities across two states. The mining waste eventually flowed more than 650 kilometers (400 miles) from its source to the Atlantic Ocean.

The district prosecutor’s office in Mariana told Mongabay that the Minas Gerais state prosecutor-general has requested the National Mining Agency (ANM) to assess the real risk of the dam rupture. “Any irregularity in the change in the classification of the structure will be evaluated after the inspection carried out by the ANM and, if necessary, with subsequent investigations,” the district prosecutor’s office said.

The ANM rated the Xingu dam’s safety at level 2 in a September 2020 assessment, after requesting Vale to improve the structure. Vale has fulfilled part of the request, but has sought a deadline extension for other repair works, without major changes in the structure, according to the ANM’s website.

In its most recent inspection, on May 5, ANM identified structural problems where no corrective measures had been implemented, according to its website. By then, the ANM considered the potential environmental impact “relevant” and the socioeconomic impact “medium,” given the concentration of residential, farming and industrial facilities located downstream of the dam.

Vale ceased dumping mining waste in the Xingu dam in 1998, but keeps workers on site to monitor the dam’s stability until it’s fully decommissioned. The decommissioning plans is in place but hasn’t been carried out yet, according to Ronilton Condessa, director of the Mariana mining workers’ union, Metabase. No timeline has been given for the decommissioning; a similar structure, the Doutor dam at Vale’s Timbopeba mine in neighboring Ouro Preto municipality, will take up to nine years.

Last week, Vale announced the suspension of train operations to the Mariana complex where its Alegria mine is located, after an evacuation order from labor auditors. The area in the immediate vicinity of the mine, known as the self-rescue zone, remains evacuated. Work at both the Timbopeba and Alegria mines has been halted.

Condessa said that because the Xingu dam is located inside the mining complex, workers continue to pass by it daily on their way to other mines that are still active.

Vale has scheduled a meeting with workers from the dam for June 16 to explain the current situation, according to Condessa. “The evacuation orders look like a preventive measure, but we still need to see a technical study in order to properly evaluate the risk,” he told Mongabay in a phone interview.

The Minas Gerais state civil defense agency said the evacuation of the self-rescue zone was ordered on a “preventive basis to protect the lives of people living downstream of the dam.”

“In collaboration with the SRT, Vale is taking measures to continue to guarantee the safety of workers, in order to resume activities,” Vale said in a June 4 statement.

A two-and-a-half-hour drive west of the Alegria mine in Mariana is the municipality of Brumadinho. This was the site in 2019 of Brazil’s deadliest mining disaster, when a tailings dam at Vale’s Córrego do Feijão iron ore mine collapsed, killing nearly 300 people. The cause of the dam’s failure was attributed to a process known as liquefaction, in which excess water weakens the dam’s embankment. This is the same risk recently identified at the Xingu dam at Vale’s Alegria mine.

by DGR News Service | Jun 19, 2021 | Biodiversity & Habitat Destruction, Lobbying, Mining & Drilling, Movement Building & Support, Repression at Home

Brazil’s Movimento dos Atingidos por Barragens has been fighting for decades against the privatization of water and for popular control over natural resources.

This article originally appeared in Roarmag.

Featured image: Vale open pit iron ore mine, Carajas, Para, 2009

By Caitlin Schroering

Todos somos atingidos

(“We are all affected”)

— Common MAB saying

A person can go a few weeks without food, years without proper shelter, but only a few days without water. Water is fundamental, yet we often forget how much we rely on it. Only 37 percent of the world’s rivers remain free-flowing and numerous hydro dams have destroyed freshwater systems on every continent, threatening food security for millions of people and contributing to the decimation of freshwater non-human life.

Dams and dam failures have catastrophic socio-environmental consequences. In the 20th century alone, large dam projects displaced 40 to 80 million people globally. At the same time, the communities most impacted by dams have been typically excluded from the political decision-making processes affecting their lives.

In Brazil there is an extensive network of mining companies, electric companies and other corporate powers that construct, own and operate dams throughout the country. But for the communities directly affected by hydro dam projects, water and energy are not commodities. Brazil’s Movement of People Affected by Dams (Movimento dos Atingidos por Barragens, or MAB — pronounced “mah-bee”) fights against the displacement and privatization of water, rivers and other natural resources in the belief that everyday people should have sovereignty and control over their own resources.

MAB is a member of La Via Campesina, a transnational social movement representing 300 million people across five continents with over 150 member organizations committed to food sovereignty and climate justice. MAB also works with social movements across Brazil, including the more widely-known Landless Workers Movement (MST), unions and human rights organizations. These alliances speak to the importance of peasant movements and Global South movements in constructing globalizations from below.

MAB focuses its fights on six interconnected areas: human rights, energy, water, dams, the Amazon and international solidarity. The movement organizes for tangible policy and system-level changes and actively creates an alternative to capitalist globalization.

DISASTER CAPITALISM

Just over two years ago, on January 25, 2019, the worst environmental crime in Brazil’s history resulted in the loss of 272 lives. In Córrego do Feijão in Brumadinho, in the state of Minas Gerais, a dam owned by the transnational mining company Vale collapsed. Originally a state-owned company, Vale was privatized in 1997 and since then has made untold billions of dollars mining iron ore and other minerals.

Brazil is the world’s second-largest producer of mineral ores and in 2018 iron ore accounted for 20 percent of all exports from Brazil to the United States. More than 45 percent of Vale’s shareholders are international, including some of the world’s largest investment management companies based in the US such as BlackRock and Capital Group.

The logic of profit has dispossessed people of their sovereignty, their wealth and their water, the very essence of life. The massive dams Vale uses in its mining operations privatize and pollute water used by thousands of people.

When you fly over the state of Minas Gerais, you can see the iron mines as large gaping holes in the ground. Vale and its subsidiaries own and control 175 dams in Brazil, of which 129 are iron ore dams and Minas Gerais accounts for the vast majority of these. Minas Gerais is a region where thousands of people depend upon the water for their livelihood and survival, but the mining leaves the water contaminated. Agriculture and fishing are disrupted or halted, and residents struggle to live without access to potable water.

Exacerbating the problems associated with the privatization and contamination of water for residents, local economy and ecosystems, the dams themselves are vulnerable: the types of dams Vale uses are relatively cheap to build, but also present higher security risks because of their poor structure. When the Brumadinho iron ore mine collapsed, it released a mudflow that swept through a worker cafeteria at lunchtime before wiping out homes, farms and infrastructure. The disaster killed 272 people and an additional 11 people were never found. What made it a crime was that Vale knew something like this could happen. In an earlier assessment, Vale had classified the dam as “two times more likely to fail than the maximum level of risk tolerated under internal guidelines.”

The Associação Estadual de Defesa Ambiental e Social (State Association of Environmental and Social Defense) conducted an assessment and released a report in collaboration with more than 7,000 residents in the regions impacted by the dam collapse. This report shows that depending on the town — the effects of the collapse vary from those communities buried in mud, to those impacted further downstream — 55 to 65 percent of people currently lack employment due to the dam disaster.

Brumadinho is considered one of the worst socio-environmental crimes in the history of Brazil, but it is far from the only one. Five years ago, a dam collapsed in Mariana, killing 20 people; the impacted communities still suffer the effects and are without reparations. On the second anniversary of the Brumadinho collapse, on January 24, 2021, another dam collapsed in Santa Catarina. On March 25, 2021, a dam in Maranhão state, owned by a subsidiary of the Canadian company Equinox Gold, collapsed, polluting the water reservoir of the city of Godofredo Viana, leaving 4,000 people without potable water.

On January 22, 2021, MAB held a virtual international press conference to commemorate two years since the Brumadinho collapse. Jôelisia Feitosa, an atingida (an “affected person”) from Juatuba, one of the communities affected by the dam collapse, described the fallout. People are suffering from skin diseases due to the contaminated water; small farmers cannot continue with their livelihood; people who relied on fishing can no longer do so. As a result, many people have been forced to leave. The lack of potable water has created an emergency. Feitosa said that presently, there are “not conditions for surviving here” anymore. The after-effects of the collapse, compounded by the pandemic, continue to take lives.

There are more than 100,000 atingidos in the region, but people do not know what is going to happen or when emergency aid will come. Further, government negotiations with Vale for “reparations” were conducted without the participation of atingidos. On February 4, 2021, the Brazilian government and Vale reached an accord. Nearly US$7 billion was awarded to the state of Minas Gerais, making it the largest settlement in Brazil’s history, along with murder charges for company officials.

To MAB, however, the accord is illegitimate. It was made under false pretenses, the affected population was not included in the process, and the money, which is not even going to those who are most impacted, does not begin to cover the irreparable and continuing damages. As José Geraldo Martins, a member of the MAB state coordination, said: “[Vale’s] crime destroyed ways of life, dreams, personal projects and the possibility of a future as planned. This leads to people becoming ill, emotionally, mentally, and physically. It aggravates existing health problems and creates new ones.”

As Feitosa put it: “Vale is manipulating the government, manipulating justice.” The accord was reached without the full participation of atingidos, and to make matters worse, Vale decided who qualifies as an atingido based on whether or not people have formal titles to ancestral lands. Vale’s actions create a dangerous precedent that allows corporations to extract, exploit and take human life with impunity. Nearly 300 people died from the 2019 dam collapse, and since then almost 400,000 people have died in Brazil from COVID-19. Yet, during this time, Vale has made a record profit. Neither the dam collapse nor the pandemic has stopped production or profits, even as workers are dying.

FIGHTING BACK: MAB’S STRUGGLE FOR WATER AND LIFE

MAB is committed to continued resistance and will bring the case to the Supreme Court. MAB organizes marches and direct actions and also partners with other movements in activities all across Brazil. They have recently occupied highways and blocked the entrance and exit of trucks to Vale’s facilities. MAB also uses powerful, embodied art and theater called mística that tells a real story and asks participants to put themselves into mindset that “we are all affected.”

MAB emphasizes popular education to understand how historical processes inform present-day struggles. Drawing heavily on Paulo Freire’s Pedagogy of the Oppressed, they focus on collaborative learning and literacy by making use, for example, of small break-out groups where people take turns reading and discussing short passages. In these projects, there is an intentional effort to fight against interlocking systems of oppression: classism, racism, heterosexism and patriarchy, which are viewed as interlinked with capitalism at the root.

MAB also has a skilled communication team that makes use of online media, including holding frequent talks and panels broadcast via Facebook Live. A recent MAP pamphlet entitled, “Our fight is for life, Enough with Impunity!” details four women important to MAB’s struggle: Dilma, Nicinha, Berta and Marielle. Dilma and Nichina are two women atingidas who were murdered in their fights against dam projects in their communities. Berta was a Honduran environmentalist who also engaged in dam struggles and was murdered. Marielle was a Black, lesbian, socialist city-councilwoman (with Brazil’s Socialism and Liberty Party) in Rio who was murdered in 2018.

For MAB, the struggles of those who have died in their fight for a better world serve as seeds of resistance, a theme further explored in their film “Women Embroidering Resistance.”

For the past two years, MAB has organized events to commemorate the anniversary of the crime committed by Vale in Brumadinho. In 2020, MAB organized a five-day march and international seminar, beginning in Belo Horizonte, Minas Gerais’ state capital, and ending in Córrego do Feijão with a memorial service. Hundreds of people from around Brazil as well as allies from 17 countries marched through Belo Horizonte, chanting, “Vale killed the people, killed the river, killed the fish!”

Famed liberation theologian Leonardo Boff is a supporter of MAB and spoke at the seminar, decrying that letting people starve is a sin and asserting that “everyone has the right to land; everyone has the right to education; everyone has the right to culture; we all need security and have the right to housing—these are common and basic rights.” He went on: “We don’t get this world by voting — we need participatory democracy.”

MAB commemorated the second anniversary of Brumadinho this past January with various symbolic actions. In one such event, people tossed 11 roses into the water to honor the 11 people who have still not been found, with additional petals to honor the river that has been killed by the mining company. They also organized various virtual actions since the pandemic precluded an in-person convergence like the one held the year before.

JUSTICE THROUGH STRUGGLE AND ORGANIZATION

Less than a month after commemorating Brumadinho in 2020, COVID-19 exploded and the world went into lockdown. Brazil is now one of the hardest-hit countries with the actions and inactions of right-wing president Jair Bolsonaro — from calling COVID-19 a “little flu” to encouraging people to take hydroxychloroquine as a remedy, to defunding the public health system, and cutting back social services — leading to a dire situation.

In April, Brazil recorded over 4,000 COVID-19 deaths in 24 hours, with a death toll second only to the United States. On May 30, the official death toll from COVID-19 was 461,931. Brazil will not soon realize vaccine distribution to the entire population, and people continue to die from lack of oxygen in some regions, prompting an investigation of Bolsonaro and the health minister for mismanagement.

On May 29, 2021, MAB participated in protests with other social movements, unions and the population in general that spanned across 213 cities in Brazil (and 14 cities around the world). The protesters called for Bolsonaro’s impeachment, demanded vaccines and emergency aid for all, and denounced cuts to public health care and education as well as efforts to privatize public services.

In the past five years, the number of Brazilians experiencing hunger has grown to nearly 37 percent. The COVID-19 crisis has only worsened this reality. In August 2020, Bolsonaro vetoed a bill that would have granted emergency assistance to family farmers.

But Brazil’s story is one of resistance, resilience and hope. Efforts bringing together many social movements, unions and other popular organizations have mounted critical mutual aid efforts. MAB is a leader in these efforts, putting together baskets with essential food, hand sanitizer and other essential goods for families in need. The pandemic presents significant challenges, but MAB has continued to resist Bolsonaro’s policies. For example, they are fighting against the defunding of the national public health care system and continuing to organize in communities impacted by dam projects or threatened by new ones.

The fight for the right to water and against the socio-environmental impacts of dams is global. MAB’s struggle is one of resistance against the capitalist system for a world where the rights of people come ahead of profit. As MAB has said: “In 2020, Brazil did not sow rights; on the contrary, the country took lives, especially the lives of women, Black and poor people, all with a lot of violence and impunity.”

MAB’s struggle extends beyond the fight against water privatization. It is part of a global effort to regain the commons of water and fight against the commodification and privatization of life. MAB’s insistence that all forms of oppression are interconnected is also a statement of hope and a catalyst for envisioning a different world. Imagining new possibilities is a prerequisite for creating them.

This year, MAB celebrates 30 years of fighting to guarantee rights and their message is that the only way is to fight and organize: “Justice only with struggle and organization.” In doing so, they are sending a strong message to Vale: they cannot commit a crime like Brumadinho again and profit will not be valued over life.

Caitlin Schroering holds a PhD in Sociology from the University of Pittsburgh. She has 16 years of experience in community, political, environmental and labor organizing.

![]()

![Tribe, Ranchers Say Proposed Lithium Mine in Wikieup Will ‘Ruin’ Their Water [Dispatches from Thacker Pass]](https://dgrnewsservice.org/wp-content/uploads/sites/18/2021/06/dsc_8868.jpg)