by DGR News Service | Jun 28, 2019 | Agriculture

By Steven Earl Salmony, Ph.D., M.P.A / Image: CC BY 3.0

One voice from the wilderness is too weak to be listened to. My voice, for example, is not clear enough, strong enough, loud enough or adequately established so as to be heard. How can any person in a position of influence among our most wealthy and powerful leaders possibly be expected to receive a ‘best available science message’ until we and others who are similarly situated speak out, as if with one voice, about what could be somehow real, according to the best available science and ‘lights’ we possess?

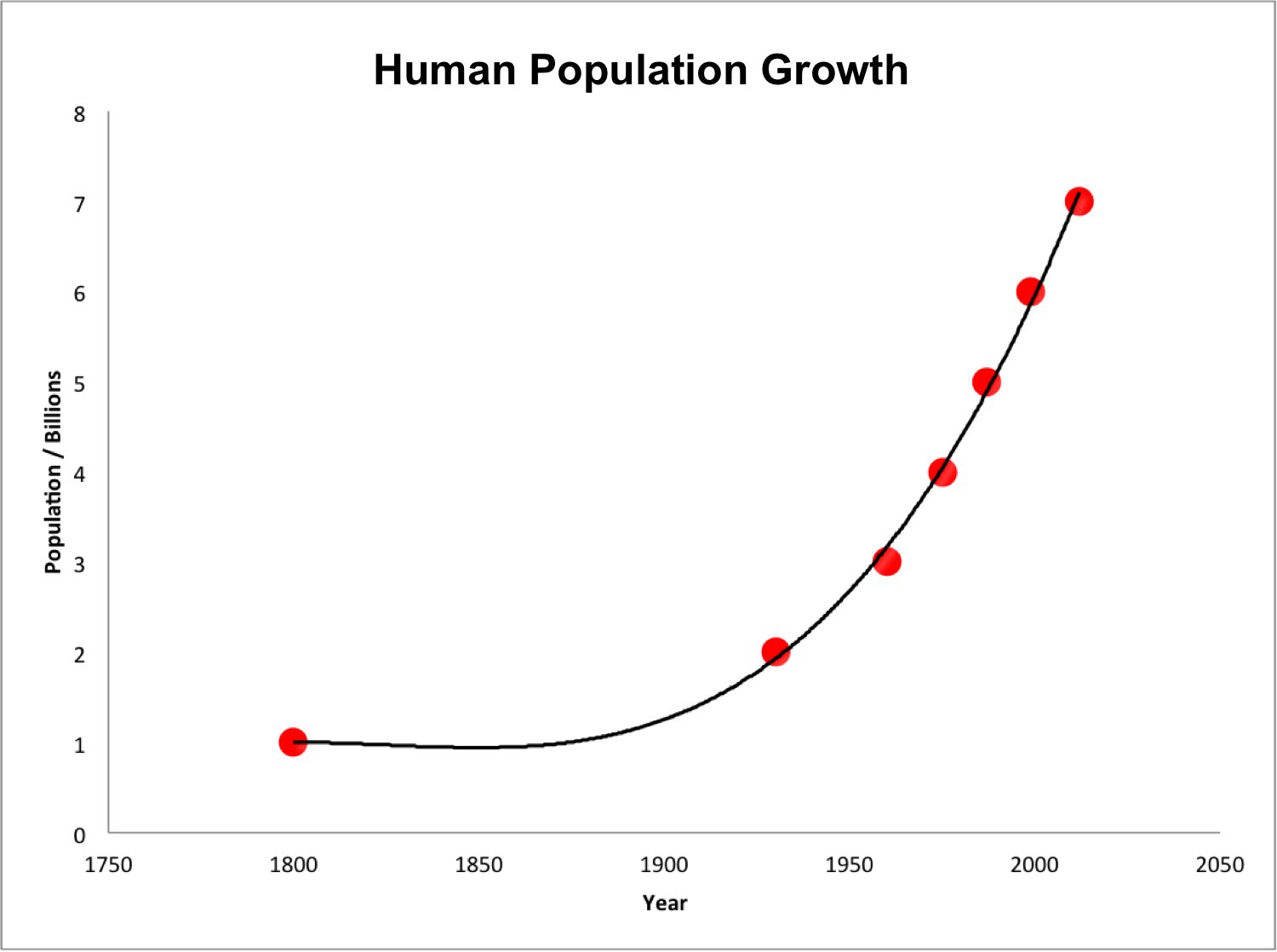

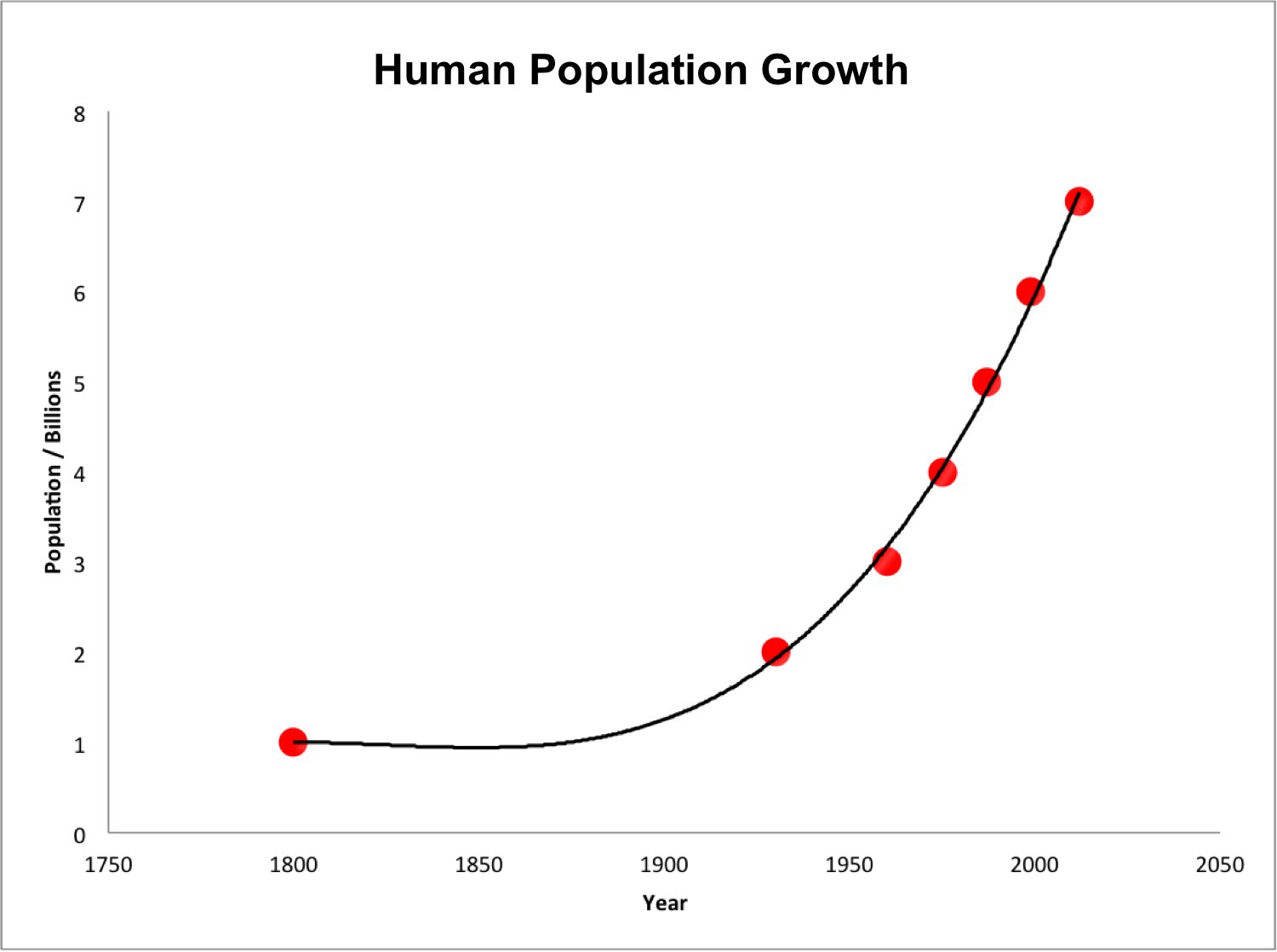

Declining fertility rates virtually everywhere on Earth need not blind us to the undeniable, ongoing annual increases of absolute global human population numbers. Human numbers have exploded by more than 5 billion on earth in the past three score and ten years. This population growth ‘trajectory’ is patently unsustainable on a planet with the size, finite resources and frangible ecology of Earth. Please consider how the growth of human numbers worldwide is caused by the spectacular production and distribution of food for human consumption. With each passing year more people are being fed and more people are going hungry.

For years we have been encouraged to ‘think globally’. Let us hope that it is not too late to begin ‘acting globally’. There is no time to waste because untethered overproduction, overconsumption and overpopulation activities of the human species are on the verge of causing a global ecological wreckage of the planet we inhabit by turning Earth’s land surface into mountains of human detritus and its seas into sewers.

As things stand, the leading self-righteous elders in the world, on our watch, are charting a course to the future that will wreak havoc on what is surely sacred and normalize what is plainly profane…come what may. And these self-proclaimed ‘masters of the universe’ erroneously believe that they can have some faraway island or mega-yacht to which an escape from the global ecological wreckage would be possible. More evidence of immaculate hubris, I suppose.

Those few with power would like the status quo to remain as is; whereas, the many, too many, without power want necessary change and a ‘course correction’ while a ‘window of opportunity’ remains open. Note to us all: the window is closing steadily in our time. When unbridled production, consumption and propagation activities of the human species are occurring synergistically, expanding rampantly and effectively overspreading earth, perhaps this moment in space-time is an occasion to do something that is different and somehow right… for a change.

No one knows what is possible once we begin somehow to do things differently from the ways that we are doing things now here on our planet. At the moment we know that silence has overcome science; that greed has vanquished fairness and equity; that ignorance and stupidity have almost obliterated common sense and reason; that hubris has virtually annihilated humanness. Like it or not, ready or not, we are presented with enormous challenges.

Let us hope that our most able responses to the human-induced and -driven existential ecological threats looming ominously before humanity do not come too late to make a difference that makes a difference. There is much to do. Human limits, global planetary limitations and time constraints are the factors to which we are called upon to respond ably with all deliberate speed.

If only the world worked the way we want it to! That all-too-human creatures of Earth were actually self-proclaimed ‘masters of the universe’ in more ways than ‘name only’. By evading extant scientific knowledge about our distinctly human creatureliness and the biophysical limitations of the planet we inhabit; by widely sharing and consensually validating utterly false, hubristic thinking regarding our seemingly god-like super-human capabilities and Earth as a maternal presence eternally giving; by denying that earth is relatively small and finite with a frangible environment, it may be that the human community is not able to evade the consequences of our patently unsustainable behavior. Can we rise above our apparent incapacity to respond ably or not? Can we do so in a short time-frame so we avoid insurmountable ‘doomsday scenarios’?

Note the exquisite talents demonstrated by the savants among us or the teachers, poets, artists from whom there emanates universally shared, humane values, principles and practices for living or the leaders who have not sold out their souls for the poisoned fruits of power, gluttony, greed, wrath, pride, envy and effortless ease. The global challenges presented to our generation of elders are likely different from the threats to human well-being that had to be confronted by our ancestors. But that does not mean, even for a moment, that their challenges were either more or less difficult from the ones we face.

If our ancestors had not acknowledged, addressed and overcome the challenges before them, I dare say that we would not be here now. It does not appear that our generation of elders has so much as begun to struggle in a meaningful way with the global challenges before us. We collectively have been running away from our responsibilities and duties to the family of humanity and Earth’s well-being in general.

Our children and their children after them will say that we have failed them. Their true statement, perhaps spoken someday soon as a refrain, is not acceptable and cannot become our enduring legacy to life on this planet and to the planet, itself. We cannot luxuriate in our willful ignorance and self-serving hysterical blindness any longer.

The moment to step up, take hold, and move forward courageously is at hand. The time has come to accept the challenges already dimly visible in the offing.

Let us speak out as if we are a million voices because so many of us remaining electively mute make us complicit in the destruction of Earth and life as we know it. Are better, more responsible courses of action available to us? If so, other ways of going forward need to be discovered, discussed and implemented, fast.

—

Steven Earl Salmony, Ph.D., M.P.A. established The AWAREness Campaign on The Human Population in 2001. He lives in Fearrington Village, NC, USA and can be contacted at sesalmony@aol.com.

by DGR News Service | Jun 18, 2019 | Agriculture, Biodiversity & Habitat Destruction, The Solution: Resistance, Toxification

By Will Falk and Sean Butler

Photo: 2009 algae bloom in western Lake Erie. Photo by Tom Archer.

It should be clear to anyone following the events surrounding attempts by the citizens of Toledo, OH, with help from nonprofit law firm the Community Environmental Legal Defense Fund (CELDF), to protect Lake Erie with the Lake Erie Bill of Rights, that the American legal system and all levels of government in their current form exist to protect corporations’ ability to destroy nature in the name of profit and protect those corporations from outraged citizens injured by corporate activities.

In the scorching summer heat of August 2014, nearly half a million people in Toledo, OH were told not to use tap water for drinking, cooking, or bathing for three days because a harmful algae bloom poisoned Lake Erie. Harmful algae blooms on Lake Erie have become a regular phenomenon. They produce microcystin, a dangerous toxin. Microcystin “causes diarrhea, vomiting, and liver-functioning problems, and readily kills dogs and other small animals that drink contaminated water.” The Ohio Environmental Protection Agency reports that mere skin contact with microcystin-laden harmful algae blooms can cause “numbness, and dizziness, nausea…skin irritation or rashes.” Scientists have also discovered that harmful algae blooms produce a neurotoxin, BMAA, that causes neurodegenerative illness, and is associated with an increased risk of ALS, and possibly even Alzheimer’s and Parkinson’s. In 2018, a federal judge found that the principal causes of Lake Erie’s perennial harmful algae blooms are “phosphorus runoff from fertilizer, farmland manure, and, to a lesser extent, industrial sources and sewage treatment plant discharges.”

The Environmental Working Group and Environmental Law and Policy Center report that, not surprisingly, between 2005 and 2018 the number of factory farms in the Maumee river watershed – a river that flows into Lake Erie and boasts the largest drainage area of any Great Lakes river

“exploded from 545 to 775, a 42 percent increase. The number of animals in the watershed more than doubled, from 9 million to 20.4 million. The amount of manure produced and applied to farmland in the watershed swelled from 3.9 million tons each year to 5.5 million tons.”

The groups also state that “[t]he amount of phosphorus added to the watershed from manure increased by a staggering 67 percent between 2005 and 2018.” And, “69 percent of all the phosphorus added to the watershed each year comes from factory farms in Ohio.”

Many Americans believe regulatory laws like the Clean Water Act and regulatory agencies like the United States Environmental Protection Agency (EPA) exist to protect against phenomena like harmful algae blooms. But, Senior US District Court Judge James G. Carr recently described how regulatory laws and agencies have failed to protect Lake Erie. In a 2018 decision in a case brought by the Environmental Law and Policy Center under the Clean Water Act for the failures of the US and Ohio EPAs, Carr described, “Ohio’s long-standing, persistent reluctance and, on occasion, refusal, to comply with the [Clean Water Act].” He also wrote:

“As a result of the State’s inattention to the need, too long manifest, to take effective steps to ensure that Lake Erie (the Lake) will dependably provide clean, healthful water, the risk remains that sometime in the future, upwards of 500,000 Northwest Ohio residents will again, as they did in August 2014, be deprived of clean, safe water for drinking, bathing, and other normal and necessary uses.”

Despite Carr explaining that he “appreciate[s] plaintiffs’ frustration with Ohio’s possible continuation of its inaction,” he ruled that he could not expedite Ohio’s compliance with the Clean Water Act because he could not determine that Ohio had “clearly and unambiguously” abandoned its obligations under the Clean Water Act.

In response to the regulatory framework’s failure to stop harmful algae blooms, on Tuesday, February 26, 2019, citizens in Toledo, OH voted to protect Lake Erie with the Lake Erie Bill of Rights (“LEBOR” or “the Bill”). The Bill “establishes irrevocable rights for the Lake Erie Ecosystem to exist, flourish, and naturally evolve, a right to a healthy environment for the residents of Toledo” and “elevates the rights of the community and its natural environment over powers claimed by certain corporations.”

Toledoans for Safe Water (TSW) is the grassroots coalition of local Toledo citizens who ushered the Bill through Ohio’s constitutional citizen initiative process. Ohio’s citizen initiative process allows citizens to draft and propose laws and to place those laws on a ballot so citizens can directly vote on the law’s enactment. Typically, laws are drafted, proposed, and voted on solely by legislators. Initiative processes like Ohio’s are some of the only avenues American citizens have for directly proposing and enacting laws and providing a direct check and balance on an “out of touch” or corrupt legislature. It is important to understand, however, that, even with citizen initiative processes, it is incredibly difficult to not only democratically enact laws that would actually protect the natural world, but it is incredibly difficult to even place rights of nature laws on the ballot in the first place.

Toledoans for Safe Water’s experience is enlightening. Formed after the harmful algae bloom of August 2014, TSW worked tirelessly to pass an initiative protecting their water source including overcoming efforts by the Lucas County Board of Elections and BP North America to keep such an initiative off the ballot. First, TSW had to gather 5,244 signatures to place LEBOR on the ballot. They far exceeded that total by gathering approximately 10,500 signatures. Despite gathering much more than the necessary signatures, the Lucas County Board of Elections voted against putting the initiative on the November 2018 ballot.

Toledoans for Safe Water members sought an order from the Ohio Supreme Court to put the measure on the ballot, but the Court denied the request in September 2018. Fortunately, in October 2018, in another case involving a different charter initiative, the Ohio Supreme Court ruled that city councils may force county boards of election to place charter amendment initiatives on the ballot. This ruling expressly overruled precedent previously relied on to prevent Toledo citizens from voting on LEBOR. Armed with this new ruling, TSW successfully asked the Toledo City Council to put LEBOR on the ballot. However, in December 2018, a Toledo citizen sought a writ of prohibition from the Ohio Supreme Court to block LEBOR. TSW found themselves in front of the Ohio Supreme Court once again. This time TSW won.

After ensuring LEBOR made it to the ballot, Toledoans for Safe Water had to convince enough voters to vote for the Bill before it could be enacted. In the weeks leading up to the election, BP North America wired $302,000 to the Toledo Coalition for Jobs and Growth, the primary group opposing LEBOR. In the end, TSW spent $7,762 in support of LEBOR, while Toledo Coalition for Jobs and Growth, with the massive donation from BP North America, spent $313, 205 to stop LEBOR. Despite this disparity, LEBOR passed with 61 percent of the 15,000 Toledoans who voted.

But, mere hours after the City of Toledo certified LEBOR’s election results, Drewes Farms Partnership sued the City seeking an injunction against enforcing LEBOR and a court ruling that LEBOR is unconstitutional. Several Toledo city-council members spoke out against the enactment of LEBOR before the election, and it appears that the City will not enforce LEBOR. Yes, you read that correctly: After LEBOR won with 61% of the vote (nearly two-thirds of those who voted), the City of Toledo agreed to an injunction prohibiting them from enforcing the law.

In response to such bald face tactics, we must ask, if a local city government agrees not to enforce the will of its citizens, then what really is left of the notion of a government for and by the people? And the inevitable answer must be, nothing. Indeed, as environmental author Derrick Jensen explains in his book Endgame:

“Surely by now there can be few here who still believe the purpose of government is to protect us from the destructive activities of corporations. At last most of us must understand that the opposite is true: that the primary purpose of government is to protect those who run the economy from the outrage of injured citizens.”

Jensen’s conclusion eerily reflects the very plain statement by Attorney General Richard Olney, who served under President Grover Cleveland in 1894 about the newly-formed Interstate Commerce Commission. The ICC was the very first federal regulatory agency, created to ‘regulate’ the railroad industry, but as Olney (a former railroad attorney, himself) said:

“The Commission…is, or can be, made of great use to the railroads. It satisfies the popular clamor for a government supervision of railroads, at the same time that that supervision is almost entirely nominal. Further, the older such a commission gets to be, the more inclined it will be found to take the business and railroad view of things.”

Nearly 200 years later, Jensen’s observation reflects the reality that not only does our regulatory system not protect the interests of the people of this country; it was never intended to. It was created to protect industry.

And so the parade of horribles that Toledoans for Safe Water have encountered should come as no surprise. A little over two months after the lawsuit was filed by the agriculture industry to strike down LEBOR, the State of Ohio requested, and was granted, the right to intervene to argue with Drewes Farms Partnership that LEBOR should be invalidated. TSW also tried to intervene on behalf of Lake Erie, exercising their new rights under LEBOR and arguing that the City is not an adequate representative of LEBOR. The City neither opposed TSW’s intervention in the case, nor denied that it would be an inadequate representative of LEBOR. Regardless, on Tuesday, May 7, Judge Jack Zouhary, a U.S. District Judge in the Northern District of Ohio, Western Division denied Toledoans for Safe Water’s intervention. Lake Erie and TSW asked the Sixth Circuit Court of Appeals to stay (legalese for postpone) the case while they appealed Zouhary’s denial of their intervention. But, the Sixth Circuit refused to stay the case.

Because Zouhary has denied Toledoans for Safe Water’s intervention and the Sixth Circuit did not grant Lake Erie’s and TSW’s request to stay the case, it will proceed with no one who supports LEBOR present to argue on behalf of Lake Erie or the citizens of Toledo for the remainder of a case that will decide the fate of a law enacted by the citizens of Toledo. To be clear, the City government, popularly assumed to represent the will of the City’s people, is specifically not representing the will of the people.

About an hour after denying Lake Erie and Toledoans for Safe Water’s intervention, Zouhary scheduled a phone conference for Friday, May 17 while ordering the parties to the lawsuit to send him letters regarding a Motion for Judgment on the Pleadings. Typically, parties to a lawsuit file motions and briefs describing their arguments and these motions and briefs become part of the public record so that the public can see why legal decisions are made. In specifically asking for letters, Zouhary shielded Drewes Farms Partnership’s, the State of Ohio’s, and the City of Toledo’s arguments from public scrutiny. Here we see how the will of the people, expressed through the legislative process, can be effectively silenced by the judicial process. The courts, commonly thought of as a check on abuses of power by the legislative branch of government that encroach on fundamental rights of individuals, have now been unmasked as a vehicle to silence and overturn the will of the people and to legitimize further violations of fundamental rights of the people – in this case the simple and essential right to clean water.

And to round out the evidence that we do not live in a democracy, on Thursday, May 9, the Ohio House of Representatives adopted its 2020-2021 budget with provisions that prohibit anyone, including local governments, from enforcing rights of nature laws. The State of Ohio is using its power of preemption – a long-established legal doctrine that defines the relationship of municipal governments to state and federal governments as one of parent to a child – to prevent Ohio residents from protecting the natural world with rights of nature at any time in the future.

This is a perfect example of why CELDF lawyer and executive director Thomas Linzey often states that, “Sustainability itself has been rendered illegal under our system of law.” And:

“Under our system of law, you see, it doesn’t matter how many people mobilize or who we elect – simply because the levers of law can’t be directly exercised by them. And even when they do manage to swing the smallest of those levers, they get swung back (either through the legislature or the courts) by a corporate minority who claimed control over them a long time ago.”

Toledoans for Safe Water swung “the smallest of those levers” and now they have been “swung back” by both the legislature and the courts in favor of the corporate minority. We see then, that under our current system of laws, there is no government actor that validates and protects the will of the people. In the case of Lake Erie, the City of Toledo, the State of Ohio, two levels of federal courts (the District Court for the District of Ohio and the Sixth Circuit Court of Appeals), have all actively undermined the health and welfare and the express political will of the citizens of Toledo – all in the name of preserving and protecting the freedom of agricultural interests to continue polluting Lake Erie for the sake of their own profits.

***

With it being all but certain that the Lake Erie Bill of Rights will soon be officially invalidated, has Toledoans for Safe Water’s work been in vain?

Not entirely.

“Unquestioned beliefs are the real authorities of a culture,” critic Robert Coombs tells us. Right now, the culture of profit in our country, sanctioned by the legal system is destroying the planet. Informing this dominant culture is a collection of unquestioned beliefs that authorize and allow the massive environmental destruction we currently witness. Stopping the destruction requires changing the dominant culture and changing the dominant culture requires publicly challenging unquestioned beliefs so those unquestioned beliefs are exposed to the light where they can be seen, understood, and condemned.

Perhaps surprisingly, one of the unquestioned beliefs authorizing ecocide is the belief that we live in a democracy and, because we live in a democracy, that our government reflects the will of the governed. This mistaken belief leads to more mistaken beliefs including a belief that the best way to make change is to petition your elected representatives, and if they won’t listen, to elect new ones who will. This misconception includes the further mistaken belief that the American regulatory framework exists to protect the natural world and the humans who depend on Her and that therefore filing lawsuits under the Endangered Species Act, the National Environmental Policy Act, and the Clean Air and Clean Water Acts can stop the destruction of endangered species, our habitat, and the air and water we require.

We should all know the truth, by now. We do not live in a democracy, and our government was never intended to reflect the will of the governed. Our elected representatives only listen to us when the corporations they’re beholden to aren’t telling them what to do. The regulatory framework does not exist primarily to protect the natural world; it exists to issue permits, to give permission, to legalize the harm corporate projects wreak on the natural world, and to make it near impossible for the citizenry to oppose those projects.

Even some of the current government’s most sacred documents, such as the Declaration of Independence, the Ohio State Constitution, as well as many other state constitutions, declare that people have a right to reform, alter, or even abolish the very governments those documents create when those governments fail to reflect the will of the people. The people of Toledo tried to exercise that right by passing LEBOR. Regardless, the very institutions supposedly tasked with honoring these documents are preventing the people from exercising the rights asserted in the Declaration of Independence and protected by the Ohio State Constitution.

We should all know the truth, by now, but most people still don’t. It’s one thing to tell people the truth. And, it’s another to show them. A major question, then, for social and environmental justice advocates is: How do we show people the truth?

One way is through acts of civil disobedience like enacting the Lake Erie Bill of Rights. A primary purpose of civil disobedience is to expose unquestioned beliefs for what they really are. In the case of the regulatory fallacy described above, these unquestioned beliefs serve as propaganda intended to pacify the people. Civil disobedience can stage the truth of our situation for the public to behold. Properly applied, civil disobedience can illuminate unquestioned beliefs and unveil their falsehoods.

CELDF attacks unquestioned beliefs through what it calls “organizing jujitsu.” CELDF helps communities suffering from destructive corporate projects (like fracking, factory farms, and toxic waste storage) ban those projects by passing local laws establishing rights of nature and invalidating judicially-created corporate rights. These laws, however, are currently illegal under American law and are, inevitably, struck down by the courts.

So, why does CELDF keep helping communities pass laws that are almost always struck down? This is where the organizing jujitsu happens. The laws that CELDF helps communities pass are frontal challenges to long-settled legal doctrines. When judges rule against local laws, judges’ rulings can be used as proof of how the structure actually operates. In CELDF’s words:

“Much like using single matches to illuminate a painting in a dark room, enough matches need to be struck simultaneously (and burn long enough) so that the painting can be viewed in its entirety. Each municipality is a match, and each instance of a law being overturned as violative of these legal doctrines is an opportunity for people to see how the structure actually functions. This does the necessary work of penetrating the denial, piercing the illusion of democracy, and removing the blinders that prevent a large majority of people from seeing the reality on the ground.”

With the indicators of ecological collapse constantly intensifying, it is imperative that we penetrate the denial, pierce the illusion of democracy, and remove the blinders that prevent people from seeing reality as quickly as possible. Due to the thoroughness of American indoctrination, the education civil disobedience can provide needs to be supported by real-time commentary that highlights why a specific tactic failed. This real-time commentary will help the public see the truth.

Toledoans for Safe Water has used every legal means at their disposal to protect Lake Erie and, yet, the Lake Erie Bill of Rights is not being enforced and is almost certain to be invalidated in court. Meanwhile, the poisoning of Lake Erie intensifies. Toledoans for Safe Water’s civil disobedience, despite challenging a widespread faith in the American legal system, has failed to physically protect Lake Erie. Breaking this faith is a necessary, but not sufficient, step towards dismantling the dominant culture and replacing it with a new culture rooted in a humble recognition of our dependency on the natural world. For those who see the truth that neither the legal system nor the government will protect us, the question becomes: What are we willing to do to protect ourselves?

—

Will Falk is a biophilic writer and lawyer. He believes the natural world speaks. And, his work is an attempt to listen. In 2017, he helped to file the first-ever federal lawsuit seeking rights of nature for a major ecosystem, the Colorado River. His book How Dams Fall which chronicles his experiences representing the Colorado River in the lawsuit, will be published by HomeBound Publications in October, 2019. You can follow Will’s work at willfalk.org.

Sean Butler is a technology lawyer and environmental activist based in Sequim, WA. In addition to his practice supporting venture-backed startups he is working to advance the rights of nature.

by Deep Green Resistance News Service | Mar 2, 2019 | Agriculture

by Fred Iutzi and Robert Jensen / Resilience.org

Propelled by the energy of progressive legislators elected in the 2018 midterms elections, a “Green New Deal” has become part of the political conversation in the United States, culminating in a resolution in the U.S. House with 67 cosponsors and a number of prominent senators lining up to join them. Decades of activism by groups working on climate change and other ecological crises, along with a surge of support in recent years for democratic socialism, has opened up new political opportunities for serious discussion of the intersection of social justice and sustainability.The Green New Deal proposal—which is a resolution, not a bill, that offers only a broad outline of goals and requires more detailed legislative proposals—will not be successful right out of the gate; many centrist Democrats are lukewarm, and most Republicans are hostile. This gives supporters plenty of time to consider crucial questions embedded in the term: (1) how “Green” will we have to get to create a truly sustainable society, and (2) is a “New Deal” a sufficient response to the multiple, cascading economic/ecological crises we face?

In strategic terms: Should a Green New Deal limit itself to a reformist agenda that proposes programs that can be passed as soon as possible, or should it advance a more revolutionary agenda aimed at challenging our economic system? Should those of us concerned about economic justice and ecological sustainability be realistic or radical?

Our answer—yes to all—does not avoid tough choices. The false dichotomies of reform v. revolution and realistic v. radical too often encourage self-marginalizing squabbles among people working for change. Philosophical and strategic differences exist among critics of the existing systems of power, of course, but collaborative work is possible—if all parties can agree not to ignore the potentially catastrophic long-term threats while trying to enact limited policies that are possible in the short term. Reforms can take us beyond a reformist agenda when pursued with revolutionary ideals. Radical proposals are often more realistic than policies crafted out of fear of going to the root of a problem.

Our proposal for an agricultural component for a Green New Deal offers an example of this approach. Humans need a revolutionary new way of producing food, which must go forward with a radical critique of capitalism’s ideology and the industrial worldview. Reforms can begin to bring those revolutionary ideas to life, and realistic proposals can be radical in helping to change worldviews.

We focus here on two proposals for a Green New Deal that are politically viable today but also point us toward the deeper long-term change needed: (1) job training that could help repopulate the countryside and change how farmers work, and (2) research on perennial grain crops that could change how we farm. Two existing organizations, the Land Stewardship Project in Minnesota and The Land Institute in Kansas, offer models for successful work in these areas.

Philosophy and Politics

We begin by foregrounding our critique of capitalism and the industrial worldview. All policy proposals are based on a vision of the future that we seek, and an assessment of the existing systems that create impediments to moving toward that vision. In a politically healthy and intellectually vibrant democracy, policy debates should start with articulations of those visions and assessments. “Pragmatists”—those who appoint themselves as guardians of common sense—are quick to warn against getting bogged down in ideological debates and/or talk of the future, advising that we must focus on what works today within existing systems. But accepting that barely camouflaged defense of the status quo guarantees that people with power today will remain in power, in the same institutions serving the same interests. It is more productive to debate big ideas as we move toward compromise on policy. Compromise without vision is capitulation.

Green New Deal proposals should not only offer a set of specific policy proposals but also articulate a new way of seeing humans and our place in the ecosphere. At the core of our worldview is the belief that:

- People are not merely labor-machines in the production process or customers in a mass-consumption economy. Economic systems must create meaningful work (along with an equitable distribution of wealth) and healthy communities (along with fulfilled individuals).

- The more-than-human world (what we typically call “nature”) cannot be treated as if the planet is nothing more than a mine for extraction and a dump for wastes. Economic systems must make possible a sustainable human presence on the planet.

These two statements of values are a direct challenge to capitalism and the industrial worldview that currently define the global economy. Fueled by the dense energy in coal, oil, and natural gas, industrial capitalism has been the most wildly productive economic system in human history, but it routinely fails to produce meaning in people’s lives and it draws down the ecological capital of the planet at a rate well beyond replacement levels. Most of the contemporary U.S. political establishment assumes these systems will continue in perpetuity, but Green New Deal advocates can challenge that by speaking to how their proposals meet human needs for meaning-in-community and challenge the illusion of infinite growth on a finite planet.

The Countryside

In an urban society and industrial economy dominated by finance, many people do not think of agriculture as either a significant economic sector or a threat to ecological sustainability. With less than two percent of the population employed in agriculture, farming is “out of sight, out of mind” for most of the population. To deal effectively with both economic and ecological crises, a Green New Deal should include agricultural policies that (1) support smaller farms with more farmers, living in viable rural economies and communities, and (2) advance alternatives to annual monoculture industrial farming, which is a major contributor to global warming and the degradation of ecosystems.

These concerns for the declining health of rural communities and ecosystems are connected. Economic and cultural forces have made farming increasingly unprofitable for small family operations and encouraged young people to view education as a vehicle to escape the farm. The command from the industrial worldview was “get big or get out,” and the not-so-subtle hint to young people has been that social status comes with managerial, technical, and intellectual careers in cities. The economic drivers have encouraged increasingly industrialized agriculture, adding to soil erosion and land degradation in the pursuit of short-term yield increases. The dominant culture tells us that markets know best and advanced technology is always better than traditional methods.

Today one hears of how rural America and its people are ignored, but a more accurate term would be exploited—an “economic colonization of rural America.” Agricultural land is exploited, as are below-ground mineral and water resources, typically in ecologically destructive fashion. Meanwhile, recreation areas are “preserved,” largely for use by city people. The damage done to land and people are, in economists’ vocabulary, externalities—rural people, the land, and its creatures pay costs that are not factored into economic transactions. Responding to the crises in rural America is crucial in any program aimed at building a just and sustainable society.

Farmer Training

Much of the discussion about job training/retraining for a Green Economy focuses on technical skills needed for solar-panel installation, weatherizing homes, etc.—important projects that are politically realistic, culturally palatable, and technologically mature today. But a sustainable future with dramatic reductions in fossil-fuel consumption also requires a redesigned agricultural system, which requires more people on the land. We need the appropriate “eyes-to-acres ratio” that makes it possible to farm in an ecologically responsibly manner, according to Wes Jackson, co-founder of The Land Institute and a leader in the sustainable agriculture movement.

A visionary Green New Deal proposal would, as a first step, provide support for programs to expand farming and farm-related occupations in rural areas, part of a long-term project to repopulate the countryside in preparation for the more labor-intensive sustainable agriculture that we would like to see today and will be necessary for a future with “land-conserving communities and healthy regional economies,” to borrow from The Berry Center. The dominant culture equates urban with the progressive and modern, and rural with the unsophisticated and backward, a prejudice that must be challenged not only in the world of ideas but also on the ground.

The Land Stewardship Project offers a template, with three successful training programs. A four-hour Farm Dreams workshop helps people clarify their motivations to farm and begins a process of identifying resources and needs, with help from an experienced farmer. In farmer-led classroom sessions, on-farm tours, and an extensive farmer network, the Farm Beginnings course is a one-year program designed for prospective farmers with some experience who are ready to start a farm, whether or not they currently own land. The two-year Journeyperson course supports people who have been managing their own farm and need guidance to improve or expand their operation for long-term success.

There are, of course, many other farm-training programs from non-profits, governmental agencies, and educational institutions. We highlight LSP, which was founded in 1982, because of its track record and flexibility in responding to political conditions and community needs, particularly its willingness to engage critiques of white supremacy. Support for such programs is not only sensible policy but, in blunt political terms, a signal that progressives backing a Green New Deal recognize the need to revitalize rural areas, where people often feel forgotten by urban legislators and their constituents.

Perennial Polycultures

There has been growing interest in community-supported agriculture, urban farms, and backyard gardening, all of which are components of a healthy food system and healthy communities but do not address the central challenges in the production of the grains (cereals, oilseeds, and pulses) that are the main staples of the human diet. Natural Systems Agriculture research at The Land Institute—which focuses on perennial polycultures (grain crops grown in mixtures of plants) to replace annual monoculture grain farming—offers a model for the long-term commitment to research and outreach necessary for large-scale sustainable agriculture.

Annual plants are alive for only part of the year and are weakly rooted even then, which leads to the loss of precious soil, nutrients, and water that perennial plants do a better job of holding. Monoculture approaches in some ways simplify farming, but those fields have only one kind of root architecture, which exacerbates the problem of wasted nutrients and water. Current industrial farming techniques (use of fossil-fuel based fertilizers, herbicides, and pesticides, with increasingly expensive and complex farm implements) that are dominant in the developed world, and spreading beyond, also are a major source of greenhouse gas emissions. Less disturbance of soil carbon, in tandem with reduced fossil fuel use in production, reduces the contribution of agriculture to global warming.

Founded in 1976, TLI’s long-term research program has developed Kernza, an intermediate wheatgrass now in limited commercial production, and is working on rice, wheat, sorghum, oilseeds, and legumes, in collaborations with people at 16 universities in the United States and in 18 other countries. Through this combination of perennial species in a diverse community of plants, “ecological intensification” can enhance fertility and reduce weeds, pests, and pathogens, supplanting commercial inputs and maintaining food production while reducing environmental impacts of agriculture.

A visionary Green New Deal could fund additional research into perennial polycultures and other projects that come under the heading of agro-ecology, an umbrella term for farming that rejects the reliance on the pesticides, herbicides, and chemical fertilizers that poison ecosystems all over the world.

Revolution in the Air?

Expanding the number of farmers with the skills needed to leave industrial agriculture behind, and developing crops for a low-energy world are crucial if we are to achieve an ecologically sustainable agriculture. But those changes are of little value without land on which those new farmers can raise those new crops. There is no avoiding the question of land ownership and the need for land reform.

We have no expertise in this area and no specific proposals to offer, but we recognize the importance of the question and the challenge it presents to achieving sustainability in the contemporary United States, as well as around the world. Today, land ownership patterns are at odds with our stated commitment to justice and sustainability—too few people own too much of the agricultural land, and women and people of color are particularly vulnerable to what a Food First report described as, “the disastrous effects of widespread land grabbing and land concentration.”

In somewhat tamer language, the USDA-supported Farmland Information Center reports what is common knowledge in the countryside: “Finding affordable land for purchase or long-term lease is often cited by beginning and expanding farmers and ranchers as their most significant challenge.” Adding to the problem is the loss of farmland to development; in a 2018 report, the American Farmland Trust reported that almost 31 million acres of agricultural land was “converted” between 1992 and 2012.

No one expects any bill introduced in today’s Congress to endorse government action to protect agricultural land from development and redistribute that land to prospective farmers who are currently landless—growing support for democratic socialism does not a revolution make. But any serious long-term planning will have to address land reform, for as the agrarian writer Wendell Berry points out, “There’s a fundamental incompatibility between industrial capitalism and both the ecological and the social principles of good agriculture.”

A vision of rural communities based on family farms is often mistakenly dismissed as mere nostalgia for a romanticized past. We can take stock of the past failures not only of the capitalist farm economy but also of farmers—small family farms are no guarantee of good farming, and rural communities do not guarantee social justice—and still realize that repopulating the countryside is an essential part of a sustainable future.

Conclusion

We began with a faith that people with shared values might disagree about strategies yet still work together. People working on a wide variety of other projects—for example, worker/producer/consumer cooperatives and land trusts—can find reasons to support our ideas, just as we support those projects. But we also recognize that real-world proposals have to prioritize, and so we want to be clear about differences.

For example, the Green New Deal resolution calls for “100 percent of the power demand in the United States through clean, renewable, and zero-emission energy sources.” One of the key groups backing the plan, the Sunrise Movement, calls this one of the three pillars of its program. We believe this is unrealistic. No combination of renewable energy sources can power the United States in its current form. To talk about renewable energy as a solution without highlighting the need for a dramatic decrease in consumption in the developed world is disingenuous. Pretending that we can maintain First World affluence and achieve sustainability will lead to failed projects and waste limited resources.

Many advocates of a Green New Deal focus on renewable energy technologies and other technological responses to rapid climate disruption and ecological crises. These technologies are only part of the solution. We should reject the dominant culture’s “technological fundamentalism”—the illusion that high-energy/high-technology can magically produce sustainability at current levels of human population and consumption. A Green New Deal should support technological innovations, but only those that help us move to a low-energy world in which human flourishing is redefined by improving the quality of relationships rather than maintaining the capacity for consumption.

We understand that short-term policy proposals must be “reasonable”—that is, they must connect to people’s concerns and be articulated in terms that can be widely understood. But they also must help move us toward a system that many today find impossible to imagine: An economy that not only (1) transcends capitalism and its wealth inequality but also (2) rejects the industrial worldview and its obsession with production. Today’s policy proposals should advance egalitarian goals for the economy but also embrace an ecological worldview for society, without turning from the difficulty posed by the dramatic changes that lie ahead.

by Deep Green Resistance News Service | Jun 28, 2018 | Agriculture

by Richard Young – SFT Policy Director / Sustainable Food Trust

Media attention has again highlighted the carbon footprint of eating meat, especially beef, with some journalists concluding that extensive grass-based beef has the highest carbon footprint of all. SFT policy director, Richard Young has been investigating and finds that while the carbon footprint of a year’s consumption of beef and lamb in the UK is high, it is nevertheless responsible for less emissions than SFT chief executive Patrick Holden’s economy class flight to the EAT forum in Stockholm this week.

A recent, very comprehensive, research paper by Poore and Nemecek from Oxford University and Agroscope, a large research company in Switzerland, has again drawn attention to the rising demand for meat, resulting from population growth and increasing affluence in some developing countries. Looked at from a global perspective the figures appear stark. The study claims that livestock production accounts for 83% of global farmland and produces 56-58% of the greenhouse gas emissions from food, but only contributes 37% of our protein intake and 18% of calories. As such, it’s perhaps not so surprising that concerned journalists come up with coverage like the Guardian’s, Avoiding meat and dairy is ‘single biggest way’ to reduce your impact on Earth. This is part of a series of articles, some of which have been balanced, but most of which have largely promoted vegan and vegetarian agendas with little broader consideration of the issues.

The question of what we should eat to reduce our devastating impact on the environment, while also reducing the incidence of the diet-related diseases which threaten to overwhelm the NHS and other healthcare systems, is one of the most important we face. Yet, the debate so far has been extremely limited and largely dominated by those with little if any practical experience of food production or what actually constitutes food system sustainability.

I’ve lost count of the number of food campaigners who’ve told me that all we need to do to make food production sustainable is to stop eating meat. Really? What about the environmental impact of palm oil, soya bean oil, rape oil and even sunflower oil production; the over-enrichment of the environment from nitrogen fertiliser; the decline in pollinating insects; the use of pesticides with known harmful impacts that would have been banned years ago were it not for the fact that intensive crop and vegetable growers can’t produce food without them?

What also about the growing problem of soil degradation, not just in the countries from which we import food, but right here in the UK? Environment Secretary Michael Gove himself has warned that we are 30-40 years away from running out of soil fertility on large parts of our arable land. With only minor exceptions, soil degradation is not a problem on UK grasslands.

Contrary to popular belief, continuous crop production is not sustainable. That’s the mistake made by the Sumerians 5,000 years ago in what is now Iraq, and the Romans in North Africa 2,000 years ago, and in both cases the soils have never recovered. Far from abandoning livestock farming on UK grassland, we actually need to reintroduce grass and grazing animals into arable crop rotations. Despite the drop in demand for red meat in the UK (beef consumption down 4% and lamb consumption down more than 30% since 2000), at least one leading conventional farmer has now publicly recognised the agronomic need for grazed grass breaks. Even before there has been any encouragement in policy, I am aware that some arable farmers are already being forced to re-introduce grass and livestock because they can no longer control arable weeds like blackgrass, sterile brome and couch (twitch), which have become resistant to the in-crop herbicides repeatedly applied to them in all-arable rotations.

Grazing livestock and nature conservation

Seemingly oblivious of these issues, George Monbiot in The best way to save the planet? Drop meat and dairy, on Friday, June 8, also used the research study as evidence to support his claim that if we all gave up meat and dairy we’d be able to re-wild grasslands and live happily by eating more imported soya. Giving up livestock farming would, he believes, allow “many rich ecosystems destroyed by livestock farming to recover, absorbing carbon dioxide from the atmosphere, protecting watersheds and halting the sixth great extinction in its tracks.”

He quoted a passage from the Poore and Nemecek research paper which states that the environmental impacts of converting grass into human-edible protein are “immense under any production method practiced today”. However, ‘immense’ is a subjective adjective. There are many things we do which have far higher negative impacts, most of which are non-essential and do not bring with them the unique benefits that come from grazing animals. Letters responding to the Guardian’s series of articles drew attention to some of these, including issues previously publicised by the Guardian itself.

What about meat and wildlife?

It’s true, and a very great concern, that human activity is destroying the natural world in a completely unsustainable way. The growing of grain crops specifically for intensive livestock is clearly part of the problem, as is highly intensive grassland farming. However, blaming meat consumption so specifically lets an awful lot of practices off the hook. When one considers the rabbits, hares, deer, moles and wild birds killed each year to protect food crops, and the decline in hedgehog and other small mammal numbers since the 1950s – in part due to the removal of hedgerows to make fields larger for crop production – plant-based diets could even be responsible for the deaths of as many mammals and birds as animals slaughtered from the livestock sector.

Since we were (mistakenly in my view) encouraged to switch from animal to vegetable fats 35 years ago, we’ve also consumed and used ever-greater quantities of palm oil from south-east Asia. Its production has been responsible for the near annihilation of many species, including orangutans, pigmy elephants and Sumatran elephants, rhinos and tigers. With demand still growing, similar pressures are now building in equatorial countries in Africa and South America where palm oil production is also taking off. The scientists behind some of the most recent research on species decline blame “human overpopulation and continued population growth, and overconsumption, especially by the rich”, rather than livestock production specifically.

The importance of livestock grazing for wild plants and animals

We also need to remember that many important plant and wildlife species have evolved in tandem with grazing animals and depend on them for their survival, a point made very strongly by Natural England in their report, The Importance of Livestock Grazing for Wildlife Conservation. This is a key reason why the RSPB uses cattle on its reserves, and states that livestock farming is “essential to preserving wildlife and [the] character of iconic landscapes”. And while overgrazing, encouraged by poorly conceived support schemes, has been a problem in the past, the RSPB is concerned that “undergrazing is now occurring in some areas, with adverse impacts on some species, such as golden plover”, while also “contributing to the spread of ranker grasses, rush, scrub and bracken”. Extensively grazed grasslands also have a wide range of additional benefits. They purify drinking water better than any other land use, and they provide food for pollinating insects at times of year when there is little else available. They also store vast amounts of carbon, which if released through conversion to continuous crop production, would accelerate global warming even faster than it is currently occurring.

Food security

Livestock production may only provide 37% of total protein globally, but it clearly provides significantly more than that in the UK. Two-thirds of UK farmland – if we include common land and rough grazing – is under grass, most of that for important environmental reasons. Only 12% of this (8% of total farmland) is classified as arable, meaning that it may, under current EU rules, be ploughed for cropping. Much of this is on farms which grow grass in rotation with crops to build fertility naturally and control weeds, pests and diseases, so when one field of arable grassland is ploughed up another is generally re-sown with grass. If we were to stop grazing cattle and sheep on this land, we would greatly reduce our food security and make ourselves vulnerable, if, for example, extreme weather due to climate change, or a new crop disease were to reduce global soya yields. We would also need to import a very great deal more food, because as I have previously shown, cattle consume only about 5% of the 3.1 million tonnes of soya oil, beans and meal we import (1.1 million tonnes of the 3.1 million tonnes imported is fed to livestock, of which cattle consume only 15%) and sheep consume very little indeed.

The problem with global averages

So far, I’ve rather ducked the key issue of the greenhouse gas emissions from livestock production. Before we can make much progress on this we need first to consider the issue of global average emission figures. Looking at global averages and drawing conclusions from them isn’t actually very helpful. Essentially a small proportion of grazing livestock animals cover a high proportion of the land area and emit a high proportion of the greenhouse gases, while producing only a very small proportion of the meat and milk. The authors of the research paper say, “For many products, impacts are skewed by producers with particularly high impacts…..for beef originating from beef herds, the highest impact 25% of producers represent 65% of the beef herds’ GHG emissions and 61% of land use.”

Simplistically, we might think the obvious answer is to eliminate the 25% of producers who are causing such a large part of the problem. However, this 25% of producers mostly live in dryland regions, such as Sub-Saharan Africa, areas which often have very poor soils and low rainfall. As such their animals grow very slowly, but it is claimed, still produce a lot of methane, because they have to eat very poor-quality herbage. No doubt, people living in the Global South could reduce their carbon footprint from food significantly if they gave up meat and dairy, but they would also very quickly starve.

Approximately a quarter of the global population live in dryland regions where severe droughts are an ever-present threat. Farming families, depending entirely on crops, would have no food at all when the rains fail. In contrast, animals put on flesh in the better years and provide a substantial buffer against starvation, since they can be slaughtered and eaten one by one over significant periods of time in drought years. It also has to be pointed out that unlike many of us in the Global North, who mostly have cars, central heating and fly abroad, the emissions associated with meat consumption in the drylands in the Global South are more or less the only carbon footprint these people have, and amount to just a small fraction of our own.

This aspect also helps us to see how misleading even the headlines on the percentage of land used for livestock production can be, when the very large areas of land in dryland regions are averaged with the grasslands in more fertile regions.

It is also significant that global averages cited by the UN’s Food and Agriculture Organisation in Livestock’s Long Shadow in 2006 (and two other reports in 2013) were dramatically increased by the inclusion of the emissions associated with the destruction of rainforest and virgin land for cattle grazing and soya production, most of which took place before 2005. These were tragic events with multiple causes, but ones which have little relevance to grazing livestock production and beef consumption in the UK, where the predominant land use changes occurring at the time were entirely in the opposite direction – the conversion of grassland to crop production and the planting of trees.

Beef and sheep production in Northern Europe, especially the UK and Ireland, is highly productive and this greatly reduces the carbon footprint of beef and lamb in these regions. These countries have climates and soil types ideally suited to growing grass and only marginally suited to crop production. So using global average figures for the UK also tells us nothing of value.

The scientific debate

I have written to a number of scientists about these issues over the last week, including one of the authors of the research paper, Joseph Poore. Both he and I recognise that there are huge differences in the emissions associated with beef produced in different production systems and that an objective should be to improve systems, wherever possible, to reduce their carbon footprint. While the headlines have focused on the worst examples – beef linked to emissions of between 40 and 210 kg of carbon dioxide (CO2) per kilo – the research study does actually provide data for the second most productive category of beef production which emit 18.2 kg of CO2 per kilo of beef produced.

For anyone not familiar with how these figures are obtained it may help to know that despite being expressed in terms of the greenhouse gas (GHG) CO2, the emissions from beef mostly relate to methane (CH4) and to a lesser extent nitrous oxide (N2O). In order to compare emissions from different sources, these are expressed in terms of CO2 equivalent, based on the relative global warming impacts of the different GHGs, CH4 and N2O, approximately 30 and 300 times higher, respectively, than CO2.

The figures cited in the research paper are global close-to-best, overall average and close-to-worst, but in correspondence, Poore has helpfully given me further information, which shows that beef from the UK dairy herd is typically responsible for emissions in the range 17-27 kg CO2 per kilo. I’ll express this as an average of 22kg CO2 per kilo of beef to make the calculations later on, less complex. While it is generally assumed that dairy beef has lower emissions than suckler beef, and that could be the case on farms with late maturing cattle, figures for the 100% organic grass-fed beef produced on my own farm suggest that emissions are no higher than 17 kg per kilo of beef, and may even be lower – I can’t do a complete calculation because I don’t have figures for all aspects, for example, the electricity costs at the abattoir where our animals are slaughtered and refrigerated before being brought back to our butchers shop, or the GHG costs of making our hay.

Methane

Despite all this, we cannot pretend that the direct greenhouse gases from grass-fed beef are insignificant. Nevertheless, methane (CH4) breaks down (largely in the atmosphere, and to a lesser extent in soils not receiving ammonium-based nitrogen fertilisers) to CO2 and water after about 10 years. If we contrast grassland with little or no nitrogen fertiliser use with food systems which depend heavily on nitrogen fertiliser, the carbon in the CO2 and the CH4 from grass-fed ruminants is recycled, not fossil, carbon. Ruminants can’t add more to the atmosphere than the plants they eat can photosynthesise from the atmosphere.

The high methane levels in the atmosphere are a very serious problem, but they have become a problem not so much because of cattle and sheep – the numbers of which have increased only modestly over the last 40 years – but because of fossil fuels. Taken together, the fossil fuels, oil, natural gas and coal are not only by far the biggest source of the major GHG CO2, they are also responsible for about a third more methane emissions than ruminants – and all the carbon in that CH4 is, of course, additional carbon that has been stored away deep underground for the last 400 million years. That’s all based on long-established data. But a more recent study analysing the relative amounts of the isotopes carbon12 and carbon14, which vary according to the source of the methane, has found that scientists have previously under-estimated methane emissions from fossil fuels by 20-60% and over-estimated those from microbial sources, such as the rumen bacteria which produce methane, by 25%. That doesn’t affect the figures in Poore and Nemecek’s paper, but it does help us to see more clearly the relative importance of reducing fossil fuel use compared with red meat consumption. In that respect, re-localising food systems, discouraging supermarkets from centralising their distribution networks, consuming the foods most readily produced in the UK and minimising imports would surely be a good start?

Soil carbon sequestration

Unlike some leading campaigners and scientists who call for big reductions in ruminant numbers and largely dismiss the significance of soil carbon sequestration, Poore and Nemecek accept that carbon sequestration under grassland can, under certain circumstances, for a finite period, offset a significant proportion of the emissions from cattle and sheep. According to them the maximum extent of this is a reduction of just over one-fifth (22%) of the emissions. However, since they cite no UK-specific data in their study it is not clear whether this has any relevance to the UK or whether it is simply a global average.

About half of soil organic matter is made up of carbon. The rest is mostly nitrogen and water. Organic matter is critically important to long term soil resilience and water-holding ability. The general assumption amongst scientists is that organic matter levels fall, year on year when grassland is converted to cropland, and eventually stabilise at a new lower level on clay-based soils after a century or more. Peat-based and sandy soils are an exception as. In contrast, the conversion of croplands to grass will rebuild that carbon over broadly the same period. Overstocked land will also lose carbon. Ley/arable rotations will see levels go up and down depending on the phase of the rotation and the proportion of arable to grass crops.

As such, long-established, many well managed soils under permanent grassland in the UK are probably already close to their maximum potential level of carbon. However, virtually all heavily stocked UK grasslands have the potential to sequester more carbon if their management is improved and all croplands could steadily regain carbon if they were converted to grass or to rotations including grass breaks. Since a third of soils globally are significantly degraded and another 20% moderately degraded the global potential for carbon sequestration is considerable.

Confusion has arisen due to the very significant variation between the rates of sequestration found in many studies. However, a review of 42 studies in 2014 found that more than half these differences could be explained by considering whether or not livestock manures were returned to the land. It seems likely, based on other research, that much of the remaining differences will relate to land management, stocking levels and precipitation levels. Deeper rooting grasses, legumes and herbs also have the potential to increase carbon down to much greater depths than the most widely used ryegrasses which are shallow-rooting.

Undertaking a calculation

Can we find a way of relating the emissions associated with beef to other things we do to get some idea of their relative significance? I’ll use the average 22 kg of CO2 for beef from the UK dairy herd (established above) as it’s the only solid figure I have for the UK. In 2015 and 2016, according the AHDB’s UK yearbook – cattle, average beef consumption per person in the UK was 18.2 kg and average consumption of lamb was 4.9 kg. So we can now undertake a calculation to establish the carbon footprint of a typical beef and lamb consumer.

- Beef 18.2 x 22 = 400.4 kg carbon dioxide equivalent

- Lamb 4.9 x 25 = 122 kg carbon dioxide equivalent (based on figures in the study)

On this basis an average British beef and lamb consumer is responsible for the equivalent of 522 kg of CO2, as a result of their red meat consumption. This doesn’t of course include the emissions associated with chicken and pork, but to get some idea of whether giving up red meat is the single most important thing you can do to save the planet, I used an online calculator to work out how much CO2 was emitted as a result of SFT chief executive Patrick Holden’s return flight from Heathrow to Stockholm for the 2018 EAT forum this week. That comes to 466 kg of CO2. Undertaking a similar exercise for the round trip journey by car from his farm in Wales to Heathrow adds another 110 kg, making a total of 576 kg carbon dioxide, for one trip to a nearby country, compared with 522 kg for a whole year’s worth of red meat eating.

One question which therefore arises from this is whether the repeated focus on red meat as a source of global warming is misleading the entire population into assuming that providing they don’t eat red meat they can travel abroad as much as they like with a clear conscience? It’s of note that a roundtrip from Heathrow to San Francisco is equivalent to about 5 year’s-worth of beef and lamb produced in the UK – and quite a few of the vegetarian and vegan campaigners at the EAT forum had come from the US.

Why we need grazing livestock

More than all these issues, however, the SFT defends the role of grazing animals, as we know from years of practical farming experience that systems with cattle or sheep at their core are able to remain highly productive, repair degraded soils and avoid the GHG emissions associated with the manufacture of nitrogen fertiliser, equivalent to about 8 tonnes of CO2 for every tonne of nitrogen used. Farmers growing bread-making wheat and oilseed rape in the UK use up to 250 kg of nitrogen per hectare, meaning that each hectare puts GHGs equivalent to 2 tonnes of CO2 into the atmosphere, just in relation to nitrogen. About half of this nitrogen is lost to the environment and has a wide range of negative impacts on soils, water, the air and on our health. This diffuse pollution has major negative costs for society, estimated by scientists to be 2-3 times higher than the commercial benefits farmers get from using nitrogen fertiliser.

In contrast, using forage legumes, like clover, instead, allows nitrogen to be built up in the soil under grazing swards without any GHG emissions. This can then be exploited to grow crops in subsequent years, before going back to grass and clover. Such grassland systems are almost as productive as those using the highest rates of nitrogen fertiliser. Grain yields are lower, but if we move away from grain-fed livestock that won’t matter. Grain legumes like beans and peas do also fix some nitrogen naturally, but it is not enough to make a significant contribution to reducing nitrogen use in subsequent crops. In addition, not all cropland in the UK is suitable for growing peas, and it’s not possible to grow beans more than one year in five, even with repeated applications of herbicides, fungicides and insecticides.

In conclusion

Clearly there are significant emissions associated with meat production, and it may well be that, in general, grass-fed beef has slightly higher direct emissions than grain-fed beef. I can see big advantages, both environmental and ethical in reducing the production and consumption of grain-fed meat, be it chicken, pork or beef. But there is an overwhelmingly important case why we should continue to produce and eat meat from animals predominantly reared on grass, especially when it is species-rich and not fertilised with nitrogen out of a bag.

Yet, while a few farmers are trying their best to counter the prevailing trends by producing organic or grass-fed meat, far more cattle are now being housed in American-style feedlots, as recently exposed by the Guardian. Ironically this trend is occurring largely due to the failure of scientists, journalists and campaigners to understand the full significance of the differences between farming systems, and therefore the red meat which brings major benefits as well as a few negative impacts, compared with that which only has negative impacts. Due to falling demand for red meat, smaller, more traditional farmers are being forced to choose between giving up – something which has now affected tens of thousands of them – and intensifying, in order to cut costs and stay in business. I very much hope we can find a way to broaden understanding of these issues, because if we can’t, we will see the further spread of most intensive beef systems and we will lose the iconic pastoral character of the British countryside.

Copyright © 2018 with Richard Young, republished with permission. The Sustainable Food Trust is a UK registered charity, charity number 1148645. Company number 7577102.

by Deep Green Resistance News Service | Jun 22, 2018 | Agriculture

Legislation Guts Endangered Species Act, Clean Water Act, Public Lands Protections

by Center for Biological Diversity

WASHINGTON— In a narrow vote, on June 21 the U.S. House of Representatives passed a 2018 Farm Bill that contains an unprecedented provision that would allow the killing of endangered wildlife with pesticides.

With every Democrat and 20 Republicans voting in opposition, H.R. 2, the so-called Agriculture and Nutrition Act of 2018, passed by a vote of 213 to 211. Two Republicans abstained from voting.

“House Republicans just put killer whales, frogs and hundreds of other species on the fast track to extinction,” said Brett Hartl, government affairs director at the Center for Biological Diversity. “This is a stunning gift to the pesticide industry with staggeringly harmful implications for wildlife.”

The legislation would also eliminate the requirement that the U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service analyze a pesticide’s harm to the nation’s 1,800 protected species before the Environmental Protection Agency can approve it for general use. A separate provision would eliminate the Clean Water Act’s requirement that private parties applying pesticides directly into lakes, rivers and streams must first obtain a permit.

During this session of Congress, the pesticide industry has spent more than $43 million on congressional lobbying to advance these provisions.

In addition to giveaways to the pesticide industry, H.R. 2 includes a sweeping provision that would gut environmental protections for national forests to expedite logging and mining, including eliminating nearly all protections for old-growth forests in Alaska. The legislation contains nearly 50 separate provisions that would eliminate all public input in land-management decisions provided by the National Environmental Policy Act.

“This farm bill should be called the Extinction Act of 2018,” said Hartl. “If it becomes law, this bill will be remembered for generations as the hammer that drove the final nail into the coffin of some of America’s most vulnerable species.”

by DGR News Service | Jan 16, 2018 | Agriculture

Agriculture did not arise from need so much as it did from relative abundance. People stayed put, had the leisure to experiment with plants, lived in coastal zones where floods gave them the model of and denizens of disturbance, built up permanent settlements that increasingly created disturbance, and were able to support a higher birthrate because of sedentism.

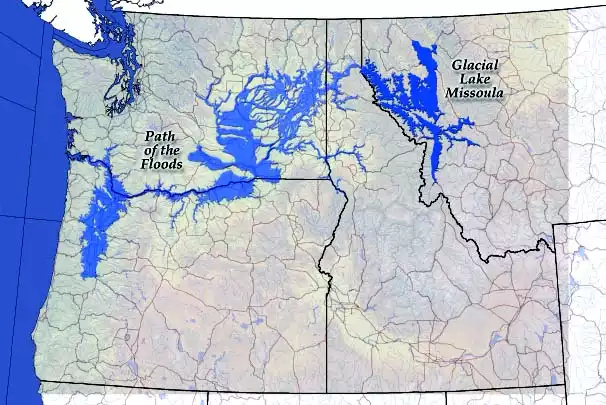

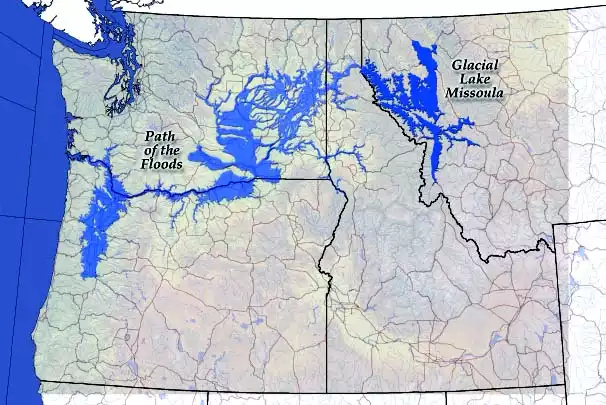

Area altered by Glacial Lake Missoula floods.

In the Middle East, this conjunction of forces occurred about ten thousand years ago, an interesting period from another angle. That date, the start of what is called the Neolithic Revolution, also coincides closely with the end of the last glaciation. As I write this, I sit in a spot that was then at the bottom of a huge lake. I live in a valley that held a lake famous to geologists, glacial Lake Missoula. The valley was formed by an ice dam that sat a couple hundred miles from here, and as the glaciers melted, the ice dam broke and re-formed many times, each time draining in a few hours a body of water the size of today’s Lake Michigan. That’s disturbance. The record of these floods can be clearly read today in giant washes and blowouts throughout the Columbia River basin in Washington State. Within the mouth of the Columbia River, several hundred miles downstream, is a twenty-five-mile-long peninsula made of sand washed downstream in these floods.

When the glaciers retreated, such catastrophic events were happening with increased frequency in floodplains around the world, especially in the Middle East. Juris Zarins of the University of Missouri has suggested that these massive disturbances and floods underlie the central Old Testament myths—the great flood, but also the Garden of Eden. Following a specific description in Genesis of the site of Eden, Zarins traces what he speculates are the four rivers of the Tigris and Euphrates system mentioned there. They would have converged in what is now the Persian Gulf, but during glaciation this would have been dry land. Further, it would have been an enormously productive plain, the sort of place that would have naturally produced an abundance of food without farming.

We call it the Garden of Eden, but it was not a garden; it was not cultivated. In fact, in Genesis, God is vengeful and specific in throwing Adam and Eve out of paradise; his punishment is that they will begin gardening. Says God, “In the sweat of thy face shalt thou eat bread, till thou return unto the ground.” God made good on his threat, and the record now shows just how angry he was. The children of Adam and Eve would hoe rows of corn. “To condemn all of humankind to a life of full-time farming, and in particular, arable farming, was a curse indeed,” writes Colin Tudge.

At about the same time that the shapes of seeds and of butchered sheep bones were changing, so were the shapes of villages and graves. Grave goods—tools, weapons, food, and comforts—were by then nothing new in the ritual of human burials. There is even some evidence, albeit controversial, that Neanderthals, an extinct branch of the family, buried some of their dead with flowers. Burial ritual was certainly a part of hunter-gatherer life, but the advent of agriculture brought changes.

For instance, one of the world’s richest collections of early agricultural settlements lies in the rice wetlands of China’s Hupei basin on the upper Yangtze River. The region was home to the Ta-hsi culture that domesticated rice between 5,500 and 6,000 years ago. Excavation of 208 graves there found many empty of anything but the dead, while others were elaborately endowed with goods. The same pattern emerges worldwide, one of the key indicators that, for the first time in human history, some people were more highly regarded than others, that agriculture conferred social status—or, more important, more goods—to a few people.

Some of early agriculture’s graves contained headless corpses, corresponding to archaeologists finding skulls in odd places and conditions. Skulls in the Middle East, for instance, were plastered to floors or into special pits. Some of the skulls had been altered to appear older. Archaeologists take this as a sign of ancestor worship, reasoning that because of the permanent occupation of land, it became important to establish a family’s claim on the land, and veneration of ancestors was a part of that process. So, too, was a rise in the importance of the family as opposed to the entire tribe, a switch that further evidence bears out.

Coincident with this was a shift in the villages themselves. Small clutches of simple huts gave way to larger collections, but with a qualitative change as well. Some houses became larger than others. At the same time, storage bins, granaries, began to appear. Cultivated grain, more so than any form of food humans had consumed before, was storable, not just through the year, but from year to year. It is hard to overstate the importance of this simple fact as it would play out through the centuries, later making possible such developments as, for instance, the provisioning of armies. But the immediate effect of storage was to make wealth possible. The big granaries were associated with the big houses and the graves whose headless skeletons were endowed with a full complement of grave goods.

Reconstruction of the tomb of King Midas; Museum of Anatolian Civilizations, Ankara, Turkey

The Museum of Anatolian Civilizations in Ankara, Turkey, holds one of the world’s most impressive assemblages of early agricultural remnants, including a reconstruction of a grave from a nearby city once ruled over by King Midas. He was a real guy, and his region was indeed known for its wealth in gold, taken from the Pactolus River. Yet the grave unearthed at Gordium (home of the Gordian knot) once thought to be Midas’s (but now identified as that of another in his line) was not full of gold. It was full of storage vessels for grain.

Of course to assert that agriculture’s grain made wealth possible is to assert that it also created poverty, a notion that counters the just-so story. The popular contention is that agriculture was an advance, progress that enriched humanity. Whatever the quality of our lives as hunter-gatherers, our numbers had become such that hunger forced this efficiency. Or so the story goes.