![“May the truth be your armor” [Excerpts from Bright Green Lies]](https://dgrnewsservice.org/wp-content/uploads/sites/18/2021/05/BGL.jpeg)

by DGR News Service | May 11, 2021 | Biodiversity & Habitat Destruction, Climate Change, Education, Listening to the Land, Mining & Drilling, Strategy & Analysis, The Problem: Civilization, Toxification

This prologue is the first of a series of excerpts we will publish from the new book Bright Green Lies.

PROLOGUE

By Lierre Keith

We are in peril. Like all animals, we need a home: a blanket of air, a cradle of soil, and a vast assemblage of creatures who make both. We can’t create oxygen, but others can–from tiny plankton to towering redwoods. We can’t build soil, but the slow circling of bacteria, bison, and sweetgrass do.

But all of these beings are bleeding out, species by species, like Noah and the Ark in reverse, while the carbon swells and the fires burn on. Five decades of environmental activism haven’t stopped this. We haven’t even slowed it. In those same five decades, humans have killed 60 percent of the earth’s animals. And that’s but one wretched number among so many others.

That’s the horror that brings readers to a book like this, with whatever mixture of hope and despair. But we don’t have good news for you. To state it bluntly, something has gone terribly wrong with the environmental movement.

Once, we were the people who defended wild creatures and wild places. We loved our kin, we loved our home, and we fought for our beloved. Collectively, we formed a movement to protect our planet. Along the way, many of us searched for the reasons. Why were humans doing this? What could possibly compel the wanton sadism laying waste to the world? Was it our nature or were only some humans culpable? That analysis is crucial, of course. Without a proper diagnosis, correct treatment is impossible. This book lays out the best answers that we, the authors, have found. We wrote this book because something has happened to our movement. The beings and biomes who were once at the center of our concern have been disappeared. In their place now stands the very system that is destroying them. The goal has been transformed:

We’re supposed to save our way of life, not fight for the living planet; instead, we are to rally behind the “machines making machines making machines” that are devouring what’s left of our home.

Committed activists have brought the emergency of climate change into broad consciousness, and that’s a huge win as the glaciers melt and the tundra burns. But they are solving for the wrong variable. Our way of life doesn’t need to be saved. The planet needs to be saved from our way of life.

There’s a name for members of this rising movement: bright green environmentalists. They believe that technology and design can render industrial civilization sustainable. The mechanism to drive the creation of these new technologies is consumerism. Thus, bright greens “treat consumerism as a salient green practice.”1

Indeed, they “embrace consumerism” as the path to prosperity for all.2 Of course, whatever prosperity we might achieve by consuming is strictly time limited, what with the planet being finite. But the only way to build the bright green narrative is to erase every awareness of the creatures and communities being consumed. They simply don’t matter. What matters is technology. Accept technology as our savior, the bright greens promise, and our current way of life is possible for everyone and forever. With the excised species gone from consciousness, the only problem left for the bright greens to solve is how to power the shiny, new machines.

It doesn’t matter how the magic trick was done. Even the critically endangered have been struck from regard. Now you see them, now you don’t: from the Florida yew (whose home is a single 15-mile stretch, now under threat from biomass production) to the Scottish wildcat (who number a grim 35, all at risk from a proposed wind installation). As if humans can somehow survive on a planet that’s been flayed of its species and bled out to a dead rock. Once we fought for the living. Now we are told to fight for their deaths, as the wind turbines come for the mountains and solar panels conquer the deserts.

“May the truth be your armor” urged Marcus Aurelius. The truths in this book are hard, but you will need them to defend your beloved. The first truth is that our current way of life requires industrial levels of energy. That’s what it takes to fuel the wholesale conversion of living communities into dead commodities. That conversion is the problem “if,” to borrow from Australian anti-nuclear advocate Dr. Helen Caldicott, “you love this planet.” The task before us is not how to continue to fuel that conversion. It’s how to stop it.

The second truth is that fossil fuel–especially oil–is functionally irreplaceable. The proposed alternatives–like solar, wind, hydro, and biomass–will never scale up to power an industrial economy.

Third, those technologies are in their own right assaults against the living world. From beginning to end, they require industrial-scale devastation: open-pit mining, deforestation, soil toxification that’s permanent on anything but a geologic timescale, the extirpation and extinction of vulnerable species, and, oh yes, fossil fuels. These technologies will not save the earth. They will only hasten its demise.

And finally, there are real solutions. Simply put, we have to stop destroying the planet and let natural life come back. There are people everywhere doing exactly that, and nature is responding, some times miraculously. The wounded are healed, the missing reappear, and the exiled return. It’s not too late.

I’m sitting in my meadow, looking for hope. Swathes of purple needlegrass, silent and steady, are swelling with seeds–66 million years of evolution preparing for one more. All I had to do was let the grasses grow back, and a cascade of life followed. The tall grass made a home for rabbits. The rabbits brought the foxes. And now the cry of a fledgling hawk pierces the sky, wild and urgent. I know this cry, and yet I don’t. Me, but not me. The love and the aching distance. What I am sure of is that life wants to live. The hawk’s parents will feed her, teach her, and let her go. She will take her turn–then her children, theirs.

Every stranger who comes here says the same thing: “I’ve never seen so many dragonflies.” They say it in wonder, almost in awe, and always in delight. And there, too, is my hope. Despite everything, people still love this planet and all our kin. They can’t stop themselves. That love is a part of us, as surely as our blood and bones.

Somewhere close by there are mountain lions. I’ve heard a female calling for a mate, her need fierce and absolute. Here, in the last, final scraps of wilderness, life keeps trying. How can I do less?

There’s no time for despair. The mountain lions and the dragonflies, the fledgling hawks and the needlegrass seeds all need us now. We have to take back our movement and defend our beloved. How can we do less? And with all of life on our side, how can we lose?

1. Julie Newman, Green Ethics and Philosophy: An A-to-Z Guide (Thousand Oaks, CA: SAGE Publications, 2011), p. 40.

2. Ibid, p. 39

![Will Thacker Pass, At Last, Be Still? [Dispatches from Thacker Pass]](https://dgrnewsservice.org/wp-content/uploads/sites/18/2021/05/SnowAtThackerPass-980x735-1.jpg)

by DGR News Service | May 5, 2021 | Biodiversity & Habitat Destruction, Indigenous Autonomy, Listening to the Land, Mining & Drilling, Movement Building & Support, Obstruction & Occupation, Repression at Home, Toxification

On a late April morning in Thacker Pass, where some Paiute ancestors have been buried and some massacred, where some people want to dig out the dead to dig out lithium, I woke to a strange, wet snow that fell overnight a day before temperatures in the 70s were forecast. It seemed a bad omen.

By Will Falk

Paiute elders teach that very bad things happen when the dead are disturbed. I knew this must be true. So many industrial projects in so many places have destroyed so many burial sites. The cracked bones of the slain have been cracked again and again in the frantic search for coal. Old, spilled blood turned to soil has been mixed with new, spilled blood by those who murder for oil. Now, in Nevada, if the lithium miners have their way, those brave Paiute who died resisting American soldiers will finally be forced onto the reservation when machinery agitates the dust formed by those Paiute bodies and the wind blows that dust to coat the homes of Paiute descendants at Fort McDermitt.

Either these desecrations have caused the world to go to hell or the dead, disturbed, have brought hell to Earth.

I pondered this while pondering the surreality of the spring snow. As heavy as it was, the snow didn’t weigh the ghosts down. Fingers that once clawed with shock at bullet holes, clawed through mud made by their own blood. The ghosts climbed through the sage brush roots and volcanic rocks, to drift over the snow and confront the living with the reality of history. Moans moved with heavy clouds. Screams, sometimes, did too. Raven wings stirred the death hanging on the air. The wind blew with their last words in a language I never knew.

Though the language was strange to me, the meaning was clear enough: each generation’s missing and murdered grieve for the next. A meadowlark, landed on the tip of a nearby sagebrush, and began to sing. He sang: “While there’s still time for some, there’s no time for grief.” He told me to let them grieve.

I threw some cedar on the fire and watched my prayers rise with the smoke. I wondered what the wind will do when there are no more dying words to deliver, what the dead will do when they are confident they will not be disturbed, what the ghosts will do when their lessons are remembered. I wondered: Will Thacker Pass, at last, be still?

You can find out more and support Thacker Pass:

by DGR News Service | May 4, 2021 | Biodiversity & Habitat Destruction, Climate Change, Listening to the Land, Mining & Drilling, Movement Building & Support, Toxification

In this article Rebecca Wildbear talks about how civilization is wasting our planet’s scarce water sources for mining in its desperate effort to continue this devastating way of life.

By Rebecca Wildbear

Nearly a third of the world lacks safe drinking water, though I have rarely been without. In a red rock canyon in Utah, backpacking on a week-long wilderness training in my mid-twenties, it was challenging to find water. Eight of us often scouted for hours. Some days all we could find to drink was muddy water. We collected rain water and were grateful when we found a spring.

Now water is scarce, and the demand for it is growing. Globally, water use has risen at more than twice the rate of population growth and is still increasing. Ninety percent of water used by humans is used by industry and agriculture, and when groundwater is overused, lakes, streams and rivers dry up, destroying ecosystems and species, harming human health, and impacting food security. Life on Earth will not survive without water.

In the Navajo Nation in Arizona, Utah, and New Mexico, a third of houses lack running water, and in some towns, it is ninety percent. Peabody Energy Corporation, the largest coal producer and a Fortune 500 company, pulled so much water from the Navajo aquifer before closing its mining operation that many wells and springs have run dry. Residents now have to drive 17 miles to wait in line for an hour at a communal well, just to get their drinking water.

Worldwide, the majority of drinkable water comes from underground reservoirs called aquifers. Aquifers feed streams, lakes, and rivers, but their waters are finite. Large aquifers exist beneath deserts, but these were created eons ago in wetter times. Expert hydrologists say that like oil, once the “fossil” waters of ancient reservoirs are mined, they are gone forever.

Peabody’s Black Mesa Mine extracted, pulverized, and mixed coal with water drawn from the Navajo aquifer to form a slurry. This was sent along a 273-mile-long pipeline to the Mojave Generating Station in Laughlin, Nevada, to power Los Angeles. Every year, the mine extracted 1.4 billion gallons (4,000+ acre feet) of water from the aquifer, an estimated 45 billion gallons (130,000+ acre feet) in all.

Pumping out an aquifer draws down the water level and empties it forever. Water quality deteriorates and springs and soil dry out. Agricultural irrigation and oil and coal extraction are the biggest users of waters from aquifers in the U.S. Some predict that the Ogallala aquifer, once stretching beneath five mid-western states, may be able to replenish after six thousand years of rainfall.

Rain is the most accurate measure of available water in a region, yet over-pumping water beyond its capacity to refill is widespread in the western U.S. and around the world. The Middle East ran out of water years ago—it was the first major region in the world to do so. Studies predict that two thirds of the world’s population are at risk of water shortages by 2025. As ground water levels fall, lakes, rivers, and streams are depleted, and the land, fish, trees, and animals die, leaving a barren desert.

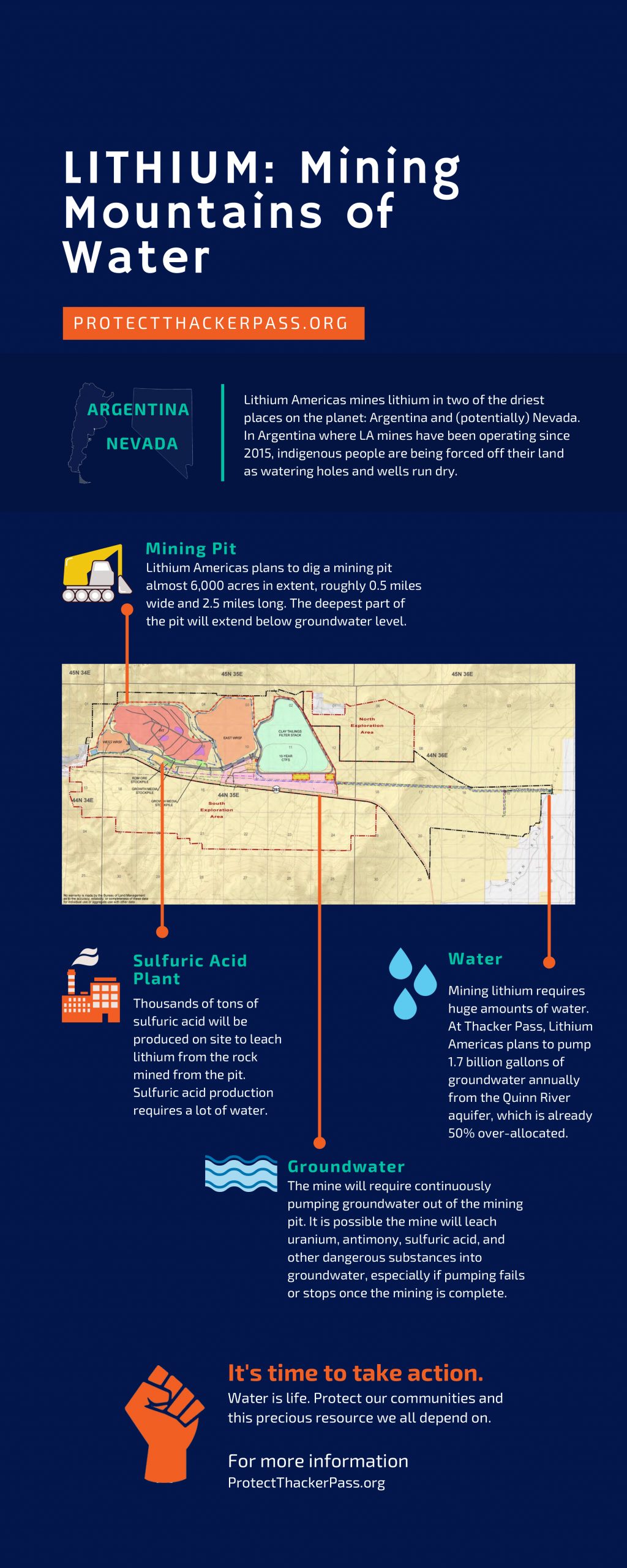

Mining in the Great Basin

The skyrocketing demand for lithium, one of the minerals needed for the production of electric cars, is based on the misperception that green technology helps the planet. Yet, as Argentine professor of thermodynamics and lithium mining expert Dr. Daniel Galli said at a scientific meeting, lithium mining is “really mining mountains of water.” Lithium Americas plans to pump massive amounts of water—up to 1.7 billion gallons (5,200 acre feet) annually—from an aquifer in the Quinn River Valley in Nevada’s Great Basin, the largest desert in the United States.

Thacker Pass, the site of the proposed 1.3 billion dollar open-pit lithium mine, would pump 1,200 acre feet more water per year than Peabody Energy Corporation extracted from the Navajo aquifer. Yet, the Quinn River aquifer is already over-allocated by fifty percent, and more than 10 billion gallons (30,000 acre feet) per year. Nevada is one of the driest states in the nation, and Thacker Pass is only the first of many proposed lithium mines in the state. Multiple active placer claims (7,996) have been located in 18 different hydrographic basins.

Deceit about water fuels these mines. Lithium Americas’ environmental impact assessment is grossly inaccurate, according to hydrologist Dr. Erick Powell. By classifying year-round creeks as “ephemeral” and underreporting the flow rate of 14 springs, Lithium Americas is claiming there is less water in the area than there actually is. This masks the real effects the mine would have—drying up hundreds of square miles of land, drawing down the groundwater level, sucking water from neighboring aquifers—all while claiming its operations would have no effect.

Peabody Energy Corporation’s impact assessment similarly misrepresented how their withdrawals would harm the Navajo aquifer. Peabody Energy used a flawed method to measure the withdrawals, according to former National Science Research Fellow Daniel Higgins. Now Navajo Nation wells require drilling down 2,000–3,000 feet, and the water is depressurized and slow to flow to the surface.

Thacker Pass lithium mine would pump groundwater at a disturbing rate, up to 3,250 gallons per minute. Once used, wastewater would contaminate local groundwater with dangerous heavy metals, including a “plume” of antimony that would last at least 300 years. Lithium Americas plans to dig the mine deeper than the groundwater level and keep it dry by continuously pumping water out, but when the pumping stops, groundwater would seep back in, picking up the toxins.

It hurts me to think about this. I imagine water being rapidly extracted from my own body, my bloodstream poisoned. The best tasting water rises to the surface when it is ready, after gestating as long as it likes in the dark Earth. Springs are sacred. When I feel welcome, I place my lips on the earthy surface and fill my mouth with their sweet flavor and vibrant texture.

Mining in the Atacama Desert

Thirteen thousand feet above sea level, the indigenous Atacamas people live in the Atacama Desert, the most arid desert in the world and the driest place on Earth. For millennia, they have used their scarce supply of water and sparse terrain carefully. Their laws and spirituality have always been intertwined with the health and well-being of the land and water. Living in mud-brick homes, pack animals, llama and alpaca, provide them with meat, hide, and wool.

But lithium lies beneath their ancestral land. Since 1980, mining companies have made billions in the Salar de Atacama region in Chile, where lithium mining now consumes sixty-five percent of the water. Some local communities need to have water driven in, and other villagers have been forced to abandon their settlements. There is no longer enough water to graze their animals. Beautiful lagoons hundreds of flamingos call home have gone dry. The birds have disappeared, and the ground is hard and cracked.

In addition to the Thacker Pass mine proposal, Lithium Americas has a mine in the Atacama Desert, a joint Canadian-Chilean venture named Minera Exar in the Cauchari-Olaroz basin in Jujuy, Argentina. Digging for lithium began in Jujuy in 2015, and there is already irreversible damage, according to a 2018 hydrology report. Watering holes have gone dry, and indigenous leaders are scared that soon there will be nothing left.

Even more water is needed to mine the traces of lithium found in brine than in an open-pit mine. At the Sales de Jujuy plant, the wells pump at a rate of more than two million gallons per day, even though this region receives less than four inches of rain a year. Pumping water from brine aquifers decreases the amount of fresh groundwater. Freshwater refills the spaces emptied by brine pumping and is irreversibly mixed with brine and salinized.

The Sanctity of Water

As a river guide, I live close to water. Swallowed by its wild beauty, I am restored to a healthier existence. Far from roads, cars, and cities, I watch water swirl around rocks or ripple over sand. I merge with its generous flow, floating through mountains, forest, or canyon. Rivers teach me how to listen to the currents—whether they cascade in a playful bubble, swell in a loud rush, or ebb in a gentle silence—for clues about what lies ahead.

The indigenous Atacamas peoples understand that water is sacred and have purposefully protected it for centuries. Rather than looking at how nature can be used, our culture needs to emulate the Atacamas peoples and develop the capacity to consider its obligations around water. Instead of electric cars, what we need is an ethical approach to our relationship with the land. Honoring the rights of water, species, and ecosystems is the foundation of a sustainable society. Decisions can be made based on knowledge of the land, weather patterns, and messages from nature.

For millennia, indigenous peoples have perceived water, animals, and mountains as sentient. If humans today could recognize their intelligence, perhaps they would understand that underground reservoirs have a value and purpose, beyond humans. When I enter a cave, I am walking into a living being. My eyes adjust to the dark. Pressing my hand against the wall, I steady myself on the uneven ground, hidden by varying amounts of water. Pausing, I listen to a soft dripping noise, echoing like a heartbeat as dew slides off the rocks. I can almost hear the cave breathing.

The life-giving waters of aquifers keep everything alive, but live unseen under the ground. As a soul guide, I invite people to be nourished by the visions of their dreams, a parallel world that is also seemingly invisible. Our dominant culture dismisses the value of these perceptions, just as it usurps water by disregarding natural cycles. Yet to create a sustainable world, humans need to be able to listen to nature and their dreams. The depths of our souls are inextricably linked to the ancient waters that flow underground. Dreams arise like springs from an aquifer, seeding our visionary potential, expanding our consciousness, and revealing other ways to live, radically different than empire.

Water Bearers

I set my backpack down on a high sandstone cliff overlooking a large watering hole. Ten feet below the hole, the red rock canyon drops into a much larger pool. My friend hikes down to it, filling her cookpot with water. She balances it atop her head on the way up, moving her hips to keep the pot steady. Arriving back, she pours the water into the smaller hole from which we drink and returns to the large pool to gather more.

Women in all societies have carried water throughout history. In many rural communities, they still spend much of the day gathering it. Sherri Mitchell of the Penobscot Nation calls women “the water bearers of the Universe.” The cycles in a woman’s body move in relation with the Earth’s tides, guiding them to nourish and protect the waters of Earth. We all need to become water bearers now.

Indigenous peoples, who have always been the Earth’s greatest defenders, protect eighty percent of global diversity, even though they comprise less than five percent of the world’s population. They understand water is sacred, and the world’s groundwater systems must be defended. For six years, indigenous peoples have been fighting to prevent lithium mining in the Salinas Grandes salt flats, in Jujuy, Argentina. Five hundred indigenous people camped on the land with signs: “No to lithium. Yes, to water and life in our territories.”

In February 2021, President Biden signed executive orders supporting the domestic mining of “critical” minerals like lithium, but two lawsuits, one by five Nevada-based conservation groups, have been filed against the Bureau of Land Management for approving the Thacker Pass lithium mine. Environmentalists Max Wilbert and Will Falk are organizing a protest to protect Thacker Pass. Local residents, including Northern Paiute and Western Shoshone peoples, are speaking out, fighting to protect their land and water.

We can see when a river runs dry, but most people are not aware of the invisible, slow-burning disaster happening under the ground. Some say those who oppose lithium mining should give up cell phones. If that is true, perhaps those who favor mines should give up drinking water. Protecting water needs to be at the center of any plan for a sustainable future.

The “fossil water” found in deserts should be used only in emergency, certainly not for mining. Sickened by corporate water grabbing, I support those trying to stop Thacker Pass Lithium mine and aim to join them. The aquifers there have nurtured so many for so long—eagles, pronghorn antelope, mule deer, old-growth sagebrush, hawks, falcons, sage-grouse, and Lahontan cutthroat trout. I pray these sacred wombs of the Earth can live on to nourish all of life.

For more on the issue:

![“May the truth be your armor” [Excerpts from Bright Green Lies]](https://dgrnewsservice.org/wp-content/uploads/sites/18/2021/05/BGL.jpeg)

![Will Thacker Pass, At Last, Be Still? [Dispatches from Thacker Pass]](https://dgrnewsservice.org/wp-content/uploads/sites/18/2021/05/SnowAtThackerPass-980x735-1.jpg)