by DGR News Service | Apr 21, 2023 | ANALYSIS, Biodiversity & Habitat Destruction, Climate Change, Mining & Drilling

Editor’s Note: Mainstream environmental organizations propose electric vehicles (EVs) as a solution to every environmental crisis. It is not only untrue, but a delusion. It does not matter to the hundreds of lives lost whether they were killed for extraction of fossil fuel for traditional internal combustion (IC) cars, or for extraction of materials necessary for manufacturing EVs. What matters is that they are dead, never to come back, and that they died so a portion of humans could have convenient mobility. DGR is organizing to oppose car culture: both IC and EVs.

By Benja Weller

I am a rich white man in the richest time, in one of the richest countries in the world (…)

Equality does not exist. You yourself are the only thing that is taken into account.

If people realized that, we’d all have a lot more fun.

ZDF series Exit, 2022, financial manager in Oslo,

who illegally traded in salmon

Wir fahr’n fahr’n fahr’n auf der Autobahn

Vor uns liegt ein weites Tal

Die Sonne scheint mit Glitzerstrahl

(We drive drive drive on the highway

Ahead of us lies a wide valley

The sun shines with a glittering beam)

Kraftwerk, Single Autobahn / Morgenspaziergang, 1974

Driving a car is a convenient thing, especially if you live in the countryside. For the first time in my life I drive a car regularly, after 27 years of being “carless”, since it was left to me as a passenger. It’s a small Suzuki Celerio, which I call Celery, and fortunately it doesn’t consume much. Nevertheless, I feel guilty because I know how disturbing the engine noise and exhaust fumes are for all living creatures when I press the gas pedal.

So far, I have managed well by train, bus and bicycle and have saved a lot of money. As a photographer, I used to take the train, then a taxi to my final destination in the village and got to my appointments on time. Today, setting off spontaneously and driving into the unknown feels luxurious.

However, my new sense of freedom is in stark contrast to my understanding of an intact environment: clean air, pedestrians and bicyclists are our role models, children can play safely outside. A naive utopia? According to the advertising images of the car industry, it seems as if electric cars are the long-awaited solution: A meadow with wind turbines painted on an electric car makes you think everything will be fine.

“Naturally by it’s very nature.” says the writing on an EV of the German Post, Neunkirchen, Siegerland (Photo by Benja Weller)

In Germany, the car culture (or rather the car cult) rules over our lives so much that not even a speed limit on highways can be achieved. The car industry has been receiving subsidies from the government for decades and journalists are ridiculed when they write about subsidies for cargo bikes.

Right now, this industry is getting a green makeover: quiet electric cars that don’t emit bad air and are “CO2 neutral” are supposed to drive us and subsequent generations into an environmentally friendly, economically strong future. On Feb. 15, 2023, the green party Die Grünen published in its blog that the European Union will phase out the internal combustion engine by 2035: “With the approval of the EU Parliament on Feb. 14, 2023, the transformation of the European automotive industry will receive a reliable framework. All major car manufacturers are already firmly committed to a future with battery-electric drives. The industry now has legal and planning certainty for further investment decisions, for example in setting up its own battery production. The drive turnaround toward climate-friendly vehicles will create future-proof jobs in Europe.”

That’s good news – of course for the automotive industry. All the old cars that will be replaced with new ones by 2035 will bring in more profit than old cars that will be driven until they expire. That the EU along with the car producers, are becoming environmentalists out of the blue is hard to believe, especially when you see what cars drive on German roads.

In recent years, a rather opulent trend became apparent: cars with combustion engines became huge in size and gasoline consumption increased, all in times of ecological collapse and global warming. These oversized SUVs are actually called sport-utility vehicles, even if you only drive them to get beer at the gas station. Small electric cars seem comfortable enough and have a better environmental footprint than larger SUVs. But the automotive industry is not going to let the new electromobility business go to waste that easily and is offering expensive electric SUVs: The Mercedes EQB 350 4matic, for example, which weighs 2.175 tons and has a 291-hp engine, costs €59,000 without deducting the e-car premium.

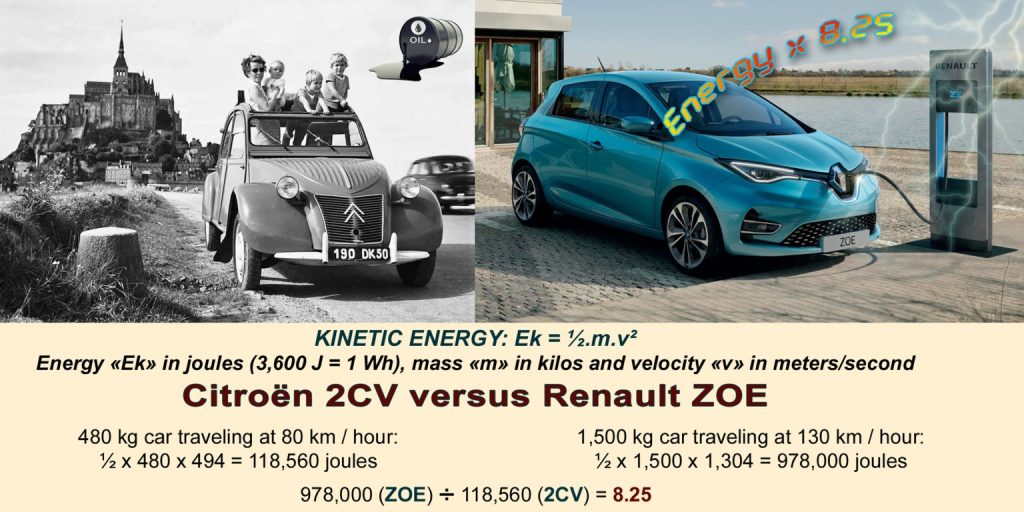

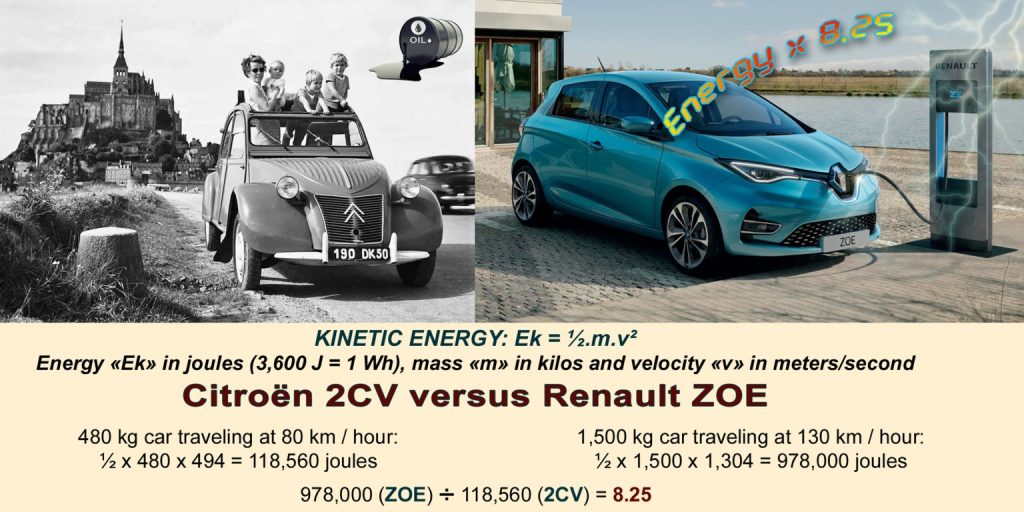

Comparing the Citroen 2CV and the Renault Zoe electric car shows that the Zoe uses about 8 times more kinetic energy. (Graph by Frederic Moreau)

If we look at all the production phases of a car and not just classify it according to its CO2 emmissions, the negative impact of the degradation of all the raw materials needed to build the car becomes visible. This is illustrated by the concept of ecological backpack, invented by Friedrich Schmidt-Bleek, former head of the Material Flows and Structural Change Department at the Wuppertal Institute for Climate, Environment and Energy. On the Wuppertal Institute’s website, one can read that “for driving a car, not only the car itself and the gasoline consumption are counted, but also proportionally, for example, the iron ore mine, the steel mill and the road network.”

“In general, mining, the processing of ores and their transport are among the causes of the most serious regional environmental problems. Each ton of metal carries an ecological backpack of many tons, which are mined as ore, contaminated and consumed as process water, and weigh in as material turnover of the various means of transport,” the Klett-Verlag points out.

Car production requires large quantities of steel, rubber, plastic, glass and rare earths. Roads and infrastructure suitable for cars and trucks must be built from concrete, metal and tar. Electric cars, even if they do not emit CO2 from the exhaust, are no exception. Added to this is the battery, for which electricity is needed that is generated at great material expense, a never-ending cycle of raw material extraction, raw material consumption and waste production.

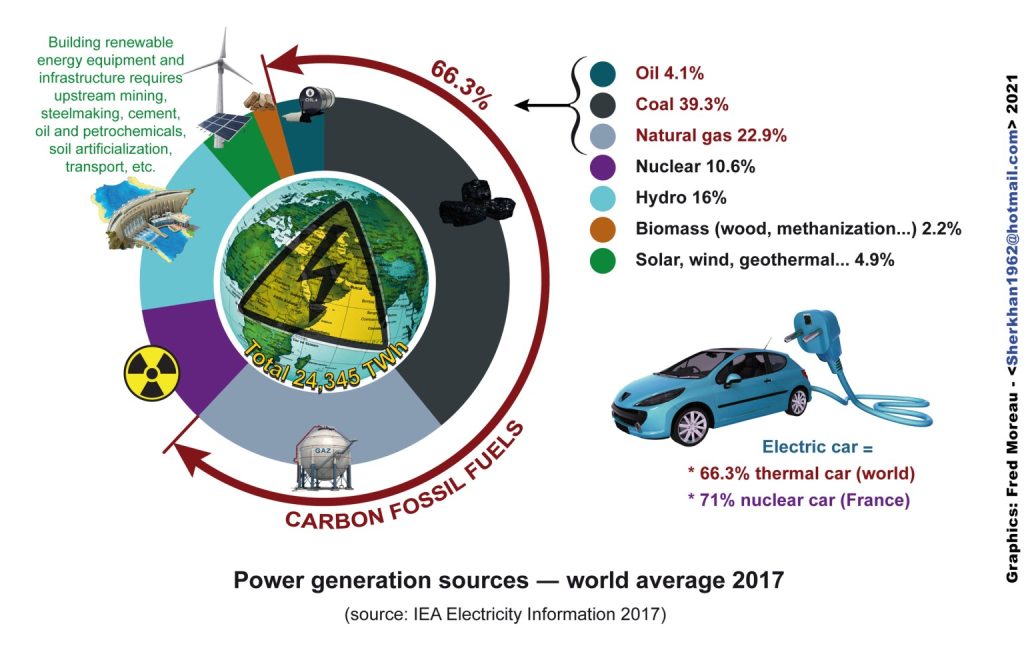

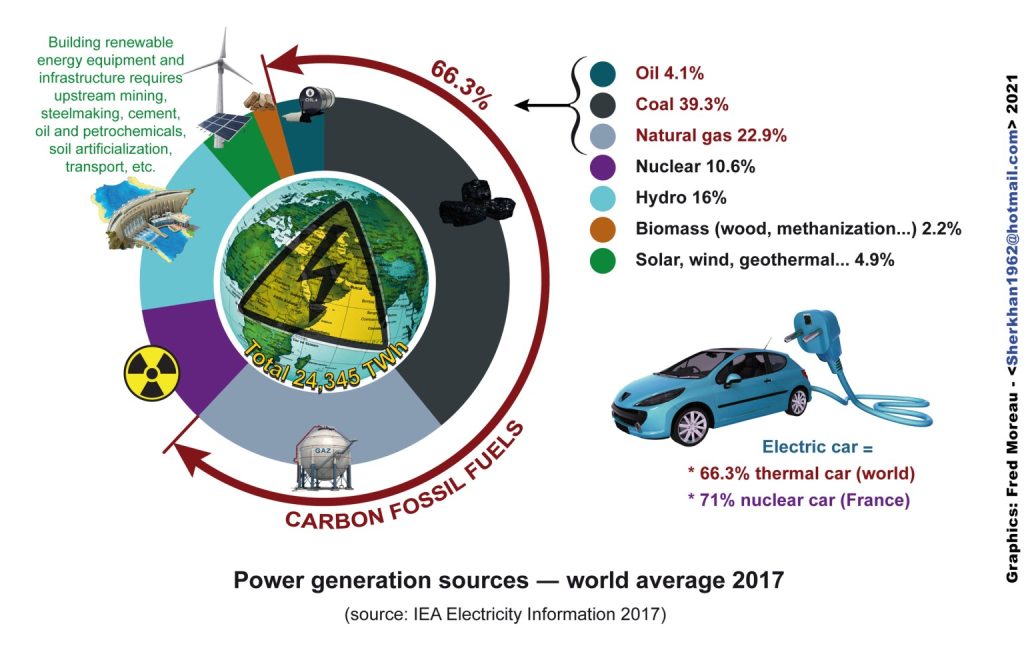

Power generation sources for electric vehicles (Graph by Frederic Moreau)

Lithium is a component of batteries needed for electric cars. For the production of these batteries and electric motors, raw materials are used “that are in any case finite, in many cases already available today with limited reserves, and whose extraction is very often associated with environmental destruction, child labor and overexploitation,” as Winfried Wolf writes in his book Mit dem Elektroauto in die Sackgasse, Warum E-Mobilität den Klimawandel beschleunigt (With the electric vehicle into the impasse, why e-mobility hastens climate change).

What happens behind the scenes of electric mobility, which is touted as “green,” can be seen in the U.S. campaign Protect Thacker Pass. In northern Nevada, a state in the western U.S., resistance is stirring against the construction of an open-pit mine by the Canadian company Lithium Americas, where lithium is to be mined. Here, a small group of activists, indigenous peoples and local residents have united to raise awareness of the destructive effects of lithium mining for electric car batteries and to prevent the lithium mine in the long term with the Protect Thacker Pass campaign.

Thacker Pass is a desert area (also called Peehee muh’huh in the native language of the Northern Paiute) that was originally home to the indigenous peoples of the Northern Paiute, Western Shoshone, and Winnemuca Tribes. The barren landscape is still home to some 300 species of animals and plants, including the endangered Kings River pyrg freshwater snail, jack rabbit, coyote, bighorn sheep, golden eagle, sage grouse, and pronghorn, and is home to large areas of sage brush on which the sage grouse feeds 70-75% of the time, and the endangered Crosby’s buckwheat.

For Lithium Americas, Thacker Pass is “one of the largest known lithium resources in the United States.” The Open-pit mining would break ground on a cultural memorial commemorating two massacres perpetrated against indigenous peoples in the 19th century and before. Evidence of a rich historical heritage is brought there by adjacent caves with burial sites, finds of obsidian processing, and 15,000-year-old petroglyphs. For generations, this site has been used by the Northern Paiute and Western Shoshone tribes for ceremonies, traditional gathering and hunting, and educating young Native people. Now it appears that the history of the colonization of Thacker Pass is repeating itself.

According to research by environmental activists, the lithium mine would lower the water table by 10 meters in one of the driest areas in the U.S., as it is expected to use 6.4 billion gallons of water per year for the next 40 years. This would be certain death for the Kings River pyrg freshwater snail. Mining one ton of lithium generally consumes 1.9 million liters of water at a time when there is a global water shortage.

The mine would discharge uranium, antimony, sulfuric acid and other hazardous substances into the groundwater. This would be a major threat to animal and plant species and also to the local population. Their CO2 emissions would come up to more than 150,000 tons per year, about 2.3 tons of CO2 for every ton of lithium produced. So much for CO2-neutral production! Thanks to a multi-billion dollar advertising industry, mining projects are promoted as sustainable with clever phrases like “clean energy” and “green technology”.

About half of the local indigenous inhabitants are against the lithium mine. The other half are in favor of the project, hoping for a way out of financial hardship through better job opportunities. Lithium Americas’ announcement that it will bring an economic boost to the region sounds promising when you look at the job market there. But there’s no guarantee that working conditions will be fair and jobs will be payed well. According to Derrick Jensen, jobs in the mining industry are highly exploitative and comparable to conditions in slavery.

Oro Verde, The Tropical Forest Foundation, explains: “With the arrival of mining activities, local social structures are also changing: medium-term social consequences include alcohol and drug problems in the mining regions, rape and prostitution, as well as school dropouts and a shift in career choices among the younger generation. Traditional professions or (subsistence) agriculture are no longer of interest to young people. Young men in particular smell big money in the mines, so school dropouts near mines are also very common.”

Seemingly paradoxically, modern industrial culture promotes a rural exodus, which in turn serves as an argument for the construction of mines that harm the environment and people. Indigenous peoples have known for millennia how to be locally self-sufficient and feed their families independently of food imports. This autonomy is being repeatedly snatched away from them.

Erik Molvar, wildlife biologist and chair of the Western Watersheds Project, says of the negative impacts of lithium mining in Thacker Pass that “We have a responsibility as a society to avoid wreaking ecological havoc as we transition to renewable technologies. If we exacerbate the biodiversity crisis in a sloppy rush to solve the climate crisis, we risk turning the Earth into a barren, lifeless ball that can no longer sustain our own species, let alone the complex and delicate web of other plants and animals with which we share this planet.”

We share this planet with nonhuman animal athletes: The jack rabbit has a size of about 50cm (1.6 feet), can reach a speed of up to 60 km/h (37mph) and jump up to six meters (19.7 feet) high from a standing position. In the home of the jack rabbit, 25% of the world’s lithium deposits are about to be mined. To produce one ton of lithium, between 110 and 500 tons of earth have to be moved per day. Since lithium is only present in the clay rock in a proportion of 0.2-0.9%, it is dissolved out of the clay rock with the help of sulfuric acid.

According to the Environmental Impact Statement from the Thacker Pass Mine (EIS), approximately 75 trucks are expected to transport the required sulfur each day to convert it to sulfuric acid in a production facility built on site. This means that 5800 tons of sulfuric acid would be left as toxic waste per day. Sulfur is a waste product of the oil industry. How convenient, then, that the oil industry can simply continue to do “business as usual.”

Nevada Lithium, another company that operates lithium mines in Nevada states: “Electric vehicles (EVs) are here. The production of lithium for the batteries they use is one of the newest and most important industries in the world. China currently dominates the market, and the rest of the world, including the U.S., is now responding to secure its lithium supply.” The demand for lithium is causing its prices to skyrocket: Since the demand for lithium for the new technologies is high and the profit margin is 46% according to Spiegel, every land available will be used to mine lithium.

Lithium production worldwide would have to increase by 400% to meet the growing demand. With this insane growth rate as a goal, Lithium Americas has begun initial construction at Thacker Pass on March 02, 2023. But environmentalists are not giving up, they are holding meetings, educating people about the destructive effects of lithium mining, and taking legal action against the construction of the mine.

Let’s take a look at the production of German electric cars.

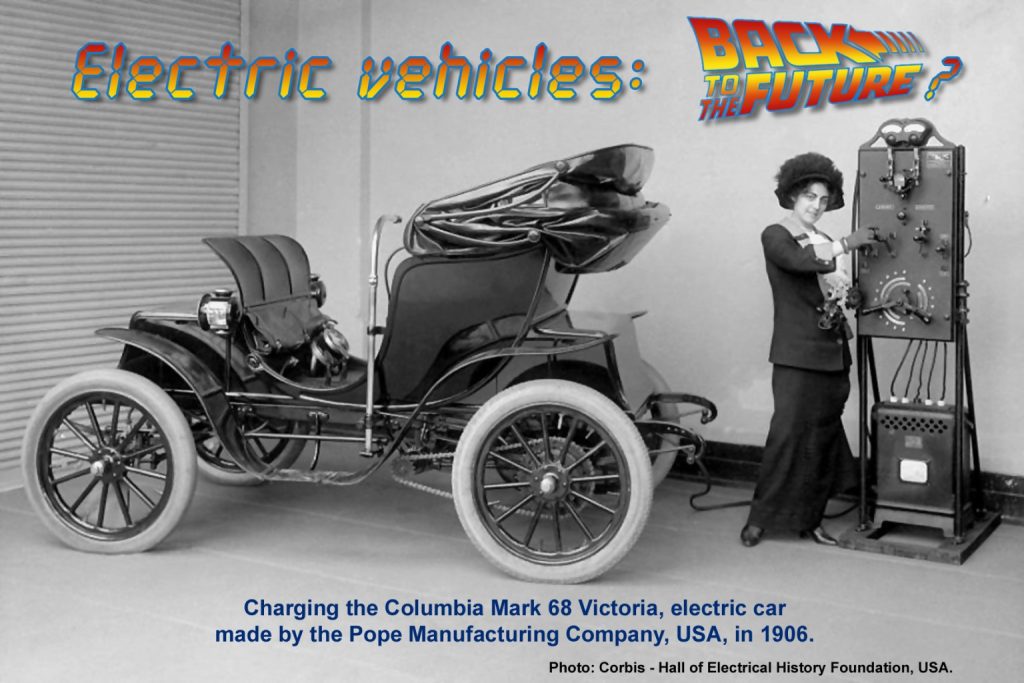

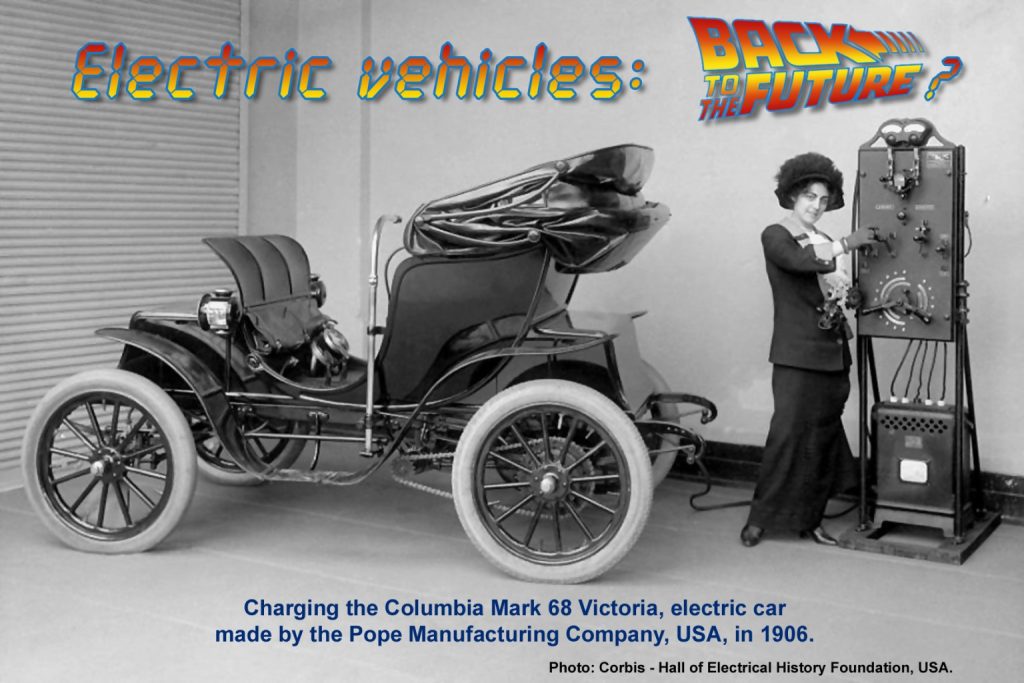

Meanwhile, this is the third attempt to bring electric cars to the market in Germany. In the early 20th century, Henry Ford’s internal combustion engine cars replaced electric-powered cars on the roads.

Graph by Frederic Moreau

“In fact, three decades ago, there were similar debates about the electric car as today. In 1991, various models of electric vehicles were produced in Germany and Switzerland,” writes Winfried Wolf. “At that time, it was firmly assumed that the leading car companies would enter into the construction of electric cars on a large scale.”

He goes on to write about a four-year test on the island of Rügen that tested 60 electric cars, including models by VW, Opel, BMW and Daimler-Benz passenger cars from 1992 to 1996. The cost was 60 million Deutsche Mark. The Institute for Energy and Environmental Research (IFEU) in Heidelberg, commissioned by the Federal Ministry of Research, concluded that electric cars consume between 50 percent (frequent drivers) and 400 percent more primary energy per kilometer than comparable cars with internal combustion engines. The test report states that the Federal Environment Agency (UBA) in Berlin also sees its rejection of the electric car strategy confirmed.

There is no talk of these test results in times of our current economic crisis: also German landscapes and its water bodies must make way for a “green” economic policy. We can see the destructive effects of electric car production centers in the example of Grünheide, a town in Brandenburg 30 km from Berlin.

Manu Hoyer, together with other environmentalists in the Grünheide Citizens’ Initiative, rebel against the man who wants to discover life on other planets because the Earth is not enough: Elon Musk. She explains in an article by Frank Brunner in the magazine Natur how Tesla proceeded to build the Gigafactory Berlin-Brandenburg with supposedly 12,000 employees: First, they deforested before there was even a permit, and when it was clear that the electric car factory would be built, Tesla planted new little trees elsewhere as compensation.

The neutral word “deforestation” does not explain the cruel process behind it: Wildlife have their habitat in trees, shrubs and in burrows deep in the earth. In the Natur article, Manu Hoyer recalls that the sky darkened “with ravens waiting to devour the dead animals among the felled trees.”

In the book The Day the World Stops Shopping, J.B. MacKinnon describes, based on a study of clearing in Australia, that the scientific consensus is that the majority, and in some cases all, of the individuals living at a site will die when the vegetation disappears.

It doesn’t sound pretty, but it’s the reality when you read that animals are “crushed, impaled, mauled or buried alive, among other things. They suffer internal bleeding, broken bones or flee into the street where they are run over.” Many would stubbornly resist giving up their habitat.

In this, they are like humans. Nobody gives up her piece of land or his house without a fight when it is taken away from him; animals and humans both love the good life. But the conditions of wild animals play no role in our civil society, they should be available anytime to be exlpoited for our needs.

In order not to incite nature lovers, legal regulations are supposed to lull them into the belief that what is happening here is morally right. Behind this is a calculus by the large corporations, which in return for symbolic gestures can continue the terror against nature blamelessly.

In December 2022, Tesla was granted permission to buy another 100 hectares of forest to expand the car factory site to 400 hectares. The entire site had long been available for new industrial projects, although it is also a drinking water protection area. The Gigafactory uses 1.4 million cubic meters of water annually in a federate state plagued by drought.

Manu Hoyer tells Deutschlandfunk radio that dangerous chemicals are said to have leaked only recently and contaminated firefighting water seeped into the groundwater during a fire last fall. Another environmentalist, Steffen Schorcht, who studied biocybernetics and medical technology, criticizes local politicians for their lethargy in the face of environmental destruction. He sees no other way to fight back than to join forces with other citizens and international organizations outside of politics.

The beneficiaries are not the people who make up the bulk of the population. Tesla cars go to drivers who are happy to spend 57,000€ for a car with a maximum of 535 horsepower.

I can still remember how, as a child, I used to drive with my parents on vacation to the south of France, Italy or Austria in the Citroën 2CV model (two horsepower). Such a car trip was more adventure than luxury, but the experiences during the simple camping vacations in Europe’s nature have remained formative childhood memories.

The author sitting on the hood of a Citroën 2CV in Tuscany, Italy, 1989 (Photo: private)

Today, we have to go a big step further than just living a “simple life” individually. The car industry is pressing the gas pedal, taking the steering wheel out of our hands and driving us into the ditch. It’s time to get out, move our feet and stand up against the car industry.

The BDI, Federation of German Industries, writes in its 2017 position paper on the interlocking of raw materials and trade policy in relation to the technologies of the future that without raw materials there would be no digitalization, no Industry 4.0 and no electromobility. This statement confirms that our western lifestyle can only be financed through the destruction of the last natural habitats on Earth.

The mining of lithium and other so-called “raw materials” for new technologies is related to our culture, which imposes a techno-dystopia on the functioning organism Earth, that nullifies all biological facts. If we want to save the world, it seems to me, we should not become lobbyists for the electric car industry. Rather, we should organize collectively, learn from indigenous peoples, defend the water, the air, the soil, the plants, the wildlife, and everyone we love. The brave environmentalists in Grünheide and Thacker Pass are showing us how.

Homo sapiens have done well without cars for 200,000 years and will continue to do so. All we need is the confidence that our feet will carry us.

Wir fahr’n fahr’n fahr’n auf der Autobahn, Kraftwerk buzzed at the time

as an ode to driving a car

I glide over the asphalt to the points in lonely nature,

give myself a time-out from the confines of the small town

Bus schedules in German villages are an old joke

Buy me a Mercedes Benz, cried Janis Joplin devotedly,

without an expensive car, life is only half as valuable

Car-free Sundays during the oil crisis as a nostalgic anecdote

Driving means freedom and compulsion at the same time, asphalt is forced upon topsoil

with millions of living beings per tablespoon of earth

You must go everywhere: To the supermarket, to school, to work, to the store,

to the club, to friends, and to the trail park

Be yourself! they tell you, but without a car you’re not yourself,

on foot with a lower social status than on wheels

The speed limit dismissed each time, which party stands for the wild nature,

our ancient living room? Don’t vote for them, they deceive too

Believe yourself! they say, but what else can you believe, grown up believing

that this civilization is the only right one

Drive, drive, drive and the airstream flies in your hair –

Freedom, the one moment you have left

Featured image: A view of Thacker Pass by Max Wilbert

by DGR News Service | Apr 14, 2023 | ANALYSIS, Colonialism & Conquest, The Problem: Civilization, Toxification

Editor’s Note: The civilization has destroyed many places in the name of progress, which they call ‘sacrifice zones.’ The following piece discusses different instances of destruction from recent history, and how the current economy has actively profited from those destructions. The views expressed in the article are of the author. DGR does not necessarily agree with all of the opinions expressed.

By Mankh

Considering the destruction caused by extractive mining and wars, the global corporate empire society sure seems like one huge controlled demolition. Before getting to the topic of Electric Vehicles (EVs) and specifically Thacker Pass aka Peehee Mu’huh, some examples and explanation of the context of controlled demolition.

Currently in Ukraine, various governments/investors are making bank on both ends of the stick: from the weapons manufacturers destruction end AND the BlackRock, Inc. (an American multi-national investment company) et al reconstruction end. A December 2022 CNBC headline spilled the beans: “Zelenskyy, BlackRock CEO Fink agree to coordinate Ukraine investment” and more recently: “The estimated cost of Ukraine’s reconstruction and recovery bill has grown to $411 billion.” — while US infrastructure crumbles. A key aspect of the reconstruction is multinational agri-businesses salivating over Ukraine’s rich soil, something rarely mentioned in umpteen war analyses.

Speaking of crumbling infrastructure, the derailed train and subsequent deliberate explosions of toxic chemicals in Palestine, Ohio (which includes rivers), has created an environmental disaster; another controlled demolition because lack of care for railroad maintenance and extra care for dollars helped create the accident waiting to happen.

From an article by Tish O’Dell and Chad Nicholson:

“Three days after the derailment, on Feb. 6, we watched as Ohio Gov. Mike DeWine, in consultation with Norfolk Southern representatives, greenlighted a plan to blow holes in five of the cars containing toxic chemicals, which would lead to a ‘controlled release,’ and residents in nearby communities were ordered to evacuate. … By Feb. 7, according to a Norfolk Southern service alert, trains were running through East Palestine again. As thousands of dead fish floated in local waterways, as nearby residents were reporting sickness and dying pets, as untold long-term health and environmental problems lurked in the hazy future, the railroad chugged back to business as usual.”

Also sadly, “East Palestine Soil Contains Dioxin Levels Hundreds of Times Over Cancer Risk Threshold”

The broader issue to consider is this: controlled demolition requires careful preparation or deliberate lack there of—and then with the virtual flick of a switch, it happens . . . like dominoes. And a ‘new reality’ is created. What quickly followed the 9-11 attacks was the Global War Of Terror, later determined to have been riddled with lies.

After Covid-19 began, there were lockdowns and a slew of enforced restrictions, many of which were later deemed unwarranted. The world changed in a flash, as did the economy, with many small and some larger businesses going bust, as the elite rich got richer. Yet whatever one’s opinion about all that, the message from the natural world was quiet and clear: rivers and skies cleared up! . . . showing that healing can happen quickly―if we drastically curtail the business as usual of industrial capitalism.

After Ukraine re-began with Russia’s attacks (because the situation ‘began’ in 2014 with the Maidan/neo-Nazi coup overthrowing elected Ukrainian President Viktor Yanukovych) . . . economic sanctions, global economic shake-ups-and-downs, nuclear saber rattling, and more, including the above mentioned agri-business ploy, which, by the way, is also global, as, for example, Bill Gates is “the largest landowner in the U.S.,” owning “270,000 acres spread across 18 different states.”

A Twitter post on March 20, 2023, by esteemed journalist and filmmaker John Pilger, succinctly sums up the media-military-complex modus operandi:

And though not as visibly dramatic, preparations for controlled demolition are happening again with the deliberate push for EVs (Electric Vehicles). For example, in New York, November 2022:

“Governor Kathy Hochul signed legislation that will advance clean transportation efforts by removing barriers to the installation of electric vehicle charging stations on private property.”

&

“The Charge NY initiative offers electric car buyers the Drive Clean Rebate of up to $2,000 for new car purchases or leases. Combine that with a Federal Tax Credit of up to $7,500, and it’s an opportunity you wouldn’t want to miss. If you are a New York State resident looking for a new car, it’s a great time to buy or lease a plug-in hybrid or battery-powered car that qualifies for the Drive Clean Rebate.”

As any reader of Deep Green Resistance News Service and those following or participating in the efforts to Protect Thacker Pass knows, “clean” is false advertising and you would want to resist the opportunity. In the broad case of EVs, we, as human beings and as consumers have choices that can affect or re-direct the trajectory of this huge deliberate push for EVs, which is a kind of heating up of boiled frogs controlled demolition . . . because if not stopped, suddenly EVs will dominate the roads and landscapes, while sacred habitats and Native lands are destroyed.

As lawyer and Protect Thacker Pass co-founder Will Falk has alluded to in various interviews and videos, many aspects of the legal system are rigged in favor of government and corporate control of mining; this is a form of control with the goal of demolition of habitat and wildlife, too-often along with desecration of Native lands for profit.

I don’t have the answers for how to stop such control freak factors, but at least recognizing that there are various preparations so that a demolition ‘goes smoothly’ will help each person/group/organization find a best way to participate so as to help prevent specific preparations and perhaps prevent the controlled demolition of Thacker Pass aka Peehee Mu’huh, as well as other sacred site hot spots.

The natural world of plants also has an array of unseen or barely visible preparations until . . . a flower buds then blooms or fruit ripens; let’s call that process a controlled creation or the unfolding of innate potential, as with a seed. This is what those who care about the Earth work hard to defend, protect, and preserve—the natural cycles.

Further demolition examples

In 2017, investigative journalist, author and filmmaker Greg Palast reported:

“…an eyewitness with devastating new information about the Caspian Sea oil-rig blow-out which BP had concealed from government and the industry.

The witness, whose story is backed up by rig workers who were evacuated from BP’s Caspian platform, said that had BP revealed the full story as required by industry practice, the eleven Gulf of Mexico workers ‘could have had a chance’ of survival. But BP’s insistence on using methods proven faulty sealed their fate.

One cause of the blow-outs was the same in both cases: the use of a money-saving technique, plugging holes with ‘quick-dry’ cement. By hiding the disastrous failure of its penny-pinching cement process in 2008, BP was able to continue to use the dangerous methods in the Gulf of Mexico, causing the worst oil spill in U.S. history.”

As with East Palestine and umpteen other so-called disasters, cutting corners for profit is too-often a factor with controlled demolitions.

“Disasters like these keep happening because the system — the train — keeps rolling, exactly as it was designed to, foisting the consequences onto communities and their environments and hoarding the spoils for the economic elites, while government regulatory agencies issue permits and legalize it all.

“Since this country’s founding, our system of government has placed profits and property interests over people and planet. The derailment in East Palestine illustrates this clearly. For over 150 years, railroad workers have been telling employers like Norfolk Southern and the government that their working conditions are deplorable and dangerous.

“With deregulation of the industry in the 1980s, which included Wall Street mergers and ’short term profit imperatives,’ trains have been getting longer and longer while the number of train workers gets smaller and smaller.”

In Cobalt Red: How the Blood of the Congo Powers Our Lives, Siddharth Kara writes:

“Villages along the road are coated with airborne debris. There are no flowers to be found. No birds in the sky. No placid streams. No pleasant breezes. The ornaments of nature are gone. All color seems pale and unformed. Only the fragments of life remain. This is Lualaba Province, where cobalt is king.”

Same story again with this headline:

“‘The trees were all gone’: Indonesia’s nickel mines reveal the dark side of our electric future”

To consider these areas as sacrifice zones is a form of mental trickery because it allows people to think that, overall, things are OK, a few bad apples but things are OK in the big apple tree picture. But the other perspective is that things are not OK because continuing to destroy habitats, pollute rivers and air has a cumulative effect. Out of sight, out of mind is no longer an excuse because even with Internet and book censorship, you can often find true information—with a bit of effort.

At Thacker Pass, Lithium Americas’ attempt to destroy the habitat and Native lands for lithium for EVs and other gadgets represents a watershed moment in the global and local greenwashing attempt to revolutionize the extractive energy economy. But the problem with that is, as the word suggests, such ‘revolutions’ wind up back where they started in circular fashion, yet only with a ‘new’ look.

The east coast of Turtle Island is riddled with the aftereffects of the so-called revolution of 1776: New York, New Jersey, New England, New Hampshire, New Haven, New London, New Bedford . . . and on it goes, out to New Mexico and elsewhere. Such ‘newness’ has a track record of destruction and enforced relocation of Native Peoples, and that’s some of what’s on the proverbial table at Thacker Pass.

Shift the narrative . . . dis-invest . . . donate $s . . . employ some monkey-wrenches . . . organize, defend, protest, write something, talk . . . think about a specific area of the in the works controlled demolition that you feel you could literally help thwart. Find a way to do something so as to help prevent yet another control freak demolition. Find a way to do something to preserve “the ornaments of nature” and the lifestyles of those who care for them.

Mankh (Walter E. Harris III) is a verbiage experiencer, in other words, he’s into etymology, writes about his experiences and to encourage people to learn from direct experiences, not just head knowledge; you know, actions and feelings speak louder than words. He’s also a publisher and enjoys gardening, talking, listening, looking… His recent book is Moving Through The Empty Gate Forest: inside looking out. Find out more at his website: www.allbook-books.com

Photo by Valeriy Kryukov on Unsplash

by DGR News Service | Dec 16, 2022 | ANALYSIS, Mining & Drilling, Worker Exploitation

Editor’s note: Mainstream environmentalists have been demanding that countries across the world declare a “climate emergency.” But what does a climate emergency mean? What will the consequences be? Is there a possibility that it will be more detrimental to the environment? In this piece, Elisabeth Robson argues how declaring a climate emergency can be worse for the environment.

By Elisabeth Robson/Protect Thacker Pass

“Climate emergency”. We hear these words regularly these days, whenever there is a wild fire, a flood, or an extreme weather event of any kind. We hear these words at the annual Conference of Parties (COPs) on climate change held by the United Nations Framework Convention on Climate Change (UNFCCC), including at the COP27 meeting happening right now in Egypt. And we hear these words regularly from organizations petitioning the U.S. government to “declare a climate emergency”, and from Senators requesting the same.

Most recently, here in the U.S., we heard these words on October 4, 2022 when a group of US Senators led by Senator Jeff Merkley (D-OR) urged President Biden to “build on the inflation reduction act” and “declare a climate emergency”, writing: “Declaring a climate emergency could unlock the broad powers of the International Emergency Economic Powers Act and the Stafford Act*, allowing you to immediately pursue an array of regulatory and administrative actions to slash emissions, protect public health, support national and energy security, and improve our air and water quality.”

The requests by these Senators include two related specifically to electric vehicles:

* Maximize the adoption of electric vehicles, push states to reduce their transportation-related greenhouse gas emissions, and support the electrification of our mass transit;

* Transition the Department of Defense non-tactical vehicle fleet to electric and zero-emission vehicles, install solar panels on military housing, and take other aggressive steps to decrease its environmental impact.

The Senators continue, “The climate crisis is one of the biggest emergencies that our country has ever faced and time is running out. We need to build off the momentum from the IRA and make sure that we achieve the ambition this crisis requires, and what we have promised the world. We urge you to act boldly, declare this crisis the national emergency that it is, and embark upon significant regulatory and administrative action.”

What the Senators are requesting is that President Biden invoke the National Emergencies Act (NEA) to go above and beyond what the Biden Administration has already done to take action in this “climate emergency” by invoking the Defense Production Act and passing the Inflation Reduction Act. This is not the first time a US president has been asked to declare a climate emergency by members of Congress, but it is the most recent.

Invoking the Defense Production Act, as the administration did in April, 2022, allows the administration to support domestic mining for critical minerals (including lithium, cobalt, nickel, and manganese, which readers of this blog will recognize as essential ingredients in batteries for EVs and energy storage) with federal funding and incentives in the name of national security.

The Inflation Reduction Act, passed in August, 2022, codified into law support for domestic mining of 50 “critical minerals” to supply renewables and battery manufacturing. This law directly supports EV manufacturing by offering tax credits to car companies that use domestic supplies of metals and minerals above a certain threshold (40% to start).

We’ve already seen how the Biden Administration is using its powers under these two acts (the Defense Production Act (DPA) and the Inflation Reduction Act (IRA)) to encourage more domestic mining for “critical minerals” and the expansion of electric vehicles and charging stations. Mining companies are “celebrating”, as one journalist wrote, including Lithium Americas Corporation (LAC) whose CEO said of the IRA “We’re delighted with it.” Car companies getting support from the government to expand manufacturing, companies getting support for building out the EV charging networks, battery-making companies, and the Department of Defense must also be celebrating the infusion of government cash and the tax incentives coming their way.

The administration would have even more power to fund and incentivize mining, manufacturing, development and industry with the National Emergencies Act, or NEA. The NEA empowers the President to activate special powers during a crisis. These powers could include loan guarantees, fast tracking permits, and even suspending existing laws that protect the environment, such as the Clean Air Act, if the administration believes these laws get in the way of mining, manufacturing, and other industrial development required for addressing the climate emergency.

As described in the Brennan Center’s Guide to Emergency Powers and Their Use, in the event a national emergency is declared, such as a climate emergency, the “President may authorize an agency to guarantee loans by private institutions in order to finance products and services essential to the national defense without regard to normal procedural and substantive requirements for such loan guarantees” [emphasis added]. This authorization could occur, as stated in the NEA, “during a period of national emergency declared by Congress or the President” or “upon a determination by the President, on a nondelegable basis, that a specific guarantee is necessary to avert an industrial resource or critical technology item shortfall that would severely impair national defense capability.”

Included in the long list of requirements for a Department of Energy (DoE) loan guarantee, the loan applicant must supply “A report containing an analysis of the potential environmental impacts of the proposed project that will enable DoE to:

(i) Assess whether the proposed project will comply with all applicable environmental requirements; and

(ii) Undertake and complete any necessary reviews under the National Environmental Policy Act (NEPA) of 1969.”

In the event a climate emergency is declared, could the administration then be able to “authorize an agency to guarantee loans” to a corporation “without regard” for these requirements? If so, then a corporation could potentially skip the NEPA process currently required for a new mining project, and not bother to do an assessment about whether their project would comply with all applicable environmental requirements (e.g. requirements under the Endangered Species Act, the Clean Air Act, and the Clean Water Act).

In other words, a corporation could proceed with their project, such as a lithium mine, with little to no environmental oversight if the Administration believes the resulting products are “essential to national defense.”

We already know that the Biden Administration believes that lithium production is essential to national defense: they have explicitly stated this in their invocation of the Defense Production Act and in the Inflation Reduction Act.

Declaring a “climate emergency” would give the administration free rein to allow corporations to sidestep environmental procedures that are normally required during the process of permitting a project like a mine, resulting in more harm to the environment.

Aside from these technical details about the implications of declaring a climate emergency, we know that most organizations, including those participating in COP27 and the 1,100 organizations that signed a February 2022 letter to President Biden urging him to declare a climate emergency, are demanding actions that would further harm the environment, such as “maximiz[ing] the adoption of electric vehicles” and “transition[ing] the Department of Defense…to electric and zero-emission vehicles” as demanded in the Senators’ October 4 letter to President Biden.

While these actions may reduce some greenhouse gas emissions, neither of these actions will reduce other harms to the environment, because these actions require more extraction and more development. And neither of these actions will reduce greenhouse gas emissions at a scope large enough to solve the climate crisis. What the activists, organizations, and Senators crying out for the President to declare a climate emergency seemingly fail to understand is that the climate emergency isn’t the only emergency we face.

Industrial development, and more specifically, industrial agriculture, has caused a 70% reduction in wildlife numbers just since 1970. This is an emergency inextricably linked with and just as dire as the climate crisis, yet the Senators and organizations calling for a climate emergency don’t demand a reduction in overall industrial development, only a reduction in fossil fuels development.

Each year, 24 billion tons of topsoil are lost, due primarily to industrial agriculture practices and deforestation. In 2014, the UN estimated that if current degradation rates continue, all the world’s top soil could be gone within 60 years. This too is an emergency inextricably linked with and just as dire as the climate crisis, yet again, the Senators and organizations calling for a climate emergency don’t demand actions to rebuild and restore soil.

Industry, including the military-industrial complex, has polluted the entire planet with toxic levels of mercury, lead, PCBs, dioxins, forever chemicals such as PFAS chemicals, and micro- and nano-plastics. These toxics are in the water we drink, the food we eat, and the air we breathe—“we” being, of course, not just humans but all wildlife on the planet. Again, this is an emergency just as dire as the climate emergency.

More than 50 million gallons of wastewater contaminated with arsenic, lead, and other toxic metals flows daily from some of the most contaminated mining sites in the U.S. into groundwater, rivers, and ponds. Mining waste that is captured must be stored and/or treated indefinitely “for perhaps thousands of years,” as the Associated Press wrote memorably in a 2019 article on mining waste. Replicate this kind of mining waste pollution around the world, and obviously, this too is an emergency just as dire as the climate emergency.

There are many such emergencies. Humans, our industry, and our developments have destroyed half of the land on Earth, and one third of all Earth’s forests. 60% of all mammals on Earth are now human livestock, mostly cattle and pigs, and 70% of all birds are now farmed poultry. This along with the staggering loss of wild beings due to human development and the destruction of habitat has resulted in the sixth mass extinction of life in Earth’s history—the only one caused by us.

All of these emergencies are related to climate change, of course. The more our societies develop, the more harm we do to the natural world, including the atmosphere.

“Development” is really global technological escalation by industry to extract more materials more efficiently, destroying more of the planet in its relentless theft of “resources.” The more our societies develop, the less habitat for life is left, and the more we overshoot the ability of the Earth to sustain us and the rest of the species on Earth.

We ignore these other emergencies at our peril. Indeed, ignoring them in favor of the climate emergency often exacerbates these emergencies. When the organizations mentioned above demand increases in electric vehicles, increases in batteries, increases in renewables, and increases in climate mitigation and adaptation (building sea walls, retrofitting and improving roads and bridges, moving entire cities), what they are demanding is more development, not less, which means more harm, not less, to the natural world. For instance, we know that the materials required to supply the projected battery demand in 2035 will require 384 new mines. That’s to supply the materials just for batteries.

Ultimately, what most organizations that support declaring a climate emergency want is not to protect life on this planet, but rather, to protect this way of life: the one we’re living now, the one that’s killing the planet. These organizations believe that we can simply replace CO2-emitting fossil fuels with EVs and so-called renewables, and keep living these ecocidal lifestyles we have become accustomed to.

We know this to be true, because we can see it directly in the actions already taken by the Biden administration, actions that will dramatically increase mining in the U.S. Mining increases the destruction of the natural world, meaning MORE habitat loss, not less. Mining increases toxic pollution. Mining increases deforestation. Mining increases top soil loss. In other words, these actions will significantly worsen all the emergencies we, and all life on the planet, face.

Rather than demand governments around the world declare a “climate emergency,” we could instead demand governments around the world declare an “ecological overshoot emergency.” In place of demands to increase industry, increase mining, and build new cars and new energy infrastructure, we could instead demand governments reduce industry, end mining, help wean us completely away from cars, and dramatically reduce energy extraction, production, and consumption. In place of demands to continue a way of life that cannot possibly continue much longer, with its relentless destruction of the natural world, we could instead demand that all societies around the world center what makes life possible on this planet: flourishing and fecund natural communities, of which we could be a thriving part, rather than dominate and destroy.

Join us and help Protect Thacker Pass, or work to defend the wild places you love. We can’t save the planet by destroying the planet in the name of a “climate emergency.”

~~~

* In their October 4 letter to President Biden, the Senators mention how invoking the NEA could “unlock the broad powers of the International Emergency Economic Powers Act and the Stafford Act.” The International Emergency Economic Powers Act (IEEPA) authorizes the president to regulate international commerce after declaring a national emergency, for instance by blocking transactions with corporations based in foreign countries, or by limiting trade with those foreign countries. This would, like the IRA, incentivize building domestic supply chains and manufacturing capabilities. The Stafford Disaster Relief and Emergency Assistance Act encourages states to develop disaster preparedness plans, and provides federal assistance programs in the event of disaster. In the event of an emergency, such as a declared climate emergency, the President could direct any federal agency (e.g. FEMA) to use its resources to aid a state or local government in emergency assistance efforts, and to help states prepare for anticipated hazards. In the event of a declared climate emergency, this would unleash federal funds and other incentive programs to states to build and harden infrastructure that is vulnerable to wildfire, floods, severe storms, ocean acidification, and other effects of climate change.

Featured Image: Climate emergency – Melbourne #MarchforScience on #Earthday by Takver from Australia. Via Wikemedia Commons (CC BY 2.0)

What does it take to make an electric car?

by DGR News Service | Oct 9, 2022 | ANALYSIS

Editor’s note: Contrary to what mainstream environmental organizations assert, so-called “renewable” energy is NOT a solution to the ecological crisis we are facing. It would require a tremendous amount of energy to mine materials; transport and transform them through industrial processes like smelting; turn them into solar panels, wind turbines, batteries, vehicles, infrastructure, and industrial machinery plus installation and maintenance. This is all done using the same systems of power which is currently used for conventional fossil fuels. The resulting emissions from these process will only add to the business as usual emissions. While the wind and sun may be “renewable,” the turbines, solar panels, the raw materials that go into making them, and the lands and oceans they impact certainly are not. They require tons of carbon emissions to produce so they are not carbon free and not green. Calling them “green” is greenwashing.

The proposed mass adoption of “renewable” energy on a hitherto undreamed of scale has made the issue of energy (power) density extremely important . In its simplest terms, power density can be understood as: ‘how big does my power station have to be, in order to generate the power I want?’ The most useful metric is the land (or sea) area that will be used up. Here, we encounter the most easily understood, and the most insoluble of “renewable” energy’s problems. Compared to fossil fuel, it’s power density is very very low. Thus, they require larger areas of land to produce. This land is someone’s home, someone’s sacred site, someone’s source of food, water and air. We just don’t hear about them, because they are the wild beings, the nonhumans treated as disposables by civilization. The humans that inhabit the land are indigenous peoples who are yet to be fully assimilated into the industrial culture. Here, we can see colonialism and extractive economics come together.

The following article describes the plans for different “renewable” energy plants in California and Nevada. The article also demonstrates how the plans for big “renewables” actively reinforce the existing structures of power, with the energy companies lobbying to disincentivize decentralized and community-controlled rooftop solars in favor of big projects that are destroying the neighbors.

By Joshua Frank/Counterpunch

There is a lot of hot air blowing around the West these days, blustery claims that geothermal, wind, massive solar installations, nuclear power, along with a smattering of hydroelectric dams, will help the country achieve a much-needed reduction in climate-altering emissions. Certainly, there is money to be made off of this energy transition, and on paper, a few do appear to be far less damaging than coal-fired power plants and natural gas operations.

That’s if, of course, you ignore the toll these energy ventures have on the lands and people they exploit. Right now, not far from where I live in Southern California, solar companies are gobbling up public and private lands for future solar and wind projects.

Across the border in Nevada, desert is under threat of being developed in the name of fighting climate change. In the rich and biodiverse Dixie Valley, located in the middle of sacred Shoshone and Paiute lands, a massive geothermal project called the Dixie Meadows Geothermal Development Project faced a fierce legal challenge this past year. Geothermal, like hydroelectric dams, is often cited as a renewable energy source, since the technology harnesses heat from the earth to produce electricity, which in theory (as long as it doesn’t stop raining, surprise!), is endless.

Even so, large geothermal plants consume a lot of land and spit out a lot of water. The Dixie Meadows project, which was proposed in Nevada, was one such “green” energy plan that, if built, would suck up over 40,000 thousand acre-feet of water every single year, the result of which would be devasting. Dixie’s delicate wetlands habitat, unique to this stretch of the Great Basin, is home to the imperiled black-freckled Dixie Valley toad, and even a slight alteration of surface water conditions could spell extinction for this rare little toad. Birds too use Dixie’s natural spring water as migratory stopovers. Dixie Meadows is a literal oasis in the desert and has been for tens of thousands of years.

“The United States has repeatedly promised to honor and protect indigenous sacred sites, but then the BLM approved a major construction project nearly on top of our most sacred hot springs. It just feels like more empty words,” said Fallon Paiute-Shoshone Tribal Chairwoman Cathi Tuni following the announcement of the Dixie Meadows project. “This location has long been recognized as being of vital significance to the Tribe. There are geothermal plants elsewhere in Dixie Valley and the Great Basin that we have not opposed, but construction of this plant would build industrial power plants right next to a sacred place of healing and reflection, and risks damaging the water in the springs forever. We have a duty to protect the hot springs and its surroundings, and we will do so.”

On December 16, 2021, The Fallon Paiute-Shoshone Tribe and the Center of Biological Diversity (Center) sued the BLM over its approval of the Dixie Meadows geothermal project, and in early August were successful in stopping it from moving forward.

“I’m thrilled that yet again the bulldozers are grinding to a halt as a result of our legal actions,” said Patrick Donnelly, Great Basin director at the Center. “Nearly every scientist who has evaluated this project agrees that it puts the Dixie Valley toad in the crosshairs of extinction. This agreement gives the toad a fighting shot.”

***

About 270 miles south of Dixie Meadows, another “green” energy plan is in the works near the remote Searchlight, Nevada. The Kulning Wind Project, proposed by Eolus Vind AB, a Swedish power developer, is not unlike other wind projects that were halted in 2017 and 2018 after an outcry from local Tribes and conservationists. Kulning, like the prospects that were shot down, is massive and would include 68 wind turbines spanning 9,300 acres of federal lands on the site of the proposed Avi Kwa Ame (Ah-VEE kwa-meh) National Monument. Like Dixie Meadows, Kulning would greatly impact local wildlife.

“[The] development would likely undermine the use of the region by bighorn sheep and would introduce an unnecessary wildfire risk, threatening Wee Thump and South McCullough wildernesses, among many other concerns,” says Paul Selberg, director of Nevada Conservation League. “Decisions on where to develop renewable energy must be evaluated critically and placed in areas that are appropriate.”

The real question is; are expansive energy projects, be they fossil fuels or “green”, ever really “appropriate”? Indigenous communities and conservationists are wary.

The land outside Searchlight where these huge twirling wings are to be erected is considered a sacred “place of creation” to 12 local tribes, including the Havasupai, Hualapai, Kumeyaay, Maricopa, Mojave, Pai Pai, Quechan, and Yavapai. Opponents of the development, led by a broad coalition of tribes, point out that this stretch of the Mojave is some of the most pristine, in-tact wilderness in the Southwest.

Joshua trees (known as sovarampi to the Southern Paiute) in this area, which make up the largest Joshua forest in Nevada, will be destroyed if the project moves forward. These distinctive, twisted trees are already facing a bleak future in the West. Mojave’s high desert is becoming even hotter and drier than normal, dropping nearly 2 inches from its average of just over 4.5 inches of annual rainfall just a decade ago. The result: younger Joshua trees, which grow at a snail’s pace of 3 inches per year, are perishing before they reach a foot in height. Their vanishing is an indicator that these peculiar trees will not be replenished once they grow old and die, and they are dying at a startling rate.

While it has not received as much attention as Bears Ears or Gold Butte, Avi Kwa Ame National Monument is equally important as an ecological and cultural site, which would span 450,000 acres, protecting the delicate landscape from energy developers (to support the proposed monument, you can sign a petition here).

At the center of this onslaught of development is California’s quest to end the use of fossil fuels. Most of the energy in the state, one of the largest energy consumers in the country, is generated from utility-scale wind and solar, which, as of 2016, has required over 400,000 square kilometers of land to produce. This development, because it is billed as “green” energy, has received little scrutiny from the broader environmental movement. As a result, studies on the effects on biodiversity and threatened species, like the Desert Tortoise, are virtually non-existent.

***

In Northern Nevada, a similar fight is raging over Thacker Pass, where a proposed mine would produce upwards of 80,000 tons of lithium per year, a mineral that is crucial for most electric car batteries. Lithium Nevada, the company spearheading the Thacker project, is facing strong pushback from activists and members of Fort McDermitt Paiute and Shoshone, among others.

“Places like Thacker Pass are what gets sacrificed to create that so-called clean energy,” says author and activist Max Wilbert. “It is easy to say the sacrifice is justifiable if you do not live here.”

Indigenous communities are equally upset at the plan.

“Annihilating old-growth sagebrush, Indigenous peoples’ medicines, food, and ceremonial grounds for electric vehicles isn’t very climate conscious,” said Arlan Melendez, the chair of the Reno-Sparks Indian Colony.

Opposition to the lithium mine has invigorated a new, vibrant protest movement in Nevada, led by Indigenous activists that see these developments for what they are: a continuation of settler-colonialism, an onslaught fully supported by the Democrats and the Biden Administration. In the case of EVs, Biden’s 2021 American Jobs Plan earmarked $174 billion to promote electric vehicles. The Thacker mine, claims Lithium Nevada, is central to those efforts.

There are also alternatives to lithium like seawater, sodium, and glass batteries. While none are environmentally benign, the impacts do vary. Maria Helena Braga a scientist at the University of Porto in Portugal, who has been researching glass battery technology, believes glass has the brightest future. “It’s the most eco-friendly cell you can find,” claims Braga.

Recently, researchers at the University of California San Diego’s Center for Interdisciplinary Environmental Justice disagreed that we need to mine our way out of climate change, stating that in order to curb greenhouse gas emissions we would have to decrease our output by 80% over the next thirty years. EVs, they claim, would only reduce greenhouse gases by 6%. In other words, the destruction these mines cause is not worth such little benefit. A larger, far more significant transition is needed.

***

In addition to technological advances (and the need to consume less), the energy grid itself must be revamped, from centralized sources of energy like coal or natural gas to a decentralized network of producers, where existing homes and commercial buildings are required to install solar on their rooftops. Big utilities, like PG&E in California, which has been responsible for causing over 1,500 fires and hundreds of deaths in the state, are not pleased with the push for community-controlled, decentralized power. In fact, in an effort to disincentivize rooftop solar, California regulators, after heavy lobbying from energy companies, are currently pushing to slash residential solar incentives, making the transition even more difficult, while supporting large desert developments in the process.

Hundreds of plans for large renewable energy projects are currently in the works in California, New Mexico, and Nevada, and one by one they are set to destroy vast stretches of desert habitat. In 2015, researchers from UC Berkeley and UC Riverside looked at 161 proposed and operational solar plants. What they found was startling. Only 10-15 percent of the projects in California were located in areas that would have little impact on their surroundings. In other words, 85% of these would harm the environments where they’re located.

“We would hope that if a developer was on the ground and saw that, oh, this is a really important area for migratory birds, maybe we should look at that Walmart commercial roof down the road, and collaborate with them rather than putting it here,” said the study’s lead author Rebecca Hernandez, a scientist at UC Berkeley.

While the push for decentralizing is paramount, some argue that locating green energy installations in already impacted areas, like brownfields, is a good alternative. Yet this is rarely the most profitable choice. At the heart of the problem is that public lands in the desert west are inexpensive. The Bureau of Land Management leases huge parcels of these lands for dirt cheap, which in turn incentivizes large-scale wind and solar projects — projects that support Biden’s climate plan, where companies like PG&E will continue to control the grid and small-scale projects will be difficult and expensive to build.

If the goal of clean, green energy is to offset the wrath of climate catastrophe, yet damages sensitive habitats in the process, are these projects even worthwhile? That’s a question environmentalists and others must grapple with. Certainly, they are good for profit margins, but the evidence is mounting that they are also devastating to desert ecology.

JOSHUA FRANK is the managing editor of CounterPunch. He is the author of the forthcoming book, Atomic Days: The Untold Story of the Most Toxic Place in America, published by Haymarket Books. He can be reached at joshua@counterpunch.org. You can troll him on Twitter @joshua__frank.

Featured image by Antonio Garcia via Unsplash

by DGR News Service | Jun 20, 2022 | NEWS

Editor’s note: Lithium is among the hottest commodities today. As oil prices spike, electric vehicles (EVs) are sold out at dealerships and huge numbers of pre-orders serve as massive interest-free loans for EV corporations. But supply chains remain an obstacle to EV adoption.

Producing electric cars is more complex and expensive than internal-combustion-engine vehicles, and the infrastructure to support EV manufacturing—from mines to factories—is still in its infancy. This imbalance between supply and demand is driving prices up, while uncertainties in the market are threatening investment.

Those uncertainties include local communities around the world, from the United States to Chile, fighting to keep lithium mining from destroying their communities, as well as new threatening regulations in the European Union that classify lithium salts as serious reproductive toxins. The environmental impact of lithium mining and EV manufacturing is extremely serious, and community opposition is growing just as opposition to the oil and gas industry has grown.

Today’s story comes from Serbia, where determined resistance from environmentalists, farmers, and community members has succeeded in blocking Rio Tinto, the second-largest mining corporation in the world, from mining the Jadar valley for lithium borates.

by Binoy Kampmark / Counterpunch

… The Anglo-Australian mining giant [Rio Tinto] was confident that it would, at least eventually, win out in gaining the permissions to commence work on its US$2.4 billion lithium-borates mine in the Jadar Valley.

In 2021, Rio Tinto stated that the project would “scale up [the company’s] exposure to battery materials, and demonstrate the company’s commitment to investing capital in a disciplined manner to further strengthen its portfolio for the global energy transition.”

The road had been a bit bumpy, including a growing environmental movement determined to scuttle the project. But the ruling coalition, led by the Serbian Progressive Party, had resisted going wobbly on the issue…

[But now] In Serbia, Rio Tinto [has] faced a rude shock. The Vučić government, having praised the potential of the Jadar project for some years, abruptly abandoned it. “All decisions (connected to the lithium project) and all licenses have been annulled,” Serbian Prime Minister Ana Brnabić stated flatly on January 20. “As far as project Jadar is concerned, this is an end.”

Branabić insisted, somewhat disingenuously, that this decision merely acknowledged the will of voters. “We are listening to our people and it is our job to protect their interests even when we think differently.”

This is a bit rich coming from a government hostile to industry accountability and investment transparency. The same government also decided to begin infrastructure works on the jadarite mine before the granting of an exploitation permit. Such behavior has left advocates such as Savo Manojlović of the NGO Kreni-Promeni wondering why Rio Tinto was singled out over, for instance, Eurolithium, which was permitted to dig in the environs of Valjevo in western Serbia.

Zorana Mihajlović, Serbia’s mining and energy minister, preferred to blame the environmental movement, though the alibi seemed a bit forced. “The government showed it wanted the dialogue … (and) attempts to use ecology for political purposes demonstrate they (green groups) care nothing about the lives of the people, nor the industrial development.”

Rio Tinto had been facing an impressive grass roots militia, mobilized to remind Serbians about the devastating implications of proposed lithium mining operations. The Ne damo Jadar (We won’t let anyone take Jadar) group has unerringly focused attention on the secret agreements reached between the mining company and Belgrade. Zlatko Kokanović, vice president of the group, is convinced that the mine would “not only threaten one of Serbia’s oldest and most important archaeological sites, it will also endanger several protected bird species, pond terrapins, and fire salamander, which would otherwise be protected by EU directives.”

Taking issue with the the unflattering environmental record of the Anglo-Australian company, numerous protests were organized and petitions launched, including one that has received 292,571 signatures. Last month, activists organized gatherings and marches across the country, including road blockades.

Djokovic has not been immune to the growing green movement, if only to lend a few words of support. In a December Instagram story post featuring a picture of anti-mining protests, he declared that, “Clean air, water and food are the keys to health. Without it, every word about health is redundant.”

Rio Tinto’s response to the critics was that of the seductive guest keen to impress: we have gifts for the governors, the rulers and the parliamentarians. Give us permission to dig, and we will make you the envy of Europe, green and environmentally sound ambassadors of the electric battery and car revolution.

The European Battery Alliance, a group of electric vehicle supply chain companies, is adamant that the Jadar project “constituted an important share of potential European domestic supply.” The mine would have “contributed to support the growth of a nascent industrial battery-related ecosystem in Serbia, contributing to a substantial amount to Serbia’s annual GDP.” Assiduously selective, the group preferred to ignore the thorny environmental implications of the venture.

The options facing the mining giant vary, none of which would appeal to the board. In a statement, the company claimed that it was “reviewing the legal basis of this decision and the implications for our activities and our people in Serbia.” It might bullyingly seek to sue Belgrade, a move that is unlikely to do improve an already worn reputation. “For a major mining company to sue a state is very unusual,” suggests Peter Leon of law firm Herbert Smith Freehills. “A claim under the bilateral treaty is always a last resort, but not a first resort.”

Another option for punters within the company will be a political gamble: hoping that April’s parliamentary elections will usher in a bevy of pro-mining representatives. By then, public antagonism against matters Australian will have dimmed. The Serbian ecological movement, however, is unlikely to ease their campaign. The age of mining impunity in the face of popular protest has come to an end.

Dr. Binoy Kampmark was a Commonwealth Scholar at Selwyn College, Cambridge. He lectures at RMIT University, Melbourne. Email: bkampmark@gmail.com.

Minor edits have been made to this piece for clarity.