by DGR News Service | Jan 9, 2022 | Culture of Resistance, Gender, Male Supremacy, Women & Radical Feminism

This talk was given in the Feminist Thinking Will Save the Planet session at #FiLiA2021. The article originally appeared on the FiLiA website.

By Susan Breen

Any of you who know me will be aware that I’m a recovering mainstream environmentalist and left wing political candidate, for any of you who are active in either sphere I’m sure you have shared many of the same frustrations and demoralisations as I have done. I became an activist in my teens but despite being involved in the movement since then I had been pretty much politically homeless for my entire life.

Then fortunately one day I happened upon this:

“Men as a class are waging a war against women, rape, battering, incest, prostitution, pornography, poverty, and gynocide are both the main weapons in this war and the conditions that create the sex class women. Gender is not natural, not a choice, and not a feeling. It is the structure of women’s oppression. Attempts to create more “choices” within the sex caste system only serve to reinforce the brutal realities of male power. As radicals, we intend to dismantle gender and the entire system of patriarchy which it embodies. The freedom of women as a class cannot be separated from the resistance to the dominant culture as a whole”

This is an excerpt from the Deep Green Resistance statement of principles, and reading this affirmed to me that it was the lack of this understanding that limited my alignment with the mainstream environmental and political groups in which I was immersed.

This recognition of the interrelation of the struggles of women and the living world is one of the aspects of our analysis that people often seem to find the hardest to understand, so I’m going to speak a little about that, share some thoughts regarding obstacles facing female activists, and the importance of sisterhood in the work that we do.

Firstly, as radicals, we seek out the root of the problems facing us. These “problems” consist of material institutions of oppression and ideologies which sustain the narrative of the powerful.

The corrupt and brutal power arrangement of patriarchy needs an ideology and we call it gender. The parallels between the ideology of racism, necessary for white supremacy, may seem obvious, yet there appears to be endless resistance to applying a class analysis to the struggle of women. Even in the most “progressive” circles, there is a silent understanding that when push comes to shove women can always be used as collateral damage. Women are viewed in the same way as the living world, simply a natural resource to be used by the ruling male class as he sees fit.

On the left we see this in the cheerleading for the full decriminalisation of the sex trade, the cheerleading of gender recognition legislation stripping our sex based protections, the minimization of the continuum of male violence which every woman and girl is forced to navigate, and the perpetual dismissal of the value of our domestic labour which enables the family and society to function at all.

Ecofeminism challenges this commodification of women’s bodies, labour and knowledge, while also challenging the patriarchal reconceptualisation of nature as a machine, as a resource, and as an “other”.

So why do we need to challenge this? Let’s talk for a moment about where the capitalist patriarchy has brought us.

Current atmospheric C02 – 411.40ppm – for anyone who isn’t aware of the figures, anything above 350ppm is considered unsafe.

According to the 6th climate assessment by the intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change we have already warmed the planet by 1.2(Global temps Jan – Oct 2020) degrees above pre industrial levels. In 2019 the concentration of carbon in the atmosphere was higher than at any period in the last two million years, concentrations of methane and nitrous oxide – both more potent than C02, were higher than at any period in the last 800,000 years.

On our current trajectory we are expected to achieve a 1.5 degree temperature rise within 20 years from now. The IPCC authors worst case scenario emissions double by 2050 we would achieve a 2.4 degree rise by between 2041 and 2060. Then almost double by 2100

For anyone who’s unsure what that means, its game over.

For every half degree of warming the frequency and intensity of natural disasters increases. More wildfires, more flooding, more drought, more food scarcity, and increasingly violent resource wars

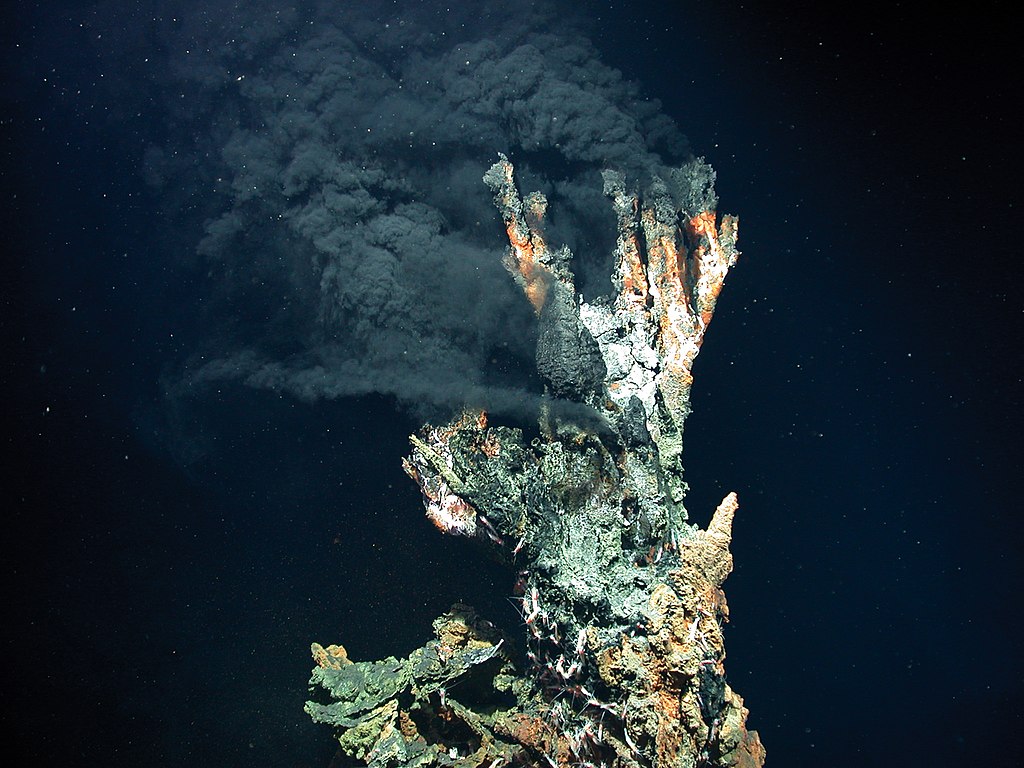

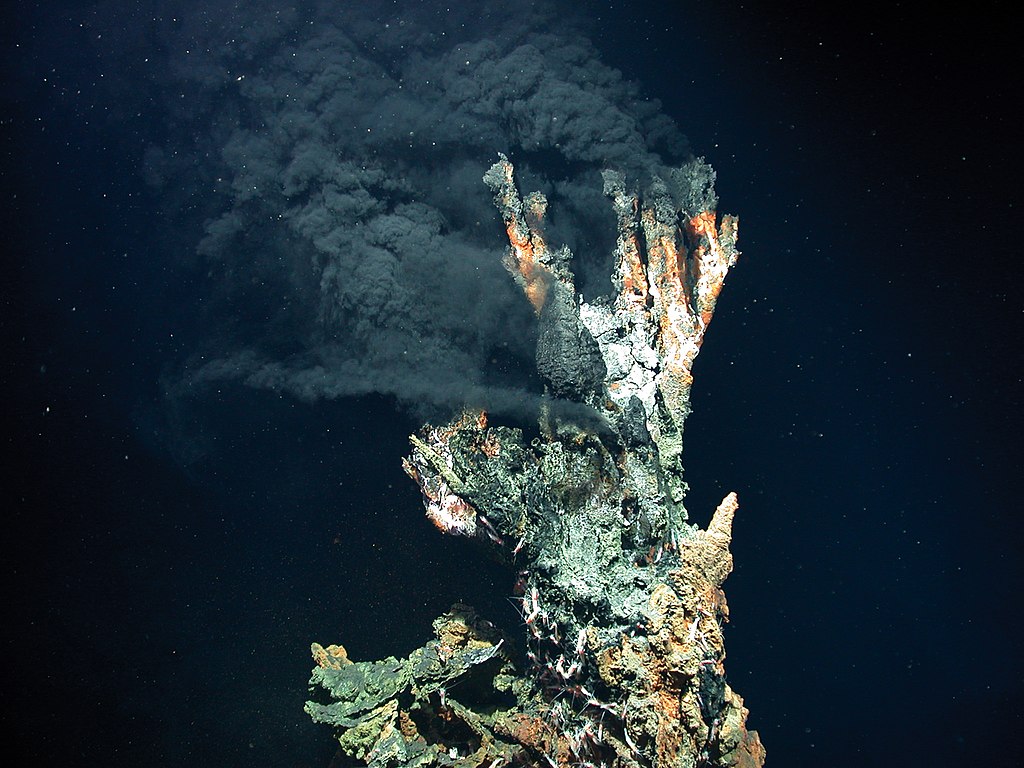

More than 90% of the heat trapped by humanity’s greenhouse gas emissions has been absorbed by the seas. Anthropogenic global warming has heated the oceans by the equivalent of one atomic bomb explosion per second for the past 150 years.

This means more acidification of our oceans, further devastation of marine life, and severe disruption of currents critical to seasonal weather patterns.

The emergence of new strains of zoonotic disease, and the expansion of vector borne diseases due to habitat destruction and warming climate.

Intensified neo-colonialism of global north companies which continue pillaging communities in the global south.

Last October we formed a coalition called Shale Must Fall which targets the fracking industry, connecting communities at extraction points and communities at the point of consumption. We attempt to bridge these communities and incorporate the testimonies of front line activists into global actions, targeting the headquarters/operations of these climate criminals.

Our members in Chihuahua gave us a stark insight into the reality of water shortage. Last September National Guard troops clashed with hundreds of farmers protesting the government decision to ship scarce water supplies from their drought stricken region to Texas. Due to the 1944 Water Treaty, the water was “owed” to the US.

One woman was shot dead during the standoff and others injured. It is strongly suspected that the Mexican water was bound for the fracking industry in Texas, while the people of Chihuahua were denied water to drink, wash and farm.

Similar horrors are playing out in the Okavango Delta, where a Canadian company – ReconAfrica plan to frack one of the great delta’s of the world and the wealth of life that she sustains. Our activists in the region are fighting this company, some are mothers, carrying young children on their hips while facing threats of violence and death.

As resources dwindle, this is the future we face. The merciless destruction of non human and human communities as industry, protected by government, continues to devour what’s left in a desperate attempt to maintain their malignant infinite growth model on our finite and fragile home.

And what does all this mean for women?

Climate collapse compounds and magnifies existing inequalities, dangers and the risk and occurrence of male violence, so let’s talk a little about what women are facing currently:

UN figures indicate that 80% of people displaced by climate change are women. Roles as primary care givers and food providers making us more vulnerable.

As we all know women are more likely to experience poverty and to have less socioeconomic power than men making it more difficult to recover from disasters which affect infrastructure, jobs and housing.

An example of this is after Hurricane Katrina more than half the poor families in New Orleans were single mothers dependent on community networks for resources and survival. The disaster eroded those support networks placing women and children at far greater risk.

An Oxfam report into the 2004 tsunami found that surviving men outnumbered women by almost 3:1 in Sri Lanka, Indonesia and India. It appears that women lost precious evacuation time trying to save children and other relatives.

Another study spanning 20 years noted that catastrophic events lowered women’s life expectancy more than men; more women were being killed, or being killed younger. The difference reduced in countries where they had greater socioeconomic power.

As for male violence

- According to UNIFEM in South Africa a woman is killed every 6 hours by an intimate partner.

- A woman is reported beaten every 18 seconds in the US.

- A 2007 study found that 22 women in India were killed each day due to dowry related murders.

- In Guatemala, two women are murdered on average every day.

- In India a woman is reported raped every 20 minutes.

- More than 60 million girls worldwide are child brides

- In Sao Paulo, Brazil a woman is assaulted every 5 seconds.

- UNITE estimates that up to 70% of women experience violence in their lifetime.

- World Bank data indicates that amongst women ages 15 – 44 acts of male violence cause more death and disability than from cancer, car accidents, war and malaria combined.

The pathology of masculinity is ravaging women and life on this planet, and its structures will not have a spontaneous change of heart. The capitalist patriarchy will continue to destroy until it is stopped by force, and we as women are the only ones who can lead this.

Patriarchy

Rosemary Radford Ruether said; “Women must see that there can be no liberation for them and no solution to the ecological crisis within a society whose fundamental model of relationships continues to be one of domination.”

In this age of science and development we are funneled into a productivist mode of interaction, rather than a relational mode of interaction, with nature, women and children suffering most within this sterile framework. Capitalism, individualism and masculinity have created a perfect storm, destroying the balance of organic communication and connection.

Central to masculinity is the male violation imperative.

Lierre Kieth writes;

“Masculinity requires what psychologists call a negative reference group, which is the group of people “that an individual … uses as a standard representing, opinions, attitudes or behavioral patterns to avoid”. Boys in patriarchal cultures create negative reference groups as a matter of course. Boys first despised other is, of course, girls. No insult is worse than some version of “girl”, usually a part of the female anatomy warped into hate speech. But once the psychological process is in place, the category ”female” can easily be filled with any group that a hierarchical society needs dominated or eradicated.

A personality with an endless drive to prove itself against another, any other, combined with the entitlement that power brings, creates a violation imperative. Men become ‘real men’ by breaking boundaries, whether it’s the sexual boundaries of women, the cultural boundaries of other peoples, the political boundaries of other nations, the genetic boundaries of species, the biological boundaries of living communities, or the physical boundaries of the atom itself

The real brilliance of patriarchy is that it doesn’t just naturalize oppression. It sexualizes acts of oppression. It eroticizes domination and subordination, and then it takes that eroticized domination and subordination, and institutionalizes that into masculinity and femininity. So it naturalizes, it eroticizes, and then it institutionalizes.

The brilliance of feminism is that we figured that out.”

We are living within overlapping systems of oppression. He would like us to think that it’s inevitable, that it’s human nature, but its not.

According to indigenous wisdom the world is made up of live, sentient beings to be in relationship with, individual obligations to fulfill to allow the entire web of life to function.

To the mind of the dominant culture the world is made up dead resources, objects to sell and orifices to fuck. Neoliberalism and identity politics have ensured a myopic culture of individualism. The aim is to disconnect us from the land, from each other, and even from our own bodies, which this culture teaches us to despise and contort from early childhood.

This lie of disconnection is embedded into our religions, laws and economics. These systems have all been designed to maintain an unnatural social order for his benefit, and here he has brought us to the brink of extinction, bloodied, brutalised but still resisting, because as women we know it doesn’t have to be this way, in our bones we can remember another world, and every one of us still carries it with us.

The Matriarchy

Renowned matriarchal historian Heide Göttner-Abendroth writes;

“Therefore, from the political point of view, I call matriarchies egalitarian societies of consensus. These political patterns do not allow the accumulation of political power. In exactly this sense, they are free of domination: They have no class of rulers and no class of suppressed people, and they need no ’enforcement bodies’ such as warriors, police, or controlling and punishing institutions that are necessary to establish domination of a majority of people”

We know this was a reality for thousands of years, and if there is to be any hope for women or for the Earth it must become reality again.

Taking power back – Organising as women

To organise effectively as women we need, above all else, true sisterhood and solidarity. How do we take the learnings from matriarchal organising and apply them to our own organisations and campaigns?

As in any other area of life, there can be enormous pressure to replicate the dominant culture within our group dynamics. Like mothers we need ferocious gentleness, protectiveness and loyalty. Sometimes it is difficult to maintain focus, but it’s vital that we refuse to loose sight of our common cause and that we employ a great deal of forgiveness and understanding for the women we work alongside.

Moving through politics and activism as a working class single parent I’ve witnessed a stark lack of recognition of class privilege. The reality of working class women and mothers is unique, as is their perspective. To be inclusive of those voices, and other women facing constraints, the hierarchies of time, money and education need to be taken into account and adapted for. if we want to be in solidarity with women who are often the most vulnerable in our communities we need to organise with them in mind. We need to practice what we preach so all women are empowered to become part of the movement.

Obstacles

Controlled opposition– as activists we need to constantly assess the efficacy of our actions, the possible repercussions and the impact on our targets. We need to be aware of how the media and the state will use our movements to suit their own ends. We need to be well educated and aware of how government forces infiltrate, co-opt, and neutralize activist networks.

False solutions – The false belief that technology can save us, that more extractivism, more industry, more destruction of habitat will somehow make our way of life sustainable. The environmental movements role should be to protect the living world, not to protect our way of life or to reinforce the culture of empire.

The false belief that we can somehow negotiate with those in power – Electoral politics and NGO’s have proven themselves untrustworthy time and time again, resistance must come from the grassroots. There is a dangerous belief that within the dominant culture there is a willingness to change but power never ceded power voluntarily. We are at war, at war for the survival of the living world and at war for our right to exist as women.

Disconnection – From ’Demon Lover – On the Sexuality of Terrorism’ by Robin Morgans:

“If I had to name one quality as the genius of patriarchy it would be compartmentalisation, the capacity for institutionalising disconnection. Intellect severed from emotion. Thought separated from action … the personal isolated from the political, Sex divorced from love. The material ruptured from the spiritual

If I had to name one quality as the genius of feminist thought, culture, and action. It would be connectivity.”

This connection allows us to be fully aware of our sisters.

Awareness of our socialisation, unpacking our need to always be kind and accommodate. Being fully aware of each other enables us to genuinely support other women when they are setting boundaries for themselves and for others.

Awareness of our persistence – in the face of poverty, oppression, responsibility, isolation … persistence in the face of drudgery… behind every event, every action, every protest, there are a million emails, phone calls, conversations … women in the background swimming in a sea of administrative boredom and stress. Recognition and gratitude couldn’t be more important.

Despair – Despair can be debilitating – images that feel like a punch to your stomach – clear cuts, oceans of plastic, emaciated polar bears, orangutans clinging to burned and broken branches, their babies clinging to their dead mothers, scorched kangaroos hanging on barbed wire fences.

I think of the stealth of the silence all around me. Less birds, less bees, less insects.

I think of all the girls living under patriarchy, we all have some that haunt us, replay in our minds over and over.

I think of Ana Kriegel, a lonely 14 year old girl. Lured from her home by the schoolboy she had a crush on. He took her and his friend to an abandoned building where he sexually assaulted her then beat her to death as the other looked on, ignoring her screams for help. They were 13 years old, reenacting his favourite porn scene.

I think of the little 5 year old girl in India who’s name I don’t even know, she was taken from her sleeping mothers arms in a train station and murdered by two men.

Despair can be overwhelming, and that’s exactly what he wants – for us to be overwhelmed and contracted in fear, and sometimes it’s almost impossible to resist. But we do have an antidote to the despair, all we need is to look to the courageous examples of other women. Women who against all the odds are fighting back, resisting, creating beauty – I think of the women of Rojava, the women marching against the Taliban in the streets of Kabul, The Gulabi gang.

All the women who I know struggling on the frontlines of Earth defense.

I think of weeds creeping through concrete.

60% of our bodies are on loan from the seas and rivers, our menstrual cycles are intimately connected to the moons and the tides. We are so intertwined with each other that our bleeding can synchronize in time with our sisters. All of life moves through us, and all of life is fighting back and willing us to resist.

Rachel Carson wrote; “Those who contemplate the beauty of the Earth find reserves of strength that will endure as long as life lasts. There is something infinitely healing in the repeated refrains of nature – the assurance that dawn comes after night, and Spring after Winter.”

And dawn will come, and Spring after, because we really can do this, but only if we are unified in our struggles. We have all experienced the feeling of genuine female solidarity, working together for a common purpose. The power and potential is undeniable. We know this in our bones and so do the patriarchs, that’s why they have spent the last 6,000 years trying to stamp it out.

To be female under patriarchy is to be brutalised, to be nature under capitalism is to be devoured, he demands our submission while making a hellscape of our paradise and commodities of our sisters.

There are only two forces on this planet with the beauty and ferocity to stop him.

Wild nature and wild woman.

—

About Sue Breen

Raised by environmentalist parents, Sue took part in her first direct action aged seventeen. Since then activism has been a central passion in her life. Influenced by a her radical feminist mother, she was a lead campaigner for the ‘Together for Yes’ abortion rights campaign and is currently a member of The Irish Women’s Lobby. Sue spent a number of years working as an international coordinator for Extinction Rebellion and also ran as a left-wing political candidate. Finally finding her true political home, she is now an organiser with radical feminist environmental organisation Deep Green Resistance. She is also a founding member of the Shale Must Fall coalition which focuses on targeting the fracking industry, unifying impacted communities, and highlighting the neocolonialism carried out by Western corporations. Sue is a single mother to three girls, a complimentary therapist, and is beginning an apprenticeship in herbal medicine.

Banner image by Lindsey LaMont at Unsplash.

by DGR News Service | Dec 17, 2021 | Biodiversity & Habitat Destruction, Climate Change, Colonialism & Conquest, Human Supremacy, The Problem: Civilization, The Solution: Resistance

This article was produced by Local Peace Economy, a project of the Independent Media Institute.

By Koohan Paik-Mander

The U.S. military is famous for being the single largest consumer of petroleum products in the world and the largest emitter of greenhouse gases. Its carbon emissions exceed those released by “more than 100 countries combined.”

Now, with the Biden administration’s mandate to slash carbon emissions “at least in half by the end of the decade,” the Pentagon has committed to using all-electric vehicles and transitioning to biofuels for all its trucks, ships and aircraft. But is only addressing emissions enough to mitigate the current climate crisis?

What does not figure into the climate calculus of the new emission-halving plan is that the Pentagon can still continue to destroy Earth’s natural systems that help sequester carbon and generate oxygen. For example, the plan ignores the Pentagon’s continuing role in the annihilation of whales, in spite of the miraculous role that large cetaceans have played in delaying climate catastrophe and “maintaining healthy marine ecosystems,” according to a report by Whale and Dolphin Conservation. This fact has mostly gone unnoticed until only recently.

There are countless ways in which the Pentagon hobbles Earth’s inherent abilities to regenerate itself. Yet, it has been the decimation of populations of whales and dolphins over the last decade—resulting from the year-round, full-spectrum military practices carried out in the oceans—that has fast-tracked us toward a cataclysmic environmental tipping point.

The other imminent danger that whales and dolphins face is from the installation of space-war infrastructure, which is taking place currently. This new infrastructure comprises the development of the so-called “smart ocean,” rocket launchpads, missile tracking stations and other components of satellite-based battle. If the billions of dollars being plowed into the 2022 defense budget for space-war technology are any indication of what’s in store, the destruction to marine life caused by the use of these technologies will only accelerate in the future, hurtling Earth’s creatures to an even quicker demise than already forecast.

Whale Health: The Easiest and Most Effective Way to Sequester Carbon

It’s first important to understand how whales are indispensable to mitigating climate catastrophe, and why reviving their numbers is crucial to slowing down damage and even repairing the marine ecosystem. The importance of whales in fighting the climate crisis has also been highlighted in an article that appeared in the International Monetary Fund’s Finance and Development magazine, which calls for the restoration of global whale populations. “Protecting whales could add significantly to carbon capture,” states the article, showing how the global financial institution also recognizes whale health to be one of the most economical and effective solutions to the climate crisis.

Throughout their lives, whales enable the oceans to sequester a whopping 2 billion metric tons of carbon dioxide per year. That astonishing amount in a single year is nearly double the 1.2 billion metric tons of carbon that was emitted by the U.S. military in the entire 16-year span between 2001 and 2017, according to an article in Grist, which relied on a paper from the Costs of War Project at Brown University’s Watson Institute.

The profound role of whales in keeping the world alive is generally unrecognized. Much of how whales sequester carbon is due to their symbiotic relationship with phytoplankton, the organisms that are the base of all marine food chains.

The way the sequestering of carbon by whales works is through the piston-like movements of the marine mammals as they dive to the depths to feed and then come up to the surface to breathe. This “whale pump” propels their own feces in giant plumes up to the surface of the water. This helps bring essential nutrients from the ocean depths to the surface areas where sunlight enables phytoplankton to flourish and reproduce, and where photosynthesis promotes the sequestration of carbon and the generation of oxygen. More than half the oxygen in the atmosphere comes from phytoplankton. Because of these infinitesimal marine organisms, our oceans truly are the lungs of the planet.

More whales mean more phytoplankton, which means more oxygen and more carbon capture. According to the authors of the article in the IMF’s Finance and Development magazine—Ralph Chami and Sena Oztosun, from the IMF’s Institute for Capacity Development, and two professors, Thomas Cosimano from the University of Notre Dame and Connel Fullenkamp from Duke University—if the world could increase “phytoplankton productivity” via “whale activity” by only 1 percent, it “would capture hundreds of millions of tons of additional CO2 a year, equivalent to the sudden appearance of 2 billion mature trees.”

Even after death, whale carcasses function as carbon sinks. Every year, it is estimated that whale carcasses transport 190,000 tons of carbon, locked within their bodies, to the bottom of the sea. That’s the same amount of carbon produced by 80,000 cars per year, according to Sri Lankan marine biologist Asha de Vos, who appeared on TED Radio Hour on NPR. On the seafloor, this carbon supports deep-sea ecosystems and is integrated into marine sediments.

Vacuuming CO2 From the Sky—a False Solution

Meanwhile, giant concrete-and-metal “direct air carbon capture” plants are being planned by the private sector for construction in natural landscapes all over the world. The largest one began operation in 2021 in Iceland. The plant is named “Orca,” which not only happens to be a type of cetacean but is also derived from the Icelandic word for “energy” (orka).

Orca captures a mere 10 metric tons of CO2 per day—compared to about 5.5 million metric tons per day of that currently sequestered by our oceans, due, in large part, to whales. And yet, the minuscule comparative success by Orca is being celebrated, while the effectiveness of whales goes largely unnoticed. In fact, President Joe Biden’s $1 trillion infrastructure bill contains $3.5 billion for building four gigantic direct air capture facilities around the country. Nothing was allocated to protect and regenerate the real orcas of the sea.

If ever there were “superheroes” who could save us from the climate crisis, they would be the whales and the phytoplankton, not the direct air capture plants, and certainly not the U.S. military. Clearly, a key path forward toward a livable planet is to make whale and ocean conservation a top priority.

‘We Have to Destroy the Village in Order to Save It’

Unfortunately, the U.S. budget priorities never fail to put the Pentagon above all else—even a breathable atmosphere. At a December 2021 hearing on “How Operational Energy Can Help Us Address Logistics Challenges” by the Readiness Subcommittee of the U.S. House Armed Services Committee, Representative Austin Scott (R-GA) said, “I know we’re concerned about emissions and other things, and we should be. We can and should do a better job of taking care of the environment. But ultimately, when we’re in a fight, we have to win that fight.”

This logic that “we have to destroy the village in order to save it” prevails at the Pentagon. For example, hundreds of naval exercises conducted year-round in the Indo-Pacific region damage and kill tens of thousands of whales annually. And every year, the number of war games, encouraged by the U.S. Department of Defense, increases.

They’re called “war games,” but for creatures of the sea, it’s not a game at all.

Pentagon documents estimate that 13,744 whales and dolphins are legally allowed to be killed as “incidental takes” during any given year due to military exercises in the Gulf of Alaska.

In waters surrounding the Mariana Islands in the Pacific Ocean alone, the violence is more dire. More than 400,000 cetaceans comprising 26 species were allowed to have been sacrificed as “takes” during military practice between 2015 and 2020.

These are only two examples of a myriad of routine naval exercises. Needless to say, these ecocidal activities dramatically decrease the ocean’s abilities to mitigate climate catastrophe.

The Perils of Sonar

The most lethal component to whales is sonar, used to detect submarines. Whales will go to great lengths to get away from the deadly rolls of sonar waves. They “will swim hundreds of miles… and even beach themselves” in groups in order to escape sonar, according to an article in Scientific American. Necropsies have revealed bleeding from the eyes and ears, caused by too-rapid changes in depths as whales try to flee the sonar, revealed the article.

Low levels of sonar that may not directly damage whales could still harm them by triggering behavioral changes. According to an article in Nature, a 2006 UK military study used an array of hydrophones to listen for whale sounds during marine maneuvers. Over the period of the exercise, “the number of whale recordings dropped from over 200 to less than 50,” Nature reported.

“Beaked whale species… appear to cease vocalising and foraging for food in the area around active sonar transmissions,” concluded a 2007 unpublished UK report, which referred to the study.

The report further noted, “Since these animals feed at depth, this could have the effect of preventing a beaked whale from feeding over the course of the trial and could lead to second or third order effects on the animal and population as a whole.”

The report extrapolated that these second- and third-order effects could include starvation and then death.

The ‘Smart Ocean’ and the JADC2

Until now, sonar in the oceans has been exclusively used for military purposes. This is about to change. There is a “subsea data network” being developed that would use sonar as a component of undersea Wi-Fi for mixed civilian and military use. Scientists from member nations of the Institute of Electrical and Electronics Engineers (IEEE), including, but not limited to Australia, China, the UK, South Korea and Saudi Arabia, are creating what is called the “Internet of Underwater Things,” or IoUT. They are busy at the drawing board, designing data networks consisting of sonar and laser transmitters to be installed across vast undersea expanses. These transmitters would send sonar signals to a network of transponders on the ocean surface, which would then send 5G signals to satellites.

Utilized by both industry and military, the data network would saturate the ocean with sonar waves. This does not bode well for whale wellness or the climate. And yet, promoters are calling this development the “smart ocean.”

The military is orchestrating a similar overhaul on land and in space. Known as the Joint All-Domain Command and Control (JADC2), it would interface with the subsea sonar data network. It would require a grid of satellites that could control every coordinate on the planet and in the atmosphere, rendering a real-life, 3D chessboard, ready for high-tech battle.

In service to the JADC2, thousands more satellites are being launched into space. Reefs are being dredged and forests are being razed throughout Asia and the Pacific as an ambitious system of “mini-bases” is being erected on as many islands as possible—missile deployment stations, satellite launch pads, radar tracking stations, aircraft carrier ports, live-fire training areas and other facilities—all for satellite-controlled war. The system of mini-bases, in communication with the satellites, and with aircraft, ships and undersea submarines (via sonar), will be replacing the bulky brick-and-mortar bases of the 20th century.

Its data-storage cloud, called JEDI (Joint Enterprise Defense Infrastructure), will be co-developed at a cost of tens of billions of dollars. The Pentagon has requested bids on the herculean project from companies like Microsoft, Amazon, Oracle and Google.

Save the Whales, Save Ourselves

Viewed from a climate perspective, the Department of Defense is flagrantly barreling away from its stated mission, to “ensure our nation’s security.” The ongoing atrocities of the U.S. military against whales and marine ecosystems make a mockery of any of its climate initiatives.

While the slogan “Save the Whales” has been bandied about for decades, they’re the ones actually saving us. In destroying them, we destroy ourselves.

Koohan Paik-Mander, who grew up in postwar Korea and in the U.S. colony of Guam, is a Hawaii-based journalist and media educator. She is a board member of the Global Network Against Weapons and Nuclear Power in Space, a member of the CODEPINK working group China Is Not Our Enemy, and an advisory committee member for the Global Just Transition project at Foreign Policy in Focus. She formerly served as campaign director of the Asia-Pacific program at the International Forum on Globalization. She is the co-author of The Superferry Chronicles: Hawaii’s Uprising Against Militarism, Commercialism and the Desecration of the Earth and has written on militarism in the Asia-Pacific for the Nation, the Progressive, Foreign Policy in Focus and other publications.

Banner image: flickr (CC BY-NC-ND 2.0)

by DGR News Service | Dec 12, 2021 | Alienation & Mental Health, Biodiversity & Habitat Destruction, Climate Change, Mining & Drilling, Music & Art, Protests & Symbolic Acts, The Problem: Civilization, Toxification

This article first appeared on the Association for the Tree of Live Website.

By JEAN ARNOLD

A ravenous, yet decrepit cyborg – part machine, part zombie – lurches onward as it is programmed to do. Its hunger is so insatiable that it eats its own flesh; it eats its offspring; and it eats the future. The catabolic effects are inescapable and its death rattle reverberates for miles. An entire city lives inside this beast. Yet in this late hour, inhabitants put their heads down and carry-on as usual, for they are all dependent upon this monster for their very own food, water, and shelter. No one dares utter a stray word, until the day one brave soul holds up a mirror that reveals who they have become.

A decade ago, I attended a series of contentious activist meetings with Rio Tinto, the mega-mining corporation that owns the massive Kennecott copper pit in the Salt Lake Valley. Rio Tinto planned to expand the mine, and activists were pushing back. The meetings foundered and collapsed upon the lack of viable possibilities for avoiding local impacts and for making operations more sustainable. Activists’ proposals were considered impractical and unprofitable. Ultimately, Kennecott got its expansion and activists got nothing.

Jean Arnold, Civilization, 2012, oil on canvas, 42 x 42 inches.

An early Egyptian pyramid is seen with the gaping hole of the Kennecott copper pit. As civilization builds up monuments to itself, it must tear down into Earth for her treasures.

As a visual artist, I took my angst to the studio and captured eviscerated earth in a series of paintings and drawings, depicting large-scale mining operations that are rarely seen or considered by the public. What better way to reveal our civilization’s insatiable hunger for resources?

I realized that the mining industry cannot be greened, intrinsically by its very nature. Mining casts a long shadow: habitat loss, land theft, worker exploitation, local health impacts, and groundwater contamination, to name just a few issues. Without mining and other forms of extraction, Industrial Civilization could not exist. Yet we rarely ponder our Wonder-World’s material basis and its extraction costs.

Turns out I’m not the only one working in this vein – far from it.

This year a broad panoply of photographers, painters, poets, and printmakers are raising a ruckus in a four-continent constellation of almost sixty exhibits, installations, performances, and events under the rubric “EXTRACTION: Art on the Edge of the Abyss.” When EXTRACTION originator Peter Koch announced the project, it took off like wildfire. Creators are shining lights on all forms of the omnivorous extractive industry, “from mining and drilling to the reckless plundering and exploitation of fresh water, fertile soil, timber, marine life, and innumerable other resources across the globe.” The project’s broad definition begs the questions: In our civilization, what isn’t based on extraction? What isn’t affected by extraction?

The Algonquin word “wetiko” reveals extraction as a symptom of the culture-wide soul-sickness driven by domination, greed, and consumptive excess. It blinds humans from seeing ourselves as part of an interdependent whole, in communion with all of life. It is through this toxic mindset that the world is divided up and consumed for profit.

Extraction is an uncomfortable topic: it confronts us with our system’s voracious appetite for taking Earth’s riches without reciprocity – the very epitome of wetiko. Sure, we can point at capitalism, corporations and elite interests, but as participants in this wetiko culture we are all infected by this mind virus.

Far beyond a “problem” – extraction and its consequences pose a predicament without escape. Humanity is hitting planetary limits: declining resources, excess CO2 in the atmosphere, and plastic choking our oceans. Many of the proposed “solutions,” are just new iterations of the same paradigm, bringing more extraction. For example, see our blog “We are Strip-Mining Life While We Drink ‘Bright Green Lies’” as to why “green” tech will never save us. Humanity has dug itself deep into a hole from which few of us may emerge.

Since stories create meaning, the “wetikonomy” seeks to maintain itself through a tight control over its own narratives. In our situation, the system rewards those that uphold its delusions: endless growth, techno-magic, fulfillment through consumption, and superiority over nature. We are told there is no alternative and things are getting better all the time.

Stephen Braun, The Hoarder, 2009, raku ceramics, 24 x 30 x 8 inches.

Clinging to the same mentality at the root cause of the crises.

The pressure to act according to these grand-yet-contradictory narratives is pervasive, which means compliance is near-universal. Witness the charades played by world leaders and diplomats at decades of climate conferences, giving lip service to fossil fuel phase-out while maintaining the techno-growth-extraction paradigm – essentially mocking the stated climate goals by clinging to the same mentality at the root cause of the crisis. Does anyone think this year’s climate conference, COP26 in Glasgow will play out differently?

Why are people so willing to surrender their agency? Society is captivated by a grand bargain described by social critic Lewis Mumford in his 1964 essay “Authoritarian and Democratic Technics”:

The bargain … takes the form of a magnificent bribe … each member of the community may claim every material advantage … food, housing, swift transportation, instantaneous communication, medical care, entertainment, education. But on one condition: that one must not merely ask for nothing that the system does not provide, but likewise agree to take everything offered … Once one opts for the system no further choice remains.

In other words, the bribe offers everyone a share in the largess, that is, the cornucopia of material goods unleashed by this industrial economy — as long as one does not question the costs to others, to ecosystems, or to the future.

The wetiko-spirit hates to be seen and named, as this begins to dissolve its parasitic power over its host. Dissent against the existing paradigm is ignored, penalized, or co-opted – that is, absorbed into the hegemony. Until it’s not. The time comes when costs become unbearable, limits are reached, and opposition finally boils over.

Thus, the last thing the power structure wants is a cultural spotlight on extraction, which exposes the core of our malady. And certainly not through art, which has a visceral, soul-level power – a power that scientific reports, statistics, and warnings do not have. Art can play a prophetic role: bearing witness to unsettling matters and grabbing attention before we can turn away. It can portray possibilities previously unconsidered, vitally needed at this time.

Jos Sances, Or, the Whale, 2108-2109, scratchboard, 14 x 51 feet

This very large scratchboard drawing was inspired by Moby Dick and the history of whaling in America. The whale’s skin is embedded with a history of capitalism in America—images of human and environmental exploitation and destruction since 1850.

EXTRACTION co-founder Edwin Dobb (now deceased) posed the question of our time: Can we break the spell? A growing chorus on the periphery – Greta Thunberg, poets, painters, performance artists, Extinction Rebellion – is revealing the sociopathic end-game holding us in its grip and unraveling slowly in real time. Learning to see wetiko within ourselves and our culture can begin to break its spell. Can we come to see our own hubris? Contraction is coming whether we like it or not – how can we deal with this if we are spellbound? We have no individual or collective roadmap for the coming post-extraction Reality.

The EXTRACTION project’s exhibits and events are winding down, although organizers hope for continuation in some form. Only a few more venues are scheduled to open, yet its effects will continue rippling outwards. The project has legitimized the extraction art movement and showcased some of today’s most potent work. It has broadened my own definition of extraction-inspired art, which helps me see new possibilities. The project will live on in the evolving work of extraction artists and in others forging authentic responses to our global predicaments. Art is all-too-often wed to money and societal embrace, compromising its own power and obscuring rather than illuminating Reality. Artmaking on the margins is not easy, so supporting this work is necessary.

Chris Boyer, Atlantic Salmon Pens, Welshpool, New Brunswick, Canada (44.885980°, -66.959243°), 2018.

Art that challenges the wetiko-extraction paradigm will become even more relevant, as extraction’s impacts widen. Extraction art is not going away, until extraction itself goes away. While industrial-scale extraction has “only” been with us for four hundred years, art has been with us for thousands of generations, since our early ancestors rendered images inside caves.

Listen to an audio of this blog, narrated by Michael Dowd.

Learn more about the EXTRACTION project.

EXTRACTION megazine (648 pages): download for free or purchase a printed copy for $25 + $7 shipping.

Partly a group catalog of extraction-related artwork, each artist or creator’s individual contribution documents their own personal investigations into the extraction question. The project is by no means limited to the visual arts—in these pages you will also find poetry, critical writings, philosophical treatises, manifestos, musical scores, conversations, historical or found photographs, and much more.

Make a donation to the EXTRACTION project.

by DGR News Service | Nov 24, 2021 | Biodiversity & Habitat Destruction, Human Supremacy, Mining & Drilling, The Problem: Civilization

This story first appeared in Mongabay.

Editor’s note: O Canada! Welcome to the new wild west. If you liked Deepwater Horizon you will love Deep Sea Mining. This statement pretty much sums it up, “countries could have their chance to EXPLOIT the valuable metals locked in the deep sea.” Corporations love to deal with poorer, less developed countries who can do less by way of supervision because they lack greater resources and capacity.

“Like NORI, TOML began its life as a subsidiary of Nautilus minerals, one of the world’s first deep-sea miners. Just before Nautilus’s project in Papua New Guinea’s waters failed and left the country $157 million in debt, its shareholders created DeepGreen. DeepGreen acquired TOML in early 2020 after Nautilus filed for bankruptcy, the ISA said the Tongan government allowed the transfer and reevaluating the company’s background was not required.”

And mining royalties are paid to the ISA. If this doesn’t sound fishy, I don’t know what does. There never should be a question as to what a corporation’s angle is. Their loyalty always is to the stockholders.

By Ian Morse

- Citizens of countries that sponsor deep-sea mining firms have written to several governments and the International Seabed Authority expressing concern that their nations will struggle to control the companies and may be liable for damages to the ocean as a result.

- Liability is a central issue in the embryonic and risky deep-sea mining industry, because the company that will likely be the first to mine the ocean floor — DeepGreen/The Metals Company — depends on sponsorships from small Pacific island states whose collective GDP is a third its valuation.

- Mining will likely cause widespread damage, scientists say, but the legal definition of environmental damage when it comes to deep-sea mining has yet to be determined.

Pelenatita Kara travels regularly to the outer islands of Tonga, her low-lying Pacific Island home, to educate fishers and farmers about seabed mining. For many of the people she meets, seabed mining is an unfamiliar term. Before Kara began appearing on radio programs, few people knew their government had sponsored a company to mine minerals from the seabed.

“It’s like talking to a Tongan about how cold snow is,” she says. “Inconceivable.”

The Civil Society Forum of Tonga, where Kara works, and several other Pacific-based organizations have written to several governments and the International Seabed Authority (ISA) to express concerns that their countries may end up being responsible for environmental damage that occurs in the mineral-rich Clarion-Clipperton Zone, an expanse of ocean between Hawai‘i and Mexico.

“The Pacific is currently the world’s laboratory for the experiment of Deep Seabed Mining,” the groups wrote to the ISA, the U.N.-affiliated body tasked with regulating the nascent industry. As a state that sponsors a seabed mining company, Tonga has agreed to shoulder a significant amount of responsibility in this fledgling industry that may threaten ecosystems that are barely understood. And if anything goes wrong in the laboratory, Kara is worried that Tonga’s liabilities could exceed its ability to pay. If no one can pay for remediation, Greenpeace notes, that may be even worse.

“My concern is that the liability from any problem with deep-sea mining will just be too much for us,” Kara says.

Another Pacific Island state, Nauru, notified the ISA in June that a contractor it sponsors is applying for the world’s first deep-sea mining exploitation permits. The announcement triggered the “two-year rule,” which compels the ISA to consider the application within that period, regardless of whether the exploitation rules and regulations are completed by then.

Among the rules that may not be decided upon by the deadline is liability: Who is responsible if something goes wrong? Sponsoring states like Nauru, Tonga and Kiribati — which all sponsor contractors owned by Canada-based DeepGreen, now The Metals Company — are required to “ensure compliance” with ISA rules and regulations. If a contractor breaches ISA rules, such as causing greater damage to ocean ecosystems than expected, the contractor may be held liable if the sponsoring state did all they could to enforce strict national laws.

However, it’s not yet clear how these countries can persuade the ISA that they enforced the rules, nor how they can prove that they are able to control the contractors, when the company is foreign-owned. The responsibility of sponsoring states to fund potentially billions of dollars in environmental cleanup depends on the legal definitions of terms like “environmental damage” and “effective control,” which may be as murky two years from now as they are at present.

Myriad problems may occur in the mining area: sediment plumes may travel thousands of kilometers and obstruct fisheries, or damage could spread into other companies’ areas. Scientists don’t know all the possible consequences, in part because these ecosystems are poorly understood. The ISA has proposed the creation of a fund to help cover the costs, but it’s not clear who will pay into it.

“The scales of the areas impacted are so great that restoration is just not feasible,” says Craig Smith, an oceanography professor emeritus at the University of Hawai‘i, who has worked with the ISA since its creation in 1994. “To restore tens or hundreds of thousands of square kilometers would be probably more expensive than the mining operation itself.”

Nauru voices concerns

Just over a decade ago, before Nauru agreed to sponsor a deep-sea mining permit, the government worried that it was going to find itself responsible for paying those damages. The government wrote to the International Tribunal for the Law of the Sea, voicing concerns about the liability it could incur. As a sponsoring state with no experience in deep-sea mining and a small budget to support it, the delegation wanted to make sure that the U.N. did not prioritize rich countries in charting this new frontier in mineral extraction. Nauru and other “developing” countries should have just as great an opportunity to benefit from mining as other countries with more experience in capital-intensive projects, they argued.

Sponsoring states like Nauru are required to ensure their contractors comply with the law but, the delegation wrote, “in reality no amount of measures taken by a sponsoring State could ever fully ‘secure compliance’ of a contractor when the contractor is a separate entity from the State.”

Seabed mining comes with risks — environmental, financial, business, political — which sponsoring states are required to monitor. According to Nauru’s 2010 request, “it is unfortunately not possible for developing States to perform their responsibilities to the same standard or on the same scale as developed States.” If the standards of those responsibilities varied according to the capabilities of states, the Nauru delegation wrote, both poor and rich countries could have their chance to exploit the valuable metals locked in the deep sea.

“Poorer, less developed states, it was argued, would have to do less by way of supervision because they lacked greater resources and capacity,” says Don Anton, who was legal counsel to the tribunal during the decision on behalf of the IUCN, the global conservation authority.

The tribunal, issuing a final court opinion the next year, disagreed. Each state that sponsored a deep-sea miner would be required to uphold the same standards of due diligence and measures that “ensure compliance.” Legal experts generally regarded the decision well, because it prevented contractors from seeking sponsorships with states that placed lower requirements on their activities. However, according to Anton, the decision meant that countries with limited budgets like Nauru have only two choices when they consider deep-sea mining: either sponsor a contractor entirely, or avoid the business altogether.

According to the tribunal’s decision, “you cannot excuse yourself as a sponsoring state by referring to your limited financial or administrative capacity,” says Isabel Feichtner, a law professor at the University of Würzburg in Germany. “And that of course raises the question: To what extent can a small developing state really control a contractor who might just have an office in that state?”

Nauru had just begun sponsoring a private company to explore the mineral riches at the bottom of the sea Clarion-Clipperton Zone. Nauru Ocean Resources Inc. (NORI), initially a subsidiary of Canada-based Nautilus Minerals, transferred its ownership to two Nauru foundations while the founder of Nautilus remained on NORI’s board. As a developing state, Nauru said, this kind of public-private partnership was the only way that it could join mineral exploration.

Nauru discussed the tribunal’s decision behind closed doors, according to a top official there at the time, and the government sought no independent consultation, hearing only guidance from Nautilus. Two months after the tribunal gave its opinion, Nauru officially agreed to sponsor NORI.

Control

After the tribunal’s decision, the European Union recognized that writing the world’s first deep-sea mining rules to govern companies thousands of miles away would be a tall order for countries with little capacity to conduct research.

The EU, whose member states also sponsor mining exploration, began in 2011 a 4.4 million euro ($5.1 million) project to help Pacific island states develop mining codes. However, by 2018, when most states had finished drafting national regulations, the Pacific Network on Globalization (PANG) found that the mining codes did “not sufficiently safeguard the rights of indigenous peoples or protect the environment in line with international law.” In addition, in some cases countries enacted legislation before civil society actors were aware that there was legislation, says PANG executive director Maureen Penjueli.

“In our region, most of our legislation assumes impact is very small, so there’s no reason to consult widely,” she says. “We found in most legislations is that it is assumed it’s only where mining takes place, not where impacts are felt.”

For Kara, mining laws are one thing, but enforcement is another. Sponsoring states must have “effective control” over the companies they sponsor, according to mineral exploration rules, but the ISA has not explicitly defined what that means. For example, the exploration contract for Tonga Offshore Mining Limited (TOML) says that if “control” changes, it must find a new sponsoring state. When DeepGreen acquired TOML in early 2020 after Nautilus filed for bankruptcy, the ISA said the Tongan government allowed the transfer and reevaluating the company’s background was not required.

Kara questions whether Tonga can adequately control TOML, its management, and its activities. TOML is registered in Tonga, but its management consists of Australian and Canadian employees of DeepGreen. It is owned by the Canadian company. Since DeepGreen acquired TOML, the only Tongan national in the company is no longer listed in a management role.

“It’s not enough to be incorporated in the sponsoring state. The sponsoring state must also be able to control the contractor and that raises the question as to the capacity to control,” Feichtner says.

When Kara’s Civil Society Forum of Tonga and others wrote to the ISA, they argued Canada should be the state sponsor of TOML, considering TOML is owned by a Canadian firm. In response, the ISA wrote that the Tongan government “has no objection” to the management changes, so no change was needed.

“Of all the work they’re doing in the area, I don’t know whether there’s any Tongan sitting there, doing the so-called validation and ascertaining what they do. We’re taking all of this at face value,” Kara says. With few resources to track down people who live in Canada or Australia, Kara is worried that Tonga will not be able to hold foreign individuals accountable for problems that may arise.

In merging with a U.S.-based company, DeepGreen became The Metals Company and will be responsible to shareholders in the U.S. The U.S., however, has not signed on to the U.N. convention that guides the ISA, and as such is not bound by ISA regulations, the only authority governing mining in the high seas.

“What I think is pretty clear is that ‘effective control’ means economic, not regulatory, control,” says Duncan Currie, a lawyer who advises conservation groups on ocean law. “So wherever it is, it’s not in Tonga.”

The risks

On Sept. 7, Tonga’s delegation to the IUCN’s global conservation summit in France joined 80% of government agencies that voted for a motion calling for a moratorium on deep-sea mining until more was known about the impacts and implications of policies.

“As a scientist, I am heartened by their decision,” says Douglas McCauley a professor of ocean science at the University of California, Santa Barbara. “The passage of this motion acknowledges research from scientists around the world showing that ocean mining is simply too risky a proposition for the planet and people.”

Tonga’s government continues to sponsor an exploration permit for TOML. According to the latest information, Tonga and TOML have agreed that the company will pay $1.25 in royalties for every ton of nodules mined. That may amount to just 0.16% of the value of the activities the country sponsors, according to scenarios presented to the ISA by a group from the Massachusetts Institute of Technology. Royalties paid to the ISA and then distributed to countries may be around $100,000.

Nauru’s contract with NORI stipulates that the company is not required to pay income tax. DeepGreen has reported in filings to the U.S. Securities and Exchange Commission that royalties will not be finalized until the ISA completes the exploitation code. With the two-year rule, NORI plans to apply for a mining permit, regardless of when the code is written.

“The only substantial economic benefit [Nauru] might derive is from royalty payments, and these are not even specified yet. and on the other hand, it potentially incurs this huge liability if something goes wrong,” Feichtner says.

Like NORI, TOML began its life as a subsidiary of Nautilus minerals, one of the world’s first deep-sea miners. Just before Nautilus’s project in Papua New Guinea’s waters failed and left the country $157 million in debt, its shareholders created DeepGreen.

“I am afraid that Tonga will be another Papua New Guinea,” Kara says. “If they start mining and something happens out there, we don’t have the resources, the expertise, because we need to validate what they’re doing.”

DeepGreen has said it is giving “developing” states like Tonga the opportunity to benefit from seabed mining without shouldering the commercial and technical risk. DeepGreen did not respond to Mongabay’s requests for comment.

“I’m still trying to figure out their angle. Personally, I think DeepGreen is using Pacific islanders to hype their image. I’m still thinking that we were never really the target. The shareholders have always been their target,” Kara says.

She says she doubts the minerals at the bottom of the ocean are needed for the world to transition away from fossil fuels. In a letter to a Tongan newspaper, Kara wrote, “Deep-sea mining is a relic, left over from the extractive economic approaches of the ’60s and ’70s. It has no place in this modern age of a sustainable blue economy. As Pacific Islanders already know — and science is just starting to learn — the deep ocean is connected to shallower waters and the coral reefs and lagoons. What happens in the deep doesn’t stay in the deep.”

![Electric Vehicles: Back to the Future? [Part 1/2]](https://dgrnewsservice.org/wp-content/uploads/sites/18/2021/11/Illustration_001_eddark.jpg)

by DGR News Service | Nov 20, 2021 | Biodiversity & Habitat Destruction, Climate Change, Mining & Drilling, The Problem: Civilization

By Frédéric Moreau

In memory of Stuart Scott

Each year while winter is coming, my compatriots, whom have already been told to turn off the tap when brushing their teeth, receive a letter from their electricity supplier urging them to turn down the heat and turn off unnecessary lights in case of a cold snap in order to prevent an overload of the grid and a possible blackout. At the same time the French government, appropriately taking on the role of advertiser for the national car manufacturers in which it holds shares¹, is promoting electric cars more and more actively. Even though electric vehicles (EV) have existed since the end of the 19th century (the very first EV prototype dates back to 1834).

They also plan to ban the sale of internal combustion engine cars as early as 2035, in accordance with European directives. Electric cars will, of course, have to be recharged, especially if you want to be able to turn on a very energy-consuming heater during cold spells.

The electric car, much-vaunted to be the solution to the limitation of CO2 emissions responsible for climate change, usually feeds debate and controversie focusing mainly on its autonomy. It depends on the on-board batteries and their recharging capacity, as well as the origin of the lithium in the batteries and the origin of their manufacture. But curiosity led me to be interested in all of the other aspects largely forgotten, very likely on purpose. Because the major problem, as we will see, is not so much the nature of the energy as it is the vehicle itself.

The technological changes that this change of energy implies are mainly motivated by a drop in conventional oil production which peaked in 2008 according to the IEA². Not by a recent awareness and sensitization to the protection of the environment that would suddenly make decision-makers righteous, altruistic and selfless. A drop that has so far been compensated for by oil from tar sands and hydraulic fracturing (shale oil). Indeed, the greenhouse effect has been known since 1820³, the role of CO2 in its amplification since 1856⁴ and the emission of this gas into the atmosphere by the combustion of petroleum-based fuels since the beginning of the automobile. As is the case with most of the pollutions of the environment, against which the populations have in fact never stopped fighting⁵, the public’s wishes are not often followed by the public authorities. The invention of the catalytic converter dates from 1898, but we had to wait for almost a century before seeing it adopted and generalized.

There are more than one billion private cars in the world (1.41 billion exactly when we include commercial vehicles and corporate SUV⁶), compared to 400 million in 1980. They are replaced after an average of 15 years. As far as electric cars are concerned, batteries still account for 30% of their cost. Battery lifespan, in terms of alteration of their charging capacity, which must not fall below a certain threshold, is on average 10 years⁷. However, this longevity can be severely compromised by intermittent use of the vehicle, systematic use of fast charging, heating, air conditioning and the driving style of the driver. It is therefore likely that at the end of this period owners might choose to replace the entire vehicle, which is at this stage highly depreciated, rather than just the batteries at the end of their life. This could cut the current replacement cycle by a third, much to the delight of manufacturers.

Of course, they are already promising much cheaper batteries with a life expectancy of 20 years or even more, fitted to vehicles designed to travel a million kilometers (actually just like some old models of thermal cars). In other words, the end of obsolescence, whether planned or not. But should we really take the word of these manufacturers, who are often the same ones who did not hesitate to falsify the real emissions of their vehicles as revealed by the dieselgate scandal⁸? One has the right to be seriously skeptical. In any case, the emergence of India and China (28 million new cars sold in 2016 in the Middle Kingdom) is contributing to a steady increase in the number of cars on the road. In Beijing alone, there were 1,500 new registrations per day in 2009. And now with the introduction of quotas the wait for a car registration can be up to eight years.

For the moment, while billions of potential drivers are still waiting impatiently, it is a question of building more than one billion private cars every fifteen years, each weighing between 800 kilos and 2.5 tons. The European average being around 1.4 tons or 2 tons in the United States. This means that at the beginning of the supply chain, about 15 tons of raw materials are needed for each car⁹. Though it is certainly much more if we include the ores needed to extract rare earths. In 2050, at the current rate of increase, we should see more than twice as many cars. These would then be replaced perhaps every ten years, compared with fifteen today. The raw materials must first be extracted before being transformed. Excavators, dumpers (mining trucks weighing more than 600 tons when loaded for the CAT 797F) and other construction equipment, which also had to be built first, run on diesel or even heavy oil (bunker) fuel. Then the ores have to be crushed and purified, using at least 200 m³ of water per ton in the case of rare earths¹⁰. An electric car contains between 9 and 11 kilos of rare earths, depending on the metal and its processing. Between 8 and 1,200 tons of raw ore must be extracted and refined to finally obtain a single kilo¹¹. The various ores, spread around the world by the vagaries of geology, must also be transported to other processing sites. First by trucks running on diesel, then by bulk carriers (cargo ships) running on bunker fuel, step up from coal, which 100% of commercial maritime transport uses, then also include heavy port infrastructures.

A car is an assembly of tens of thousands of parts, including a body and many other metal parts. It is therefore not possible, after the necessary mining, to bypass the steel industry. Steel production requires twice as much coal because part of it is first transformed into coke in furnaces heated from 1,000°C to 1,250°C for 12 to 36 hours, for the ton of iron ore required. The coke is then mixed with a flux (chalk) in blast furnaces heated from 1800 to 2000°C¹². Since car makers use sophisticated alloys it is often not possible to recover the initial qualities and properties after remelting. Nor to separate the constituent elements, except sometimes at the cost of an energy expenditure so prohibitive as to make the operation totally unjustified. For this reason the alloyed steels (a good dozen different alloys) that make up a car are most often recycled into concrete reinforcing bars¹³, rather than into new bodies as we would like to believe, in a virtuous recycling, that would also be energy expenditure free.

To use an analogy, it is not possible to “de-cook” a cake to recover the ingredients (eggs, flour, sugar, butter, milk, etc.) in their original state. Around 1950, “the energy consumption of motorized mobility consumed […] more than half of the world’s oil production and a quarter of that of coal¹⁴”. As for aluminum, if it is much more expensive than steel, it is mainly because it is also much more energy-intensive. The manufacturing process from bauxite, in addition to being infinitely more polluting, requires three times more energy than steel¹⁵. It is therefore a major emitter of CO2. Glass is also energy-intensive, melting at between 1,400°C and 1,600°C and a car contains about 40 kg of it¹⁶.

Top: Coal mine children workers, Pennsylvania, USA, 1911. Photo: Lewis WICKES HINE, CORBIS

Middle left to right: Datong coal mine, China, 2015. Photo: Greg BAKER, AFP. Graphite miner, China.

Bottom: Benxi steelmaking factory, China.

A car also uses metals for paints (pigments) and varnishes. Which again means mining upstream and chemical industry downstream. Plastics and composites, for which 375 liters of oil are required to manufacture the 250kg incorporated on average in each car, are difficult if not impossible to recycle. Just like wind turbine blades, another production of petrochemicals, which are sometimes simply buried in some countries when they are dismantled¹⁷. Some plastics can only be recycled once, such as PET bottles turned into lawn chairs or sweaters, which are then turned into… nothing¹⁸. Oil is also used for tires. Each of which, including the spare, requires 27 liters for a typical city car, over 100 liters for a truck tire.

Copper is needed for wiring and windings, as an electric car consumes four times as much copper as a combustion engine car. Copper extraction is not only polluting, especially since it is often combined with other toxic metals such as cadmium, lead, arsenic and so on, it is also particularly destructive. It is in terms of mountain top removal mining, for instance, as well as being extremely demanding in terms of water. Chile’s Chuquicamata open-pit mine provided 27.5% of the world’s copper production and consumed 516 million m³ of water for this purpose in 2018¹⁹. Water that had to be pumped, and above all transported, in situ in an incessant traffic of tanker trucks, while the aquifer beneath the Atacama desert is being depleted. The local populations are often deprived of water, which is monopolized by the mining industry (or, in some places, by Coca-Cola). They discharge it, contaminated by the chemicals used during refining operations, to poisoned tailings or to evaporate in settling ponds²⁰. The inhumane conditions of extraction and refining, as in the case of graphite in China²¹, where depletion now causes it to be imported from Mozambique, or of cobalt and coltan in Congo, have been regularly denounced by organizations such as UNICEF and Amnesty International²².

Dumper and Chuquicamata open-pit copper mine, Chile – Photo: Cristóbal Olivares/Bloomberg

And, of course, lithium is used for the batteries of electric cars, up to 70% of which is concentrated in the Andean highlands (Bolivia, Chile and Argentina), and in Australia and China. The latter produces 90% of the rare earths, thus causing a strategic dependence which limits the possibility of claims concerning human rights. China is now eyeing up the rare earths in Afghanistan, a country not particularly renowned for its rainfall, which favors refining them without impacting the population. China probably doesn’t mind negotiating with the Taliban, who are taking over after the departure of American troops. The issue of battery recycling has already been addressed many times. Not only is it still much cheaper to manufacture new ones, with the price of lithium currently representing less than 1% of the final price of the battery²³, but recycling them can be a new source of pollution, as well as being a major energy consumer²⁴.

This is a broad outline of what is behind the construction of cars. Each of which generates 12-20 tons of CO2 according to various studies, regardless of the energy — oil, electricity, cow dung or even plain water — with which they are supposed to be built. They are dependent on huge mining and oil extraction industries, including oil sands and fracking as well as the steel and chemical industries, countless related secondary industries (i.e. equipment manufacturers) and many unlisted externalities (insurers, bankers, etc.). This requires a continuous international flow of materials via land and sea transport, even air freight for certain semi-finished products, plus all the infrastructures and equipment that this implies and their production. All this is closely interwoven and interdependent, so that they finally take the final form that we know in the factories of car manufacturers, some of whom do not hesitate to relocate this final phase in order to increase their profit margin. It should be remembered here that all these industries are above all “profit-making companies”. We can see this legal and administrative defining of their raison d’être and their motivation. We too often forget that even if they sometimes express ideas that seem to meet the environmental concerns of a part of the general public, the environment is a “promising niche”, into which many startups are also rushing. They only do so if they are in one way or another furthering their economic interests.

Once they leave the factories all these cars, which are supposed to be “clean” electric models, must have roads to drive on. There is no shortage of them in France, a country with one of the densest road networks in the world, with more than one million kilometers of roads covering 1.2% of the country²⁵. This makes it possible to understand why this fragmentation of the territory, a natural habitat for animal species other than our own, is a major contributor to the dramatic drop in biodiversity, which is so much to be deplored.

Top: Construction of a several lanes highway bridge.

Bottom left: Los Angeles, USA. Bottom right: Huangjuewan interchange, China.

At the global level, there are 36 million kilometers of roads and nearly 700,000 additional kilometers built every year ²⁶. Roads on which 100 million tons of bitumen (a petroleum product) are spread²⁷, as well as part of the 4.1 billion tons of cement produced annually²⁸. This contributes up to 8% of the carbon dioxide emitted, at a rate of one ton of this gas per ton of cement produced in the world on average²⁹, even if some people in France pride themselves on making “clean” cement³⁰, which is mixed with sand in order to make concrete. Michèle Constantini, from the magazine Le Point, reminds us in an article dated September 16, 2019, that 40-50 billion tons of marine and river sand (i.e. a cube of about 3 km on a side for an average density of 1.6 tons/m3) are extracted each year³¹.

This material is becoming increasingly scarce, as land-based sand eroded by winds is unsuitable for this purpose. A far from negligible part of these billions of tons of concrete, a destructive material if ever there was one³², is used not only for the construction of roads and freeways, but also for all other related infrastructures: bridges, tunnels, interchanges, freeway service areas, parking lots, garages, technical control centers, service stations and car washes, and all those more or less directly linked to motorized mobility. In France, this means that the surface area covered by the road network as a whole soars to 3%, or 16,500 km². The current pace of development, all uses combined, is equivalent to the surface area of one and a half departments per decade. While metropolitan France is already artificialized at between 5.6% and 9.3% depending on the methodologies used (the European CORINE Land Cover (CLC), or the French Teruti-Lucas 2014)³³, i.e. between 30,800 km² and 51,150 km², respectively, the latter figure which can be represented on this map of France by a square with a side of 226 km. Producing a sterilized soil surface making it very difficult to return it later to other uses. Land from which the wild fauna is of course irremediably driven out and the flora destroyed.

In terms of micro-particle pollution, the electric car also does much less well than the internal combustion engine car because, as we have seen, it is much heavier. This puts even more strain on the brake pads and increases tire wear. Here again, the supporters of the electric car will invoke the undeniable efficiency of its engine brake. Whereas city driving, the preferred domain of the electric car in view of its limited autonomy which makes it shun the main roads for long distances, hardly favors the necessary anticipation of its use. An engine brake could be widely used for thermal vehicles, especially diesel, but this is obviously not the case except for some rare drivers.

A recent study published in March 2020 by Emissions Analytics³⁴ shows that micro-particle pollution is up to a thousand times worse than the one caused by exhaust gases, which is now much better controlled. This wear and tear, combined with the wear and tear of the road surface itself, generates 850,000 tons of micro-particles, many of which end up in the oceans³⁵. This quantity will rise to 1.3 million tons by 2030 if traffic continues to increase³⁶. The false good idea of the hybrid car, which is supposed to ensure the transition from thermal to electric power by combining the two engines, is making vehicles even heavier. A weight reaching two tons or more in Europe, and the craze for SUVs will further aggravate the problem.

When we talk about motorized mobility, we need to talk about the energy that makes it possible, on which everyone focuses almost exclusively. A comparison between the two sources of energy, fossil fuels and electricity, is necessary. French electricity production was 537 TWh in 2018³⁷. And it can be compared to the amount that would be needed to run all the vehicles on the road in 2050. By then, the last combustion engine car sold at the end of 2034 will have exhaled its last CO2-laden breath. Once we convert the amount of road fuels consumed annually, a little over 50 billion liters in 2018, into their electrical energy equivalent (each liter of fuel is able to produce 10 kWh), we realize that road fuels have about the same energy potential as that provided by our current electrical production. It is higher than national consumption, with the 12% surplus being exported to neighboring countries. This means a priori that it would be necessary to double this production (in reality to increase it “only” by 50%) to substitute electricity for oil in the entire road fleet… while claiming to reduce by 50% the electricity provided by nuclear power plants³⁸.

Obviously, proponents of the electric car, at this stage still supposed to be clean if they have not paid attention while reading the above, will be indignant by recalling, with good reason, that its theoretical efficiency, i.e. the part of consumed energy actually transformed into mechanical energy driving the wheels, is much higher than that of a car with a combustion engine: 70% (once we have subtracted, from the 90% generally claimed, the losses, far from negligible, caused by charging the batteries and upstream all along the network between the power station that produces the electricity and the recharging station) against 40%. But this is forgetting a little too quickly that the energy required that the mass of a car loaded with batteries, which weigh 300-800 kg depending on the model, is at equal performance and comfort, a good third higher than that of a thermal car.