by DGR News Service | Jul 24, 2014 | Indigenous Autonomy, White Supremacy

Photo Credit: David Clow

By Will Falk / Deep Green Resistance

Each night Unist’ot’en Clan spokeswoman, Freda Huson, and her husband Wet’suwet’en hereditary chief Toghestiy fall asleep on their traditional land not knowing whether the Royal Canadian Mounted Police are going to storm their bridge in the depths of night.

Each winter, when Freda and Toghestiy ride their snowmobiles down forestry roads to bring in supplies, to hunt, or to check their traplines, they don’t know whether they will find piles of felled trees maliciously dragged across their paths.

Each time Freda and Toghestiy leave their territory for a few days they don’t know if they will return to find another attack in an old tradition of cowardly arson perpetrated by hostile settlers on Wet’suwet’en territories leaving smoking embers where their cabin once stood.

I ponder this as I sit in a workshop with other settlers during the 6-day Unist’ot’en Action Camp – a series of workshops hosted on the traditional territories of the Unist’ot’en Clan of the Wet’suwet’en Nation to promote strategic planning and co-ordination in the struggle against the spread of fossil fuel pipelines. This particular workshop is designed as a discussion to promote understanding about how settlers can work in better solidarity with indigenous peoples struggling to protect their homes and carrying out their responsibilities to the land.

Most of the ideas discussed revolve around decolonizing our hearts and minds to learn to see the role non-indigenous peoples are playing in the genocidal processes threatening the survival of indigenous peoples. Some of the ideas involve material support for indigenous peoples engaged in front line resistance like the Unist’ot’en. A few even suggest that settlers become physically present next to indigenous peoples on the front lines.

But, I am troubled. We have skipped something. What exactly do we mean by “solidarity?”

***

A common scene from my life as a public defender shows me – a white man in a suit and tie – sitting next to a shackled African, Chicana, or indigenous mother in a courtroom. In front of us sits a judge – an older white man in black robes. Across from us sits the prosecutor – another white man in a suit. Directly behind us, where he is felt more than seen, stands a big white man in the brown uniform of a sheriff’s deputy. He has a gun on one hip, a taser on the other, and the keys to my client’s shackles on a loop on his belt.

My client stares at the judge in a mix of horror and hatred as she is sentenced to prison for stealing from a supermarket to support her children or for lying to a police officer about her name because she had outstanding parking tickets and had to get the kids to school or for punching a cop when the latest in a long list of arbitrary stops by police officers finally caused something inside of her to snap.

As the judge announces how many days in jail my client will be spending, she reaches for my arm with tears in her eyes and asks, “Mr. Falk, won’t you do something?”

I cannot meet her gaze. I tell myself there’s nothing I can do. There’s no argument I can make to sway the judge. There’s no way to stop the sheriff’s deputy behind us from leading my client back down the long concrete tunnel connecting the courthouse and the city jail.

I try to comfort myself. What does she want me to do? Yell at the judge? Tackle the deputy? Spit on the prosecutor for his role in sending this mother to jail?

***

We gathered to sit on wooden benches arranged in a half-circle on a hot and sunny morning during the Unist’ot’en Action Camp to listen to two indigenous men speak about their experiences on the front lines of resistance. Each man had been shot at by police and soldiers, each man had served time in jail, and each man received utter respect from each individual listening.

The first man faced 7,7000 rounds fired by the RCMP at the Gustafsen Lake Stand-off in 1995 when a group of Original Peoples occupied a sacred site on a cattle ranch on unceded Canoe Creek First Nation land because the rancher tried to prevent their ceremonies. For his part at Gustafsen Lake, he was sentenced to five years in prison. During the Oka Crisis in 1990 when the town of Oka, Quebec sought to build a golf course over a Mohawk burial ground, the second man and his comrades blockaded several small British Columbian towns shutting down their local economies. He, too, was convicted and spent time in jail for his actions.

The second man said the blockades were carried out “in solidarity” with the resisters at Oka. This was the only time either of the men mentioned the word “solidarity.” They spoke of supporting resistance, praying for resistance, and helping with ceremonies. But, it was only when engaged in actions where co-resisters placed themselves in similarly dangerous situations that the term “solidarity” was used.

***

I got back from Unist’ot’en Camp earlier this afternoon and checked my email for the first time in days. My inbox was inundated by emails from various list serves proclaiming “Solidarity with Palestine!”

Meanwhile, in Gaza, occupying Israeli bulldozers are demolishing the homes of Palestinian families with suspected ties to Hamas while colonial Israeli bombs are indiscriminately falling on men, women, and children adding to the pile of dead numbered at well over 500 corpses and counting.

“That’s terrible, Will,” you may be thinking. “But what do you want me to do about it?”

Put yourself in Gaza right now. Dig a pit in your back yard, turn your ear anxiously to the sky, and keep the path to your back door clear, so that when you hear the hum of jets overhead you can sprint to your makeshift bomb shelter.

Look down the street for bull-dozers. When you spot one, grab the nearest bag in a panic, shove as much food into it as possible, scramble for some clean underwear, find your toothbrush, and sprint out the door without a look back for the nearest safe space.

Stand over the broken corpses of your children in the pile of dust and ashes that used to be their bedroom. Moan. Weep. Wail. When you wake up for the first time without crying, feel the anger burn through your chest and down your arms into your clinched fists. Ask yourself what you should do next.

Ask yourself: What does solidarity look like?

***

Maybe there really was nothing I could do to stop my clients from being hauled to jail in those courtrooms of my past. Unfortunately, I tried not to think about it too much. Placing myself in that vulnerable of a situation was too scary for me. If I argued too strongly, too fervently the judge could fine me. If I yelled at the prosecutor I could be held in contempt of court. If I spit on him, I certainly would be held in contempt of court. If I tried to stop the deputy, I would be tasered and taken to jail. I might even be shot during the scuffle and killed.

The truth is indigenous and other resisters are being dragged to jail, tasered, and even shot and killed every day on the front lines. And, they’ve been on the front lines for a very long time. I’ve realized that freedom from the vulnerabilities frontline resisters experience is a privilege and the maintenance of this privilege is leaving resisters isolated on front lines around the world.

It is time we understand exactly what solidarity looks like. Solidarity looks like the possibility of prison time. Solidarity looks like facing bullets and bombs. Solidarity looks like risking mental, spiritual, and physical health. Solidarity looks like placing our bodies on the front lines – strong shoulder to strong shoulder – next to our brothers and sisters who are already working so courageously to stop the destruction of the world.

Browse Will Falk’s Unis’tot’en Camp series at the Deep Green Resistance Blog

by DGR News Service | Jul 19, 2014 | Gender, Women & Radical Feminism

Deep Green Resistance condemns in the strongest possible terms the decision of Monkeywrench Books in Austin, Texas to cut ties with activist Robert Jensen. Robert has received a massive amount of criticism recently for his article “Some Basic Propositions About Sex, Gender and Patriarchy”, in which he makes public his support for women. That so many have been quick to turn on a seasoned activist for the crime of saying that females exist is not surprising; the women of DGR, like thousands of radical women throughout history, know all too well the threats, insults, denunciations, and other abuse that comes to those who question the genderist ideology and stand with women in the fight for liberation from male violence.

Deep Green Resistance would like to publicly thank Robert Jensen for his activism and offer our support in this trying time. In a world where so-called “radical” communities are blacklisting actually radical women at a breakneck pace – while pedophile rapists like Hakim Bey and misogynists like Bob Black are welcomed with open arms – Robert has been a uniquely positive exception to the Left’s legacy of woman-hating. His contributions to the discussion around radical opposition to pornography, prostitution, and other forms of violence are especially valuable. DGR would like to acknowledge Robert’s efforts as a model for male solidarity work and offer our full support. The men of DGR specifically would like to extend a thanks to Robert for his huge influence in many of their lives.

by DGR News Service | Jun 21, 2014 | Gender, Repression at Home

By Max Wilbert / Deep Green Resistance

Despite the seeming popularity of environmental and social justice work in the modern world, we’re not winning. We’re losing. In fact, we’re losing really badly. [1]

Why is that?

One reason is because few popular strategies pose real threats to power. That’s not an accident: the rules of social change have been clearly defined by those in power. Either you play by the rules — rules which don’t allow you to win — or you break free of the rules, and face the consequences.

Play By The Rules, or Raise the Stakes

We all know the rules: you’re allowed to vote for either one capitalist or the other, vote with your dollars,[2] write petitions (you really should sign this one), you can shop at local businesses, you can eat organic food (if you can afford it), and you can do all kinds of great things!

But if you step outside the box of acceptable activism, you’re asking for trouble. At best, you’ll face ridicule and scorn. But the real heat is reserved for movements that pose real threats. Whether broad-based people’s movements like Occupy or more focused revolutionary threats like the Black Panthers, threats to power break the most important rule they want us to follow: never fight back.

State Tactic #1: Overt Repression

Fighting back – indeed, any real resistance – is sacrilegious to those in power. Their response is often straightforward: a dozen cops slam you to the ground and cuff you; “less-lethal” weapons cover the advance of a line of riot police; the sharp report of SWAT team’s bullets.

This type of overt repression is brutally effective. When faced with jail, serious injury, or even death, most don’t have the courage and the strategy to go on. As we have seen, state violence can behead a movement.

That was the case with Fred Hampton, an up-and-coming Black Panther Party leader in Chicago, Illinois. A talented organizer, Hampton made significant gains for the Panthers in Chicago, working to end violence between rival (mostly black) gangs and building revolutionary alliances with groups like the Young Lords, Students for A Democratic Society, and the Brown Berets. He also contributed to community education work and to the Panther’s free breakfast program.

These activities could not be tolerated by those in power: they knew that a charismatic, strategic thinker like Hampton could be the nucleus of revolution. So, they decided to murder him. On December 4, 1969, an FBI snitch slipped Hampton a sedative. Chicago police and FBI agents entered his home, shot and killed the guard, Mark Clark, and entered Hampton’s room. The cops fired two shots directly into his head as he lay unconscious. He was 21 years old.

The Occupy Movement, at its height, posed a threat to power by making the realities of mass anti-capitalism and discontent visible, and by providing physical focal points for the dissent that spawns revolution. While Occupy had some issues (such as the difficulties of consensus decision-making and generally poor responses to abusive behavior inside camps), the movement was dynamic. It claimed physical space for the messy work of revolution to happen, and represented the locus of a true threat.

The response was predictable: the media assaulted relentlessly, businesses led efforts to change local laws and outlaw encampments, and riot police were called in as the knockout punch. It was a devastating flurry of blows, and the movement hasn’t yet recovered. (Although many of the lessons learned at Occupy may serve us well in the coming years).

State Tactic #2: Covert Repression

Violent repression is glaring. It gets covered in the news, and you can see it on the streets. But other times, repression isn’t so obvious. A recent leaked document from the private security and corporate intelligence firm Strategic Forecasting, Inc. (better known as STRATFOR) contained this illustrative statement:

Most authorities will tolerate a certain amount of activism because it is seen as a way to let off steam. They appease the protesters by letting them think that they are making a difference — as long as the protesters do not pose a threat. But as protest movements grow, authorities will act more aggressively to neutralize the organizers.

The key word is neutralize: it represents a more sophisticated strategy on behalf of power, a set of tactics more insidious than brute force.

Most of us have probably heard about COINTELPRO (shorthand for Counter-Intelligence Program), a covert FBI program officially underway between 1956 and 1971. COINTELPRO mainly targeted socialists and communists, black nationalists, Civil Rights groups, the American Indian Movement, and much of the left, from Quakers to Weathermen. The FBI used four main techniques to undermine, discredit, eliminate, and otherwise neutralize these threats:

- Force

- Harassment (subpoenas, false accusations, discriminatory enforcement of taxation, etc.)

- Infiltration

- Psychological warfare

How can we become resilient to these threats? Perhaps the first step is to understand them; to internalize the consequences of the tactics being used against us.

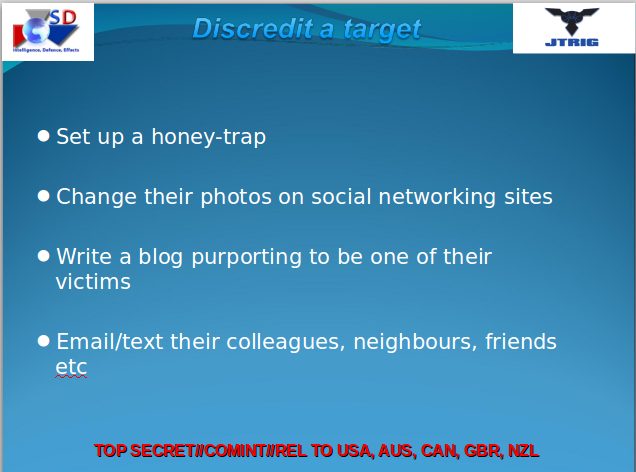

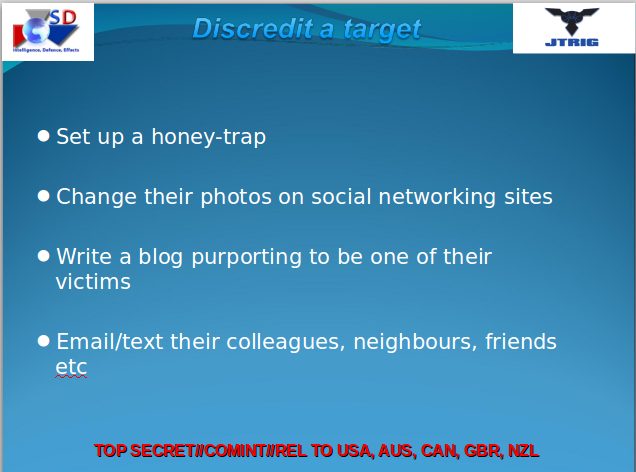

The JTRIG Leaks

On February 24 of this year, Glenn Greenwald released an article detailing a secret National Security Agency (NSA) unit called JTRIG (Joint Threat Research Intelligence Group). The article, which sheds new light on the tactics used to suppress social movements and threats to power, is worth quoting at length:

Among the core self-identified purposes of JTRIG are two tactics: (1) to inject all sorts of false material onto the internet in order to destroy the reputation of its targets; and (2) to use social sciences and other techniques to manipulate online discourse and activism to generate outcomes it considers desirable. To see how extremist these programs are, just consider the tactics they boast of using to achieve those ends: “false flag operations” (posting material to the internet and falsely attributing it to someone else), fake victim blog posts (pretending to be a victim of the individual whose reputation they want to destroy), and posting “negative information” on various forums.

It shouldn’t come as a total surprise that those in power use lies, manipulation, false information, fake identities, and “manipulation [of] online discourse” to further their ends. They always fight dirty; it’s what they do. They never fight fair, they can never allow truth to be shown, because to do so would expose their own weakness.

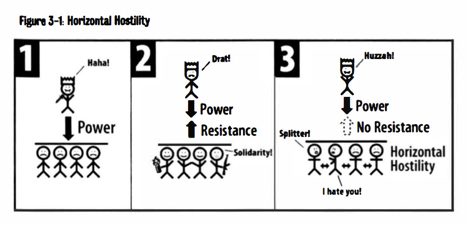

As shown by COINTELPRO, this type of operation is highly effective at neutralizing threats. Snitchjacketing and divisive movement tactics were used widely during the COINTELPRO era, and encouraged activists to break ties, create rivalries, and vie against one another. In many cases, it even led to violence: prominent, good hearted activists would be labeled “snitches” by agents, and would be isolated, shunned, and even killed.

As a friend put it,

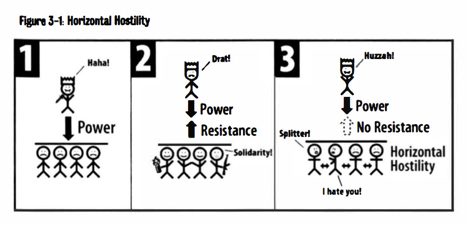

“By encouraging horizontal, crowdsourced repression, activists’ focus is shifted safely away from those in power and towards each other.”

Are Activists Targeted?

Some organizations have ideas so revolutionary, so incendiary that they pose a threat all by themselves, simply by existing.

Deep Green Resistance is such a group. If these tactics are being used to neutralize activist groups, then Deep Green Resistance (DGR) seems a prime target. Proudly Luddite in character, DGR believes that the industrial way of life, the soil-destroying process known as agriculture, and the social system called civilization are literally killing the planet – at the rate of 200 species extinctions, 30 million trees, and 100 million tons of CO2 every day. With numbers like that, time is short.

With two key pieces of knowledge, the DGR strategy comes into focus. The first is that global industrial civilization will inevitably collapse under the weight of its own destructiveness. The second is that this collapse isn’t coming soon enough: life on Earth could very well be doomed by the time this collapse stops the accelerating destruction.

With these understandings, DGR advocates for a strategy to pro-actively dismantle industrial civilization. The strategy (which acknowledges that resisters will face fierce opposition from governments, corporations, and those who cling to modern life) calls for direct attacks on critical infrastructure – electric grids, fossil fuel networks, communications, etc. – with one goal: to shut down the global industrial economy. Permanently.

The strategy of direct attacks on infrastructure has been used in countless wars, uprisings, and conflicts because it is extremely effective. The same strategies are taught at military schools and training camps around the planet, and it is for this reason – an effective strategy – that DGR poses a real and serious threat to power. Of course, writing openly about such activities and then taking part in them would be stupid, which is why DGR is an “aboveground” organization. Our work is limited to building a culture of resistance (which is no easy feat: our work spans the range of activities from non-violent resistance to educational campaigns, community organizing, and building alternative systems) and spreading the strategies that we advocate in the hope that clandestine networks can pull off the dirty work in secret.

When I speak to veterans – hard-jawed ex-special forces guys – they say the strategy is good. It’s a real threat.

Threat Met With Backlash

That threat has not gone unanswered. In a somewhat unsurprising twist, given the information we’ve gone over already, DGR’s greatest challenges have not come from the government, at least not overtly. Instead, the biggest challenges have come from radical environmentalists and social justice activists: from those we would expect to be among our supporters and allies. The focal point of the controversy? Gender.

The conflict has a long history and deserves a few hours of discussion and reading, but here is the short version: DGR holds that female-only spaces should be reserved for females. This offends many who believe that male-born individuals (who later come to identify as female) should be allowed access to these spaces. It’s all part of a broader, ongoing disagreement between gender abolitionists (like DGR and others), who see gender as the cultural lattice of women’s oppression, and those who view gender as an identity that is beyond criticism.

(To learn more about the conflict, view Rachel Ivey’s presentation entitled The End of Gender.)

Due to this position, our organization has been blacklisted from speaking at various venues, our organizers have received threats of violence (often sexualized), and our participation in a number of struggles has been blocked – at the expense of the cause at hand.

A Case Study in JTRIG?

Much of the anti-DGR rhetoric has been extraordinary, not for passionate political disagreement, but for misinformation and what appears to be COINTELPRO-style divisiveness. Are we the victims of a JTRIG-style smear campaign?

On February 23 of this year, the Earth First! Newswire released an anonymous article attacking Deep Green Resistance. The main subject of the article was the ongoing debate over gender issues.

(Although perhaps debate is the wrong word in this case: Earth First! Newswire has published half a dozen vitriolic pieces attacking DGR. They seem to have an obsession. On the other hand, DGR has never used organizational resources or platforms to publish a negative comment about Earth First.)

Here are a few of the fabrications contained in the February 23 article:

- “Keith and Jensen [DGR co-founders] do not recognize the validity of traditionally marginalized struggles [like] Black Power.” (a wild, false claim, given the long and public history of anti-racist work and solidarity by those two. [3])

- DGR members have “outed” transgender people by posting naked photos of them. (Completely false not to mention obscene and offensive.[4])

- DGR is “allied with” gay-to-straight conversion camps. (The lies get ever more absurd. DGR has countless lesbian and gay members, including founding members. Lesbian and gay members are involved at every level of decision making in DGR.)

- DGR requires “genital checks” for new members. (I can’t believe we even have to address this – it’s a surreal accusation. It is, of course, a lie.)

If these claims weren’t so serious, they would be laughable. But lies like this are no laughing matter.

Here is one illustrative list of tactics from the JTRIG leaks:

“Crowdsourced Repression”

The timing of these events – the Earth First! Newswire article followed the very next day by Greenwald’s JTRIG article – is ironic. Of course, it made me think: are we the victims of a JTRIG-style character assassination? Or am I drawing conclusions where there are none to be drawn?

The campaigns against DGR do have many of the hallmarks of COINTELPRO-style repression. They are built on a foundation of political differences magnified into divisive hatred through paranoia and the spread of hearsay. In the 1960s and 70s, techniques that seem similar were used to create divisions within groups like the Black Panthers and the American Indian Movement.

Ultimately, these movements tore themselves apart in violence and suspicion; the powerful were laughing all the way to the bank. In many cases, we don’t even know if the FBI was involved; what is certain is that the FBI-style tactics – snitchjacketing, rumormongering, the sowing of division and hatred – were being adopted by paranoid activists.

In some ways, the truth doesn’t really matter. Whether these activists were working for the state or not, they served to destroy movements, alliances, and friendships that took decades or generations to build.

I’ll be clear: I don’t mean to claim that the “Letter Collective” (as the anonymous authors of the February 23 article named themselves) are agents of the state. To do so would be a violation of security culture. [5] Modern activists seem to have largely forgotten the lessons of COINTELPRO, and I am wary of forgetting those lessons myself. Snitchjacketing is a bad behavior, and we should have no tolerance for it unless there is substantive evidence.

But members of the “Letter Collective”, at the very least, have violated security culture by spreading rumors and unsubstantiated claims of serious misconduct. Good security culture practices preclude this behavior. In the face of JTRIG and the modern surveillance and repression state, careful validation of serious claims is the least that activists can do. Didn’t we learn this lesson in the 60s?

Divide and Conquer

By itself, verifying rumors before spreading them is a poor defense against the repression modern activists face. Instead, we must challenge divisiveness itself: one of the biggest threats to our success.

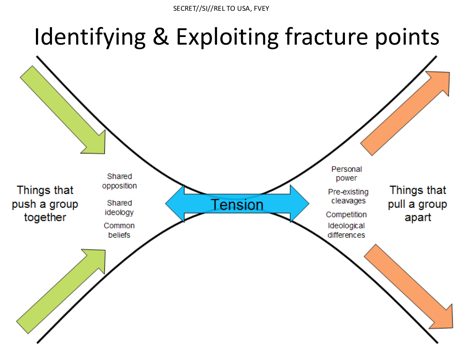

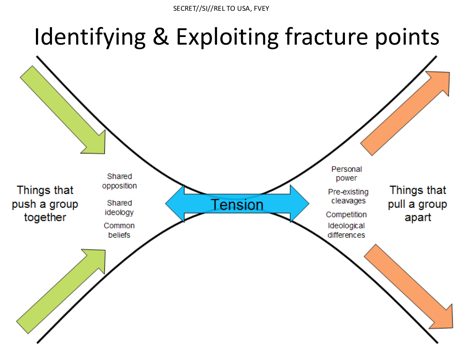

The 2011 STRATFOR leak included information about corporate strategies to neutralize activist and community movements. Essentially, STRATFOR advocates dividing movements into four character types: radicals, idealists, realists, and opportunists. These camps can then be dealt with summarily:

First, isolate the radicals. Second, “cultivate” the idealists and “educate” them into becoming realists. And finally, co-opt the realists into agreeing with industry. [6]

This is how movements are neutralized: those who should be allies are divided, infighting becomes rampant, and paranoia rules the roost. To combat these strategies, we must understand the danger they represent and how to counter them.

Fight Repression With Solidarity

We all want to win. We want to end capitalism, reverse ecological collapse, and build a culture in which social justice is fundamental. Many of us have different specific goals or strategies, but we must find similarities, overlaps, and areas where we can work together.

As Bob Ages, commenting on STRATFOR’s divide-and-conquer tactics, put it in a recent piece:

“Our response has to be the opposite; bridging divides, foster mutual understanding and solidarity, stand together come hell or high water.”

Many people across the left share 80% or more of their politics, and yet constructive criticism and mature discussion of disagreements is the exception, not the rule. We need more thoughtful behavior. Don’t spread rumors, don’t tear down other activists, and don’t forget who the real enemy is. Don’t waste your time fighting those who should be your allies – even if they are only partial allies. Let’s disagree, and let our disagreements help us learn more from each other and build alliances.

In the end, that’s our only chance of winning: together.

References

Max Wilbert lives in the Pacific Northwest, where he works to support indigenous resistance to industrial extraction projects, anti-racist initiatives, and radical feminist struggles as part of Deep Green Resistance. He makes his living as a writer and photographer, and can be contacted at max@maxwilbert.org.

From Dissident Voice

by DGR News Service | Jun 17, 2014 | Indigenous Autonomy, Mining & Drilling

Deep Green Resistance is dedicated to the fight against industrial civilization and its legacy of racism, patriarchy, and colonialism. For this reason, DGR would like to publicly state its support for the Oglala Lakota in their current fight against the genocidal mining operations of the Cameco Corporation.

Cameco is currently attempting to expand its already illegal resource extraction campaign despite undeniable evidence that their abuse of the Earth is leading to increased rates of cancer, diabetes, and other life-threatening illnesses among the Lakota people.

The only acceptable action on the part of the Cameco Corporation is immediate cessation of any and all mining activities in the ancestral home of the Lakota people; anything else will be met with resistance, and DGR will lend whatever support it can to those on the front lines.

The indigenous peoples of this land have always been at the forefront of the struggle against the dominant culture’s ecocidal violence, and DGR would like to offer its support and encouragement to Debra White Plume, the Lakota activist group Owe Aku, and all other indigenous women and men fighting for the future of the planet. The time for resistance is long past, and we are thankful every day that the Earth has warriors like the Oglala Lakota fighting in its defense.

For more information, please visit Owe Aku International at http://oweakuinternational.org/

by DGR News Service | Jun 17, 2014 | Biodiversity & Habitat Destruction, Indigenous Autonomy

Deep Green Resistance stands in sympathy and solidarity with Don Celestino Bartolo and the farmers and residents of the municipality of Juchitan de Zaragoza as well as all those who live on the Isthmus of Tehuantepec, as they suffer and resist Gas Natural Fenosa’s Biío Hioxo Wind Energy project. Like most large infrastructure projects, the Biío Hioxo Energy project ignores how indigenous communities use the land for food, sacred places, and community integrity. This project harms the land by destroying soils, forests, and natural spaces, as well as with noise and visual pollution.

Projects like this threaten the way of life of the residents of Juchitan de Zaragoza and the Isthmus of Tehuantepec, and destroy the land. It is typical of the destructiveness of civilization and the unbridled greed of capitalism. Biío Hioxo Energy also serves as an object lesson in the folly of green technology, and deserves our condemnation and resistance.

Indigenous peoples have always been at the forefront of the struggle against the dominant culture’s ecocidal violence. We are heartened by the strength of the people of Tehuantepec, who are resisting with strength and desperation. DGR offers its support and encouragement to those on the front lines of the fight to save the planet, and despite our lack of experience and membership in the region we will support the struggle in whatever way we can.

For more information on the Biío Hioxo project, see http://www.cipamericas.org/archives/12042

by DGR News Service | Jun 4, 2014 | Alienation & Mental Health

By Susan Hyatt and Michael Carter, DGR Southwest Coalition

This article is the third part of a series on mental health. You can read the first piece: “An Inhuman System” and the second: “Mental Illness as a Social Construct”.

What was my drink

My delicious addiction

That led to my oppression?

My drug of choice

I held in my hand

Was a glassful of depression.

—Carol Ann F., Vashon Island, Washington

If you watched any commercial television in the early 1990s, you may remember the Old Milwaukee beer ad featuring pleased men relaxing with a couple sixpacks, agreeing that “It doesn’t get any better than this.” Advertising has a way of being more effective the more farfetched it becomes, by way of memorable slogans and images rather than accuracy. Anyone who has tasted Old Milwaukee can assure you it does get better than this. But any dubious, subjective claim might still sell something, so long as buyers can at least pretend to believe it. Capitalism needs to make—at the very least—a hypothetical promise of fulfillment and anything so hard to come by is an easy sale, especially when it’s cheap and one is poor.

Because civilization requires class divisions to create a labor pool to do menial and dangerous work, so long as it exists there will always be those whose only contentment will come from some product or other. Television, alcohol, drugs, refined sugar, and gambling might head a list of such surrogates. If we see civilization as a vicious pyramid scheme and not the advanced condition of society that it claims to be, the role of chemical and media distractions in our lives becomes clear. If life doesn’t get any better than Old Milwaukee beer, then that is what we’ll buy. If eating is the closest thing to love we feel, then eat we will. And someone always wins the lottery, after all.

For many, substances and entertainment become not an augmentation to a satisfying life, but a substitute, and the effects vary widely from person to person and group to group. Alcohol has a much more devastating effect on those with little metabolic ability to process it, for example, and it’s an insidious process. The onetime casual drinker might find herself absorbed by a daily ten drinks. The occasional betting man may come to see his savings, house, and family vanish into a casino. Diversion often becomes addiction; self-medication transforms into crisis.

Clinical psychologist Janina Fisher summarizes this progression: “The first assumption is that any addictive behavior begins as a survival strategy: as a way to numb, wall off intrusive memories, self-soothe, increase hypervigilance, combat depression, or facilitate dissociating. The addiction results from the fact that these psychoactive substances require continual increases in dosage to maintain the same self-medicating effect and eventually are needed just to ward off physical and emotional withdrawal.” [1]

In our last essay [2] we reviewed the options available to the one in four US adults who suffer from a “diagnosable mental disorder,”[3] options that increasingly are dominated by psychiatric medications. While these popular drugs may be useful as a short-term remedy to severe problems, behavior and talk therapy appears to be more durable and less risky. [4] Yet given a choice between months or years of hard, introspective work and a pill that takes a second to swallow, it isn’t surprising that many take the shortcut. One out of three doctor’s office visits by women, for instance, include prescription of an antidepressant drug. [5]

Antidepressants and antipsychotics sales multiplied almost fifty times from 1985 to 2008, to $24.2 billion. [6] Sales of prescription antidepressants declined from $11.6 billion in 2010 to $11 billion in 2011; [7] by comparison, liquor sales hit $19.9 billion in 2011, up 4 percent from 2010. [8] And this is only in the US, where seventy-nine thousand deaths are blamed on alcohol annually and alcoholism is the third highest lifestyle-related cause of death. About 40 percent of US hospital beds not devoted to maternity and intensive care are occupied by someone with an alcohol-related illness. [9] Americans spend a lot of money on booze and its aftereffects.

Because most alcoholics will insist there is no problem—or at least no alcohol problem—it’s impossible to say whether a bottle of vodka is for harmless leisure or desperate treatment of a harrowing emotional emergency. Alcoholism is hard to define, and no one even clearly understands how alcohol works on the human body. Any addiction is hard to define. It could simply be something you can’t stop. The American Heritage Dictionary calls it “the condition of being habitually or compulsively occupied with or involved in something,” a “compulsive physiological or psychological need for a habit-forming substance.”

Most humans have a desire to feel good, to minimize pain and effort and maximize ease and pleasure. We also seem to enjoy repeated experiences; watch someone at a slot machine sometime, mechanically feeding coin after coin, eerily rapt. Who doesn’t want a sense of meaning and substance to their days, a feeling of profundity, or simply relief from worry and regret? These can be achieved through discipline, surrender of controlling behaviors and cultivation of new behaviors—all without damaging your body and mind—but you can also find a toxic mimic of peace of mind by medicating yourself with chemicals or passive, fabricated experiences. The latter options have a grim list of negative consequences, from liver cirrhosis to obesity to insanity, all of which distance the user from authenticity, adventure, and self-respect. Pornography and alcohol aren’t known for aiding good romantic relationships, and an oxycontin monkey on your back will not steer you to happiness. Yet the prevalence of addictive behavior and the damage it causes shows that many try anyway.

The Problem with Alcohol

Our own experience with chemicals varies widely, as it does with anyone: To pick alcohol as maybe the most common of civilization’s intoxicants, Hyatt has been good and drunk—staggering, vomiting—only twice in her life. Carter, on the other hand, never met a drink he couldn’t live with, or a cigarette he didn’t like. In his prime he could put away a six-pack of strong beer and a bottle of wine a night with only a faint headache the next day. Certainly by some definitions this is alcoholism. Though he hasn’t smoked for seven years or drank any alcohol for a year and a half, they remain for him substances with a lingering, obsessive attraction, a rueful glamorous draw. He can’t watch someone have a smoke without a mix of disgust and ragged envy. It doesn’t last long and it’s only a tiny struggle to get past the feelings, but they are there.

The problem with alcohol, an experienced therapist tells us, is that we put it in our mouths. Just like the problem with oil and coal is that we burn it. Until we engage with it, it just sits there, benign and innocuous; when we do engage it, it becomes a relationship. We don’t ordinarily think of interactions with chemicals to be relationships, so it’s hard to imagine “abusing” them. Do drug abusers punch their needles, yell at their pills? When people intentionally cut themselves, they’re not abusing the knife.

It’s more a question of how we choose to treat ourselves. Consider a bad relationship you’ve been in. Remember the pattern of alternating moments of clinging and rejection, bliss and sour regret, warm contentment and self-loathing, sure belonging and desolate unworthiness. Once a relationship becomes abusive, it doesn’t stop being abusive, it only lingers and escalates, doing more damage. Power is being exerted in a bewilderingly damaging way.

Addiction may be the advanced condition of a toxic relationship, and the only way life improves then is to end the relationship. Any reforming alcoholic can tell you the attraction of living without alcohol isn’t in the absence of booze, the void where the relationship was; it’s in the promise of vitality, surprise, and freedom from intoxicated depression in new relationships.

The Anatomy of Avoidance

Our way of life, which we did not choose, requires most of us to spend most of our waking time at jobs that make us unhappy.[10] Our sense of optimism and interest in life erodes when what we want to do is usually subordinate to what we have to do. This is the baseline of civilized existence, the background circumstances. The amount of time spent at work is something humans haven’t evolved with—instead it is a condition that spread by conquest, like agriculture and industry. We are still creatures of the Paleolithic, leading lives based on entrapment by a contrived economy.

Add some everyday stressors: appointments, family conflicts, arguments with partners, fear of violence, illnesses, even small annoyances. If work weren’t a necessity—the bind nearly all civilized people are in—these stressors wouldn’t amount to much more than everyday matters easily resolved. If staying home and tending to a child’s illness didn’t get you fired, it wouldn’t be that big a deal. In healthy, intact indigenous cultures, light-heartedness is the normal condition. [11] In civilization, it’s a rarity, the most ephemeral enjoyment. It’s no wonder we avoid every hard task we can. Paradoxically, work itself is a highly acceptable method of avoidance, though a hard-driven capitalist can do more damage than a homeless crack addict could ever dream of.

This isn’t avoidance in the sense of swerving to avoid a car crash; instead, it’s a pattern of learned behavior, a way of responding to negative feelings. It’s our responses, rather than the negative feelings themselves, that determine our emotional condition. Emotional learning takes place whether perceived threats actually exist or not. [12] If you avoid bathing for fear of sharks in the tub, even if you know full well how irrational the fear is you still condition yourself to a response—you’re rewarded by the alleviation of your discomfort by not doing what it is you fear. But of course some problems remain, and grow.

Procrastination is a classic example of avoidance behavior that breeds anxiety because the thing we’re putting off continues to plague and unsettle. The perceived discomfort of resolution continues to escalate out of proportion to reality. How big a deal is it to wash the dishes? An extremely big deal, eventually. Pile on some more serious tasks like resolving an argument or a medical issue, and you have a mess easily soothed by booze, a pill, a casual hook-up (who hopefully doesn’t mind a reeking sinkful of dishes). These temporary fixes don’t resolve the problems, however. When they are habit forming and have their own destructive consequences, they become additional problems, also easy to mediate by simply continuing them. Problem drinkers know well that nothing fixes a hangover like the hair of the dog.

Avoidance becomes a part of your personality, and a way of life. It becomes more oppressive than all you’re avoiding; it demands your energy and attention, until you can feel it pressing in on you from outside, worrying itself from the inside. It nags and cajoles, urges quick solutions, makes self-serving promises. It is the parent of indifference, the older sibling to addiction. Apathy and numbing are defenses against the overwhelming anxiety formed by avoidance. For anyone working for social and environmental justice, where trauma and loss are everyday realities, avoidance can be very attractive, but eventually disastrous. How can anyone live fully in (let alone protect) the world if they are stuck in habits that lead to disconnection and withdrawal from the world?

Treatment Options

By the time an alcohol or drug problem becomes serious enough that it can’t be ignored, when a DUI or organ failure or intervention by others has forced it out of the protection racket of avoidance, the sufferer’s life is likely so compromised by damaged relationships and financial problems that finding the resources to deal with it can be extremely difficult. Until the advent of Alcoholics Anonymous in 1935, there was no very effective means of treating alcoholism. AA and its spinoffs—Narcotics Anonymous, Gamblers Anonymous, and others organized around the Twelve Steps principles of recovery—don’t offer a huge statistical hope of success, but they do offer some, [13] and are far better than the snake pit asylums that used to await chronic alcoholics.

Twelve Step groups and the spiritual, community-oriented recovery plan they use are controversial. The language of the Steps [14] sounds suspiciously Christian in tone, though in practice it’s entirely secular; no particular religious group sponsors AA. The organization holds that alcoholism is a disease, a view that’s strenuously objected to by other recovery approaches. [15] The multiple methods now available are good news for addicts, who’d be well advised to be open to anything that might work. Scrutinizing the life preserver when you’ve gone down for the proverbial third time is as good a description of the insanity of addiction as any.

This doesn’t mean that any one thing or another will work, of course. AA members, well aware of how their message is often doubted, like to say “take what you need and leave the rest.” One therapist we talked with, skeptical of AA, nevertheless remarked that disliking AA is one of the best reasons to go to their meetings, because it makes you think about—and hopefully begin to understand—the nature of your problems. In this small space, we can offer only a quick analysis of Twelve Step programs; we think they’re well worth looking into for their widespread presence, emphasis on engagement with others, and group problem-solving. And they’re free.

There are no other settings we’re aware of where one can be well-understood, respectfully listened to, and given zero slack for rationalizing bullshit. Alcoholics tend to believe they’re some sort of tragically, perhaps terminally unique actors on a sadist’s stage, shat upon daily by an unjust god. Hearing the same experiences of others on a routine basis (newcomers to AA are encouraged to attend ninety meetings in ninety days) dissolves this addiction-serving worldview, and builds a sense of community and common interest with others where once only egocentrism and false pride stood.

Any member of the dominant culture could well use just such a transformation. Only the incremental deposing of assumed godlike power will rescue the biosphere from civilization. The experiences of wretched addicts, who have managed to surrender control, are relevant to all who wish to understand how this mechanism might work. Addiction is one of civilization’s options for hiding from responsibility, for staying in denial, for avoiding our duty to the living world. Recovery means finding a healthy way of listening to our anxieties and engaging with others to create and live a meaningful life.

Bibliography and Further Reading

- Alcoholics Anonymous World Services. Alcoholics Anonymous. New York: AA World Services, 2001.

- ________. Twelve Steps and Twelve Traditions. New York: AA World Services, 1994.

- Evans, Patricia. The Verbally Abusive Relationship: How to Recognize It and How to Respond. Avon, MA: Adams Media, 2010.

- Friends in Recovery. Edited by Kathleen W. 12 Steps to Freedom: A Recovery Workbook. Freedom, CA: The Crossing Press, 1991.

- Fuller, Alexander. “In the Shadow of Wounded Knee,” National Geographic, August 2012, 51.

- Glendinning, Chellis. My Name is Chellis and I’m in Recovery from Western Civilization. Boston: Shambhala Publications, 1994.

- Leventhal, Allan M. and Martell, Christopher R. The Myth of Depression as Disease: Limitations and Alternatives to Drug Treatment. Westport, CT: Praeger Publishers, 2006.

- Peele, Stanton. Diseasing of America: Addiction Treatment out of Control.Lexington, MA: Lexington Books, 1989

- Trimpey, Jack. Rational Recovery. New York: Pocket Books, 1996.

- Villar, Oliver and Cottle, Drew. Cocaine, Death Squads, and the War on Terror: U.S. Imperialism and Class Struggle in Colombia. New York: Monthly Review Press, 2011.

Online

- Rohith Sebastian, “A New Approach to Overcoming Psychological Disorders,” Psych Central, accessed May 7, 2014,http://psychcentral.com/blog/archives/2014/04/10/a-new-approach-to-overcoming-psychological-disorders/

- Kyung Jin Lee, “Capitalism Makes Us Crazy: Dr. Gabor Maté on Illness and Addiction,” TruthOut, June 1, 2013, http://www.truth-out.org/news/item/16711-capitalism-makes-us-crazy-dr-gabor-mate-on-illness-and-addiction

- Jamie Doward, “Medicine’s big new battleground: does mental illness really exist?” The Observer, May 11, 2013,http://www.theguardian.com/society/2013/may/12/medicine-dsm5-row-does-mental-illness-exist

- Corrinne Burns, “Are mental illnesses such as PMS and depression culturally determined?” The Guardian, May 20, 2013,http://www.theguardian.com/science/blog/2013/may/20/mental-illnesses-depression-pms-culturally-determined

- Medical University of Vienna, “Depression detectable in the blood: Platelet serotonin transporter function,” ScienceDaily, April 29, 2014,www.sciencedaily.com/releases/2014/04/140429105015.htm

- Matthew Miller, MD, ScD1; Sonja A. Swanson, ScM2; Deborah Azrael, PhD1; Virginia Pate, PhD, PhD3; Til Stürmer, MD, ScD3, “Antidepressant Dose, Age, and the Risk of Deliberate Self-harm,” JAMA Intern Med., April 28, 2014,http://archinte.jamanetwork.com/article.aspx?articleid=1863925

Endnotes

[1] Janina Fisher, Ph.D., “Addictions and Trauma Recovery,” Paper presented at the International Society for the Study of Dissociation, November 13, 2000,http://www.janinafisher.com/pdfs/addictions.pdf

[2] Susan Hyatt and Michael Carter, “Restoring Sanity, Part 2: Mental Illness as a Social Construct,” Deep Green Resistance Southwest Coalition, March 13, 2014, http://deepgreenresistancesouthwest.org/2014/03/13/restoring-sanity-part-2-mental-illness-as-a-social-construct/

[3] Kessler RC, Chiu WT, Demler O, Walters EE, “Prevalence, severity, and comorbidity of twelve-month DSM-IV disorders in the National Comorbidity Survey Replication (NCS-R),” Archives of General Psychiatry, 2005 Jun;62(6):617-27.

[4] “Studies have shown that behavior therapy provides remedies that are longer-lasting and pose no concerns regarding side effects.” Leventhal and Martell, p. 137.

“A growing number of overdoses of legal opioids, sedatives and tranquilizers led to a 65 percent increase in hospitalizations over seven years,” Katherine Harmon, “Prescription Drug Deaths Increase Dramatically,” Scientific American, April 6, 2010,http://www.scientificamerican.com/article/prescription-drug-deaths/ While not about psychiatric drugs in particular, this article does underscore the hazard in so many medications simply being at large, available for addictive use or accidental overdose and death.

[5] Leventhal and Martell, p. 135.

“Researchers say women are more likely to have depression and anxiety, while more men report substance abuse,” James Ball, “Women 40% more likely than men to develop mental illness, study finds,” The Guardian, 22 May 2013,http://www.theguardian.com/society/2013/may/22/women-men-mental-illness-study

[6] John Horgan, “Are Psychiatric Medications Making Us Sicker?” Scientific American, March 5, 2012, http://blogs.scientificamerican.com/cross-check/2012/03/05/are-psychiatric-medications-making-us-sicker/

“Writing a prescription to treat a mental health disorder is easy, but it may not always be the safest or most effective route for patients, according to some recent studies and a growing chorus of voices concerned about the rapid rise in the prescription of psychotropic drugs,” Brendan L. Smith, “Inappropriate prescribing,” June 2012 Monitor on Psychology, June 2012, Vol 43, No. 6, print version: page 36, https://www.apa.org/monitor/2012/06/prescribing.aspx

[7] Craig W. Lindsley, “The Top Prescription Drugs of 2011 in the United States: Antipsychotics and Antidepressants Once Again Lead CNS Therapeutics,” ACS Chem. Neurosci., 2012, 3 (8), pp 630–631, August 15, 2012,http://pubs.acs.org/doi/full/10.1021/cn3000923 The ACS is the American Chemical Society. The figures for drug sales are located on Table 2.

[8] Brad Tuttle, “Cheers! Increase in Liquor Sales Bodes Well for Economic Recovery,” Time, January 31, 2012,http://business.time.com/2012/01/31/cheers-increase-in-liquor-sales-bodes-well-for-economic-recovery/

[9]“Facts about Alcohol,” National Council on Alcoholism and Drug Dependence, accessed February 10, 2011.

[10] “According to the Gallup 2013 State of the American Workplace report, 52 percent of American full-time workers said they were ‘disengaged’ at work, meaning that they put time and effort into their work, but didn’t have energy or passion for it. Together, 70 percent of employees said they were either ‘disengaged’ or ‘actively disengaged,’ the latter term defining workers who openly express their discontent and undermine the efforts of their engaged colleagues. Just 30 percent of the workers polled said they felt ‘engaged’ at work, meaning they are ‘involved in, enthusiastic about, and committed to their work and contribute to their organization in a positive manner.’” Eli Epstein, “How many Americans are unhappy at work?” MSN News, June 25, 2013,http://news.msn.com/us/how-many-americans-are-unhappy-at-work

[11] “In one study, researchers used a storytelling technique to evaluate three groups of Kenyan women: rural women in a traditional village, poor urban women, and middle-class urban women…traditional women almost always told very positive stories that usually had a happy ending. Middle-class urban women told stories that emphasized their own power and competence. Poor urban women’s stories were generally tragic and focused on powerlessness and vulnerability. The researchers note that many poor urban women have ‘lost the security and protection of the old [traditional] system without gaining the power or rewards of the new system,’” Friedman, Ariellad and Todd, Judith. “Kenyan Women Tell a Story: Interpersonal Power of Women in Three Subcultures in Kenya.” Sex Roles 31: 533-546, in Nanda, Serena and Warms, Richard L.Cultural Anthropology. Belmont, CA: Wadsworth/Thomson, 2004, 387, 388.

[12] Leventhal and Martell, p. 82.

[13] “Accurate reports about the success rates of 12-step programs like AA and NA are notoriously difficult to obtain. The few studies that have attempted to measure the effectiveness of the program have often been contradictory. Fiercely protective of their anonymity, AA forbids researchers from conducting clinical studies of its millions of members. But the organization does conduct its own random surveys every three years. The result of AA’s most recent study in 2007 were promising. According to AA, 33 percent of the 8,000 North American members it surveyed had remained sober for over 10 years. Twelve percent were sober for 5 to 10 years; 24 percent were sober 1 to 5 years; and 31 percent were sober for less than a year,” Kevin Gray, “Does AA Really Work? A Round-Up of Recent Studies,” The Fix, January 29, 2012,http://www.thefix.com/content/the-real-statistics-of-aa7301

[14] “The Twelve Steps of Alcoholics Anonymous: 1. We admitted we were powerless over alcohol—that our lives had become unmanageable. 2. Came to believe that a Power greater than ourselves could restore us to sanity. 3. Made a decision to turn our will and our lives over to the care of God as we understood Him. 4. Made a searching and fearless moral inventory of ourselves. 5. Admitted to God, to ourselves, and to another human being the exact nature of our wrongs. 6. Were entirely ready to have God remove all these defects of character. 7. Humbly asked Him to remove our shortcomings. 8. Made a list of all persons we had harmed, and became willing to make amends to them all. 9. Made direct amends to such people wherever possible, except when to do so would injure them or others. 10. Continued to take personal inventory and when we were wrong promptly admitted it. 11. Sought through prayer and meditation to improve our conscious contact with God, as we understood Him, praying only for knowledge of His will for us and the power to carry that out. 12. Having had a spiritual awakening as the result of these Steps, we tried to carry this message to alcoholics, and to practice these principles in all our affairs.” A.A. World Services, Inc., May 9, 2002, www.aa.org/en_pdfs/smf-121_en.pdf

[15] “Peer-reviewed studies peg the success rate of AA somewhere between 5 and 10 percent. That is, about one of every fifteen people who enter these programs is able to become and stay sober. In 2006, one of the most prestigious scientific research organizations in the world, the Cochrane Collaboration, conducted a review of the many studies conducted between 1966 and 2005 and reached a stunning conclusion: ‘No experimental studies unequivocally demonstrated the effectiveness of AA’ in treating alcoholism. This group reached the same conclusion about professional AA-oriented treatment (12-step facilitation therapy, or TSF), which is the core of virtually every alcoholism-rehabilitation program in the country,” Lance Dodes and Zachary Dodes, “Sober Truth: Debunking the Bad Science Behind 12-Step Programs and the Rehab Industry,” excerpt in “AA and Rehab Culture Have Shockingly Low Success Rates,” AlterNet, April 2, 2014, http://www.alternet.org/books/pseudoscience-aa-and-rehab?paging=off¤t_page=1#bookmark

Peele, 1989.

Trimpey, 1996.

Susan Hyatt has worked as a project manager at a hazardous waste incinerator, owned a landscaping company focused on native Sonoran Desert plants, and is now a volunteer activist. Michael Carter is a freelance carpenter, writer, and activist. His anti-civilization memoir Kingfisher’s Song was published in 2012. They both volunteer for Deep Green Resistance Southwest Coalition.

From DGR Southwest Coalition: “Restoring Sanity Part 3: Medicating”