by DGR News Service | Nov 24, 2021 | Biodiversity & Habitat Destruction, Human Supremacy, Mining & Drilling, The Problem: Civilization

This story first appeared in Mongabay.

Editor’s note: O Canada! Welcome to the new wild west. If you liked Deepwater Horizon you will love Deep Sea Mining. This statement pretty much sums it up, “countries could have their chance to EXPLOIT the valuable metals locked in the deep sea.” Corporations love to deal with poorer, less developed countries who can do less by way of supervision because they lack greater resources and capacity.

“Like NORI, TOML began its life as a subsidiary of Nautilus minerals, one of the world’s first deep-sea miners. Just before Nautilus’s project in Papua New Guinea’s waters failed and left the country $157 million in debt, its shareholders created DeepGreen. DeepGreen acquired TOML in early 2020 after Nautilus filed for bankruptcy, the ISA said the Tongan government allowed the transfer and reevaluating the company’s background was not required.”

And mining royalties are paid to the ISA. If this doesn’t sound fishy, I don’t know what does. There never should be a question as to what a corporation’s angle is. Their loyalty always is to the stockholders.

By Ian Morse

- Citizens of countries that sponsor deep-sea mining firms have written to several governments and the International Seabed Authority expressing concern that their nations will struggle to control the companies and may be liable for damages to the ocean as a result.

- Liability is a central issue in the embryonic and risky deep-sea mining industry, because the company that will likely be the first to mine the ocean floor — DeepGreen/The Metals Company — depends on sponsorships from small Pacific island states whose collective GDP is a third its valuation.

- Mining will likely cause widespread damage, scientists say, but the legal definition of environmental damage when it comes to deep-sea mining has yet to be determined.

Pelenatita Kara travels regularly to the outer islands of Tonga, her low-lying Pacific Island home, to educate fishers and farmers about seabed mining. For many of the people she meets, seabed mining is an unfamiliar term. Before Kara began appearing on radio programs, few people knew their government had sponsored a company to mine minerals from the seabed.

“It’s like talking to a Tongan about how cold snow is,” she says. “Inconceivable.”

The Civil Society Forum of Tonga, where Kara works, and several other Pacific-based organizations have written to several governments and the International Seabed Authority (ISA) to express concerns that their countries may end up being responsible for environmental damage that occurs in the mineral-rich Clarion-Clipperton Zone, an expanse of ocean between Hawai‘i and Mexico.

“The Pacific is currently the world’s laboratory for the experiment of Deep Seabed Mining,” the groups wrote to the ISA, the U.N.-affiliated body tasked with regulating the nascent industry. As a state that sponsors a seabed mining company, Tonga has agreed to shoulder a significant amount of responsibility in this fledgling industry that may threaten ecosystems that are barely understood. And if anything goes wrong in the laboratory, Kara is worried that Tonga’s liabilities could exceed its ability to pay. If no one can pay for remediation, Greenpeace notes, that may be even worse.

“My concern is that the liability from any problem with deep-sea mining will just be too much for us,” Kara says.

Another Pacific Island state, Nauru, notified the ISA in June that a contractor it sponsors is applying for the world’s first deep-sea mining exploitation permits. The announcement triggered the “two-year rule,” which compels the ISA to consider the application within that period, regardless of whether the exploitation rules and regulations are completed by then.

Among the rules that may not be decided upon by the deadline is liability: Who is responsible if something goes wrong? Sponsoring states like Nauru, Tonga and Kiribati — which all sponsor contractors owned by Canada-based DeepGreen, now The Metals Company — are required to “ensure compliance” with ISA rules and regulations. If a contractor breaches ISA rules, such as causing greater damage to ocean ecosystems than expected, the contractor may be held liable if the sponsoring state did all they could to enforce strict national laws.

However, it’s not yet clear how these countries can persuade the ISA that they enforced the rules, nor how they can prove that they are able to control the contractors, when the company is foreign-owned. The responsibility of sponsoring states to fund potentially billions of dollars in environmental cleanup depends on the legal definitions of terms like “environmental damage” and “effective control,” which may be as murky two years from now as they are at present.

Myriad problems may occur in the mining area: sediment plumes may travel thousands of kilometers and obstruct fisheries, or damage could spread into other companies’ areas. Scientists don’t know all the possible consequences, in part because these ecosystems are poorly understood. The ISA has proposed the creation of a fund to help cover the costs, but it’s not clear who will pay into it.

“The scales of the areas impacted are so great that restoration is just not feasible,” says Craig Smith, an oceanography professor emeritus at the University of Hawai‘i, who has worked with the ISA since its creation in 1994. “To restore tens or hundreds of thousands of square kilometers would be probably more expensive than the mining operation itself.”

Nauru voices concerns

Just over a decade ago, before Nauru agreed to sponsor a deep-sea mining permit, the government worried that it was going to find itself responsible for paying those damages. The government wrote to the International Tribunal for the Law of the Sea, voicing concerns about the liability it could incur. As a sponsoring state with no experience in deep-sea mining and a small budget to support it, the delegation wanted to make sure that the U.N. did not prioritize rich countries in charting this new frontier in mineral extraction. Nauru and other “developing” countries should have just as great an opportunity to benefit from mining as other countries with more experience in capital-intensive projects, they argued.

Sponsoring states like Nauru are required to ensure their contractors comply with the law but, the delegation wrote, “in reality no amount of measures taken by a sponsoring State could ever fully ‘secure compliance’ of a contractor when the contractor is a separate entity from the State.”

Seabed mining comes with risks — environmental, financial, business, political — which sponsoring states are required to monitor. According to Nauru’s 2010 request, “it is unfortunately not possible for developing States to perform their responsibilities to the same standard or on the same scale as developed States.” If the standards of those responsibilities varied according to the capabilities of states, the Nauru delegation wrote, both poor and rich countries could have their chance to exploit the valuable metals locked in the deep sea.

“Poorer, less developed states, it was argued, would have to do less by way of supervision because they lacked greater resources and capacity,” says Don Anton, who was legal counsel to the tribunal during the decision on behalf of the IUCN, the global conservation authority.

The tribunal, issuing a final court opinion the next year, disagreed. Each state that sponsored a deep-sea miner would be required to uphold the same standards of due diligence and measures that “ensure compliance.” Legal experts generally regarded the decision well, because it prevented contractors from seeking sponsorships with states that placed lower requirements on their activities. However, according to Anton, the decision meant that countries with limited budgets like Nauru have only two choices when they consider deep-sea mining: either sponsor a contractor entirely, or avoid the business altogether.

According to the tribunal’s decision, “you cannot excuse yourself as a sponsoring state by referring to your limited financial or administrative capacity,” says Isabel Feichtner, a law professor at the University of Würzburg in Germany. “And that of course raises the question: To what extent can a small developing state really control a contractor who might just have an office in that state?”

Nauru had just begun sponsoring a private company to explore the mineral riches at the bottom of the sea Clarion-Clipperton Zone. Nauru Ocean Resources Inc. (NORI), initially a subsidiary of Canada-based Nautilus Minerals, transferred its ownership to two Nauru foundations while the founder of Nautilus remained on NORI’s board. As a developing state, Nauru said, this kind of public-private partnership was the only way that it could join mineral exploration.

Nauru discussed the tribunal’s decision behind closed doors, according to a top official there at the time, and the government sought no independent consultation, hearing only guidance from Nautilus. Two months after the tribunal gave its opinion, Nauru officially agreed to sponsor NORI.

Control

After the tribunal’s decision, the European Union recognized that writing the world’s first deep-sea mining rules to govern companies thousands of miles away would be a tall order for countries with little capacity to conduct research.

The EU, whose member states also sponsor mining exploration, began in 2011 a 4.4 million euro ($5.1 million) project to help Pacific island states develop mining codes. However, by 2018, when most states had finished drafting national regulations, the Pacific Network on Globalization (PANG) found that the mining codes did “not sufficiently safeguard the rights of indigenous peoples or protect the environment in line with international law.” In addition, in some cases countries enacted legislation before civil society actors were aware that there was legislation, says PANG executive director Maureen Penjueli.

“In our region, most of our legislation assumes impact is very small, so there’s no reason to consult widely,” she says. “We found in most legislations is that it is assumed it’s only where mining takes place, not where impacts are felt.”

For Kara, mining laws are one thing, but enforcement is another. Sponsoring states must have “effective control” over the companies they sponsor, according to mineral exploration rules, but the ISA has not explicitly defined what that means. For example, the exploration contract for Tonga Offshore Mining Limited (TOML) says that if “control” changes, it must find a new sponsoring state. When DeepGreen acquired TOML in early 2020 after Nautilus filed for bankruptcy, the ISA said the Tongan government allowed the transfer and reevaluating the company’s background was not required.

Kara questions whether Tonga can adequately control TOML, its management, and its activities. TOML is registered in Tonga, but its management consists of Australian and Canadian employees of DeepGreen. It is owned by the Canadian company. Since DeepGreen acquired TOML, the only Tongan national in the company is no longer listed in a management role.

“It’s not enough to be incorporated in the sponsoring state. The sponsoring state must also be able to control the contractor and that raises the question as to the capacity to control,” Feichtner says.

When Kara’s Civil Society Forum of Tonga and others wrote to the ISA, they argued Canada should be the state sponsor of TOML, considering TOML is owned by a Canadian firm. In response, the ISA wrote that the Tongan government “has no objection” to the management changes, so no change was needed.

“Of all the work they’re doing in the area, I don’t know whether there’s any Tongan sitting there, doing the so-called validation and ascertaining what they do. We’re taking all of this at face value,” Kara says. With few resources to track down people who live in Canada or Australia, Kara is worried that Tonga will not be able to hold foreign individuals accountable for problems that may arise.

In merging with a U.S.-based company, DeepGreen became The Metals Company and will be responsible to shareholders in the U.S. The U.S., however, has not signed on to the U.N. convention that guides the ISA, and as such is not bound by ISA regulations, the only authority governing mining in the high seas.

“What I think is pretty clear is that ‘effective control’ means economic, not regulatory, control,” says Duncan Currie, a lawyer who advises conservation groups on ocean law. “So wherever it is, it’s not in Tonga.”

The risks

On Sept. 7, Tonga’s delegation to the IUCN’s global conservation summit in France joined 80% of government agencies that voted for a motion calling for a moratorium on deep-sea mining until more was known about the impacts and implications of policies.

“As a scientist, I am heartened by their decision,” says Douglas McCauley a professor of ocean science at the University of California, Santa Barbara. “The passage of this motion acknowledges research from scientists around the world showing that ocean mining is simply too risky a proposition for the planet and people.”

Tonga’s government continues to sponsor an exploration permit for TOML. According to the latest information, Tonga and TOML have agreed that the company will pay $1.25 in royalties for every ton of nodules mined. That may amount to just 0.16% of the value of the activities the country sponsors, according to scenarios presented to the ISA by a group from the Massachusetts Institute of Technology. Royalties paid to the ISA and then distributed to countries may be around $100,000.

Nauru’s contract with NORI stipulates that the company is not required to pay income tax. DeepGreen has reported in filings to the U.S. Securities and Exchange Commission that royalties will not be finalized until the ISA completes the exploitation code. With the two-year rule, NORI plans to apply for a mining permit, regardless of when the code is written.

“The only substantial economic benefit [Nauru] might derive is from royalty payments, and these are not even specified yet. and on the other hand, it potentially incurs this huge liability if something goes wrong,” Feichtner says.

Like NORI, TOML began its life as a subsidiary of Nautilus minerals, one of the world’s first deep-sea miners. Just before Nautilus’s project in Papua New Guinea’s waters failed and left the country $157 million in debt, its shareholders created DeepGreen.

“I am afraid that Tonga will be another Papua New Guinea,” Kara says. “If they start mining and something happens out there, we don’t have the resources, the expertise, because we need to validate what they’re doing.”

DeepGreen has said it is giving “developing” states like Tonga the opportunity to benefit from seabed mining without shouldering the commercial and technical risk. DeepGreen did not respond to Mongabay’s requests for comment.

“I’m still trying to figure out their angle. Personally, I think DeepGreen is using Pacific islanders to hype their image. I’m still thinking that we were never really the target. The shareholders have always been their target,” Kara says.

She says she doubts the minerals at the bottom of the ocean are needed for the world to transition away from fossil fuels. In a letter to a Tongan newspaper, Kara wrote, “Deep-sea mining is a relic, left over from the extractive economic approaches of the ’60s and ’70s. It has no place in this modern age of a sustainable blue economy. As Pacific Islanders already know — and science is just starting to learn — the deep ocean is connected to shallower waters and the coral reefs and lagoons. What happens in the deep doesn’t stay in the deep.”

by DGR News Service | Oct 13, 2021 | Biodiversity & Habitat Destruction, Mining & Drilling, Toxification

This article originally appeared in Mongabay.

Editor’s note: We know less about the bottom of the sea than we know about outer space. We really require no scientific evidence to know that mining is bad for the environment wherever it occures. It should not be done on land, under the sea or on other planets. The ISA needs to reject the deep sea mining industry’s claims that mining for metals on the ocean floor is a partial solution to the climate crisis. As Upton Sinclair said, “it’s difficult to get a man to understand something when his salary depends on his not understanding it.” We can see this with the archeologist working for Lithium America in Thacker Pass. An interesting film to watch on the twisted relationship between science and industry is The Last Winter.

by Elham Shabahat

- The high cost of studying deep-sea ecosystems means that many scientists have to rely on funding and access provided by companies seeking to exploit resources on the ocean floor.

- More than half of the scientists in the small, highly specialized deep-sea biology community have worked with governments and mining companies to do baseline research, according to one biologist.

- But as with the case of industries like tobacco and pharmaceuticals underwriting scientific research into their own products, the funding of deep-sea research by mining companies poses an ethical hazard.

- Critics say the nascent industry is already far from transparent, with much of the data from baseline research available only to the scientists involved, the companies, and U.N.-affiliated body that approves deep-sea mining applications.

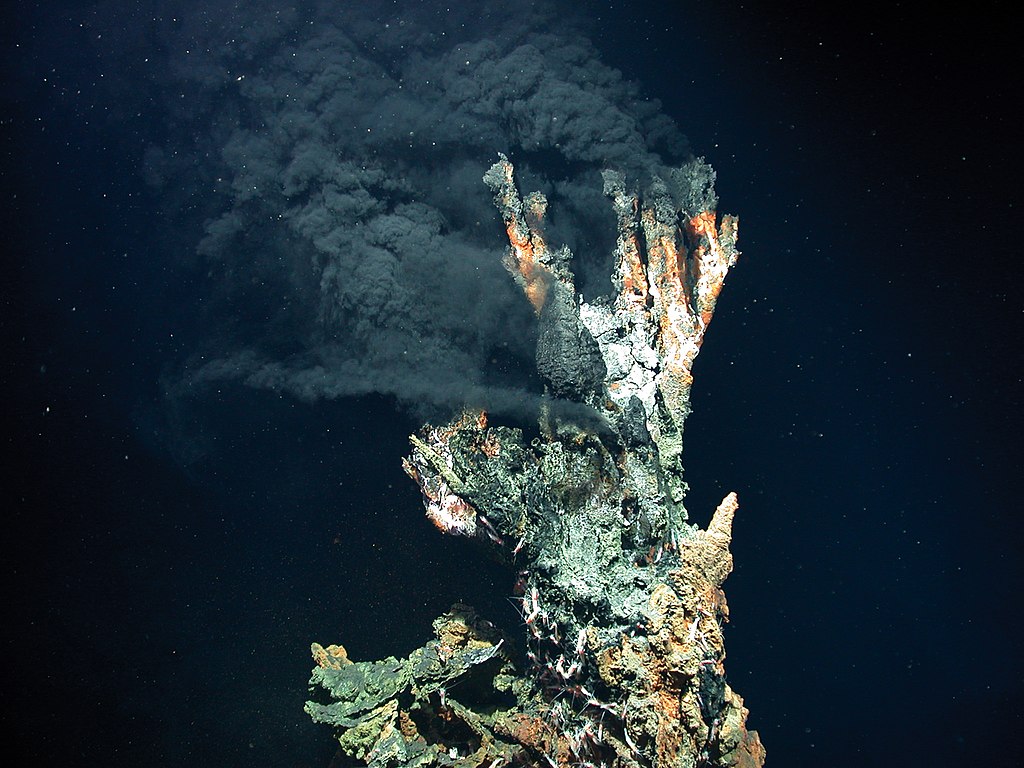

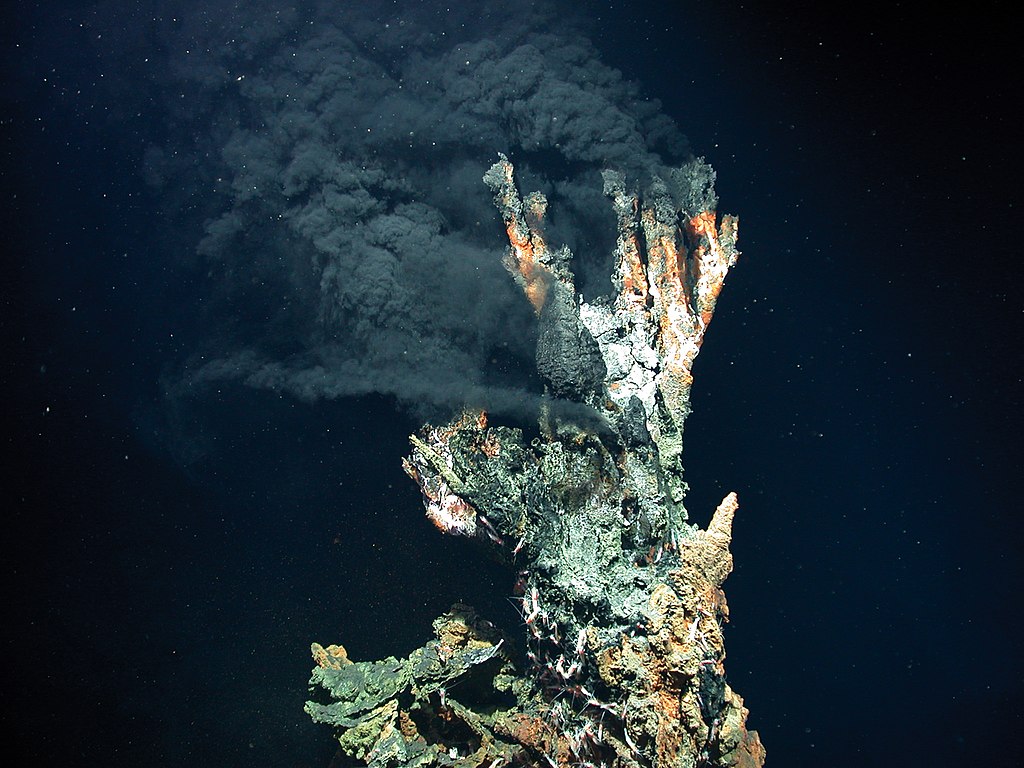

When Cindy Van Dover started working with Nautilus Minerals, a deep-sea mining company, she received hate mail from other marine scientists. Van Dover is a prolific deep-sea biologist, an oceanographer who has logged hundreds of dives to the seafloor. In 2004, Nautilus invited Van Dover and her students to characterize ecosystems in the Manus Basin off Papua New Guinea, a potential mining site with ephemeral hydrothermal vents teeming with life in the deep ocean.

Van Dover was the first academic deep-sea biologist to conduct baseline studies funded by a mining company, an act considered a “Faustian pact” by some at the time. Since then, more deep-sea biologists and early-career scientists aboard research vessels funded by these firms have conducted such studies. But partnering with mining companies raises some thorny ethical issues for the scientists involved. Is working with the mining industry advancing knowledge of the deep sea, or is it enabling this nascent industry? While there are efforts to disclose this scientific data, are they enough to ensure the protection of deep-sea ecosystems?

“I don’t think it’s sensible or right to not try to contribute scientific knowledge that might inform policy,” Van Dover said. With deep-sea mining, she added, “we can’t just stick our heads in the sand and complain when it goes wrong.”

More than half of the scientists in the small, highly specialized deep-sea biology community have worked with governments and mining companies to do baseline research, according to Lisa Levin, professor of biological oceanography at the Scripps Institution of Oceanography. Collecting biological samples in the deep sea is expensive: a 30-day cruise can cost more than $1 million. The U.S. National Science Foundation, the European Union and the National Science Foundation of China have emerged as top public funders of deep-sea research, but billionaires, foundations and biotech companies are getting in on the act, too.

Governments and mining companies already hold exploration licenses from the U.N.-affiliated International Seabed Authority (ISA) for vast swaths of the seafloor. Although still in an early stage, the deep-sea mining industry is on the verge of large-scale extraction. Mining companies are scouring the seabed for polymetallic nodules: potato-shaped rocks that take a millennium to form and contain cobalt, nickel and copper as well as manganese. Nauru, a small island in the South Pacific, earlier this year gave the ISA a two-year deadline to finalize regulations — a major step toward the onset of commercial deep-sea mining. The ISA is charged with both encouraging the development of the deep-sea mining industry and ensuring the protection of the marine environment, a conflict of interest in the eyes of its critics.

The Metals Company, a mining company based in Vancouver, Canada, formerly known as DeepGreen, recently said that it spent $75 million on ocean science research in the Clarion Clipperton Zone (CCZ) in the Pacific. The company has established partnerships with “independent scientific institutions” for its environmental and social impact assessments. Kris Van Nijen, managing director of Global Sea Mineral Resources said, “It is time, unambiguously and unanimously, to back research missions … Support the science. Let the research continue.” UK Seabed Resources, another deep-sea mining firm, lists significant scientific research that uses data from its research cruises in the CCZ.

The ISA requires mining companies to conduct baseline research as part of their exploration contracts. Such research looks to answer basic questions about deep-sea ecosystems, such as: what is the diversity of life in the deep sea? How will mining affect animals and their habitats? This scientific data, often the first time these deep-sea ecosystems have been characterized, is essential to assessing the impacts of mining and developing strategies to manage these impacts. Companies partner with scientific institutions across the United States, Europe and Canada to conduct these studies. But independence when it comes to alliances with industry is fraught with ethical challenges.

“If deep-sea science has been funded by interest groups such as mining companies, are we then really in a position to make the decision that is genuinely in the best interest of deep ocean ecosystems?” asks Aline Jaeckel, senior lecturer of law at the University of New South Wales in Australia. “Or are we heading towards mining, just by the very fact that mining companies have invested so heavily?”

The ethics of independent science

There’s a risk of potential conflicts of interest when scientists are funded by industry. While mining companies often tout working with independent scientists, in company-sponsored research vessels, “having somebody independent on board would be somebody who has presumably no financial affiliation in any way shape or form,” says Levin of the Scripps Institution of Oceanography.

When working with mining companies to collect baseline data, scientists are compensated through funding, which can be as high as $2.9 million, for their research labs. Many go on to publish journal articles based on data gathered on company-sponsored ships, advancing science in a relatively unknown realm where access is expensive and sparse.

While knowledge of the deep sea has advanced in recent decades, scientists are still trying to learn how these ecosystems are connected and the impact of mining over longer periods of time. The deep pelagic ocean — mid-water habitats away from the coasts and the seabed — is the least studied and chronically undersampled. There is also a dearth of deep-sea data for the Pacific, South Atlantic and Indian Oceans, where researchers (and mining companies) are increasingly focusing their attention.

For mining companies, science adds legitimacy, argues Diva Amon, a deep-sea biologist and director of SpeSeas, Trinidad and Tobago. “I think they recognize the value of science in appealing to consumers … and stakeholders as well.”

While it is common for scientific research to be funded by public agencies, when such funding dries up, scientists may be compelled to seek funding from or collaborate with interest groups. In other scientific endeavors like tobacco research, public health, climate science and clinical drug trials, there are policies to manage conflicts of interest, because history is rife with examples of industry influencing the design, outcome and communication of research in their favor. Some argue that even if industry-funded scientists publish research that is methodologically sound, industry influence on a broad scale can bias research results in imperceptible ways that erode trust in science.

Being funded by industry is not an issue if scientists are able to publish their research without restrictions, even if results are negative for the contractor, says Matthias Haeckel, a deep-sea biologist who is coordinating a mining impact project in the CCZ, funded by the European Union. “The question is if it’s up to this degree of independency, and that’s difficult to know from the outside … for me it’s sometimes a transparency issue. It’s not clear what the contracts with the scientists are.”

Deep-sea biologists have published research that does not work in the industry’s favor. A survey of megafauna diversity on the seafloor of the CCZ found that of the 170 identified animals, nearly half were found only on polymetallic nodules that are of interest to mining contractors. The study suggests that the nodules are an important habitat for species diversity. Biodiversity loss associated with mining is likely to last forever on human time scales, due to the slow rate of recovery in deep-sea ecosystems.

For some scientists, the key difference between being funded by an entity like the National Science Foundation versus the industry is control. Mining companies can ask scientists to sign nondisclosure agreements because companies in competition are concerned about the details of their sampling programs being made public, says Jeff Drazen, a deep-sea scientist at the University of Hawai‘i who is conducting research funded by The Metals Company. While there is a general understanding that scientists are free to publish their research, there can be embargos on when the research is released and requirements for consultation with the contractors.

“Many of them want you to sign an NDA before you can even talk to them. With the current contract we have with The Metals Company, none of our people have signed NDAs, and that was one of the reasons we decided to work with them,” Drazen says. “This is a common part of the business world to sign these NDAs — and that is antithetical to science, so that’s a cultural shift for most of us academics.”

The ISA has issued guidelines for baseline studies, but the decision of what and how much to sample rests on the company and scientists involved. “Scientists have to be careful not to necessarily be driven entirely by what the person funding the research wants,” says Malcolm Clark, a deep-sea biologist at New Zealand’s National Institute of Water and Atmospheric Research. “We’ve got to be very objective and make it very clear what’s required for a robust scientific project, and not just respond to the perceived needs of the client. Easy to say — very, very difficult to actually put into practice.” Clark also sits on the Legal and Technical Commission, a body within the ISA tasked with assessing mining applications.

‘Damned if you do, damned if you don’t’

Scientists are still trying to fathom the depths of our oceans, both to understand the sensitive ecosystems that thrive there, and the minerals that can be extracted from polymetallic nodules that have formed over millennia. Less than 1% of the deep sea has been explored. The interest in exploiting ocean minerals is coupled with advancements in scientific research. A study published earlier this year found that deep-sea research languished when this interest in exploitation waned in the 1980s and ’90s.

For baseline research, “if this fundamental first-time characterization of these ecosystems is going to be done, it should be done by experts, so there’s quality assurance,” Levin said in a lecture in 2018 on the ethical challenges of seabed mining. “You’re damned if you do and damned if you don’t at some level.”

There’s also the perceived conflict of interest: the intangible effects of working closely with industry representatives, where collecting data means going out together on a research vessel for several weeks at a time.

“We’re humans, we’re building relationships, and going to sea is a particularly bonding experience because you’re out there isolated and working together. I cannot imagine how that kind of relationship will not at some point interfere with scientific judgment,” says Anna Metaxas, a deep-sea biologist at the Dalhousie University in Canada, whose research has not been funded by mining companies. It’s not the collection of data that Metaxas is concerned about, “it’s what you do with the data and how you end up communicating to whom and when.”

“What I’m noticing with many PIs [primary investigators] working with mining contractors is that they don’t want to bite the hand that feeds them,” says Amon. “As a result, they are less willing to speak to the public and the press, which is really unfortunate.”

The Wall Street Journal reported that according to two people familiar with the matter, Jeff Drazen was facing the possibility of having his funding revoked after publicly criticizing seabed mining. In an interview with Mongabay, Drazen declined to comment on the matter.

Other prominent scientists who work with mining contractors did not respond to interview requests for this article.

The trouble with DeepData

Since the ISA started giving out exploration contracts, the data that contractors collected was kept in a “black box” for more than 18 years, hidden from the world with the key in the hands of the contractors, the scientists who conducted this research, and a few people within the ISA. Because academics are involved, some of this data and analysis would eventually become available as peer-reviewed scientific literature.

In 2019, the ISA developed DeepData, a public database where contractors are required to submit the baseline data they collect. But the only data available to the public is environmental data. Resource data, particularly related to polymetallic nodules that are of interest to mining contractors, is off-limits and remains proprietary. The distinction between environmental and resource data is a “gray area,” according to Clark. What is deemed confidential is up to the mining contractors and the secretary-general of the ISA.

The nodules, rich in metals such as cobalt and nickel, are a breeding ground for deep-sea octopuses, and home to new species of deep-sea sponges, diverse animals and microbes not found in surrounding waters or sediments. The communities of organisms that rely on these nodules and sediment vary with the abundance of the nodules.

“Miners are going after the components of the habitat,” says Craig Smith, a deep-sea scientist at the University of Hawai‘i. “But we can’t really assess the abundance of that habitat without knowing the abundance of the nodules.” In fisheries, for example, industry-sensitive data is aggregated to help with management decisions, but such data is considered proprietary for the nodules.

The metallic content of these nodules is also a trade secret, though the information could be relevant for environmental assessments. Toxicity from broken-down ores could be created in the sediment plumes or wastewater that’s reinjected in the water column as a byproduct of the mining process, potentially affecting fish and other biodiversity. Where exactly in the water column mining companies will discharge the wastewater is also confidential.

Drazen, whose research (funded by The Metals Company) is looking at mining impacts on the midwater column, says the mining process will discharge mud and chemicals. “There’s a whole suite of potential effects on a completely different ecosystem above the seafloor. We depend upon the water column ecosystem … a lot of animals we like to eat … forage on deep-sea animals,” he says. The discharge of metals and toxins over potentially large areas could contaminate seafood. A recent study suggests that elements in discharge waters could spread further than mining areas, affecting tuna’s food, distribution, and migration corridors. There is increasing evidence that tuna, swordfish, marine mammals and seabirds rely on deep-sea fish, and foraging beaked whales could also be diving down to the seafloor in search of food.

DeepData is experiencing teething problems. A workshop to assess biodiversity for the CCZ in 2019 found inconsistencies in the data, making it difficult to synthesize across the CCZ. Different sampling methods can make it difficult to provide a cohesive picture.

“There’s still a bit of work in progress with DeepData. But certainly, the willingness is there to have it serving people with appropriate needs,” Clark says. “We do still need to be careful of the commercial confidentiality as it relates to the geochemical information in particular.”

The ISA did not respond to requests for comment.

An opaque decision-making body

The structure of the ISA, particularly its de facto decision-making body, the Legal and Technical Commission, is also fraught with transparency challenges. The Legal and Technical Commission assesses mining applications, which currently involve exploration contracts for the deep sea, but all of its meetings are held behind closed doors. The commission is composed of 30 experts nominated by their countries — some by governments that also hold exploration contracts — with only three deep-sea biologists on board.

“Even if some mining companies might genuinely fund what might be considered independent science, we still end up with a problem that the decision about whether or not to mine and the decision around environmental management of seabed mining rests entirely on data that is provided by the mining companies,” says Jaeckel of the University of New South Wales. “There is a lot of trust placed on mining companies.” There is no way to independently verify this data either, because deep-sea science is expensive, she adds. The degree to which companies are accurately reporting the baseline data to the ISA is not clear.

The commission is the only body within the ISA that sees the content of contractor’s applications, so the baseline data that contractors submit to be able to monitor impacts are only visible to the commission. There is an audit of the scientific data by the commission which reviews a contractor’s confidential annual reports. And then there’s public scrutiny of environmental impact assessments by NGOs.

Nauru Ocean Resources Inc., a wholly-owned subsidiary of The Metals Company, is “going to have to produce something really good,” says Clark of the company’s upcoming environmental impact assessment. Clark is a deep-sea biologist who was nominated to sit on the commission by New Zealand, which does not hold an exploration contract with the ISA. “Otherwise, the whole industry’s potential will be affected because it will taint the view of public and NGOs as to what contractors are doing — are they doing a serious and good job at the underlying research or are they trying to cut corners and push the ISA into making hasty decisions?”

In 2017, the commission approved an exploration contract for the Lost City, a metropolis of hydrothermal vents in the Atlantic Ocean that the Convention of Biological Diversity has recognized as an ecologically or biologically significant marine area that should be conserved. Marine scientists issued an open letter to the ISA to turn to independent scientists when evaluating requests for mineral exploration, and some have long called for open meetings and an independent scientific committee to advise the commission. Scientists are now petitioning for a pause on deep-sea exploitation out of concern about impacts on the marine environment.

That baseline research with industry might enable mining is “a very naïve perspective,” adds Smith of the University of Hawai‘i. “My gut feeling is that mining will go forward. It would be really wise to just permit one operation to go forward initially and monitor the heck out of it for 10 years. That would make a lot more sense than permitting multiple operations without even knowing what the real footprint will be in terms of disturbance.”

by DGR News Service | Sep 13, 2021 | Biodiversity & Habitat Destruction, Mining & Drilling

World congress of the International Union for the Conservation of Nature (IUCN) calling for reforms to the International Seabed Authority (ISA).

“Deep seabed mining is an avoidable environmental disaster,” said one expert on global ocean policy.

Featured image: A pair of fish swim near the ocean floor off the coast of Mauritius. A motion calling for an end to deep sea mining of minerals was adopted at the world congress of the International Union for the Conservation of Nature this week. (Photo: Roman Furrer/Flickr/cc)

This article originally appeared in CommonDreams.

By JULIA CONLEY

A vote overwhelmingly in favor of placing a moratorium on deep sea mineral mining at a global biodiversity summit this week has put urgent pressure on the International Seabed Authority to strictly regulate the practice.

The vast majority of governments, NGOs, and civil society groups voted in favor of the moratorium at the world congress of the International Union for the Conservation of Nature (IUCN) on Wednesday, after several conservation groups lobbied in favor of the measure.

“Member countries of the ISA, including France which hosted this Congress, need to wake up and act on behalf of civil society and the environment now, and take action in support of a moratorium.”

—Matthew Gianni, Deep Sea Conservation Coalition

Eighty-one government and government agencies voted for the moratorium, while 18 opposed it and 28, including the United Kingdom, abstained from voting. Among NGOs and other organizations, 577 supported the motion while fewer than three dozen opposed it or abstained.

Deep sea mining for deposits of copper, nickel, lithium, and other metals can lead to the swift loss of entire species that live only on the ocean floor, as well as disturbing ecosystems and food sources and putting marine life at risk for toxic spills and leaks.

Fauna and Flora International, which sponsored the moratorium along with other groups including the Natural Resources Defense Council and Synchronicity Earth, called the vote “a momentous outcome for ocean conservation.”

The motion called for a moratorium on mining for minerals and metals near the ocean floor until environmental impact assessments are completed and stakeholders can ensure the protection of marine life, as well as calling for reforms to the International Seabed Authority (ISA)—the regulatory body made up of 167 nations and the European Union, tasked with overseeing “all mineral-related activities in the international seabed area for the benefit of mankind as a whole.”

In June, a two-year deadline was set for the ISA to begin licensing commercial deep sea mining and to finalize regulations for the industry by 2023.

“Member countries of the ISA, including France which hosted this Congress, need to wake up and act on behalf of civil society and the environment now, and take action in support of a moratorium,” said Matthew Gianni, co-founder of the Deep Sea Conservation Coalition, in a statement.

The World Wide Fund for Nature, another cosponsor of the motion, called on the ISA to reject the deep sea mining industry’s claims that mining for metals on the ocean floor is a partial solution to the climate crisis.

“The pro-deep seabed mining lobby is… selling a story that companies need deep seabed minerals in order to produce electric cars, batteries and other items that reduce carbon emissions,” said Jessica Battle, a senior expert on global ocean policy and governance at the organization. “Deep seabed mining is an avoidable environmental disaster. We can decarbonize through innovation, redesigning, reducing, reusing, and recycling.”

Pippa Howard of Fauna and Flora International wrote ahead of the IUCN summit that “we need to shatter the myth that deep seabed mining is the solution to the climate crisis.”

“Far from being the answer to our dreams, deep seabed mining could well turn out to be the stuff of nightmares,” she wrote. “Deep seabed mining—at least as it is currently conceived—would be an utterly irresponsible and short-sighted idea. In the absence of any suitable mitigation techniques… deep-sea mining should be avoided entirely until that situation changes.”

by DGR News Service | Aug 16, 2021 | Biodiversity & Habitat Destruction, Direct Action, Education, Mining & Drilling, Obstruction & Occupation, Reclamation & Expropriation, Strategy & Analysis, Toxification

A Guide for Resistance

By Carlos Zorrilla with Arden Buck and David Pellow

Resistance to mining is growing worldwide. Although extractive companies are powerful, they are also vulnerable.

About this guide

This guide is intended for leaders and organizers who can work with communities to carry out local actions, and who can also work at the regional, national, and international levels. It describes aspects of the mining process and the dangers your community faces when mining companies seek to operate in your community (Sect. 1), the many strategies you can use to fight back (Sect. 2 and Appendices A and B), examples of successful resistance by communities who fought back (Appendix C), and helpful resources in a companion volume (Supplement). Our hope is that with this guide, you too can succeed in protecting your community against these dangers.

This guide is not only for mining.

Most of the tactics and countermeasures described herein apply equally well to other extractive and exploitative activities: oil, gas, logging, various polluting industries, and large hydroelectric dams. Most activities proposed by large corporations, although they promise benefits, ultimately devastate local communities and their surroundings. If your community is targeted, it is essential to organize and resist. Acknowledgements: The material in this guide draws on the experience of several experts on mining and its impacts, particularly principle author Carlos Zorrilla. The guide came about because he realized that other communities around the world could benefit from the knowledge and experience that he and his colleagues gained while fighting to keep his area from being destroyed by mining companies.

Download the whole guide as PDF here:

Protecting Your Community From Extractive Industries

by DGR News Service | Jul 1, 2021 | Education, Lobbying, Mining & Drilling, Movement Building & Support

This article originally appeared in The Ecologist. Republished under Creative Commons 4.0.

Editor’s note: It’s very important to be clear about the destructiveness of mining and organize resistance against governments and cooperations. While this article is only very cautiously mentioning degrowth, scaling back, and recycling as “solutions”, we believe that societies have to reject and give up industrialism as a whole and immediately start ecological restoration everywhere at emergency speed and scale.

By Diego Francesco Marin

‘Green mining’ is an oxymoron that is gaining traction in the EU and pushes a risky narrative about an environmentally destructive sector.

Mining dominates, exploits and pollutes, suppressing other ways of living with the land. In low-income countries, it can be deadly. Activists, civil society and grassroots movements have been loud and clear about the dangers posed by the mining sector, yet few politicians seem to listen. In the European Union, the European Commission and mining operators are clearly aware of the issues. But unless your community has been targeted as the next mining project to supposedly meet the EU’s climate goals, you are probably not aware of how destructive mining can be.

As part of its Raw Materials Action Plan, the Commission is striving to create the conditions for more mining in Europe by convincing the public that mining can be “green.”

Foolish

Last month, the Portuguese presidency of the EU organised a European conference on so-called green mining in Lisbon. Only one civil society organisation, the EEB, was invited to what had all the appearances of an industry convention rather than a green policy forum.

However, outside the venue, over a hundred activists from grassroots movements and citizens organisations protested the conference and the government-backed lithium mining projects in northern Portugal- despite COVID restrictions.

To gain thesocial license to operate, politicians and industry are challenging previous civil society backlashes against mining projects by equating mining with renewable technologies. Even raising concerns over the toxic fallout of continuous extractivism is deemed foolish.

When communities fight for their right to decide their futures, they are labelled as suffering from a case of nimbyism. Portuguese Secretary of State for Energy, João Galamba even went so far as mentioning that “those who are against mines are against life.”

This scramble to mine is about lucrative business and actually undermines the energy transition. New low-carbon infrastructure needs to be built to enable the move away from fossil fuels, which means money.

Lithium

>Lithium, for example, is one of the most sought-after metals for low-carbon technologies and Europe is almost 100 percent dependent on battery-grade lithium from third countries, especially Chile.

An often-cited figure is that, by 2030, under ‘business as usual’, Europe will need around 18 times more lithium and up to 60 times more by 2050. Therefore, to make the switch to renewable technologies and be competitive, Europe wants to scale up supply to avoid bottlenecks, right in its own backyard.

But this strategy comes with serious concerns. The mountainous Barroso region, for example, sits on Western Europe’s largest lithium deposits but is also located 400 metres from the Covas do Barroso community, in the municipality of Boticas.

Even the Boticas mayor, Fernando Queiroga has spoken openly against the project over pollution, water and environmental worries. He also fears the negative impact it would have on the region’s agricultural, gastronomy and rural tourism sectors.

According to Savannah Resources, the mining operator behind the Minas Do Barroso, the mine would generate €1.3 billion of revenue over its 15-to-20-year lifetime.

Overconsumption

In terms of helping the EU meet its demand, the project would only provide 5 to 6 percent of Europe’s projected lithium requirement in 2030.

A study conducted by the University of Minho for Savannah Resources found that the lithium output of this mine would be “insufficient to meet the demand for lithium derivatives for the production of batteries in Europe”.

This region is one of only seven in Europe to make the Food and Agriculture Organisation’s list of Globally Important Agricultural Heritage Systems. Communities here use “very few surpluses where]the level of consumption of the population is relatively low compared to other regions in the country” as the FAO’s website indicates.

In the age of overconsumption driving the ecological crisis, it is ironic that low-impact communities are targeted for green growth pursuits.

If the Mina do Barroso project is allowed to proceed, the region’s proud agricultural heritage would be undermined and would surely lose its international recognition.

Frenzy

With 30 million additional electric vehicles planned to hit Europe’s roads by 2030, it should come as no surprise that communities on the ground do not want their land to become the next sacrifice zone to feed the EV frenzy.

In Europe, there are three other proposed mining projects where environmental concerns have also been raised, including in Caceres, Spain.

The Iberian Peninsula is a major target for mining companies. In Spain, there are around 2,000 potential licenses for new mining projects. In the case of Portugal, 10 percent of the country’s territory is already under mining concessions.

In the northern Portuguese regions, the situation is troubling amid concerns that open-pit mines may even be allowed near protected areas, as in the case of Serra d’Arga. The Mina do Barroso project is now undergoing public consultation for the environmental impact assessment.

Despite government and industry rhetoric that public participation will be respected, and the needs of local communities will be met, local organisations and activists are not convinced. In January 2021, an NGO submitted an environmental information request to the Portuguese environment ministry, but no access was granted.

Denial

The same request was sent in March to Savannah Resources, but the company also refused.

Although the Commission for Access to Administrative Documents (CADA) issued a report stating that the environmental information that had been requested should be made immediately available, the Portuguese authorities decided to ignore the request.

Only some documents were made available during the public consultations and nearly three weeks after the consultations started.

The lack of access to information kept civil society and local communities in the dark and they lost around 3 precious months.

For the past month, they have had to scrutinise more than 6,000 documents. A formal complaint was submitted in the context of the Aarhus Convention, which protects the right of access to environmental information, over claims of deliberate denial of access to information.

Courts

The case is already before the Portuguese courts and the public prosecutor. The end of the public consultation period for the EIA was to end on June 2nd, the same day of the launch of the Yes to Life, No to Miningjoint position statement to the European Commission, but public pressure over irregularities forced the Portuguese authorities to extend the consultation period to July 16th.

target=”_blank” rel=”noopener”Green mining relates to the belief that we can decouple economic growth from environmental impacts, however, this mindset ignores a larger issue and will ultimately have irreversible consequences on the environment.

Perhaps instead of putting such emphasis on the supply of lithium or other raw materials, we can take a look at the demand. For example, by prioritising circularity over primary resource extraction, we can greatly reduce our need to mine more resources.

Political action to limit global warming is necessary and urgent. This means that we need to find the quickest paths to decarbonisation. But we must do it in less materially intensive ways. We can build cities that are less car-dependent, increase public transport, promote walking or enhance micro e-mobility.

Cycling, for example, is ten times more important than electric cars for reaching net-zero cities. Other solutions include urban mining initiatives that move us toward more circular societies. In an inspiring example from Antwerp, 70 creative makers gather the waste from the city and turn them into a wide variety of products: lamps from old boilers and chairs from paper and sawdust for a whole jazz club.

Solutions

The solutions exist, we just need the political will.

By making the most of the resources we have, European cities can greatly reduce the impact that they create for European rural communities and in low-income countries where most of the mining projects are slated to take place.

However, broader policy measures are also needed. For starters, the EU should agree on creating a headline target to cut its material footprint and continue to promote measures on targeting energy efficiency, recycling, material substitution, use of innovative materials, and the promotion of sustainable lifestyles.

Another way to do this is to look at the energy transition through an environmental justice lens. Granting communities, the right to say no to mining projects by taking inspiration from already enshrined protocols in international law as in the case of Free, Prior and Informed Consent for Indigenous Peoples, the brunt of the energy transition will not have to be put on low-impact communities around the world.

This can address the current imbalance of power between mining companies, governments and communities and the future EU horizontal due diligence law can offer such opportunity. Banning mining projects from taking place within or near protected areas is a necessary step forward.

Living

So can mining ever be green? Maybe that is not the right question. We should instead ask, how do we change the way our societies operate?

How can we create well-being economies? Or perhaps more ambitiously, how do we move away from the need to grow the economy?

Only then can we figure out how much we need to mine. After all, decent living does not have to, and must not, cost us the earth.

This Author– Diego Francesco Marin is a policy officer at the European Environmental Bureau.